Полная версия

I'M Only A Child

Wanda Montanelli

I'm Only a Child

I’M ONLYA CHILD

(Stories of abuse and mistreatmentin the denied childhood of child brides)

Wanda Montanelli

Copyright© 2019 Wanda Montanelli

First edition: 7 January 2019, StreetLib Write http://write.streetlib.com

English edition 13 May 2019

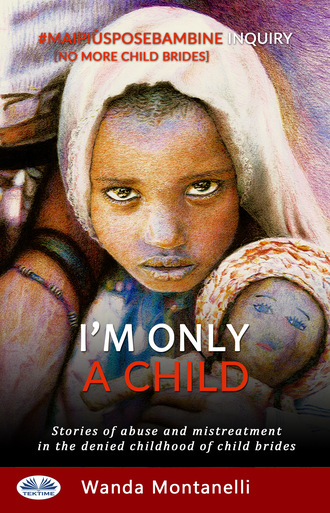

Translator: Linda Thody

The cover picture is from the painting "Bambina Sposa" [Child Bride], created by the artist Michele Zatta in March 2019, to represent the subject of this book.

Published by: Tektime – www.traduzionelibri.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SonoSoltantoUnaBambina/

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, or by any mechanical or electronic means, nor photocopied or recorded, or otherwise disclosed, without the written permission of the publisher.

CHAPTER I

STORIES ABOUT CHILD BRIDES

To all the courageous little girls who startedthe protest against child marriage,and all the others who, although forced to marry,are fighting for a better fate for their own children From dolls to husbandsThese are true storiesThey took place in countries where it is customary to oblige young girls to go from playing with dolls to being controlled by a husband, who is often elderly, a stranger, someone chosen by their familyThe Tortured Child Bride

A Symbol of Human Rights

Sahar Gul’s story is emblematic and a testimony to unacceptable cruelty.

The image of the little girl who her torturers forced into prostitution is a picture of suffering: her swollen eyes, the bruised skin on her face, a burnt ear, her hands – without nails because the vile criminals pulled them off – are covered in dark scabs and wounds.

Everyone who’s seen the photograph of the small victim has felt a surge of revulsion and rebellion. Civil society, the press, social networks, associations, have all made their strong disagreement and condemnation of the child’s persecutor heard.

Sahar Gul refused to be a prostitute and she was massacred

The reason for all this fury was because the little girl refused to be a prostitute. As a little slave, forced into early marriage, she quickly realized there were no limits to the cruelty of her tyrant husband, the soldier Gulam Sakhi. The adult man who, in addition to having violated her innocence, felt he could make money out of her emaciated body, by selling her to his sickening peers.

He claimed powers of life or death over the child and helped by relatives – as cruel and greedy as himself – he made Sahar endure paid sexual encounters, with men of all ages, to make money and profit ruthlessly.

Sahar’s and Gulam’s is one of the many -too many- forced marriages, which when described truthfully, are nothing more than the actions of paedophiles against innocent little girls.

Right from the start, the intentions of the soldier’s entire family unit were to earn money by offering his little wife to sate the appetites of perverts, ignoring the little girl’s protests, her pain, her immense disgust.

An impossible life, then her escape and salvation

What happens in a house where adults hold a minor prisoner? And how does a twelve-year-old girl, caught in the trap, feel?

At first Sahar didn’t realise the irreversibility of her state. They told her that getting married was a duty, a natural event, the only way to exist with dignity, with the man of the house responsible for the entire household. They told her this is what women have to do: get married, obey their husband and have children. They forced her to accept marriage, especially her parents, her mother. How she would have loved to have a sympathetic mother, one she could turn to for help in understanding what was happening to her, how all the other men who claimed her body fitted into the picture: old men, young men, strangers for whom she felt repulsion, who as they got closer to her made her heart seem about to burst from beating so fast, or just stop out of fear.

She hated them. And she hated her husband. She detested all the adults who portrayed marriage as a happy event to her. She found no confirmation of all their promises. She had thought, that although she was being forced to marry, she would find affection, loving gestures, comforting words, nice manners. But there was none of any of this. She was trapped and her husband was a tormentor; neither husband, nor friend, nor relation. A brute. Her mother-in-law and all the rest of the family were even worse than him. And Sahar was only a child.

Sahar didn’t know who to turn to among the people who came and went in her home.

She showed signs of distress when she heard her relatives’ unbelievable words as they insisted – every time a stranger crossed the threshold – in persuading her to whore. She refused, she screamed, she cried; but her husband and in-laws quickly went from words to more forceful methods: they used threats and any other means of coercion to break down the child’s resistance.

It was impossible for Sahar to live with the fear, the sleepless nights, the dread of being insulted and offended every day. The awareness that there would never be either freedom or a future in her life, drove her to react.

