Полная версия

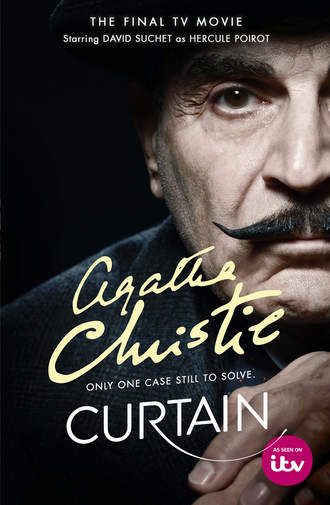

Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case

Agatha Christie

Curtain: Poirot’s

Last Case

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1975

Copyright © 1975 Agatha Christie Ltd.

All rights reserved.

Agatha Christie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

www.agathachristie.com

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007527601

Ebook Edition 2010 ISBN: 9780007422241

Version: 2018-08-14

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Postscript

Keep Reading

About Agatha Christie

The Agatha Christie Collection

E-Book Extras

The Poirots

Essay by Charles Osborne

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

I

Who is there who has not felt a sudden startled pang at reliving an old experience, or feeling an old emotion?

‘I have done this before . . .’

Why do those words always move one so profoundly?

That was the question I asked myself as I sat in the train watching the flat Essex landscape outside.

How long ago was it that I had taken this selfsame journey? Had felt (ridiculously) that the best of life was over for me! Wounded in that war that for me would always be the war – the war that was wiped out now by a second and a more desperate war.

It had seemed in 1916 to young Arthur Hastings that he was already old and mature. How little had I realized that, for me, life was only then beginning.

I had been journeying, though I did not know it, to meet the man whose influence over me was to shape and mould my life. Actually, I had been going to stay with my old friend, John Cavendish, whose mother, recently remarried, had a country house named Styles. A pleasant renewing of old acquaintanceships, that was all I had thought it, not foreseeing that I was shortly to plunge into all the dark embroilments of a mysterious murder.

It was at Styles that I had met again that strange little man, Hercule Poirot, whom I had first come across in Belgium.

How well I remembered my amazement when I had seen the limping figure with the large moustache coming up the village street.

Hercule Poirot! Since those days he had been my dearest friend, his influence had moulded my life. In company with him, in the hunting down of yet another murderer, I had met my wife, the truest and sweetest companion any man could have had.

She lay now in Argentine soil, having died as she would have wished, with no long drawn out suffering, or feebleness of old age. But she had left a very lonely and unhappy man behind her.

Ah! If I could go back – live life all over again. If this could have been that day in 1916 when I first travelled to Styles . . . What changes had taken place since then! What gaps amongst the familiar faces! Styles itself had been sold by the Cavendishes. John Cavendish was dead, though his wife, Mary (that fascinating enigmatical creature), was still alive, living in Devonshire. Laurence was living with his wife and children in South Africa. Changes – changes everywhere.

But one thing, strangely enough, was the same. I was going to Styles to meet Hercule Poirot.

How stupefied I had been to receive his letter, with its heading Styles Court, Styles, Essex.

I had not seen my old friend for nearly a year. The last time I had seen him I had been shocked and saddened. He was now a very old man, and almost crippled with arthritis. He had gone to Egypt in the hopes of improving his health, but had returned, so his letter told me, rather worse than better. Nevertheless, he wrote cheerfully . . .

II

And does it not intrigue you, my friend, to see the address from which I write? It recalls old memories, does it not? Yes, I am here, at Styles. Figure to yourself, it is now what they call a guest house. Run by one of your so British old Colonels – very ‘old school tie’ and ‘Poona’. It is his wife, bien entendu, who makes it pay. She is a good manager, that one, but the tongue like vinegar, and the poor Colonel, he suffers much from it. If it were me I would take a hatchet to her!

I saw their advertisement in the paper, and the fancy took me to go once again to the place which first was my home in this country. At my age one enjoys reliving the past.

