Полная версия

Ripper

Amanda rushed over, her heart pounding. Inside the van were three boys wreathed in clouds of smoke, all high as kites, including the driver. One of them got out of the passenger seat and gestured for her to sit next to the driver, a young guy with black hair who was very handsome in a Goth sort of way. “Hey, I’m Clive, Cynthia’s brother,” he introduced himself, flooring the accelerator before Amanda even had time to close the door. Amanda recalled that Cynthia had introduced them at the school Christmas concert. Clive had shown up with his parents, wearing a blue suit, white shirt, and patent leather shoes, a very different look from this guy sitting next to her with his deathly pale complexion and bags under his eyes that looked like bruises. After the school concert Clive, with mocking, overstated formality, had congratulated her on her violin solo. “See you soon, I hope,” he said, winking, as he left. Amanda was sure that she had misheard; as far as she was aware, until that moment no boy had ever looked at her twice. She decided that this must have something to do with Cynthia’s unexpected invitation. This new, ghostly version of Clive, to say nothing of his erratic driving, worried her somewhat, but at least he was someone she knew, someone she could ask to drop her off tomorrow at school in time.

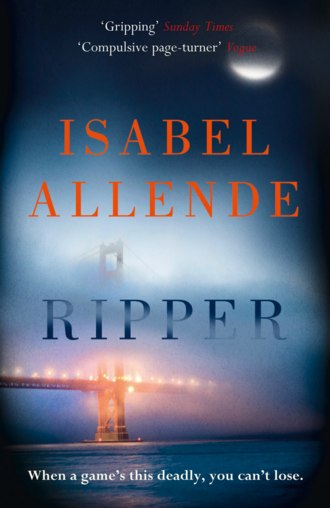

Clive drove on, letting out eerie howls and drinking from a hip flask the boys were passing around, but he managed to find the Golden Gate Bridge and get onto Route 101 without crashing the car or attracting the attention of the police. In Sausalito, Cynthia and another girl climbed into the van, settled into their seats, and immediately joined in the drinking without so much as glancing at Amanda or acknowledging her greeting. With a peremptory gesture, Clive passed the hip flask to Amanda, who didn’t dare refuse. Hoping it might relax her a little, she took a sip that left her throat on fire and her eyes welling with tears; she felt foolish and out of place, as she often did when she was in a group. Worse still, she felt ridiculous, as neither of the girls had dressed up like she had. It was too late now to try and cover up her paint-streaked forearms, since she’d put her grandfather’s cardigan into her backpack before getting into the van. She tried to ignore the sarcastic whispers from the backseat. Clive took the exit at Tiburon Boulevard and drove down the long road that hugged the shore of Richardson Bay, then turned up a hill and glanced around, trying to get his bearings. When they finally arrived at their destination, Amanda saw that it was a private residence shielded from the neighboring houses by a high, seemingly impenetrable wall. Dozens of cars and motorbikes were parked out on the street. She climbed out of the van, knees trembling, and followed Clive through a dark garden. At the foot of the steps leading up to the house, she hid her backpack under a bush, but she clung to her cell phone like a life raft.

Inside were throngs of teenagers, some dancing to the deafening thump of the music, others drinking, and a few sprawled on the stairs amid bottles and beer cans. There were no lasers, no psychedelic colors, just a deserted house stripped of furniture, with a few packing cases in the living room; the air was thick with smoke, and there was a rancid stench, a mixture of paint, dope, and garbage. Amanda froze, unable to move, but Clive hugged her to his body and began to twitch to the frenetic rhythm of the music, dragging her into the living room, where everyone was dancing alone, each lost in a private little world. Someone handed her a paper cup of rum and pineapple juice, and her mouth felt so dry she drained it in three gulps. She felt herself choke with fear and claustrophobia, something that used to happen to her when, as a little girl, she would hide in her makeshift tent to escape the terrible perils of the world, the crushing presence of human beings, their oppressive odors and booming voices.