One day she ran away and asked the neighbours for help: "They force me to have sex with other men! – she said – If you’re Muslims you have to help me and tell the police what they're doing to me."

The neighbours immediately reported what was happening. The police intervened and summoned Gulam Sakhi who, saying he was sorry, promised to end the torture against Sahar. He asked the little girl to return home.

Unfortunately, the police – after giving Gulam a warning – sent Sahar back home, pretending they believed in the man’s remorse and his words of repentance.

However, when dealing with an ogre, you have to take into account that it is unforgivably foolish to leave a child in his hands. In no story, be it true or a fairy tale, are ogres transformed into lambs by a simple recommendation from the authorities.

After returning home the nightmare just got worse for Sahar

In the little house, a cramped space in the district of Pol-e Khomri in Baghlan province, the worst period began, one of torture for Sahar who, beaten, chained up and left without food, was shut up in a basement. Wounded, insulted, in pain, she was left to the mercy of her relatives – who behaved like true criminals – until, many months later, one of her uncles went to visit her. The man realised that the child’s face was swollen, her whole body covered in bruises, her eyes full of tears. He was astonished. He realised he was faced with inconceivable cruelty.

He immediately decided to report the matter to the police and go public about the disgrace.

He told as many people as possible, as well as the authorities, about the little girl’s scandalous treatment, which was comparable to medieval torture; a violence so brutal as to reduce her to using a wheelchair for a long time when she was no longer able to walk.

The picture of the massacred little girl travelled all around the world. Thanks to the interest of the press, Sahar’s swollen face, her black eyes, her wounded body, her unhappy gaze, were seen all over Afghanistan, and then through websites, blogs, social pages dealing with human rights, the case became an ultra-national disgrace, despite the authorities and the family trying to conceal the sinister and cruel affair.

A committee of inquiry set up by the President

Hamid Karzai, the president of Afghanistan, ordered a committee of inquiry to be set up, following which Sahar’s ineffable husband and criminal relatives were prosecuted by law, with the immediate arrest of her relatives and an arrest warrant issued for Gulam Sakhi who went into hiding. However, the judgment was broadcast on Afghan national television and there were not many places where the man could hide. It was the month of May 2012. In July, Sahar’s mother-in-law, father-in-law and sister-in-law were sentenced to ten years in prison for attempted murder.

But how could someone ever have absolute power over a child-wife?

Sahar's story began in May 2011, when she was only 12 years old, and was sold for five thousand dollars to her torturers, who immediately organised a forced marriage whereby they gained all legal power over the child.

The plan was to exploit her sexually and get paid handsomely by nonchalant paedophiles who, confident of her husband’s consent, were not moved to pity by Sahar’s tears or suffering gaze, and defiled her without any scruples whatsoever.

Sahar Gul’s segregation in the home lasted until the day of her uncle’s intervention, the police’s subsequent action and President Karzai’s decision, following the uproar on the pages of authoritative newspapers around the world.

The Times contributed to the dissemination very effectively in its Afghan publications, with articles entitled "Let’s break the deathly silence on the status of women".

Newspapers, magazines, blogs, intensified the public debate until the parliamentary institutions approved a law making “domestic violence” a crime.

So there began in the country an acknowledgement and a process of civilisation of a part of society that still considers powers of life or death over wives to be legitimate, even if they are only little girls. But this is only an encouraging start because the outcome of the story leaves a bitter taste in the mouth.

Ten year prison sentences for the torturers which they don’t serve

Although the case created an outcry in international public opinion, after Sahar’s three torturers were sentenced to ten years in prison, the Court – during a further hearing in a half-empty courtroom – ordered the release of the three people responsible, in the absence of counterparties and the ministerial authorities.

The Court of Appeals subsequently condemned the torturers to five years, with the possibility for the victim to claim damages.

During the trial, Sahar took refuge with the Women for Afghan Women Association, the organisation which takes care of abused Afghan women, offering them legal protection and hospitality in specifically organised shelters.

On International Women's Day in 2012, an Internet café for women was opened in the Afghan capital, Kabul, in the name of Sahar Gul.

What with the acknowledgements of civil society and the feeling of having done the right thing Sahar realised there was a ray of light for her, even if unfortunately her disappointments were not over. She alternated between moments of hope and others of disappointment. She knew that unfortunately the process in the courts was not complete; she would gladly have done without further ordeals, interrogations, confrontations with those who had wronged her. She suffered in seeing her relatives again, and each time hoped it would be for last time. One day her bitterness was rekindled because a further ruling ordered the release of her torturers.

Sahar nevertheless decided to look to the future. With the help of new friends and the assistance -including psychological- of the association, the girl tried to leave the pain she will never forget behind her. She began to study, learning the first rudiments of education, starting from scratch. In fact, she was illiterate at the time of her marriage.

