Полная версия

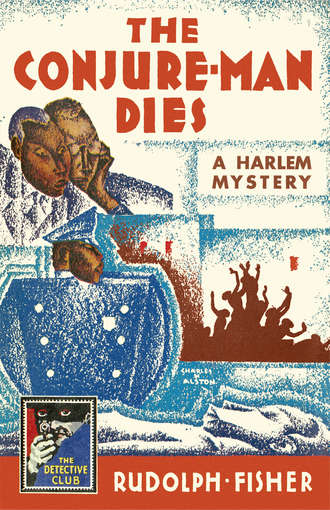

The Conjure-Man Dies: A Harlem Mystery

‘The what?’

‘The D.S.C.—Department of Street Cleaning—but we never called it that, no, suh. Coupla weeks ago I lost that job and couldn’t find me nothin’ else. Then I said to myself, “They’s only one chance, boy—you got to use your head instead o’ your hands.” Well, I figured out the situation like this: The only business what was flourishin’ was monkey-business—’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Monkey-business. Cheatin’—backbitin’, and all like that. Don’t matter how bad business gets, lovin’ still goes on; and long as lovin’ is goin’ on, cheatin’ is goin’ on too. Now folks’ll pay to catch cheaters when they won’t pay for other things, see? So I figure I can hire myself out to catch cheaters as well as anybody—all I got to do is bust in on ’em and tell the judge what I see. See? So I had me them cards printed and I’m r’arin’ to go. But I didn’t know ’twas against the law sho’ ’nough.’

‘Well it is and I may have to arrest you for it.’

Bubber’s dismay was great.

‘Couldn’t you jes’—jes’ tear up the card and let it go at that?’

‘What was your business here tonight?’

‘Me and Jinx come together. We was figurin’ on askin’ the man’s advice about this detective business.’

‘You and who?’

‘Jinx Jenkins—you know—the long boy look like a giraffe you seen downstairs.’

‘What time did you get here?’

‘’Bout half-past ten I guess.’

‘How do you know it was half-past ten?’

‘I didn’t say I knowed it, mistuh. I said I guess. But I know it wasn’t no later’n that.’

‘How do you know?’

Thereupon, Bubber told how he knew.

At eight o’clock sharp, as indicated by his new dollar watch, purchased as a necessary tool of his new profession, he had been walking up and down in front of the Lafayette Theatre, apparently idling away his time, but actually taking this opportunity to hand out his new business cards to numerous theatre-goers. It was his first attempt to get a case and he was not surprised to find that it promptly bore fruit in that happy-go-lucky, care-free, irresponsible atmosphere. A woman to whom he had handed one of his announcements returned to him for further information.

‘I should ’a’ known better,’ he admitted, ‘than to bother with her, because she was bad luck jes’ to look at. She was cross-eyed. But I figure a cross-eyed dollar’ll buy as much as a straight-eyed one and she talked like she meant business. She told me if I would get some good first-class low-down on her big boy, I wouldn’t have no trouble collectin’ my ten dollars. I say “O.K., sister. Show me two bucks in front and his Cleo from behind, and I’ll track ’em down like a bloodhound.” She reached down in her stockin’, I held out my hand and the deal was on. I took her name an’ address an’ she showed me the Cleo and left. That is, I thought she left.

‘The Cleo was the gal in the ticket-box. Oh, mistuh, what a Sheba! Keepin’ my eyes on her was the easiest work I ever did in my life. I asked the flunky out front what this honey’s name was and he tole me Jessie James. That was all I wanted to know. When I looked at her I felt like givin’ the cross-eyed woman back her two bucks.

‘A little before ten o’clock Miss Jessie James turned the ticket-box over to the flunky and disappeared inside. It was too late for me to spend money to go in then, and knowin’ I prob’ly couldn’t follow her everywhere she was goin’ anyhow, I figured I might as well wait for her outside one door as another. So I waited out front, and in three or four minutes out she come. I followed her up the Avenue a piece and round a corner to a private house on 134th Street. After she’d been in a couple o’ minutes I rung the bell. A fat lady come to the door and I asked for Miss Jessie James.

‘“Oh,” she say. “Is you the gentleman she was expectin’?” I say, “Yes ma’am. I’m one of ’em. They’s another one comin’.” She say, “Come right in. You can go up—her room is the top floor back. She jes’ got here herself.” Boy, what a break. I didn’ know for a minute whether this was business or pleasure.

