Полная версия

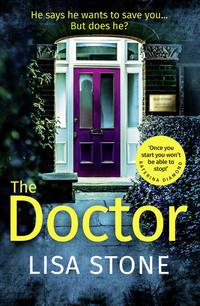

The Doctor

Amit assumed Robbie was their child and managed a polite smile.

‘Here we go,’ Emily said, reappearing and handing him the shoebox-sized package.

‘Thank you,’ he said stiffly. ‘I’m sorry you’ve been troubled again.’

‘No problem. How is Alisha?’ she asked.

‘As well as can be expected,’ he said tightly.

‘Please tell her I’d love to see her for coffee. If she isn’t up to coming here, I could pop in with Robbie.’

‘I’ll tell her,’ he said, with no intention of doing so. Saying goodbye, he returned down their drive and the front door closed behind him.

The irritation he felt at Emily’s bouncy cheerful personality was quickly replaced by excitement. He knew what the package contained: another vital piece of equipment. As soon as he’d had dinner, he’d go to his workshop and continue.

Half an hour later, leaving Alisha at the sink washing the dishes, Amit let himself out the back door, briefcase in hand and the package under his arm, and went down their garden path. The sun was setting now, elongating the shadows of the house and trees across the lawn. He preferred this time to the harsh light of day, which seemed to highlight flaws and imperfections. At the end of the path, he unlocked the padlock on his workshop, switched on the light and, going in, bolted the door behind him. No one could see him now. Blackout blinds were permanently down at all the windows, and he’d covered the glass in opaque film. It was pure luck the house had come with this substantial outbuilding, built by the previous owner as a recording studio. Already soundproofed, well insulated and with electricity running from the house, it hadn’t taken much for him to adapt it for its present purpose.

With a growing sense of pride and a little apprehension, Amit carefully took the bottle of anaesthetic from his briefcase. Opening one of the metal cabinets that stood against the wall, he placed the bottle on the top shelf with the other bottles of solutions. Drugs such as these were the only items he needed that couldn’t be bought legitimately from the internet as they required a special licence. Doubtless he could have bought them illegally, but there would be no guarantee they were pure and hadn’t been watered down or mixed with something to give the supplier more profit. The wrong or inferior drugs would be disastrous, and besides, no one at the hospital would notice the drugs were missing. As the anaesthetist, he was responsible for signing the drugs in and out of the operating room, and he took them one at a time.

Returning to the workbench, he slit open the package and took out the bag valve mask. It was in a sealed sterile package and was used for manually pumping air into a patient’s lungs. It would be crucial that Alisha’s brain received oxygen while he lowered her body temperature. He’d already bought a portable heart-machine. He’d use the manual pump as he transported her body from the house down the garden to his lab and then hook her up to the machine.

Retrieving a pen from the bench, he flicked through his list of essential items and ticked off the bag valve mask. He placed it in the cabinet on the second shelf. The shelves were nearly full now: bottles, tubing, scissors, forceps, scalpels, speculums, retractors, wound dressings, and so on. Items he would need to operate. Not a standard operation of course. He’d do what ELECT were doing: drain the blood from the body and replace it with preservation fluid. Then he’d store Alisha in liquid nitrogen at minus 190°C until a cure for her condition could be found. He’d be at the forefront of medical science, making a name for himself, and finally his parents would be proud of him.

Taking his laptop from his briefcase, Amit set it on his bench and perched on the stool. He brought up the bookmarked web page and ordered an aluminium tank large enough to hold a body. He’d been surprised at just how easy it had been to find what he needed online, partly due to the trend in cryotherapy – a treatment where otherwise healthy people paid to stand in a tank at minus 90°C for two minutes. It was being used to treat minor conditions, including sports injuries and skin conditions, as well as supposedly generating a feeling of youthfulness and well-being.

Having entered his card details to pay for the tank, he arranged a delivery date, then went to another website and ordered half a dozen white mice. He’d only get one chance with Alisha, so he’d practice the procedure on small animals first, until he was confident he had everything right, just as any reputable scientist would.

His mobile phone rang, making him start. He took it from his pocket and saw the call was from the house. It would be Alisha. Reliant on him, she phoned if she needed him urgently. Irritated at being interrupted, he pressed to accept the call.

‘What is it?’ he demanded.

