Полная версия

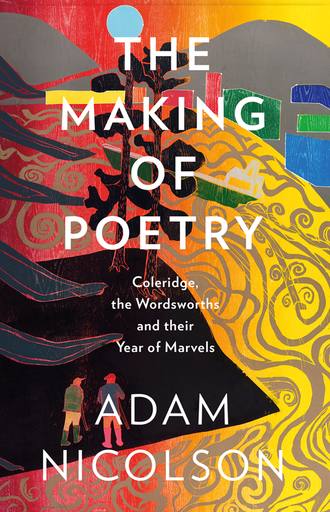

The Making of Poetry: Coleridge, the Wordsworths and Their Year of Marvels

After he had left university, with no good degree, he went to London, directionless and unfocused, unable to commit to any life in the Church, the law, university, politics or commerce. He felt ‘rotted’:

my life became

A floating island, an amphibious thing

Unsound, of spungy texture.

But the scent of liberty was coming across the Channel. A decade earlier, the Americans had cast themselves free. Now an ancient European monarchy was heading for a rational, liberated future. Richard Price, a suddenly famous dissenting minister-turned-lecturer, was drawing vast crowds to his London talks. ‘A general amendment’, he told his excited audience, was beginning in human affairs:

the dominion of kings [is] changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priests giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience. Be encouraged, all ye friends of freedom, and writers in its defence!

Once again, Wordsworth was drawn to France, not only to escape the urgings of his relatives, who had in mind a rural curacy, but to taste and know the sources of the future. This time he went to the Loire valley, where, even as the massacres were committed in Paris and the French Republic was being declared, he met two people who had a shaping influence on his life and thought. The first was an officer in the army, Armand-Michel Bacharetie de Beaupuy, known simply as Michel Beaupuy, an aristocrat from the Périgord, now in his mid-thirties, and a republican idealist, who in Wordsworth’s loving remembering of him in The Prelude sounds like a vision of the perfect man. They talked politics and the virtues of change, weighing the best of ancient republican systems against the extremes of revolutionary violence, sifting what seemed good from the horrors and strains of the moment.

Injuries

Made him more gracious, and his nature then

Did breathe its sweetness out most sensibly,

As aromatic flowers on Alpine turf,

When foot hath crushed them.

By birth he ranked

With the most noble, but unto the poor

Among mankind he was in service bound,

As by some tie invisible, oaths professed

To a religious order. Man he loved

As man, and, to the mean and the obscure,

And all the homely in their homely works,

Transferred a courtesy which had no air

Of condescension; but did rather seem

A passion and a gallantry, like that

Which he, a soldier, in his idler day

Had paid to woman: somewhat vain he was,

Or seemed so – yet it was not vanity,

But fondness, and a kind of radiant joy

That covered him about when he was intent

On works of love or freedom.

Beaupuy looked like an oasis in a bitter world, a source of hope and goodness in a violent time, a demonstration that human nature was capable of fineness and grace. With him, walking along the road in Touraine, Wordsworth had a sudden, formative encounter, one of those spots of time that make us what we are, remembered for the rest of his life:

And when we chanced

One day to meet a hunger-bitten girl,

Who crept along fitting her languid self

Unto a heifer’s motion – by a cord

Tied to her arm, and picking thus from the lane

Its sustenance, while the girl with her two hands

Was busy knitting in a heartless mood

Of solitude – and at the sight my friend

In agitation said, ‘’Tis against that

That we are fighting,’ I with him believed

Devoutly that a spirit was abroad

Which could not be withstood, that poverty,

At least like this, would in a little time

Be found no more, that we should see the earth

Unthwarted in her wish to recompense

The industrious, and the lowly child of toil,

All institutes for ever blotted out

That legalized exclusion, empty pomp

Abolished, sensual state and cruel power

Whether by edict of the one or few –

And finally, as sum and crown of all,

Should see the people having a strong hand

In making their own laws; whence better days

To all mankind.

