Полная версия

Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer

After Mrs Adam Girvan met Lieutenant Ronald Mellor, they fell in love. Ron, who by the end of the war had been promoted to Major, was great company, very funny, sensitive, intelligent and articulate; his Indian upbringing and racial mix made him seem unusual to the woman with a pure Highlands bloodline; and when she was with him her natural beauty was only emphasized by the glow of love that surrounded her like a halo. ‘Ron was very exotic, and I can see why Anna was captivated,’ thought Rona, Alasdair Gillies’s twin sister. Anna’s heart was touched by the subtly lingering sense of sadness that Ron had carried with him ever since the death of his difficult mother; some felt that the fact that he couldn’t even remember his father accounted for his faintly other-worldly air of permanent bewilderment.

They decided to make their lives together. But there was a problem: Anna was still married. Divorce in those days was very rare, and not in the vocabulary of the Bonar Bridge Mackenzies. All the same, Anna communicated her intentions to Adam Girvan. When she returned to the United Kingdom at the end of the war, they divorced: Anna discovered that as soon as Adam had learned of her relationship with Ron Mellor, he had cleaned out their joint bank account.

‘I remember my father wasn’t very chuffed about the divorce,’ said her sister Jessie. ‘But Mum didn’t say much.’ But would you have expected her to? As Jessie pointed out, ‘You didn’t even talk about pregnancy. Granny was very, very strict.’ Anna went up to Bonar Bridge and made peace with her parents. In that Highland way of keeping intimate matters close to your chest, the divorce was kept secret from everyone, including her children. ‘My mum told me Anna had been married before, but she never told my dad,’ Rona described a typical piece of Mackenzie behaviour. ‘I wasn’t surprised about it – things happen,’ said Uncle John, customarily phlegmatic. Joe didn’t learn about it until he was in the Clash. ‘I’ve just found out that my mum was married before,’ he said, tickled. ‘She seems to have been a bit of a goer.’

Ron Mellor made his way to London, and took a job in the Foreign Office as a Clerical Officer; considered highly prestigious, the FO only admitted candidates considered high fliers; they were subjected to a supposedly rigorous security check. Soon Ron and Anna were married: in a picture of Ron and Anna on their wedding day on 22 October 1949, her new husband’s caddish Clark Gablethin moustache and double-breasted suit give him the appearance of an archetypal Terry Thomas marriage-wrecker – which, in a way, he was. The newlyweds moved into a top-floor flat, up four flights of stairs, at 22 Sussex Gardens in the seedy area of Paddington. They lived there for two years. Meanwhile, Anna took a post as sister at one of the largest hospitals in London, St George’s by Hyde Park Corner.

Ron travelled to the Foreign Office in Whitehall every day, studying the intricacies of sending and decoding messages which would earn him the job of cypher-clerk, a role whose top-secret nature was only emphasized by the growing Cold War. In the manner of those employed in such positions, he laid down a smokescreen by describing himself to his relatives as ‘third secretary to the third under-secretary’. (Years later, at the beginning of the 1970s, after the Mellor family was once again settled in Britain, Alasdair Gillies remembered his uncle Ron telling him of a visit that Prime Minister Edward Heath made to meet Marshal Tito in the Iron Curtain state of Yugoslavia. ‘Ron was roused out of bed to go with him to send coded messages back to London from the embassy.’)

David Nicholas Mellor was born on 17 March 1951, in Nairobi in Kenya, where Ron Mellor had been posted after marrying Anna. Soon he was given a further overseas posting, to Ankara in Turkey. For unclear reasons, the Mellor family had been in Germany immediately prior to this move to Ankara. Booked on the Orient Express from Paris to Istanbul, they travelled from Germany to the French capital by road. Running late, Ron telephoned ahead: employing diplomatic protocol, he managed to delay the departure of this prestigious train, and Anna told her younger son about running down the platform under the eyes of the waiting passengers.

In Ankara on 21 August 1952 Anna Mellor gave birth to her second son, John Graham Mellor. Brought up with Turkish help around the family home, he learnt a pidgin form of the language. His earliest memory, as he told me, was of the moment his brother leant into his pram, giving him a digestive biscuit.