Then figure to yourself, I find here a gentleman, a baronet who is a friend of the employer of your daughter. (That phrase it sounds a little like the French exercise, does it not?)

Immediately I conceive a plan. He wishes to induce the Franklins to come here for the summer. I in my turn will persuade you and we shall be all together, en famille. It will be most agreeable. Therefore, mon cher Hastings, dépêchez-vous, arrive with the utmost celerity. I have commanded for you a room with bath (it is modernized now, you comprehend, the dear old Styles) and disputed the price with Mrs Colonel Luttrell until I have made an arrangement très bon marché.

The Franklins and your charming Judith have been here for some days. It is all arranged, so make no histories.

A bientôt, Yours always, Hercule Poirot

The prospect was alluring, and I fell in with my old friend’s wishes without demur. I had no ties and no settled home. Of my children, one boy was in the Navy, the other married and running the ranch in the Argentine. My daughter Grace was married to a soldier and was at present in India. My remaining child, Judith, was the one whom secretly I had always loved best, although I had never for one moment understood her. A queer, dark, secretive child, with a passion for keeping her own counsel, which had sometimes affronted and distressed me. My wife had been more understanding. It was, she assured me, no lack of trust or confidence on Judith’s part, but a kind of fierce compulsion. But she, like myself, was sometimes worried about the child. Judith’s feelings, she said, were too intense, too concentrated, and her instinctive reserve deprived her of any safety valve. She had queer fits of brooding silence and a fierce, almost bitter power of partisanship. Her brains were the best of the family and we gladly fell in with her wish for a university education. She had taken her B.Sc. about a year ago, and had then taken the post of secretary to a doctor who was engaged in research work connected with tropical disease. His wife was somewhat of an invalid.

I had occasionally had qualms as to whether Judith’s absorption in her work, and devotion to her employer, were not signs that she might be losing her heart, but the business-like footing of their relationship assured me.

Judith was, I believed, fond of me, but she was very undemonstrative by nature, and she was often scornful and impatient of what she called my sentimental and outworn ideas. I was, frankly, a little nervous of my daughter!

At this point my meditations were interrupted by the train drawing up at the station of Styles St Mary. That at least had not changed. Time had passed it by. It was still perched up in the midst of fields, with apparently no reason for existence.

As my taxi passed through the village, though, I realized the passage of years. Styles St Mary was altered out of all recognition. Petrol stations, a cinema, two more inns and rows of council houses.

Presently we turned in at the gate of Styles. Here we seemed to recede again from modern times. The park was much as I remembered it, but the drive was badly kept and much overgrown with weeds growing up over the gravel. We turned a corner and came in view of the house. It was unaltered from the outside and badly needed a coat of paint.

As on my arrival all those years ago, there was a woman’s figure stooping over one of the garden beds. My heart missed a beat. Then the figure straightened up and came towards me, and I laughed at myself. No greater contrast to the robust Evelyn Howard could have been imagined.

This was a frail elderly lady, with an abundance of curly white hair, pink cheeks, and a pair of cold pale blue eyes that were widely at variance with the easy geniality of her manner, which was frankly a shade too gushing for my taste.

‘It’ll be Captain Hastings now, won’t it?’ she demanded. ‘And me with my hands all over dirt and not able to shake hands. We’re delighted to see you here – the amount we’ve heard about you! I must introduce myself. I’m Mrs Luttrell. My husband and I bought this place in a fit of madness and have been trying to make a paying concern of it. I never thought the day would come when I’d be a hotel keeper! But I’ll warn you, Captain Hastings, I’m a very business-like woman. I pile up the extras all I know how.’

We both laughed as though at an excellent joke, but it occurred to me that what Mrs Luttrell had just said was in all probability the literal truth. Behind the veneer of her charming old lady manner, I caught a glimpse of flint-like hardness.