‘I need your help quickly.

He sighed. He had to go. ‘I’m coming.’

Leaving everything as it was – he’d return later – he let himself out of his workshop.

The sun had set now and the lights were on in his and his neighbours’ houses, including Ben and Emily’s bedroom window. Emily was standing at the window looking out, watching him, as he’d seen her do before. His anger flared. Didn’t the nosy cow have anything better to do! Standing there brazenly. She must know he could see her. Drawing his head in, he hurried down the path to the back door. She needed to be careful, if she knew what was good for her.

Chapter Five

While the surgeon, Mr Barry Lowe, worked on his patient’s abdomen, Amit sat by her head and monitored her vital signs on the screen. Heart rate and rhythm, breathing, blood pressure, body temperature, oxygen level and body fluid balance were all normal. It was a relatively minor and straightforward procedure – an appendectomy – on an otherwise healthy thirty-year-old, so he didn’t envisage any problems. In operations like this, once the patient was under there was little for him to do but monitor the green and blue lines that ran across the screen.

Being an anaesthetist was a thankless job, he thought now as he often had before. Anaesthetists were at the bottom end of medicine. A branch you went into when you didn’t really want to be a doctor or didn’t make the grade. He’d been forced into medicine by his pushy parents who saw it as the gold-standard career. That or being a lawyer, which had appealed even less. Having a doctor or lawyer in the family gave his parents respect in their community, and he hadn’t had the guts to stand up to them. So with no calling to medicine or the law, and achieving poor grades at med school, he’d become an anaesthetist. Thankfully it involved very little contact with patients and required no bedside manner as they were unconscious, which suited him fine.

He watched Barry Lowe snip the infected appendix clear of the intestine and, with a sigh of satisfaction for a job well done, drop it into the stainless-steel bowl. He began closing the wound.

‘How’s your wife?’ he asked Amit, glancing at him over his surgical glasses.

‘As well as can be expected,’ Amit replied stiffly. ‘Thank you for asking.’ Those he worked with were vaguely aware Alisha had a life-limiting illness, but he’d never told them the details. He kept himself to himself and used Alisha’s illness as an excuse for not socializing with colleagues or attending hospital functions.

‘Did you ever get in any agency help?’ Barry Lowe asked, stitching the wound.

‘It’s not necessary,’ Amit replied. ‘She’s still able to look after herself. I can manage.’

‘Well, don’t get burnt out, we need you here,’ he said and put in the last stitch.

With the wound closed, Amit switched off the drugs that had kept the patient asleep and began the process of bringing her out of the anaesthetic. He turned down the nitrous oxide and turned up the oxygen. As expected, the patient’s facial muscles began to twitch as she started to regain consciousness. Then she gagged and he removed the endotracheal tube from her throat.

The operation over, the team began to dissemble. Barry Lowe removed his surgical gloves, dropped them in the bin and called goodbye as he left. The theatre nurses were clearing up, but, as usual, Amit stayed by the patient, monitoring her vital signs until she was responsive enough to speak.

‘Can you hear me?’ he asked her. ‘Your operation is over.’

‘Thank you,’ came her groggy reply.

Satisfied, Amit flexed his shoulders. They were always stiff, even after a short operation. His patient was ready for the recovery room and one of the theatre nurses would take her through soon. They were occupied at present, facing away from him as they cleared up and swabbed down after the operation. Quietly and quickly, in a smooth, well-practised movement, he slid the unused bottle of anaesthetic from the cart and tucked it into the pocket of his scrubs.

‘Thank you for your assistance,’ he said politely, moving away from the operating table. He always remembered to thank the theatre staff even if the surgeon forgot.

‘Goodbye, Dr Burman,’ the nurses returned.

The locker room was empty, good. Changing out of his scrubs, he transferred the bottle into his briefcase and headed for home where his true work awaited him.

Chapter Six

‘Well? What do you think?’ Emily asked Ben as soon as he came home from work. ‘Have I been busy or what?’ She led him to the patio doors.

‘You have been busy,’ Ben agreed. ‘You’ve done a good job, Em. It must have taken you ages.’

‘Most of the day. But it’s saved us having to pay a gardener. I enjoyed it. Robbie was with me, playing in the leaves. Now he’s toddling it’s so much easier to do stuff as he can amuse himself.’