Clive kissed her neck, searching for her lips, and she responded with a smack from her cell phone that almost broke his nose but did little to discourage him. Desperate, she extricated herself from the hands slipping into the neckline of her T-shirt and up her short skirt, trying to elbow her way out. Amanda tolerated physical contact only from her immediate family and some animals; finding herself being mauled, invaded, hemmed in by other bodies, she began to howl, but the blaring music drowned out her screams. She felt as though she were at the bottom of the sea, with no air, no voice, slowly drowning.

Amanda, who usually prided herself on knowing the time without needing a watch, had no idea how long she’d spent in the house. She didn’t know whether she’d seen Cynthia and Clive again that night, or how she had managed to force her way through the crowd to hide among the packing cases on which music equipment had been set up. For what seemed an eternity, she stayed huddled inside one of the crates, doubled up like an acrobat and trembling uncontrollably, her eyes tight shut, her hands clasped over her ears. It did not occur to her to run into the street, to call her grandfather or phone her parents.

At some point the police arrived in a deafening wail of sirens, surrounded the property, and burst in, but by then Amanda was in such a state that it was twenty minutes before she realized that the chatter of teenagers and the thump of music had been replaced by the sound of orders, by whistles and screams. She steeled herself, opening her eyes and peering between the planks of her hiding place to see flashlight beams and the legs of people being rounded up by uniformed officers. A few kids tried to make a run for it, but most meekly obeyed the order to go out and line up in the street, where they were frisked for weapons and drugs and questioned, those underage being separated from the rest. They all gave the same story—they had received an invitation from a friend by SMS or on Facebook, and did not know whose house it was, or that it was unoccupied and currently up for sale, nor could they explain how they had entered the premises.

Amanda remained deathly silent inside her shelter, and no one thought to look among the crates, though two or three officers searched the rest of the house from top to bottom, opening doors and checking alcoves to make sure there were no stragglers. Gradually the interior of the house became calm, the silence broken only by the muffled sound of voices from the street, and Amanda was able to think clearly. In the silence, without the menacing presence of the partygoers, she felt the walls retreating, and she could breathe again. She had decided to wait until everyone had left before she emerged from her hiding place when suddenly she heard an officer’s commanding voice giving orders that the house be locked and guarded until a technician could come to reset the alarm system.

An hour and a half later, the police had arrested all the intoxicated kids, taken details of the others and let them go, and ferried those who were underage down to the station to wait for their parents. Someone from the security company bolted the windows and doors and turned on the alarm and motion sensors. Locked up in this dark abandoned mansion where the sickening stench of the party still lingered, Amanda was unable to move or even open a window without triggering the alarm. After the arrival of the police, she’d felt that there was no way out; she could hardly ask her mother, who did not have a car, to come pick her up; her father would have been humiliated in front of his colleagues through his daughter’s stupidity; and she certainly could not call her grandfather, who would never forgive her for going to such a place without telling him. She could think of only one person who would help her without asking questions. She rang the number until her battery was dead, but every time she reached voice mail. Come and get me, come and get me. Shivering with cold, she curled up in the packing case once more and waited for dawn, praying that someone would come to let her out.

Sometime between two and three in the morning, Ryan’s cell phone vibrated several times. It was far from his bed, plugged in to charge. It was bitterly cold in the loft, a vast, sparsely furnished open-plan apartment in a former printworks with exposed brick walls, cement floors, and a tangle of aluminum pipes running across the ceiling, with no curtains, no carpets, and no heating. Ryan slept in his boxer shorts, covered with an electric blanket, a pillow over his head. At 5:00 a.m., Attila, who found the winter nights too long, jumped up on the bed to let him know that it was time to begin his morning rituals.

Ryan sat bolt upright, acting on military instinct, his head still swimming with images from a disturbing dream. In the darkness, he groped on the floor for his prosthetic leg and strapped it on. Attila was nudging him with his snout, and Ryan responded to this greeting by patting the dog’s back once or twice; then he flicked on the light, pulled on sweatpants and thick socks, and padded to the bathroom. Emerging again, he found Attila waiting with feigned indifference, betrayed by his irrepressibly wagging tail. The routine was the same every morning. “I’m coming, fella,” said Ryan, drying his face with a towel. “Just hold on a second.” He began measuring out food into the dog’s bowl, at which point Attila, abandoning all pretense, began the complicated little dance with which he always greeted breakfast, though he did not approach the bowl until Ryan gave him the signal.