Now she wants to give a positive direction to her life. She dreams of engaging in politics to put actions and laws in place that prevent other women suffering as she suffered. She wants to give back the good and the help received. Instead she intends to forget the wickedness so that it’s no longer part of her reality and her thoughts.

Maha, from dolls to a husband

“My father made me get married because he had heard about a rape and he was afraid it might happen to my sister and me as well. I didn’t have a choice.”

This is what Maha says, a thirteen-year-old who got pregnant at a very young age. Her husband, Abdullah, is ten years older than her. Both are Syrian refugees fleeing the war, who found refuge in Jordan. Abdullah, young Maha’s husband, also tries to explain the reasons for child marriages: "If we were still in Syria – he says – we wouldn’t have got married, she’s too young. But there were often rape attacks in the camp where we live and her father was afraid it might also happen to Maha".

In these places, every day you try and find protection from the bombs, and it’s difficult to do so and survive, but no more difficult than trying to defend yourself from poverty and fear of violence.

These are the main reasons why a high number of parents force their daughters into child marriages.

In a quarter of the marriages registered in Jordan amongst the Syrian refugee population the bride is under eighteen, reports Save the Children that has collected data and testimonies by the baby brides in its dossier “Too young to marry”.

Child marriages were always fairly widespread in Syria before the war, when approximately 13% of brides were little more than children.

Then when war broke out the phenomenon increased exponentially. Nowadays in Jordan approximately 25% of Syrian brides are younger than 18, and in about half the cases the girls are forced to marry men at least ten years older than them.

The phenomenon is on the increase if you consider that in 2011 the marriages involving a baby-bride were 12% of all marriages. That number increased to 25% in 2013, and this tendency – that includes a quarter of the female population – has remained the same over the following years.

Maha and Abdullah, spouses against their will

“My future has been stolen from me – says Maha with a hint of sadness in her eyes – and my life is lost. This is not what I dreamt of for myself. I didn’t want to shut out every possibility of looking towards the future with the hope of being happy”.1

What does happiness mean for Maha, if not being able to study, become emancipated and achieve financial independence?

Like her many girls, due to forced and child marriage, have to leave school, and stop dreaming of living in a better society, in a place where women’s rights, and the rights of people in general, are respected.

In the Zaatari refugee camp, in the semi-desert area of the largest camp that exists in the north of Jordan, 80 thousand refugees live in precarious conditions. Some live by the day hoping for government aid to survive and some, to give meaning and organisation to their lives, launch business ventures, small shops offering poor things or small craft enterprises.

In one of the thousands of tents in the camp we find Nadia, another child bride just 15 years old who, like Maha and many others, is aware she does not have a future:

"Ever since I was a child – says the girl – I dreamt of studying nutrition at university. I dreamt of a house and I planned to get married only after completing my education. Instead, my future has been stolen from me and my life is lost. Everything has been destroyed".2

It’s not always possible to come to the rescue of these young girls who would be so interested in growing, developing themselves and planning their own lives.

For some years now there have been numerous organisations that have implemented programmes to help children in war zones, or otherwise support young people living in rural areas where it is difficult to survive: Amnesty International, Unicef, Save the Children, Amref.

In 2011 the Elders – an international organisation of pacifists and human rights defenders – launched a global partnership against child marriages called Girls Not Brides, which currently includes more than a thousand associations that work for the common goal of abolishing child marriage by the year 2030.

This project is highly involving for anyone who feels committed to fighting for the rights of the weakest. The group I belong to has joined Girls Not Brides and is strongly motivated. So, the monitoring centre for the safeguarding of equal opportunities (Onerpo) chaired by Aura Nobolo, is among the organisations fighting for this principle of civilisation.

Working in partnership through social networks, we disseminate the group’s aims and initiatives on the Facebook page "No more child brides" (#maipiùsposebambine).

Based on the network shares we immediately realised that there is considerable sensitivity on the part of men and women who, like us, hope for decisive action at all levels, both national and international, so the common project to abolish child marriage in every country in the world is fully achieved.

Child marriages in Mexico. The story of Itzel married at 14 years old

Itzel met Jesùs when they were children. She liked him and fell in love with him at 14, when he was a handsome boy of seventeen, as happens to lots of girls, all over the world. But this was Mexico and adolescents often get married at a very early age. According to United Nations information 6.8 million Mexican citizens are married before age 18.

Itzel married Jesús, convinced by her family that this was the best thing to do for the good of them all. But the girl didn’t know her choice would affect her for the rest of her life.

She left school and stayed at home to do the housework and look after the animals.

Her life was spent in loneliness, in a small house, with a little bit of countryside around it.