Although Mrs Luttrell occasionally affected a faint brogue, she had no Irish blood. It was a mere affectation.

I enquired after my friend.

‘Ah, poor little M. Poirot. The way he’s been looking forward to your coming. It would melt a heart of stone. Terribly sorry I am for him, suffering the way he does.’

We were walking towards the house and she was peeling off her gardening gloves.

‘And your pretty daughter, too,’ she went on. ‘What a lovely girl she is. We all admire her tremendously. But I’m old-fashioned, you know, and it seems to me a shame and a sin that a girl like that, that ought to be going to parties and dancing with young men, should spend her time cutting up rabbits and bending over a microscope all day. Leave that sort of thing to the frumps, I say.’

‘Where is Judith?’ I asked. ‘Is she somewhere about?’

Mrs Luttrell made what children call ‘a face’.

‘Ah, the poor girl. She’s cooped up in that studio place down at the bottom of the garden. Dr Franklin rents it from me and he’s had it all fitted up. Hutches of guinea pigs he’s got there, the poor creatures, and mice and rabbits. I’m not sure that I like all this science, Captain Hastings. Ah, here’s my husband.’

Colonel Luttrell had just come round the corner of the house. He was a very tall, attenuated old man, with a cadaverous face, mild blue eyes and a habit of irresolutely tugging at his little white moustache.

He had a vague, rather nervous manner.

‘Ah, George, here’s Captain Hastings arrived.’

Colonel Luttrell shook hands. ‘You came by the five – er – forty, eh?’

‘What else should he have come by?’ said Mrs Luttrell sharply. ‘And what does it matter anyway? Take him up and show him his room, George. And then maybe he’d like to go straight to M. Poirot – or would you rather have tea first?’

I assured her that I did not want tea and would prefer to go and greet my friend.

Colonel Luttrell said, ‘Right. Come along. I expect – er – they’ll have taken your things up already – eh, Daisy?’

Mrs Luttrell said tartly, ‘That’s your business, George. I’ve been gardening. I can’t see to everything.’

‘No, no, of course not. I – I’ll see to it, my dear.’

I followed him up the front steps. In the doorway we encountered a grey-haired man, slightly built, who was hurrying out with a pair of field-glasses. He limped, and had a boyish eager face. He said, stammering slightly: ‘There’s a pair of n-nesting blackcaps down by the sycamore.’

As we went into the hall, Luttrell said, ‘That’s Norton. Nice fellow. Crazy about birds.’

In the hall itself, a very big man was standing by the table. He had obviously just finished telephoning. Looking up he said, ‘I’d like to hang, draw and quarter all contractors and builders. Never get anything done right, curse ’em.’

His wrath was so comical and so rueful, that we both laughed. I felt very attracted at once towards the man. He was very good-looking, though a man well over fifty, with a deeply tanned face. He looked as though he had led an out-of-doors life, and he looked, too, the type of man that is becoming more and more rare, an Englishman of the old school, straightforward, fond of out-of-doors life, and the kind of man who can command.

I was hardly surprised when Colonel Luttrell introduced him as Sir William Boyd Carrington. He had been, I knew, Governor of a province in India, where he had been a signal success. He was also renowned as a first-class shot and big game hunter. The sort of man, I reflected sadly, that we no longer seemed to breed in these degenerate days.

‘Aha,’ he said. ‘I’m glad to meet in the flesh that famous personage mon ami Hastings.’ He laughed. ‘The dear old Belgian fellow talks about you a lot, you know. And then, of course, we’ve got your daughter here. She’s a fine girl.’

‘I don’t suppose Judith talks about me much,’ I said, smiling.

‘No, no, far too modern. These girls nowadays always seem embarrassed at having to admit to a father or mother at all.’

‘Parents,’ I said, ‘are practically a disgrace.’