‘When I got to the head o’ the stairs I walked easy. I snook up to the front-room door and found it cracked open ’bout half an inch. Naturally I looked in—that was business. But, friend, what I saw was nobody’s business. Miss Jessie wasn’t gettin’ ready for no ordinary caller. She look like she was gettin’ ready to try on a bathin’ suit and meant to have a perfect fit. Nearly had a fit myself tryin’ to get my breath back. Then I had to grab a armful o’ hall closet, ’cause she reached for a kimono and started for the door. She passed by and I see I’ve got another break. So I seized opportunity by the horns and slipped into her room. Over across one corner was—’

‘Wait a minute,’ interrupted Dart. ‘I didn’t ask for your life history. I only asked—’

‘You ast how I knowed it wasn’t after half-past ten o’clock.’

‘Exactly.’

‘I’m tellin’ you, mistuh. Listen. Over across one corner was a trunk—a wardrobe trunk, standin’ up on end and wide open. I got behind it and squatted down. I looked at my watch. It was ten minutes past ten. No sooner’n I got the trunk straight ’cross the corner again I heard her laughin’ out in the hall and I heard a man laughin’, too. I say to myself, “here ’tis. The bathin’-suit salesman done arrived.”

‘And from behind that trunk, y’see, I couldn’t use nothin’ but my ears—couldn’t see a thing. That corner had me pretty crowded. Well, instead o’ goin’ on and talkin’, they suddenly got very quiet, and natchelly I got very curious. It was my business to know what was goin’ on.

‘So instead o’ scronchin’ down behind the trunk like I’d been doin’, I begun to inch up little at a time till I could see over the top. Lord—what did I do that for? Don’ know jes’ how it happened, but next thing I do know is “wham!”—the trunk had left me. There it was flat on the floor, face down, like a Hindu sayin’ his prayers, and there was me in the corner, lookin’ dumb and sayin’ mine, with the biggest boogy in Harlem ’tween me and the door.

‘Fact is, I forgot I was a detective. Only thing I wanted to detect was the quickest way out. Was that guy evil-lookin’? One thing saved me—the man didn’t know whether to blame me or her. Before he could make up his mind, I shot out o’ that corner past him like a cannon-ball. The gal yelled, “Stop thief!” And the guy started after me. But, shuh!—he never had a chance—even in them runnin’-pants o’ his. I flowed down the stairs and popped out the front door, and who was waitin’ on the sidewalk but the cross-eyed lady. She’d done followed me same as I followed the Sheba. Musta hid when her man went by on the way in. But when he come by chasin’ me on the way out, she jumped in between us and ast him where was his pants.

‘Me, I didn’t stop to hear the answer. I knew it. I made Lenox Avenue in nothin’ and no fifths. That wasn’t no more than quarter past ten. I slowed up and turned down Lenox Avenue. Hadn’ gone a block before I met Jinx Jenkins. I told him ’bout it and ast him what he thought I better do next. Well, somebody’d jes’ been tellin’ him ’bout what a wonderful guy this Frimbo was for folks in need o’ advice. We agreed to come see him and walked on round here. Now, I know it didn’t take me no fifteen minutes to get from that gal’s house here. So I must ’a’ been here before half-past ten, y’see?’

Further questioning elicited that when Jinx and Bubber arrived they had made their way, none too eagerly, up the stairs in obedience to a sign in the lower hallway and had encountered no one until they reached the reception-room in front. Here there had been three men, waiting to see Frimbo. One, Bubber had recognized as Spider Webb, a number-runner who worked for Harlem’s well-known policy-king, Si Brandon. Another, who had pestered Jinx with unwelcome conversation, was a notorious little drug-addict called Doty Hicks. The third was a genial stranger who had talked pleasantly to everybody, revealing himself to be one Easley Jones, a railroad man.

After a short wait, Frimbo’s flunky appeared from the hallway and ushered the railroad man, who had been the first to arrive, out of the room through the wide velvet-curtained passage. While Jones was, presumably, with Frimbo, the two ladies had come in—the young one first. Then Doty Hicks had gone in to Frimbo, then Spider Webb, and finally Jinx. The usher had not himself gone through the wide doorway at any time—he had only bowed the visitors through, turned aside, and disappeared down the hallway.

‘This usher—what was he like?’

‘Tall, skinny, black, stoop-shouldered, and cock-eyed. Wore a long black silk robe like Frimbo’s, but he had a bright yellow sash and a bright yellow thing on his head—you know—what d’y’ call ’em? Look like bandages—’

‘Turban?’

‘That’s it. Turban.’

‘Where is he now?’

‘Don’t ask me, mistuh. I ain’t seen him since he showed Jinx in.’

‘Hm.’

‘Say!’ Bubber had an idea.

‘What?’

‘I bet he done it!’

‘Did what?’