It is difficult to judge how much The Prelude attributes later thoughts and ideas to earlier events – Wordsworth was imperious in his relationship to time – but that moment with Beaupuy, who in 1796 would be killed by a cannonball in battle against the Austrians, and the simplicity and passion of the remembered words, ‘’Tis against that/That we are fighting,’ seem now to stand as one of the sources of Wordsworth’s later life. Beaupuy’s name is among those cut into the stones of the Arc de Triomphe, but these lines, in which he is described in the beautiful, supple, easy blank verse of The Prelude, are a true memorial.

At the same time, Wordsworth fell in love with a young French woman. Annette Vallon was four years older than him. Their story, which was only ever known within the family circle in Wordsworth’s lifetime, is exceptionally opaque. She was the daughter of a surgeon in Blois. Nearly nothing is known about her, except that during the years of the Revolutionary wars, in which her Catholic and Royalist family suffered at the hands of the Republic, she and her sisters behaved with extraordinary and resourceful courage, running messages for the Royalists, concealing enemies of the state, smuggling them to safety, evading the secret police, in turn, of the Terror, the Directoire and Napoleon, risking all. Wordsworth had fallen in love with a woman of mettle and fire. She had first encountered him late in 1791, at the house in Orléans of André-Augustin Dufour, a magistrate’s clerk, and may have begun by teaching him French, but soon they moved together to Blois. In the spring of 1792 she became pregnant with their child.

Wordsworth scarcely communicated with anyone at home, only asking his brother Richard for some money, but saying nothing of Annette. In December 1792 their daughter, Anne-Caroline Vallon, was born and baptised in Orléans, the French clerk carefully recording the impossible name ‘Anne Caroline Wordswodsth, daughter of Williams Wordswodsth, Anglois, and of Marie Anne Vallon’. Wordsworth had made arrangements for Dufour to represent him at the baptism, by which time he himself had gone, leaving Annette unmarried and unsupported. Astonishingly, he did not return immediately to England, but spent six weeks in Paris witnessing the drama of revolution.

It is, at the least, chaotic behaviour. Although their politics were directly opposed, Annette certainly expected him to marry her. She called herself Annette Williams, and her distraught letters long for his return, for him to be present in her life and the life of their daughter. Only obliquely did Wordsworth ever write of her, as an interlude in The Prelude, in which there is no suggestion that the love affair he describes was anything more than a story told to him by Beaupuy. But it is filled with memories of the ‘delirious hour’, the ‘happy time of youthful lovers’ he had known with her, the promise of that Loire valley beginning:

his present mind

was under fascination; he beheld

A vision, and he lov’d the thing he saw.

Arabian fiction never fill’d the world

With half the wonders that were wrought for him.

Earth liv’d in one great presence of the spring …

all paradise

Could by the simple opening of a door

Let itself in upon him, pathways, walks

Swarm’d with enchantment, till his spirit sank

Beneath the burthen, overbless’d for life.

It may be that, at the height of the reign of Terror late in 1793, with Britain at war with France, Wordsworth quickly and secretly returned to see her – there are suggestions of that in The Prelude – but he was soon gone, and her piteous letters resumed:

Come, my friend, my husband, receive the tender kisses of your wife, of your daughter. She is so pretty, this poor little one, so pretty that the tenderness I feel for her would drive me mad if I didn’t always hold her in my arms. She looks like you more and more each day. I believe that I hold you in my arms. Her little heart beats against mine and I feel as if it is your heart beating against me. ‘Caroline, in a month, in a fortnight, in a week, you will see the most cherished of men, the tenderest of men’ … Always love your little daughter and your Annette, who kisses you a thousand times on the mouth, on the eyes … I will write to you on Sunday. Goodbye, I love you for life. Speak to me of the war, what you think of it, because it worries me so much.

Wordsworth never received that particular letter, as it was impounded by the Committee of Surveillance, and was only discovered in the 1920s, with one other, hidden in the files of a sub-police station in the Loire valley. But others of the same kind, all now destroyed, crossed the Channel, filled with appeals to a desperate conscience.

On his return to London, Wordsworth sank into the deepest depression of his life, besieged by guilt and ‘dead to deeper hope’, his soul dropping to its ‘last and lowest ebb’. He had lost all faith in human endeavour. His abandonment of Annette and Caroline was fused in his mind with the fate of the Revolution in France and the turn to repression in England, with his own lack of any future and the absence of much hope for the ideals Beaupuy had embraced and the happiness Annette may have represented.