‘Where is the little fellow?’ Ben asked, looking around.

‘In bed. He was exhausted. So am I. My arms are already aching from using the pruning shears. I’ve got muscles I didn’t know I had.’ She laughed. ‘Obviously I couldn’t trim the trees, they’re too high, but the hedge looks neater.’

‘It does. I hope Amit approves.’

‘What’s it got to do with him?’ Emily asked. ‘It’s our hedge and on our side of the fence.’

‘Whoa,’ Ben said, raising his hands in defence. ‘I just thought perhaps we should have mentioned it to him first. You really don’t like that bloke do you?’

‘Even less so now,’ she admitted. ‘While I was up the ladder trimming the top of the hedge, I could see over and into the living room. Alisha was standing at their living room window watching me. I waved and signalled for her to come out, but she shook her head. She looked like a scared rabbit, Ben. I’m not kidding. I’m sure it wasn’t that she didn’t want to come out but more that she daren’t. I think he could be abusing her.’

‘Oh come on, Em, just because you don’t like the guy doesn’t mean he’s a wife beater.’

‘Maybe not, but there was something in the way she stood there – like a trapped animal. I might have another go at asking her in. Anyway, glad you approve of my gardening. Let’s eat. The spag bol is ready. Can you dish up while I try to get Tibs in? She hasn’t been back all day.’

‘Will do,’ Ben said and kissed her cheek.

As Ben served dinner, Emily took the bag of cat treats from the cupboard. Opening the patio door, she called, ‘Tibs! Tibs!’ whilst shaking the bag. Usually by this time of day Tibs was home and wanting her dinner, but if not, then hearing the bag of treats brought her running from whichever garden she was in. ‘Tibs, Tibby,’ Emily called again, rattling the bag of treats, but there was no sign of her. ‘I’ll try again later,’ she said at last. Closing the patio door, she took her place at the dining table. ‘It’s not like her. I wonder if she’s got shut in somewhere. If she’s not back by tomorrow, I’ll knock on some of our neighbours’ doors and ask them to check their sheds and garages.’

‘I’m sure she’s fine,’ Ben said. ‘It’s a dry evening. She’ll be off hunting.’

‘Tibs! Tibby!’ Emily called repeatedly at 9.30 p.m. She was outside now, standing on the patio and shaking the bag of treats. ‘Tibs!’ She paused and listened for any sound suggesting Tibs had heard and was starting her journey home. Sometimes when she strayed a long way she could hear her in the distance. The foliage stirring, her claws scraping as she clambered over wooden fences, going from garden to garden. Then, when she entered her own garden and saw Emily, she meowed loudly. But now the air remained still and eerily quiet, a clear November night, with a waxing moon rising in a cloudless sky.

Emily tried once more before she went to bed at 11 p.m. This time she put on her coat and went right down to the bottom of the garden, calling ‘Tibs, Tibby!’ The light in the outbuilding next door was on and with the hedge lower now she could see the top of the windows. As usual, the door was closed and the blinds were down, but even if they hadn’t been it would have been impossible to see in for the film covering the glass. She had watched Amit stick it on about six months ago when he’d started using the building every evening and most weekends. What he did in there, she’d no idea, but if Tibs wasn’t back in the morning, she’d ask him or his wife to check it and their garage for Tibs, although she doubted she was in there. Amit didn’t hide the fact he hated cats. She’d heard him throwing stones at Tibs when she’d strayed into his garden – one of the reasons she didn’t like the man. She’d read somewhere that people who were cruel to animals were invariably cruel to people too.

‘Tibs! Tibs!’ she called again. Giving the bag of treats a final good shake, she admitted defeat and returned indoors. All she could do now was leave the cat flap open and hope that Tibs found her way back during the night.

‘We’re going to find Tibs,’ she told Robbie the following morning as she zipped him into his snowsuit. ‘She hasn’t come home. I think she’s lost or got shut in somewhere.’ The alternative – that she’d been run over – she pushed from her mind.

Robbie babbled baby talk and tried to say Tibs.

‘Yes, that’s right. Tibs. Good boy.’