‘Scrambled the man’s eggs!’

‘You mean you think the assistant killed Frimbo?’

‘Sho’!’

‘How do you know Frimbo was killed?’

‘Didn’t—didn’t you and the doc say he was when I was downstairs lookin’ at you?’

‘On the contrary, we said quite definitely that we didn’t know that he was killed, and that even if he was, that blow didn’t kill him.’

‘But—in the front room jes’ now, didn’t the doc tell that lady—’

‘All the doctor said was that it looked like Frimbo had an enemy. Now you say Frimbo was killed and you accuse somebody of doing it.’

‘All I meant—’

‘You were in this house when he died, weren’t you? By your own time.’

‘I was here when the doc says he died, but—’

‘Why would you accuse anybody of a crime if you didn’t know that a crime had been committed?’

‘Listen, mistuh, please. All I meant was, if the man was killed, the flunky might ’a’ done it and hauled hips. He could be in Egypt by now.’

Dart’s identical remark came back to him. He said less sharply:

‘Yes. But on the other hand you might be calling attention to that fact to avert suspicion from yourself.’

‘Who—me?’ Bubber’s eyes went incredibly large. ‘Good Lord, man, I didn’t leave that room yonder—that waitin’-room—till Jinx called me in to see the man—and he was dead then. ’Deed that’s the truth—I come straight up the stairs with Jinx—we went straight in the front room—and I didn’t come out till Jinx called me—ask the others—ask them two women.’

‘I will. But they can only testify for your presence in that room. Who says you came up the stairs and went straight into that room? How can you prove you did that? How do I know you didn’t stop in here by way of that side hall-door there, and attack Frimbo as he sat here in this chair?’

The utter unexpectedness of his own incrimination, and the detective’s startling insistence upon it, almost robbed Bubber of speech, a function which he rarely relinquished. For a moment he could only gape. But he managed to sputter: ‘Judas Priest, mistuh, can’t you take a man’s word for nothin’?’

‘I certainly can’t,’ said the detective.

‘Well, then,’ said Bubber, inspired, ‘ask Jinx. He seen me. He come in with me.’

‘I see. You alibi him and he alibis you. Is that it?’

‘Damn!’ exploded Bubber. ‘You is the most suspicious man I ever met!’

‘You’re not exactly free of suspicion yourself,’ Dart returned dryly.

‘Listen, mistuh. If you bumped a man off, would you run get a doctor and hang around to get pinched? Would you?’

‘If I thought that would make me look innocent I might—yes.’

‘Then you’re dumber’n I am. If I’d done it, I’d been long gone by now.’

‘Still,’ Dart said, ‘you have only the word of your friend Jinx to prove you went straight into the waiting-room. That’s insufficient testimony. Got a handkerchief on you?’

‘Sho’.’ Bubber reached into his breast pocket and produced a large and flagrant affair apparently designed for appearance rather than for service; a veritable flag, crossed in one direction by a bright orange band and in another, at right angles to the first, by a virulent green one. ‘My special kind,’ he said; ‘always buy these. Man has to have a little colour in his clothes, y’see?’

‘Yes, I see. Got any others?’

‘’Nother one like this—but it’s dirty.’ He produced the mate, crumpled and matted, out of another pocket.

‘O.K. Put ’em away. See anybody here tonight with a coloured handkerchief of any kind?’

‘No suh—not that I remember.’

‘All right. Now tell me this. Did you notice the decorations on the walls in the front room when you first arrived?’

‘Couldn’t help noticin’ them things—’nough to scare anybody dizzy.’

‘What did you see?’

‘You mean them false-faces and knives and swords and things?’

‘Yes. Did you notice anything in particular on the mantelpiece?’

‘Yea. I went over and looked at it soon as I come in. What I remember most was a pair o’ clubs. One was on one end o’ the mantelpiece, and the other was on the other. Look like they was made out o’ bones.’

‘You are sure there were two of them?’

‘Sho’ they was two. One on—’

‘Did you touch them?’

‘No suh—couldn’t pay me to touch none o’ them things—might ’a’ been conjured.’

‘Did you see anyone touch them?’

‘No, suh.’

‘You saw no one remove one of them?’

‘No, suh.’

‘So far as you know they are still there?’

‘Yes, suh.’

‘Who was in that room, besides yourself, when you first saw the two clubs?’

‘Everybody. That was befo’ the flunky’d come in to get the railroad man.’

‘I see. Now these two women—how soon after you got there did they come in?’

‘’Bout ten minutes or so.’

‘Did either of them leave the room while you were there?’

‘No, suh.’