Wordsworth wandered lost through these years. After 1793 France was at war with England, and Wordsworth, in love with liberty and in love with his own country, found himself torn in two. He moved from place to place – Wales, Yorkshire, the Isle of Wight, Salisbury Plain, London, Westmorland, Cambridge – without employment, without prospects, without money, without love, almost without friends, living sometimes in London, mixing in the circles around the rationalist republican William Godwin, involved with radical politics, writing at least one long attack on the Church and the establishment, sometimes in the north of England, occasionally reunited with his adoring sister Dorothy, just as often apart from her.

His depression was accompanied by radical, republican rage. Compassion, he wrote, was to be done away with. Liberty was to ‘borrow the very arms of despotism’, and ‘in order to reign in peace must establish herself by violence’. The contempt with which the Wordsworth family had been treated by the Earl of Lonsdale fuelled his hatred:

We are taught from infancy that we were born in a state of inferiority to our oppressors, that they were sent into the world to scourge and we to be scourged.

The British government was bent on suppressing the French contagion. In May 1794 Habeas Corpus was suspended and dozens of radicals were arrested. The following year seditious gatherings and pamphlets were banned. Free speech was gagged. Many writers, printers, publishers, booksellers and lecturers who had embraced the radical ideas of their generation were placed in the pillory, imprisoned for six months or more, harassed, interrogated, ruined or transported to Australia, from where few would ever return. Others were tried for treason or condemned to death in their absence. In these conditions, Wordsworth’s tirades were too extreme for any printer to risk their publication, and he remained almost unknown.

Wordsworth in Darkness

Through connections of the Godwin circle he met the Pinneys, whose house at Racedown was offered to Wordsworth brother and sister as a place of refuge away from the stress and strain of the city, from the stress and strain of his own mind.

In September 1795, Dorothy and William retreated to Dorset, taking with them little Basil Montagu, the son of a young lawyer also called Basil Montagu, whose wife had died in childbirth and who was struggling to bring up his son in his chambers in Lincoln’s Inn. The Wordsworths had the hope that other children might join them to make a little school at Racedown, whose fees they could add to the income from the investment of the legacy.

Darkness gathered around Wordsworth, although neither he nor his sister could admit as much in their letters. A disenchantment with political radicalism and its rationalist revolution had left him with a sense of having nowhere to go. He was afflicted with debilitating headaches. His nightmares of the Terror, as he would later tell Coleridge in The Prelude, had come with him:

I scarcely had one night of quiet sleep,

Such ghastly visions had I of despair

And tyranny, and implements of death,

And long orations which in dreams I pleaded

Before unjust Tribunals, with a voice

Labouring, a brain confounded, and a sense

Of treachery and desertion in the place

The holiest that I knew of, my own soul.

The sense of treachery and desertion was all-colonising: a betrayal of his own ideals, of the hope that had once glowed in France, of his youth, of his child, of her mother, of himself. It was an amalgam of fear and guilt. Wordsworth felt disconnected from the goings on of life and the world. He asked for newspapers to be sent to him, no matter if they were five days old by the time they arrived. He thought of himself as ‘a man in the moon’ who had no inkling of what was happening on earth. Coleridge would later describe Wordsworth’s ‘unseeking manners’, that drift towards isolation, the refusal to engage with anyone or anything beyond himself. A kind of sardonic humour seeped out of him. ‘Our present life is utterly barren of such events as merit even the short-lived chronicle of an accidental letter,’ Wordsworth wrote to his Cambridge friend William Mathews, now a bookseller in London.

We plant cabbages, and if retirement, in its full perfection, be as powerful in working transformation on one of Ovid’s Gods, you may perhaps suspect that into cabbages we shall be transformed.

He had heard that remarks of that sort were circulating in London. ‘As to writing, it is out of the question.’

Cynicism and bitterness, a dark estimation of himself and others: these were the outlines of a Wordsworth lost. ‘We are now at Racedown and both as happy as people can be who live in perfect solitude,’ he wrote to Mathews.