Strapping him into his pushchair, she then tucked her phone, keys and the missing cat leaflets she’d printed into her coat pocket and left the house. It was mid-morning and she knew many of the houses would be empty, with their occupants at work. If there was no reply, she’d push one of the leaflets through their letter box. It had a picture of Tibs and gave her address, telephone number and asked them to check their shed, garage and any outbuilding in case she’d been shut in. It was of some consolation that Tibs had been microchipped and Emily’s mobile phone number was engraved on a metal disc on her collar, so if someone found her dead or alive they would hopefully contact her. However, it was also possible, Emily thought, that Tibs had been lured into a home with food and hadn’t wanted to leave. Cats were renowned for cupboard love. But when they let her out for a run, she’d return home.

‘Tibs,’ Robbie gurgled again.

Emily approached the task methodically and began with the house to the left of theirs. She knew the family would be at work, so she pushed one of the ‘missing cat’ leaflets through their letter box. She continued to the next house and worked her way up the street, crossed over at the end and began back down the other side. It was time-consuming, but those who were in were generally sympathetic. Some invited her in to check their garage or shed, others said they’d check as soon as she’d gone and hoped she found Tibs soon. The Burmans’ house was the last and by now Robbie had grown restless, having had enough of sitting in his pushchair. ‘Soon be home,’ Emily reassured him and gave him a leaflet to hold.

It was only after she’d unlatched their gate and began up their path, giving her a clear view of the house, that she saw it.

‘Bloody hell!’ she said out loud. All the windows at the front of the Burmans’ house were now covered with the same opaque film Amit had used on the windows of his outbuilding. He must have done it last night after she’d cut the hedges, for it hadn’t been there yesterday. Although she’d cut the front hedge as well as the back, it still offered them privacy. The man was obsessed, she thought. Had he done the same to the windows at the back of the house? Surely not?

Robbie agitated again, squirming to get out.

‘Last house,’ she told him.

Glancing up at the CCTV, she pressed the bell on the entry system, then began folding one of the missing cat leaflets ready to push through their letter box. She doubted Alisha would answer the door; she hadn’t for a long while. Robbie grumbled and struggled to get out, then to Emily’s amazement, she heard a noise on the other side of the door and a key turn in the lock.

‘Alisha, how nice to see you. How are you?’ she asked, barely able to hide her surprise.

‘I’m not bad, thank you.’ She looked very thin and pale and had dark circles under her eyes, but she managed a small smile.

‘I’m sorry to disturb you, but have you seen our cat, Tibs? She’s been missing for twenty-four hours.’

‘No, I haven’t. But I’ll ask Amit when he comes home tonight.’

‘Thank you. Can you ask him to check your garage and that outbuilding in your garden in case she’s got shut in?

‘Yes, of course.’ She didn’t immediately start to close the door as she had done before.

‘Your husband has certainly gone to town on your windows,’ Emily couldn’t resist commenting. ‘Is that because I trimmed the hedges?’

Alisha nodded, embarrassed. ‘Amit worries about security with me in the house all day. We were broken into where we lived before.’

‘Oh, I see. I’m sorry,’ Emily said and felt slightly guilty. ‘Has he done the back windows as well?’

‘Yes, even the upstairs. I’ve told him we’re safe here, it’s a nice neighbourhood. But when he gets an idea into his head he won’t listen to reason and there’s no stopping him.’ It was the most Alisha had ever said to her, Emily thought.

‘I understand,’ Emily said. Robbie began whinging. ‘I’ve got to go now, but won’t you come in for a coffee? I know I’ve asked you before, but I would really like it if you did.’

Alisha hesitated but didn’t refuse outright. ‘It’s difficult. Amit wouldn’t like it. He worries about me.’

‘Does he have to know?’ Emily asked. ‘I mean, I’m not suggesting you lie, but couldn’t you just pop round while he’s at work? Or I could come to you?’

‘No, it’s better if I visit you,’ Alisha said quietly. ‘But I can’t stay for long.’

‘That’s fine. Stay as long as you like. I’m free tomorrow afternoon.’

‘OK. I’ll try to come at one-thirty.’

‘Great. See you then.’

And although Tibs hadn’t been found yet, Emily went away feeling she had achieved something very positive indeed.