Ron Mellor’s skills at coding and decoding messages did not go unappreciated by the powers that be. He was transferred to the British embassy in Cairo in Egypt, which was paying close attention to the zealous proclamations of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian leader, soon to bring about the Suez Crisis with his nationalizing of the vital canal. In this John Le Carré world the Mellor family moved into a house vacated by a certain Donald Maclean and his wife Melinda – Anna complained about Melinda’s terrible taste in curtains and had them replaced. Ron Mellor would regularly have lunch, which invariably consisted of little more than a bottle of vodka, with a close friend of Maclean’s called Kim Philby. These two men, along with Guy Burgess, would defect to the Soviet Union; this trio of intellectuals had been working for Moscow. Interestingly, as the years progressed, Ron Mellor revealed himself more and more to be almost Marxist in political philosophy, an undisguised leaning that might seem surprising for someone working at such a level.

The social whirl of diplomatic functions meant, as it did for many of the embassy staff, that alcohol became a staple part of Ron and Anna Mellor’s diet. Ron was always partial to a gin and tonic, and was fastidious that it was served with a slice of lemon. Anna had a wardrobe of cocktail dresses, and forced herself to learn bridge, which she secretly detested. ‘But that was what you had to do as an embassy wife,’ pointed out Maeri, another of Joe’s Mackenzie cousins. Anna would laugh scathingly to her sisters about a publication called Diplomatic Wives, the in-house magazine of embassy spouses. ‘Anna wouldn’t complain. She wasn’t the complaining type. But I don’t think she liked Cairo,’ said her sister Jessie. As they grew older her two sons David and John learnt to serve drinks and cutely play the parts of junior waiters. A story that attained the status of legend within the Mackenzie family told of how when the boys were taken by Anna Mellor to get a haircut in Cairo, Johnny wriggled so much that the Arab barber became so angry and upset that he stuck his head under a tap to cool down.

In 1956, two months before the invasion of Suez by British and French troops, Ron Mellor was transferred again, to Mexico City. Of all Ron’s overseas postings this was where Anna was happiest; in a photograph of her with her two sons in Mexico City she wears curved Sophia Loren-like sunglasses that emphasize her film-star beauty: she looks impossibly glamorous, rather like the sort of girls you would find backstage at a Clash gig. As though to underline his wife’s sophistication, Ron bought a boat-sized 1948 Cadillac in which to transport his family.

Not long after they had arrived in Mexico City, the area was struck by a devastating series of earthquake tremors. One night while they were having dinner the lights started swinging back and forth; Ron and Anna ran out of the house carrying David and John and sat in the middle of the lawn away from any swaying structures. At first they didn’t notice John when he slipped away. ‘I remember the ’56 earthquake vividly,’ he told me, ‘running to hide behind a brick wall, which was the worst thing to do.’ When the earthquake tremors seemed to have calmed, Anna attempted to bring some calm and normality back into the boys’ lives by bathing them together. Suddenly the water started to slop from side to side as the tremors returned. That night Ron and Anna moved the boys’ beds into their room, so they could all die together.

It was in Mexico City, however, that Ron Mellor developed an ulcer; and he was troubled by the altitude. In 1957 the Mellor family were shipped back to London, and Ron may have had an operation.

5

BE TRUE TO YOUR SCHOOL (LIKE YOU WOULD TO YOUR GIRL)

1957–1964

Before 1957 was over, the Mellor family again was on the move overseas: Ron was posted to work with the British embassy in Bonn, the then capital of West Germany. ‘I was eight when I came back to England, after Germany,’ Joe Strummer told me, forty years later. ‘Germany was frightening, man: it was only ten years after the war, and what do you think the young kids were doing? They were still fighting the Germans, obviously. We lived in Bonn on a housing estate filled with foreign legation families. The German youth knew there was a bunch of foreigners there, and it was kind of terrifying. We’d been told by the other kids that if Germans saw us they would beat us up. So be on your toes. And we were dead young.’