We do not see a soul. Now and then we meet a miserable peasant in the road or an accidental traveller. The country people here are wretchedly poor; ignorant and overwhelmed with every vice that usually attends ignorance in that class, viz – lying and picking and stealing &c &c

He had sunk inward, in a kind of paralysis, held in uncertainty and perplexity, not bounding down the flank of a wheatfield but stalled at the gate, balked and blocked. It was, he later wrote, ‘a weary labyrinth’. He turned to bitter satire, imitating Juvenal, in which with ‘knife in hand’ his aim was to ‘probe/The living body of society/Even to the heart’.

He made visits to London and Bristol, and on one of them, probably through the Pinneys, he met Coleridge and began to show him and send him the poetry he was writing. Coleridge’s letters to him from that time have disappeared, but through the course of 1796 it seems as if, perhaps under Coleridge’s habit of encouragement, Wordsworth began to emerge from the darkness, and to feel his powers returning as both a man and a poet.

Pieces survive in his notebooks from that year, never shown to anyone, in a form of almost undecorated poetry, never published, surviving only as fragments of rough manuscript on the back of sheets containing other lines. One describes an incident on the road outside Racedown, a transient scene reminiscent of the encounter with the poor girl with the heifer in the Loire valley five years before. A baker from Clapton, just outside Crewkerne, used to deliver to houses in the area, and regularly came past Racedown. The speaker begins by addressing a young woman he has met in the road:

I have seen the Baker’s horse

As he had been accustomed at your door

Stop with the loaded wain, when o’er his head

Smack went the whip, and you were left, as if

You were not born to live, or there had been

No bread in all the land. Five little ones,

They at the rumbling of the distant wheels

Had all come forth, and, ere the grove of birch

Concealed the wain, into their wretched hut

They all return’d. While in the road I stood

Pursuing with involuntary look

The Wain now seen no longer, to my side

came, pitcher in her hand

Filled from the spring; she saw what way my eyes

Were turn’d, and in a low and fearful voice

She said – that wagon does not care for us –

That wagon does not care for us. This is unfinished: he addresses the woman, but then describes to her the scene she would just have witnessed herself. She begins by standing next to her hut, but then arrives from the spring with her pitcher. Nor can he name her – Wordsworth left a blank at the beginning of the line. But in its under-qualities, its directness and the simplicity of its language, its rhymeless pentameters without an abstract noun or any large Miltonic reference to the important or the exotic, one part of what would happen this year is already underway. This is the first signpost towards Wordsworth’s future as a poet. The truth of her statement – that wagon does not care for us – emerges from under the carapace of the brutalised-civilised. It seems as if poetry, allied to the language of the real, can do what politics and revolution can never manage: make vivid and present the reality of suffering, of human experience, for which no exaggerated language or theatrics are required.

No graph of a life pursues a single line, and the man Coleridge had come to see and be with, to admire and encourage, is a hazy compound of mentalities and influences. With his hair cut short in the republican manner, and a heavy stubble on his cheek, there was an intense, haunted and self-possessed air to him. The artist Benjamin Robert Haydon later said that there was something ‘lecherous, animal & devouring’ in Wordsworth’s laugh, and there is no doubt of the almost predatory power that hung about him. He would always control anyone who came into his orbit. And his erotic life was real and vivid. When, later, after ten years of marriage, he was away from his wife for a few days, he wrote to her: ‘I tremble with sensations that almost overpower me,’ his mind filled with images and memories of ‘thy limbs as they are stretched upon the soft earth’ and ‘thy own involuntary sighs and ejaculations’.

The writing of poetry could take hold of him in what he called ‘the fit’, the need to get it down before it left his mind. His sister Dorothy watched him one morning at breakfast:

he, with his Basin of Broth before him untouched & a little plate of Bread & butter.

He had not slept well, but the idea of a poem had come to him.