‘And the first man—Easley Jones, the railroad porter—he had come into this room before the women arrived?’

‘Yes, suh. He was the first one here, I guess.’

‘After he went in to Frimbo, did he come back into the waiting-room?’

‘No, suh. Reckon he left by this side door here into the hall.’

‘Did either of the other two return to the waiting-room?’

‘No, suh. Guess they all left the same way. Only one that came back was Jinx, when he called me.’

‘And at that time, you and the women were the only people left in the waiting-room?’

‘Yes, suh.’

‘Very good. Could you identify those three men?’

‘’Deed I could. I could even find ’em if you said so.’

‘Perhaps I will. For the present you go back to the front room. Don’t try anything funny—the house is lousy with policemen.’

‘Lousy is right,’ muttered Bubber.

‘What’s that?’

‘I ain’t opened my mouth, mistuh. But listen, you don’t think I done it sho’ ’nough do you?’

‘That will depend entirely on whether the women corroborate your statement.’

‘Well, whatever that is, I sho’ hope they do it.’

CHAPTER VII

‘BRADY, ask the lady who arrived first to come in,’ said Dart, adding in a low aside to the physician, ‘if her story checks with Brown’s on the point of his staying in that room, I think I can use him for something. He couldn’t have taken that club out without leaving the room.’

‘He tells a straight story,’ agreed Dr Archer. ‘Too scared to lie. But isn’t it too soon to let anybody out?’

‘I don’t mean to let him go. But I can send him with a couple o’ cops to identify the other men who were here and bring them back, without being afraid he’ll start anything.’

‘Why not go with him and question them where you find ’em?’

‘It’s easier to have ’em all in one place if possible—saves everybody’s time. Can’t always do it of course. Here comes the lady—your friend.’

‘Be nice to her—she’s the real thing. I’ve known her for years.’

‘O. K.’

Uncertainly, the young woman entered, the beam of light revealing clearly her unusually attractive appearance. With undisguised bewilderment on her pretty face, but with no sign of fear, she took the visitors’ chair.

‘Don’t be afraid, Mrs Crouch. I want you to answer, as accurately as you can, a few questions which may help determine who killed Frimbo.’

‘I’ll be glad to,’ she said in a low, matter-of-fact tone.

‘What time did you arrive here tonight?’

‘Shortly after ten-thirty.’

‘You’re sure of the time?’

‘I was at the Lenox. The feature picture goes on for the last time at ten-thirty. I had seen it already, and when it came on again I left. It is no more than four or five minutes’ walk from there here.’

‘Good. You came directly to Frimbo’s waiting-room?’

‘No. I stopped downstairs to see if my husband was there.’

‘Your husband? Oh—Mr Crouch, the undertaker, is your husband?’

‘Yes. But he was out.’

‘Does he usually go out and leave his place open?’

‘Late in the evening, yes. Up until then there is a clerk. Afterwards if he is called out he just leaves a sign saying when he will return. He never,’ she smiled faintly, ‘has to fear robbers, you see.’

‘But might not calls come in while he is out?’

‘Yes. But they are handled by a telephone exchange. If he doesn’t answer, the exchange takes the call and gives it to him later.’

‘I see. How long did stopping downstairs delay you?’

‘Only a minute. Then I came right up to the waiting-room.’

‘Who was there when you got there?’

‘Four men.’

‘Did you know any of them?’

‘No, but I’d know them if I saw them again.’

‘Describe them.’

‘Well there was a little thin nervous man who looked like he was sick—in fact he was sick, because when he got up to follow the assistant he had a dizzy spell and fell, and all the men jumped to him and had to help him up.’

‘He was the first to go in to Frimbo after you arrived?’

‘Yes. Then there was a heavy-set, rather flashily-dressed man in grey. He went in next. And there were two others who seemed to be together—the two who were in there a few minutes ago when you and Dr Archer came in.’

‘A tall fellow and a short one?’

‘Yes.’

‘About those two—did either of them leave the room while you were there?’

‘The tall one did, when his turn came to see Frimbo.’

‘And the short one?’

‘Well—when the tall one had been out for about five or six minutes, he came back—through the same way that he had gone. It was rather startling because nobody else had come back at all except Frimbo’s man, and he always appeared in the hall doorway, not the other, and always left by the hall doorway also. And, too, this tall fellow looked terribly excited. He beckoned to the short one and they went back together through the passage—into this room.’

‘That was the first and only time the short man left that room while you were there?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you yourself did not leave the room meanwhile?’

‘No. Not until now.’

‘Did anyone else come in?’

‘The other woman, who is in there now.’

‘Very good. Now, pardon me if I seem personal, but it’s my business not to mind my business—to meddle with other people’s. You understand?’