The days were monotonous and tiring, lived with little enthusiasm and no smiles; lots of duties, very few rights. But nobody could take away her right to dream: to imagine her life could be different, to remember how carefree she was before, when she could go out, go and see her friends, joke with them, go for walks, go to school.

Itzel remembered that at one time she had wanted to be more informed and educated, learn a profession and have a job; but now she was just a goat keeper.

As she ate her frugal meal alone, Itzel was sad and would have liked to tell all young girls: “Think very carefully before you get married. Above all, remember to study. I regret not having continued my education now and I wonder if life will ever give me another chance. I would so like to go back school".3

Not really fully understanding the problem of child marriage, Itzel experienced it first-hand and realised she had precluded any possibility of personal growth for herself. She therefore decided to follow the advice of a former classmate and turned to an association to obtain logistical support to get out of that situation. She was welcomed and helped so she was able to attend some training courses, regain her self-esteem and start to think of a better future.

The Girls Not Brides organisation, which is present in Mexico as everywhere else in the world, is very effective at supporting these lost girls who don’t know who to turn to. Often in the villages, acquaintances and family members tend to convince the girls that theirs is an unavoidable fate, while in actual fact they are only adolescents or very young girls with their whole life ahead of them.

Without help they certainly couldn’t do anything but submit to the wishes of their relatives, and this is why the associations’ work is increasing significantly. The measures to assist these girls begin with a preventive action, aimed at preventing them from being forced to leave school to get married. This action is aimed at families, with meetings in the villages, where all the dangers that arise from child marriage are explained and described. Through documentaries, examples and direct testimonials the parents are made to understand that pregnancies at a very young age entail many dangers. The risks that girls face when they give birth to a child before age 18 are explained to them, ranging from spontaneous abortion, infant mortality, to serious health consequences during and after pregnancy.

The commitment of the activists of the humanitarian associations is constant, and is targeted at very poor families who live in rural areas of Mexico such as Chiapas, Guerrero and Veracruz, where without support they would have absolutely no chance to improve their condition and understand that 40% of the population married at an early age represents a human problem that weighs on the entire social economy.

Nujood, the courage to divorce at 10 years old

“I want a divorce.” This was the unpredictable declaration of a little girl who stood before the judge and expressed her intention to free herself from the noose of her marriage.

Nujood Ali, born in a small village in Yemen in 1998, is co-author of a book about her story translated into 17 languages, and is the youngest divorcee in the world.

Because of the family’s poverty – when the girl was only nine years old – her father accepted a marriage proposal of a thirty-year-old. So Nujood Ali was forced to leave school to be a wife. She left her family and went to live with her groom.

She cleaned the house, spending her days between daily sexual violence alternated with beatings, which her husband didn’t spare her even in the presence of his own mother, who, not only did not defend her, but supported the man’s right to do what he wanted to the little girl’s detriment.

Nujood Ali was only ten years old and only recently married when she decided she had had enough. She wanted to escape the harassment of a husband in his thirties who had taken away the disenchantment of being a child and made her fall into a kind of hell.

It was a woman in her family who helped her, giving her precious advice. Dowla, her father ‘s second wife, who told her to run away and go in search of a law court.

So she ran away. Having reached a court she asked a magistrate to help her. A complaint was lodged and in the meantime Nujood Ali was housed in the home of another magistrate who then asked an association that fights child marriage to intervene.

The centre’s activists, supported by a lawyer, started legal proceedings that would be an example to many other girls in the same conditions.

Nujood Ali went against her own family, who made her marry to obtain a modest dowry from her betrothed, and at the same time get rid of a mouth to feed at home.

The lawyer Chadha Nasser, who defended Nujood Ali free of charge, accused her husband of having broken the law by raping the little girl, and her father of having lied about his daughter’s age.

During the debate Nujood Ali refused the judge’s proposal to return to her husband after an interval of five years. She couldn’t stand that man, or his family, any more.

Nujood Ali got a divorce. It was the 15 April 2008. Her story is told in a book entitled “I am Nujood, age 10 and divorced” written by Nujood and the journalist Delphine Minoui.4

The book, distributed with huge success and translated into 17 languages, was made into a film by the director Khadija Al Salami, a victim herself – a former child bride – of an identical fate and a similar escape from a tyrant husband.

Nujood Ali’s story is personal and intensely narrated against the background of a rural environment in Yemen, similar to many other developing countries where the rights of girls and women are not recognised; where it seems that nobody pays any attention to the pain a little girl feels when, deprived of her childhood, her dreams, her plans for a happy life, she finds herself a prisoner of a man, in a house, a place, that all darken her very existence.

The book and the film on Nujood Ali are at the same time a warning and a journey of hope towards a better, freer, more humane and just society, without abuse and bullying at the expense of the weakest. A society open to total change to achieve the dream of many little girls: a society where everyone has rights. A society freed of poverty and the need to sell its own children.