He ate not a morsel, nor put on his stockings but sate with his shirt neck unbuttoned, & his waistcoat open while he did it. The thought first came upon him as we were talking about the pleasure we both always feel at the sight of a Butterfly. I told him that I used to chase them a little, but I was afraid of brushing the dust off their wings, & did not catch them – He told me how they used to kill all the white ones when he went to school because they were Frenchmen …

Uniforms in the armies of Bourbon France had been white, decorated with golden fleur-de-lis, and any right-thinking English boy in the 1770s would have pursued them with a vengeance. Wordsworth was remembering that from the other side of a revolution that had replaced the white with the tri-colour, but in this tiny scene, away from public view or the need to present himself as he might have wanted to be known, something of the undressed Wordsworth appears: quietly and gently witty, preoccupied, getting up late, needing to catch the moment of writing a poem before it fled, his memories and the present moment interacting as two dimensions of one life, calmly there in the room but, in the writing of that poem, entirely removed, alone.

One further element reflects on Wordsworth in the late 1790s. In the archive at Dove Cottage in Westmorland is the extraordinary and rare survival of some of his clothes. His waistcoats and breeches from the last years of the eighteenth century open a shutter on to this gentleman-poet, governor-radical, man of the people who was also a man, in his own mind, set far above them. Much of the poetry he would write this year was intended, as he said, ‘to shew that men who did not wear fine cloaths can feel deeply’, and one might imagine that a poet who wrote those words might also wear the fustian and the grosgrain of the working man.

He did not. In Grasmere you can find his cream waistcoat with linen back and silk front, with a kind of spreading collar and decorated with embroidered flowers, its pockets edged with red braid, its twelve fabric-covered metal buttons each decorated with a flower. Beside it is a matching suit of waistcoat and breeches also in cream silk, this waistcoat with a stand-up collar, two small pockets with scallop-edged flaps, and eleven small buttons covered in fabric. The breeches are knee-length, gathered into a band at the knee and secured by four fabric-covered buttons and a strap fastening. A third waistcoat is in ivory silk, decorated in careful pale-blue, red and white embroidery, scattering his chest and stomach with perfect, crystalline lilies of the valley.

Are these really the clothes of the man who would write The Prelude? Was Wordsworth a dandy? In Germany late in 1798, according to his sister, he went out ‘walking by moonlight in his fur gown and a black fur cap in which he looks like any grand Signior’. The gown was green, ‘lined throughout with Fox’s skin’. At other moments he would appear in ‘a blue spencer’, a short double-breasted overcoat without tails, and a new pair of pantaloons. Perhaps one can see in this elegance and this air of distinction, this distance from mud and toil, a picture of the man who was living in Racedown and considering his position as an un-acknowledged legislator of the world, preparing to convey to that world his vision of completeness and authority. ‘The Poet binds together by passion and knowledge the vast empire of human society, as it is spread over the whole earth …’, he would write a year or two later. There is no retreat in those magnificent words to a cosy provincial irrelevance. The ambition is explicitly imperial. Here is a man who wanted to establish a form of poetry whose ligatures would bind up the whole of existence.

His sister Dorothy, part-hidden, is at the centre of this year. There is a surviving silhouette of her: small and bright, sharp, attentive, slight-bodied. Her hair is bound up, her whole being taut. A high lace collar, curly hair on her brow. Delicate, poised, a small bosom, half-open lips, drawn in this silhouette with all the expectations of femininity, her presence almost toylike, but nothing skittish or girlish: careful, exact, intelligent, enquiring.

Coleridge described her in a letter written a few weeks after he had arrived at Racedown:

Wordsworth & his exquisite Sister are with me – She is a woman indeed! – in mind, I mean, & heart – for her person is such, that if you expected to see a pretty woman, you would think her ordinary – if you expected to find an ordinary woman, you would think her pretty! – But her manners are simple, ardent, impressive –

Above all they noticed each other’s eyes. Hers were ‘watchful in minutest observation of nature – and her taste a perfect electrometer – it bends, protrudes, and draws in, at subtlest beauties & most recondite faults’. His were large and grey, lit and sparkling when animated, sometimes half-absent, as if he had sunk a quarter of an inch below the surface of the skin, but otherwise rolling bright towards you, as if the sight within them were not a receptive faculty but active, coming and reaching out to grasp his hearers. The lower part of his face could look somehow unbuttoned. His mouth was always hanging half open – he couldn’t breathe through his nose. ‘I have the brow of an angel, and the mouth of a beast,’ he used to say, the repeated binary vision of himself, great and weak, good and bad, never ceasing to oscillate between its poles.