Before beginning the slow Qigong exercises, his daily half hour of meditation in movement, Ryan glanced at his cell, at which point he noticed that he had a long list of missed calls from Amanda. Please come get me, I’m hiding, don’t say anything to Mom, please come get me. . . . He dialed and dialed her number, and when he could not get through, he felt his heart lurch in his chest before his habitual calm kicked in again, the calmness learned as part of the toughest military training anywhere in the world. Indiana’s daughter was in trouble, he realized, but it was not serious: she had not been kidnapped, nor did she seem to be in any real danger, though she had to be very scared, given that she seemed unable to explain what was happening or where exactly she was.

He dressed in a matter of seconds and sat down in front of his computers. He had systems and software as sophisticated as any used by the Pentagon, making it possible for him to work remotely. Triangulating the location of a cell phone that had rung him eighteen times was easy. He called the station house in Tiburon, rattled off his CIA badge number, requested he be put through to the chief, and asked whether there had been any callouts during the night. The officer, assuming Ryan was concerned about one of the teenagers who had been arrested, told him about the rave, mentioning the address but downplaying the incident—this was not the first time something like this had happened, and there had been no vandalism. Everything was fine now, he said; the alarm had been switched on, and they had been in touch with the real estate agents selling the property so they could send round a cleaning crew. In all probability, charges would not be brought against the kids, but that decision was not a police matter. Ryan thanked him, and a moment later he had an aerial view of the property on his computer screen and a map of how to get there. “C’mon, Attila!” he called, and though the dog could not hear, he knew from Ryan’s manner that they weren’t going for a walk around the block: this was a call to action.

As he raced down to his truck, Ryan phoned Pedro Alarcón, who at this hour was probably preparing for class and sipping maté. His friend still clung to old habits from his native Uruguay, such as drinking this bitter greenish concoction, which Ryan personally thought tasted foul. He was punctilious about the ritual: he would only use the maté gourd and the silver straw he had inherited from his parents, yerba imported directly from Montevideo, and filtered water heated to a precise temperature.

“Get some clothes on—I’ll be there to pick you up in eleven minutes,” Ryan said by way of greeting, “and bring whatever you need to disable an alarm.”

“It’s early, man. . . . What’s the deal?”

“Unlawful entry.”

“What kind of an alarm system?”

“It’s a private house, shouldn’t be too complicated.”

Pedro sighed. “At least we’re not robbing a bank.”

It was still dark, and Monday-morning rush hour had not yet started when Ryan, Pedro, and Attila crossed the Golden Gate Bridge. Yellowish floodlights lit the red steel structure, which looked as though it were suspended in midair, and from the distance came the wail of the lighthouse siren that guided vessels safely through the dense fog. By the time they reached the house in Tiburon, the sky was beginning to pale, a few stray cars were circulating, and the early-morning joggers were just setting out.

Assuming that the residents of such an elegant neighborhood would be suspicious of strangers, the Navy SEAL parked his truck a block from the house and pretended to be walking his dog while he reconnoitered the terrain.

Pedro Alarcón walked briskly toward the house as though he had been sent by the owner, slipped a picklock into the padlock securing the gate—child’s play to this Houdini who could crack a safe with his eyes closed—and in less than a minute had it open. Security was Ryan’s area of expertise; he worked with military and governmental agencies who hired him to protect their information. His job was to get inside the head of the person who might want to steal such data—think like the enemy, imagine all the possible ways of gaining access—and then design a system to prevent it from happening. Watching Alarcón at work with his picklock, it occurred to Ryan that one man, with the necessary skills and determination, could break even the most sophisticated security codes. This was the danger of terrorism: it pitted the cunning of a single individual hiding in a crowd against the colossal might of the most powerful nations on earth.