He laughed. ‘Oh, well – I don’t suffer that way. I’ve no children, worse luck. Your Judith is a very good-looking wench, but terribly high-brow. I find it rather alarming.’ He picked up the telephone receiver again. ‘Hope you don’t mind, Luttrell, if I start damning your exchange to hell. I’m not a patient man.’

‘Do ’em good,’ said Luttrell.

He led the way upstairs and I followed him. He took me along the left wing of the house to a door at the end, and I realized that Poirot had chosen for me the room I had occupied before.

There were changes here. As I walked along the corridor some of the doors were open and I saw that the old-fashioned large bedrooms had been partitioned off so as to make several smaller ones.

My own room, which had not been large, was unaltered save for the installation of hot and cold water, and part of it had been partitioned off to make a small bathroom. It was furnished in a cheap modern style which rather disappointed me. I should have preferred a style more nearly approximating to the architecture of the house itself.

My luggage was in my room and the Colonel explained that Poirot’s room was exactly opposite. He was about to take me there when a sharp cry of ‘George’ echoed up from the hall below.

Colonel Luttrell started like a nervous horse. His hand went to his lips.

‘I – I – sure you’re all right? Ring for what you want –’

‘George.’

‘Coming, my dear, coming.’

He hurried off down the corridor. I stood for a moment looking after him. Then, with my heart beating slightly faster, I crossed the corridor and rapped on the door of Poirot’s room.

Chapter 2

Nothing is so sad, in my opinion, as the devastation wrought by age.

My poor friend. I have described him many times. Now to convey to you the difference. Crippled with arthritis, he propelled himself about in a wheeled chair. His once plump frame had fallen in. He was a thin little man now. His face was lined and wrinkled. His moustache and hair, it is true, were still of a jet black colour, but candidly, though I would not for the world have hurt his feelings by saying so to him, this was a mistake. There comes a moment when hair dye is only too painfully obvious. There had been a time when I had been surprised to learn that the blackness of Poirot’s hair came out of a bottle. But now the theatricality was apparent and merely created the impression that he wore a wig and had adorned his upper lip to amuse the children!

Only his eyes were the same as ever, shrewd and twinkling, and now – yes, undoubtedly – softened with emotion.

‘Ah, mon ami Hastings – mon ami Hastings . . .’

I bent my head and, as was his custom, he embraced me warmly.

‘Mon ami Hastings!’

He leaned back, surveying me with his head a little to one side.

‘Yes, just the same – the straight back, the broad shoulders, the grey of the hair – très distingué. You know, my friend, you have worn well. Les femmes, they still take an interest in you? Yes?’

‘Really, Poirot,’ I protested. ‘Must you –’

‘But I assure you, my friend, it is a test – it is the test. When the very young girls come and talk to you kindly, oh so kindly – it is the end! “The poor old man,” they say, “we must be nice to him. It must be so awful to be like that.” But you, Hastings – vous êtes encore jeune. For you there are still possibilities. That is right, twist your moustache, hunch your shoulders – I see it is as I say – you would not look so self-conscious otherwise.’

I burst out laughing. ‘You really are the limit, Poirot. And how are you yourself ?’

‘Me,’ said Poirot with a grimace. ‘I am a wreck. I am a ruin. I cannot walk. I am crippled and twisted. Mercifully I can still feed myself, but otherwise I have to be attended to like a baby. Put to bed, washed and dressed. Enfin, it is not amusing that. Mercifully, though the outside decays, the core is still sound.’

‘Yes, indeed. The best heart in the world.’

‘The heart? Perhaps. I was not referring to the heart. The brain, mon cher, is what I mean by the core. My brain, it still functions magnificently.’

I could at least perceive clearly that no deterioration of the brain in the direction of modesty had taken place.

‘And you like it here?’ I asked.