Aware of the need for some kind of stability in the lives of his family members, Ron Mellor decided that he must establish a permanent home in England, his adopted country; his sons lost a new circle of friends with every overseas move. One consequence of this seemed to be Johnny’s almost acute sense of self-reliance and self-awareness. But for David, Ron and Anna’s eldest son, the constant break-up of friendships, accompanied by that nagging wonder of whether everyone would always disappear from his life with such sudden ease, seemed to be having a negative effect: increasingly quiet, he often seemed lost in thought. This struck a nerve with Ron: his memories of his own traumatic childhood would rise when confronted by the hushed sense of ‘otherness’ that floated about David. In turn it was hard for sensitive David to be unaffected by the way this unhappy childhood was so deeply etched in his father’s being; it was as though they were cross-infecting each other with indeterminate but undeniable suffering. Yet David showed no evidence of Ron Mellor’s tendency towards volatile mood swings. ‘Ron loved being able to just reminisce,’ said Gerry King, Joe’s paternal cousin, remembering her visits to the Mellors. ‘But he would go into moroseness. I felt it once or twice – some pity. I think he’d had such a sad life, really.’

Ron Mellor’s plan to buy a house in London hit a problem: he had no savings, so where could he raise the money for a deposit on a property? There was a potential solution. In India he had always been the favourite of his half-aunt Mary, who had married a rich Pakistani man by the name of Shujath Rizvi, and had no children of her own. (The somewhat formidable Mary Rizvi lived in a state of pasha-like splendour, with one room in her palatial home reserved simply for her Pekinese dogs.) Ron mustered up his courage and wrote a letter to his half-aunt: could he borrow £600 for the deposit on a house? Aunt Mary immediately gave him the money. Back in London in 1959 for what he knew would be a three-year stint in Whitehall, Ron Mellor made a down-payment on a three-bedroomed single-storey house just outside Croydon in the south-east of London. The property, at 15 Court Farm Road in Upper Warlingham in Surrey, was being sold for £3,500, cheap even by property prices of the day, a reflection of its dolls-house size. A cul-de-sac, Court Farm Road wound round the side of a steep hill that formed one side of a valley that sloped down to the main Godstone Road. Located on a corner of Court Farm Road, No.15 was the last of four identical bungalows, built in the 1930s and – partially due to their hillside perch – having something of the appearance of Swiss mountain chalets, a look that distinguished them all the more from the larger detached and semi-detached houses that made up the rest of the street.

When the Mellor family moved into the bungalow, David and Johnny were sent to the local state primary school in nearby Whyteleafe. Joe Strummer would later seem to dismiss the home bought by his father as ‘a bungalow in south Croydon’. But this is exactly what it was; for once he was not disguising his past. Presumably dictated to by the maxim that location is everything, Ron Mellor had bought what was essentially a miniature version of the adjacent properties in the neighbourhood. In fact, it was typical of English houses built in the 1930s, and – as did much of Britain at the beginning of the 1960s – it still had much flavour from that decade. Through the black-and-white front door was a hallway-like corridor: to the left was Ron and Anna’s bedroom. Opposite, on the right-hand side, was a small kitchen whose window faced the road; further along on the left was David’s bedroom and the bathroom; and on the right was the sitting room and Johnny’s small bedroom. ‘They never spent a lot of time worrying about pretty carpets or furniture. It was just kind of bricks and mortar and that’s where they were,’ said a visitor. On display at 15 Court Farm Road were exotic artefacts gathered at Ron’s various international ports of call: bongo drums, a wooden framed camel’s saddle, pouffes made of Persian leather. Although a television did not appear at first, there was a large radiogram of the type later featured on the sleeve of the ‘London Calling’ single. ‘My parents weren’t musical at all,’ Joe later told Mal Peachy. ‘They had sort of Can-Can records, from the Folies Bergère, and that was about it. Maybe a few show tunes like “Oklahoma”, that sort of thing. I remember hearing Children’s Favourites [a request show broadcast at nine o’clock every Saturday morning] on the BBC, things like “Sixteen Tons” by Tennessee Ernie Ford.’