Now fifty-nine, Pedro Alarcón had been forced to leave Uruguay during the bloody dictatorship in 1976. At eighteen he had joined the tupamaros, an urban Communist guerrilla organization waging an armed struggle against the government, convinced that only by violence could they change Uruguay’s prevailing regime of abuse, corruption, and injustice. The tupamaros planted bombs, robbed banks, and kidnapped people before being crushed by the army: some had died fighting, some were executed, others captured and tortured, the rest forced into exile. Alarcón, who had begun his adult life assembling homemade bombs and forcing locks, still had a framed poster from the 1970s, now yellowed with age, showing him with three of his tupamaro comrades and offering a reward from the military for their capture. The pallid boy in the photo, with his long, shaggy hair, his beard, and his astonished expression, was very different from the man Ryan knew, a short, wiry gray-haired man, all bones and sinew, intelligent and imperturbable, with the manual dexterity of an illusionist.

These days Alarcón was professor of artificial intelligence at Stanford University and competed as a triathlete with Ryan, who was twenty years his junior. Aside from their shared passion for technology and sport, both were men of few words, which was why they got along so well. They both lived frugal lives and were bachelors; if anyone asked, they’d claim they’d seen too much of life to believe in schmaltzy love stories or to be tied down to one woman when there were so many willing beauties in the world, but deep down they suspected that they had ended up alone out of sheer bad luck. According to Indiana Jackson, growing old alone meant dying of heartache, and though they would never have admitted it, secretly they agreed.

Within minutes Pedro Alarcón had picked the lock on the main door and managed to disable the alarm, and both men stepped into the house. Ryan used his cell phone as a flashlight, keeping a tight grip on Attila, who was ready to do battle—straining at the leash, panting, teeth bared, a low growl coming from deep in his throat.

In a sudden flash, as had so often happened at the most inopportune moments, Ryan found himself back in Afghanistan. Part of his brain could process what was happening: post-traumatic stress disorder, the symptoms of which were flashbacks, night terrors, depression, and fits of crying or rage. Ryan had struggled to overcome the temptation to commit suicide, recovered from the addictions to alcohol and drugs that a few years earlier had all but killed him, but he knew they could come back at any time. He could never let his guard down; these symptoms were his enemy now.

He could hear his father’s voice: no man fit to wear the uniform would bitch about having carried out orders or blame the navy for his nightmares, war is for the brave and the strong, if you’re scared of blood, get a different job. Another part of his brain reeled off the statistics he knew by heart: 2.3 million American combatants in Iraq and Afghanistan over the past decade, 6,179 dead, 47,000 wounded, most with devastating injuries, 210,000 war vets being treated for the same syndrome he suffered from, to say nothing of the epidemic that had devastated the armed forces: an estimated 700,000 soldiers suffering psychological problems or with brain damage.

And still there was a small, dark corner of Ryan’s mind—a part he could not control—that was trapped in the past, in that night in Afghanistan.

A group of Navy SEALs advances through the desert terrain, heading for a village in the foothills of the mountains. Their orders are to conduct a house-to-house search, dismantle the terrorist cell apparently operating in the region, and bring prisoners back for interrogation. Their ultimate objective is the elusive phantom of Osama bin Laden himself. It is a nocturnal mission, aiming to surprise the enemy and minimize collateral damage: at night there will be no women in the market, no children playing in the dust. This is a secret mission requiring speed and discretion, a specialty of SEAL Team Six, trained to operate in desert heat, in arctic cold, to deal with underwater currents, soaring peaks, the pestilential miasma of the jungle. The night is cloudless, moonlit; Ryan can make out the village silhouetted in the distance and, as they move closer, a dozen or so mud huts, a well, and some livestock pens. The bleating of a goat breaks the spectral silence of the night, making him start. He feels a tingling in his hands, in the back of his neck; he feels adrenaline course through his veins, his every muscle tense; he can sense the men advancing through the shadows with him, who are a part of him: sixteen brothers but a single beating heart. This was what the instructor had hammered home during BUD/S training, the infamous Hell Week during which they were pushed beyond the limits of human endurance, an ordeal that only 15 percent of men come through; they are the invincibles.

“Hey, Ryan, what’s up, buddy?”