Chapter Seven

That night, Amit sat at the workbench in his lab and looked dejectedly at the dead rat; its pink eyes bulging and its mouth fixed open in a rigor mortis snarl. He couldn’t understand why it and the mice had died. He’d only stopped its heart for fifteen minutes, during which time it had been submerged in ice. Animals and humans had survived much longer than that after accidentally falling into icy water; their hearts stopping as they entered a state of suspended animation and then restarting once resuscitated. In one case, a child had been brought back after being submerged in a freezing lake for two hours with no ill effect, so why couldn’t he replicate that here?

He threw the rat into the bin with the others and dug his hands into the pockets of his white lab coat. He stared at the remaining two rats in the cage. Perhaps there was a genetic weakness in the rats and the mice he’d bought, for doubtless they’d been interbred. Yet the other animals he’d tried the procedure on had all gone the same way. He knew from a science journal that dogs in a lab had been brought back to life after three hours following this process, so what on earth was he doing wrong?

Resting his head in his hands, Amit studied his notes and calculations, then opened the cage door and took out one of the remaining rats. It squirmed and squeaked as if sensing its fate. He placed it on the bench beside the syringe that was ready with the solution and held it down firmly. He’d try a smaller dose this time – see if that made any difference. Then he suddenly stopped and looked up, deep in thought.

He’d been stopping their hearts artificially, but of course when a person or animal fell into icy water, their heart was still beating as they went under and suspended animation occurred. Patients who were going to be preserved for cryonics treatment were put on a heart-lung machine until they could be submerged in ice, so they too were technically alive. Was that the answer? Something so simple: the subject’s heart had to still be beating. At what point the heart-lung machine was switched off, he didn’t know. It wasn’t a detail ELECT made public. But it was possible it wasn’t switched off until the person was frozen, so they were frozen alive, although unconscious. Could that really be the solution? If he froze the rat while its heart was beating would that allow him to bring it back from the dead?

Amit temporarily returned the rat to its cage while he took a bottle of anaesthetic from the top shelf of the cabinet and drew some into a syringe. It was the anaesthetic he used on his patients at the hospital and would keep the rat asleep while maintaining its vital signs. He would only need a drip or two as the rat’s body was a fraction of the size of a human’s. If this worked, he’d try the process on larger animals, just as scientists did in lab experiments, before he attempted it on a human.

Opening the cage, he picked up one of the rats – the other squeaked in protest at losing its mate – and set it on the workbench. Holding it firmly by the scruff of its neck, he injected the anaesthetic. Almost immediately, the rat’s eyes closed and it relaxed, unconscious, on the bench. Taking his stethoscope, he listened to its heartbeat and then placed it into the ice bath and began monitoring its temperature. Normal body temperature for a rat was 37°C, the same as for humans. It quickly plummeted to 30°C, 24°C, and then down to 20°C. Circulatory arrest happened at 18°C and its heart stopped beating. The rat’s temperature continued to drop to zero and further still. When it reached minus 90°C, following the procedure used at ELECT, Amit took a scalpel and made a small incision into the rat’s jugular vein and drained off half its blood into a bottle. He then injected preservation fluid into the vein – the same solution used for preserving organs for transplant – and returned the rat to the ice bath.

He felt hot, clammy and anxious, for despite carrying out similar procedures before, if he failed now he’d made the adjustment he’d no idea what else he could do. Failure wasn’t an option.

The rat’s temperature continued to fall down to minus 130°C. It was at this point in the cryonics procedure the body was lowered into the tank of liquid nitrogen and stored at minus 195°C. But Amit waited five minutes and began to reverse the process, gradually raising the rat’s temperature and then returning its blood. At 37°C he tentatively placed his stethoscope on the rat’s chest and listened for any sign of a heartbeat. Nothing. Not the faintest murmur. He massaged the rat’s chest, hoping to stimulate its heart, and listened again. Still nothing. It had gone the same way as all the others! Whatever was he doing wrong?

He stared at the lifeless body of the rat and was about to give up and throw it in the bin when he thought he saw one of its toes twitch. Returning his stethoscope to its chest, he listened hard, his breath coming fast and low. It wasn’t his imagination! He could hear the very faintest murmur of a heartbeat. He massaged the rat’s chest again and listened. Yes, there it was, stronger now. The irregular beats joining to form a steady rhythm. Then the rat gasped its first breath. He’d done it! He’d really done it. He could barely contain his excitement.