Visitors would sometimes feel the house seemed run down – the diplomat and his wife, after all, had been used to servants and had lost the habit of home maintenance. Some improvements were made. French windows were installed, letting in far more light and a view of the disproportionately large garden and lovely apple orchard. The patio that separated the living-room and garden was extended. But little else was done to the home that would serve the Mellors for over two decades. Although slightly shabby, 15 Court Farm Road was an extremely comfortable house. But the sense of alienation in the area was reflected inside it. ‘I think Ron and Anna lived this very weird, isolated life,’ Gerry King remembered of a visit there in the late 1960s. ‘You could imagine them in the times of the Raj, as though he had been posted to some obscure place in India, and they are there, sipping their sherry, and going on to whisky. That sort of thing: a feeling of not being real. But there was something very wonderful and lovely about them both. And Uncle Ron also had that gentleness. I felt that he didn’t cope with reality well. But he was a lovely man.’ Yet Ron and Anna’s loneliness was not surprising: like their sons, Ron and Anna had suffered disappearing diplomatic service relationships, and had few friends in London.

Living at 54 Oakley Road, some 500 yards from 15 Court Farm Road, was the Evans family. Richard, the youngest child, was a few months younger than David Mellor and a year older than Johnny Mellor. Soon after the Mellor family had moved into their new home, the Evans and Mellors met up – he too attended Whyteleafe primary school. ‘It’s just a village primary at the bottom of the hill. That’s where I went. That must’ve been where we met.’ The two families became close; Richard quickly came to regard David Mellor as his best friend. ‘It was Johnny-and-David, a kind of Scottish thing. “Johnny” – that’s what his mother always called him. David is nine, I’m nine. He’s very quiet, very withdrawn, but there’s something very comfortable about being with him. And I would literally sit there with him not saying anything for half an hour and it was OK, you didn’t have to. He was my mate, my best mate. But all three of us played together.’

Hardly a day would go by when Richard Evans was not over at the Mellor house: ‘My recollection of it was that I was always there and it was always a very warm house. They never locked it up. The door was always open. My parents were really security conscious: our house had been burgled. But Anna was not, the house was always open, they never locked the door. Yet they never got turned over. Maybe it was just the atmosphere of the place. But it was always an open house.’

Anna’s engaging and welcoming personality meant that Richard very quickly grew close to her (‘hugely’), and she took on the role of a surrogate aunt. ‘I was closer to her than I was to my own mother, emotionally. It was Anna I spoke to about my issues, my successes and failures. No disrespect to my mum, who was hugely strong in other ways, but it was Anna who was the emotional pillow or rock or whatever. She was tiny, not more than about five feet one, but one of those people who is physically diminutive but whose heart is huge. She was very quiet, and whenever you went there there was always a cup of tea or sandwiches. She’d be fussing around, making you feel comfortable, and would have just made a cake or whatever. She was constantly caring for you. I’m absolutely sure – and it was one of the great joys of Joe – that he had his mother’s huge generosity.’

As he grew into his late teenage years, Johnny Mellor and his father were in increasing conflict, as they played out a classic scenario of a son wanting to escape from his father to find his own course in life. To Iain Gillies Johnny once glumly described Ron Mellor as being like ‘an old bear in a bad mood’. Richard Evans agreed: ‘Like a bear. Sometimes quite angry. You walked around him and weren’t quite sure how it was going to be. If he was purring, it was OK, you could have a really good time with him. But if he was growling you just got the hell out of there. I think Joe and David were wary of him too. There was a weird juxtaposition between the soft, downy-faced mother, with really soft skin, and the dad. I think that’s how they got along.’

As Johnny Mellor grew into Joe Strummer, he displayed considerable behavioural similarities to his father, rendering the earlier conflict between them even more archetypal. ‘Joe and I had this big gap from around the time of the Clash until the last three years of his life, one of about twenty years,’ said Richard. ‘The first thing I noticed when I saw Joe as a grown man was, “Fuck, he’s got his dad’s eyes.” His dad’s eyes were always quite wild and quite irritated-looking, quite red, as though he needed to have an eye-bath. The eyelids were almost separated from the eyeball. Joe’s were the same. It was bizarre, because I looked at Joe as a 47-year-old man, and I went straight back to his dad. His dad was wild-eyed and erratic.