The voice came from far away, and had called his name twice before he managed to come back from the remote village in Afghanistan to the deserted mansion in Tiburon, California. Pedro Alarcón was shaking his shoulder. Ryan snapped out of his trance and sucked in a lungful of air, trying to dispel the memories and focus on the present. He heard Pedro calling to Amanda a couple of times, careful to keep his voice low so as not to scare her, and then he realized he had let Attila off the leash. He searched for him in the beam from his cell phone and saw the dog dashing around, nose pressed to the floor, bewildered by the combination of smells. Attila was trained to sniff out explosives or bodies, whether alive or dead. With two taps on his collar, Ryan let the dog know they were looking for a person. He had no need to use words; he simply picked up the leash, and as soon as he tugged, Attila stopped, attentive, his intelligent eyes questioning. Ryan signaled for him to stay, waiting until the dog was a little calmer. Then they resumed the search, Ryan following a still restive Attila, keeping a tight grip on the leash, through the kitchen, the laundry room, and finally the living room, while Alarcón kept watch at the front door. Attila quickly led him to the packing crates, snuffling between the planks, teeth bared.

Shining his flashlight between the crates at which Attila was pawing, Ryan saw a huddled figure and was immediately plunged into the past again. For a moment he could see two trembling children huddled in a trench—a girl of four or five with a scarf tied around her head, her huge green eyes wide with terror as she clutched a baby. Attila growled and tugged at the leash, jolting Ryan back to the reality, to this moment, this place.

Exhausted from crying, Amanda had fallen asleep inside the packing crate, curled up like a cat in an attempt to keep warm. Attila immediately recognized the familiar scent of the girl and sat back on his hindquarters, waiting for instructions while Ryan woke Amanda. Awkwardly she straightened her cramped body, blinded by the light shining into her eyes, not knowing where she was. It took a few seconds for her to remember what had happened. “It’s me, Ryan,” he whispered, helping her out of the crate. “Everything’s fine.” When she recognized him, she threw her arms around his neck and buried her face in his broad chest while he stroked her back reassuringly, murmuring words of affection that he had never said to anyone, his heart aching as though it were not this spoiled little girl wetting his shirt with her tears but the other girl, the girl with green eyes and her little brother, the children he should have rescued from the dugout, carefully shielding them with his arms so that they would not see what had happened. He wrapped Amanda up in his leather jacket and held her up as they cut through the garden, collecting the backpack she had left under one of the bushes, and headed back to his truck, where they waited for Pedro Alarcón to lock up the house.

Amanda was choked with tears, and with a cold that had been brewing for some days before viciously flaring up that night. Ryan and Alarcón thought she was in no fit state to go back to school, but when she insisted, they stopped by a drugstore, where they bought a cold remedy and rubbing alcohol to remove the fluorescent paint from her arms. They stopped for breakfast at the only café they could find open—linoleum floor, plastic chairs and tables. The room was warm, and the air was filled with the delicious smell of fried bacon. The only other customers were four men wearing overalls and hard hats. A girl with hair gelled into porcupine spikes, blue nail polish, and a sleepy expression took their order, looking as though this was the end of an all-night shift.

While they waited for their food, Amanda made her saviors promise they would not say a word to anyone about what had happened. She, master of Ripper, expert in defeating evildoers and plotting dangerous adventures, had spent the night in a packing crate, a mass of snot and tears. With a couple of aspirin, a cup of hot chocolate, and a stack of pancakes and syrup in front of her, the escapade she recounted to them sounded pathetic, but Ryan and Alarcón did not make fun or scold her. The former methodically tucked into his eggs and sausage, while the latter buried his nose in a cup of coffee—a poor substitute for maté—to hide his smile.

“Where are you from?” Amanda asked Alarcón.

“From here.”

“You sound foreign.”

“He’s from Uruguay,” Ryan interrupted.

“A tiny little country in South America,” Alarcón explained.

“This semester I have to do a project on a country for my social justice class. Do you mind if I use yours?”

“I’d be honored, but you’d be better off picking somewhere in Africa or Asia—nothing ever happens in Uruguay.”

“That’s why I want to use it—it’ll be easy. For part of the presentation, I have to interview someone from the country I’ve chosen, probably on video. Would that be okay?”

They swapped phone numbers and e-mail addresses and agreed to meet up in late February or early March to film the interview. At seven thirty that miserable morning, the two men dropped the girl off in front of the gates of her school. She said good-bye, shyly kissing each of them on the cheek, hiked her backpack onto her shoulder, and walked away, head down, dragging her feet.