Poirot shrugged his shoulders. ‘It suffices. It is not, you comprehend, the Ritz. No, indeed. The room I was in when I first came here was both small and inadequately furnished. I moved to this one with no increase of price. Then, the cooking, it is English at its worst. Those Brussels sprouts so enormous, so hard, that the English like so much. The potatoes boiled and either hard or falling to pieces. The vegetables that taste of water, water, and again water. The complete absence of the salt and pepper in any dish –’ he paused expressively.

‘It sounds terrible,’ I said.

‘I do not complain,’ said Poirot, and proceeded to do so. ‘And there is also the modernization, so called. The bathrooms, the taps everywhere and what comes out of them? Lukewarm water, mon ami, at most hours of the day. And the towels, so thin, so meagre!’

‘There is something to be said for the old days,’ I said thoughtfully. I remembered the clouds of steam which had gushed from the hot tap of the one bathroom Styles had originally possessed, one of those bathrooms in which an immense bath with mahogany sides had reposed proudly in the middle of the bathroom floor. Remembered, too, the immense bath towels, and the frequent shining brass cans of boiling hot water that stood in one’s old-fashioned basin.

‘But one must not complain,’ said Poirot again. ‘I am content to suffer – for a good cause.’

A sudden thought struck me.

‘I say, Poirot, you’re not – er – hard up, are you? I know the war hit investments very badly –’

Poirot reassured me quickly.

‘No, no, my friend. I am in most comfortable circumstances. Indeed, I am rich. It is not the economy that brings me here.’

‘Then that’s all right,’ I said. I went on: ‘I think I can understand your feeling. As one gets on, one tends more and more to revert to the old days. One tries to recapture old emotions. I find it painful to be here, in a way, and yet it brings back to me a hundred old thoughts and emotions that I’d quite forgotten I ever felt. I dare say you feel the same.’

‘Not in the least. I do not feel like that at all.’

‘They were good days,’ I said sadly.

‘You may speak for yourself, Hastings. For me, my arrival at Styles St Mary was a sad and painful time. I was a refugee, wounded, exiled from home and country, existing by charity in a foreign land. No, it was not gay. I did not know then that England would come to be my home and that I should find happiness here.’

‘I had forgotten that,’ I admitted.

‘Precisely. You attribute always to others the sentiments that you yourself experience. Hastings was happy – everybody was happy!’

‘No, no,’ I protested, laughing.

‘And in any case it is not true,’ continued Poirot. ‘You look back, you say, the tears rising in your eyes, “Oh, the happy days. Then I was young.” But indeed, my friend, you were not so happy as you think. You had recently been severely wounded, you were fretting at being no longer fit for active service, you had just been depressed beyond words by your sojourn in a dreary convalescent home and, as far as I remember, you proceeded to complicate matters by falling in love with two women at the same time.’

I laughed and flushed.

‘What a memory you have, Poirot.’

‘Ta ta ta – I remember now the melancholy sigh you heaved as you murmured fatuities about two lovely women.’

‘Do you remember what you said? You said, “And neither of them for you! But courage, mon ami. We may hunt together again and then perhaps –”’

I stopped. For Poirot and I had gone hunting again to France and it was there that I had met the one woman . . .

Gently my friend patted my arm.

‘I know, Hastings, I know. The wound is still fresh. But do not dwell on it, do not look back. Instead look forward.’

I made a gesture of disgust.

‘Look forward? What is there to look forward to?’

‘Eh bien, my friend, there is work to be done.’

‘Work? Where?’

‘Here.’

I stared at him.

‘Just now,’ said Poirot, ‘you asked me why I had come here. You may not have observed that I gave you no answer. I will give the answer now. I am here to hunt down a murderer.’

I stared at him with even more astonishment. For a moment I thought he was rambling.

‘You really mean that?’

‘But certainly I mean it. For what other reason did I urge you to join me? My limbs, they are no longer active, but my brain, as I told you, is unimpaired. My rule, remember, has been always the same – sit back and think. That I still can do – in fact it is the only thing possible for me. For the more active side of the campaign I shall have with me my invaluable Hastings.’