‘Joe’s dad was very critical. God knows why he was in the diplomatic corps. [Joe’s ex-partner, Gaby Salter, says that she once heard a story that Ron was being assessed for suitability as a spy but was prevented from doing so because of Anna’s drinking.] He’d rant about inequality. There’s something in there that didn’t add up – as a child I was wary of him. He was a diplomat, but not diplomatic. He was passionate, full of conviction: he was a socialist. That’s Joe’s political aspect – came from his dad. Somehow that doesn’t fit. If you looked at the man, this was not a sharp-suited, smooth-talking diplomat. He was passionate and volatile. He was also exciting – there was an attraction to the man. You can see what that was for Anna: the international lifestyle, but also that the man was mysterious. It could be beautiful or it could be harmful.

‘There was a huge positiveness about Joe, an energy, that everybody liked. I found myself more and more attracted away from David towards Joe, his younger brother. Being a year younger is an issue as a nine-year-old. But I felt drawn towards Joe, as everybody did. He was just a good person, he had a wonderful capacity to just make you feel better about everything. If he had a good idea – “Let’s do this or that” – somehow he turned it into your idea. He’d be the one saying, “Great idea, I wish I’d thought about that.” You’re going, “Did I think of it? Oh, brilliant.” He had that huge ability to make people feel much better about themselves. It was remarkable: at eight years old he had that. It was nothing to do with the Clash: he just had that gift.’

It was a gift, however, that was about to be sorely tested, at the new school that Ron and Anna Mellor had chosen for their two sons, City of London Freemen’s School in Ashtead in Surrey, 20 miles to the south-west of Upper Warlingham.

The school had been founded in 1854 as the City of London Freemen’s Orphan School. In 1926 the Corporation of London moved the school into the country and it reopened in Ashtead Park in Surrey, a gorgeous estate of 57 acres of landscaped grounds, approached by an avenue of lime trees. You might feel that the idea of being sent to a school established to educate parentless children would have struck a sad chord within Johnny Mellor: he spoke later of how he felt abandoned by Ron and Anna when he was sent to CLFS as a boarding pupil, their solution to the dilemma of how the overseas postings were affecting the boys’ education. After the light discipline at Whyteleafe, CLFS would prove traumatic for both the Mellor boys; Johnny Mellor would never sufficiently come to terms with having been sent away to boarding school by his parents for him to forgive them for the wounding created by this apparent desertion in his childhood. So great had been that hurt that, according to Gaby Salter, Joe’s long-term partner for fifteen years, he was still berating his mother over being sent to CLFS as she lay dying in a cancer hospice twenty-five years later. Part of him felt that his entire life would have been different if he had not been sent there – though that experience was a formative one for the person he was eventually to become.

But naturally Johnny was not showing any indication of such emotion on his first visit to the school. ‘Loudmouth!’ was Paul Buck’s very first impression of John Mellor when he saw him at the entrance examination. Of all the fifty or so boys there, aged between eight and ten, the short-trousered John Mellor – one of the youngest and smallest present – seemed the only candidate unbowed by the exam worries: he didn’t seem to be taking it seriously, laughing and making cracks. ‘I just remember him as being a kid who wasn’t bowed by having to take an exam – which can be daunting for a nine-year-old kid.’

