Полная версия

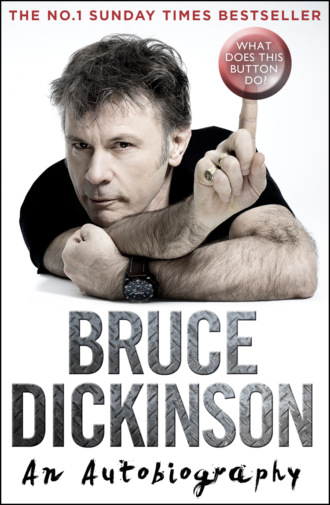

What Does This Button Do?: The No.1 Sunday Times Bestselling Autobiography

‘Fuck off, you twat,’ was the robust response.

At home in Sheffield I was enrolled in the Christian Union, where I wore a little badge and was encouraged to read The Screwtape Letters and lots of other rather less inventive tracts, some of which covered subjects like masturbation and marriage. Confused, I thought, Did they go hand in hand?

My parents were a bit bemused, having seldom been near a church since I half-swallowed one when I was nine months old. However, they tolerated it on the basis that it seemed harmless enough and gave me something to do on Sunday mornings.

Not too long after this, hormones kicked in, and I began to look at girls in a rather different light. I no longer wanted only to convert them; there was something more that you could diddle about with. I just couldn’t put my finger on it.

My school friend Tim was discussing the subject of exactly where to put fingers. Incredibly, it was the only time anybody had spoken about sex thus far, other than being told it was, by and large, sinful, except for making babies. Further in-depth enquiries about what this fairly sexually advanced chap got up to revealed that he did something on his own time involving a sock and his pyjamas.

‘Then what happens?’ I asked, trying to picture the scene.

So he told me.

‘Really?’ This was all news to me. Well, God hates a coward, as the expression goes, and my monastic existence turned into an onanistic one. As for Sunday school, given a choice between wanking yourself silly and Christian Union, there was a clear winner. It was masturbation and libraries that saved my soul from the narrow-minded proselytising and a stifling, evangelical straitjacket, and thank God for that.

But I never got around to telling you the good bit about God and his mysterious ways.

The official custodian of our spiritual health at Birkdale was the Reverend B.S. Sharp, at the time the vicar of Gleadless at the splendidly dark Victorian Millstone Grit church. Unlike the part-time evangelical types, ‘Batty’, as his nickname suggested, was more than a little eccentric, and he was stone deaf. As reverends go, he was regarded as being harmless.

Batty would conduct hymn practice, and the entire school would traipse into his church and commence singing while he walked up and down the aisle waving his arms about, seemingly oblivious to the out-of-time, out-of-tune and smirking schoolboys (no girls, of course). As he passed me – I was standing at the end of a pew – singing, or rather mumbling, he paused; he cocked his head, rather like a parrot, and peered round at me. I suspect he was positioning his good ear.

‘Sing up, lad,’ he said.

So I sang a bit louder. He brought his entire face close to my mouth. I realised he was missing a lot of teeth and I tried hard not to laugh.

‘Sing up, lad.’

Well, I like a challenge, so I yelled at the top of my lungs, and once I started I didn’t stop. The embarrassment left me and I carried on to the end of whatever verse it was in whatever hymn. I confess that it felt wonderful – not that I would admit it at the time.

He stood up and waved his arms about a bit more, then leaned back over to me.

‘You have a very fine voice, boy,’ he said. And then he strode off down the aisle and I never saw him again.

Like I say, nothing in childhood is ever wasted, and if there is a God, he or she is full of mischief.

Sadly, the choirmaster at Oundle didn’t share Batty’s enthusiasm for my dulcet tones. It became clear that singing, as in singing in church, was very undesirable, although to describe the school chapel as a church would be to do it an injustice.

Oundle’s chapel had pretensions of being a cathedral at the very least. It had a choir and the usual, and possibly verifiable, rumours about choirboys and choirmasters. The school choir dressed in frocks and had their free time spirited away from them in fruitless praising of the ineffable one until their voices broke.

There was a singing test, which was compulsory. I was very proud to say that I failed in spectacular fashion. Every note that was white on a keyboard was black when I returned the favour. I was given a chit – a piece of paper – to deliver to my housemaster. On it was written: ‘Dickinson – Sidney House, NON-SINGER’.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.