‘Perfectly. Don’t apologize—just ask.’

‘Thank you. Did you know anything about this man Frimbo—his habits, friends, enemies?’

‘No. He had many followers, I know, and a great reputation for being able to cast spells and that sort of thing. His only companion, so far as I know, was his servant. Otherwise he seemed to lead a very secluded life. I imagine he must have been pretty well off financially. He’d been here almost two years. He was always our best tenant.’

‘Tell me why you came to see Frimbo tonight, please.’

‘Certainly. Mr Crouch owns this house, among others, and Frimbo is our tenant. My job is collecting rents, and tonight I came to collect Frimbo’s.’

‘I see. But do you find it more convenient to see tenants at night?’

‘Not so much for me as for them. Most of them are working during the day. And Frimbo simply can’t be seen in the daytime—he won’t see anyone either professionally or on business until after dark. It’s one of his peculiarities, I suppose.’

‘So that by coming during his office hours you are sure of finding him available?’

‘Exactly.’

‘All right, Mrs Crouch. That’s all for the present. Will you return to the front room? I’d let you go at once, but you may be able to help me further if you will.’

‘I’ll be glad to.’

‘Thank you. Brady, call in Bubber Brown and one of those extra men.’

When Bubber reappeared, Dart said:

‘You told me you could locate and identify the three men who preceded Jenkins?’

‘Yes, suh. I sho’ can.’

‘How?’

‘Well, I been seein’ that little Doty Hicks plenty. He hangs out ’round his brother’s night club. ’Cose ev’ybody knows Spider Webb’s a runner and I can find him from now till mornin’ at Patmore’s Pool Room. And that other one, the railroad man, he and I had quite a conversation before he come in to see Frimbo, and I found out where he rooms when he’s in town. Jes’ a half a block up the street here, in a private house.’

‘Good.’ The detective turned to the officer whom Brady had summoned:

‘Hello, Hanks. Listen Hanks, you take Mr Brown there around by the precinct, pick up another man, and then go with Mr Brown and bring the men he identifies here. There’ll be three of ’em. Take my car and make it snappy.’

Jinx, behind a mask of scowling ill-humour, which was always his readiest defence under strain, sat now in the uncomfortably illuminated chair and growled his answers into the darkness whence issued Dart’s voice. This apparently crusty attitude, which long use had made habitual, served only to antagonize his questioner, so that even the simplest of his answers were taken as unsatisfactory. Even in the perfectly routine but obviously important item of establishing his identity, he made a bad beginning.

‘Have you anything with you to prove your identity?’

‘Nothin’ but my tongue.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean I say I’m who I is. Who’d know better?’

‘No one, of course. But it’s possible that you might say who you were not.’

‘Who I ain’t? Sho’ I can say who I ain’t. I ain’t Marcus Garvey, I ain’t Al Capone, I ain’t Cal Coolidge—I ain’t nobody but me—Jinx Jenkins, myself.’

‘Very well, Mr Jenkins. Where do you live? What sort of work do you do?’

‘Any sort I can get. Ain’t doin’ nothin’ right now.’

‘M-m. What time did you get here tonight?’

On this and other similar points, Jinx’s answers, for all their gruffness, checked with those of Bubber and Martha Crouch. He had come with Bubber a little before ten-thirty. They had gone straight to the waiting-room and found three men. The women had come in later. Then the detective asked him to describe in detail what had transpired when he left the others and went in to see Frimbo. And though Jinx’s vocabulary was wholly inadequate, so deeply had that period registered itself upon his mind that he omitted not a single essential item. His imperfections of speech became negligible and were quite ignored; indeed, the more tutored minds of his listeners filled in or substituted automatically, and both the detective and the physician, the latter perhaps more completely, were able to observe the reconstructed scene as if it were even now being played before their eyes.

The black servitor with the yellow headdress and the cast in one eye ushered Jinx to the broad black curtains, saying in a low voice as he bowed him through, ‘Please go in, sit down, say nothing till Frimbo speaks.’ Thereupon the curtains fell to behind him and he was in a small dark passage, whose purpose was obviously to separate the waiting-room from the mystic chamber beyond and thus prevent Frimbo’s voice from reaching the circle of waiting callers. Jinx shuffled forward toward the single bright light that at once attracted and blinded. He sidled in between the chair and table and sat down facing the figure beneath the hanging light. He was unable, because of the blinding glare, to descry any characteristic feature of the man he had come to see; he could only make out a dark shadow with a head that seemed to be enormous, cocked somewhat sidewise as if in a steady contemplation of the visitor.