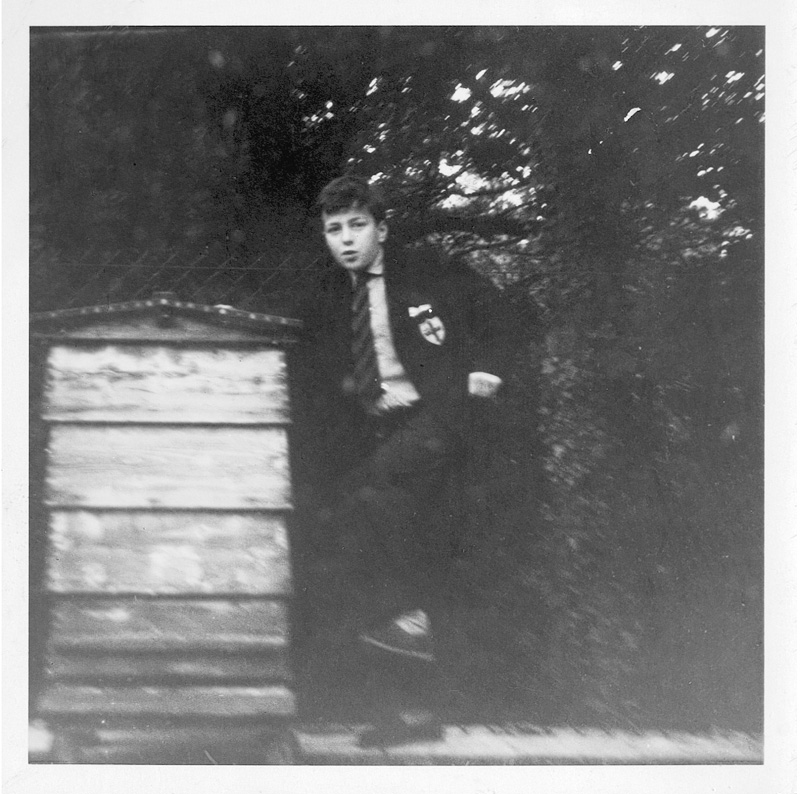

At the beginning of September 1961, dressed in the navy-blue blazers that bore the CLFS coat of arms on the badge pocket, the red-and-blue striped ties of the school neatly knotted at the collars of their white shirts, the regulation blue caps pulled down over their freshly shorn hair, David and Johnny Mellor bade farewell to their parents. Johnny was just nine – because of where his birthday fell he was almost always the youngest in his year – and David ten and a half. Later, in the days of punk, when such a skewed background counted, Joe would claim he had failed the school’s entrance examination and was only accepted because he had a sibling who was already there. This was not true. Because City of London Freemen’s was a public school, however, this led his punk peers to snipe at Joe. Joe never fell back on an easy let-out clause: that his place at the school was a perk of Ron’s job. The Foreign Office paid for David and John Mellor’s school fees, an acknowledgement of the need for some stability in a diplomat’s peripatetic life. (Part of Ron’s employment package was summer-holiday plane tickets to wherever he was stationed; Ron and Anna would add to this themselves with fares paid out for their sons to visit them every Christmas holiday.) There was a number of boys and girls at CLFS whose parents were diplomats or in the military, ten per cent of the school’s 400 pupils. There were many more day-pupils than boarders at CLFS, which added to the boarders’ sense of embattled remoteness; equally unusually for a British boarding school, CLFS was co-educational.

John Mellor in his regulation school uniform. (Pablo Labritain)

Later Joe Strummer recalled his years at CLFS guardedly and defensively, not even mentioning its name until October 1981, when he revealed it in an interview with Paul Rambali in the NME. To Caroline Coon he lied for a Melody Maker article in 1976 that the school had been ‘in Yorkshire’. ‘I went on my ninth birthday’ – in fact it was a couple of weeks after his birthday – ‘into a weird Dickensian Victorian world with sub-corridors under sub-basements, one light bulb every 100 yards, and people coming down ’em beating wooden coat hangers on our heads,’ he told the NME’s Lucy O’Brien in 1986. Paul Buck, who was in the same boarding house as John Mellor, confirmed this. ‘Joe spoke of dark corridors, and basements, and he wasn’t exaggerating. When we started we used to spend most of our time in a dark basement corridor in our boarding house mucking about. There was a recreation room, at the top of the building, very cold and uncomfortable. You didn’t go up there because if the seniors needed to get anybody to do anything they’d go straight there. So we preferred the corridor.’