Полная версия

The Hidden World of the Fox

That birthplace was North America; perhaps dogs are the United States’ most successful export. Canids have spent the majority of their evolutionary history restricted to this one continent, and the distant ancestors of foxes are dated to the Eocene jungles of Texas. Prohesperocyon – the first known canid – was a small, omnivorous creature in a forest of astonishing giants, a natural neighbour to the likes of the fearsome Nimravidae, sabre-toothed carnivores resembling great cats. As Earth gradually cooled and dried and the dense jungles were replaced by extensive grasslands, the elongated legs and long strides of the canid body shape clearly provided an advantage in long distance chases. Canidae thrived.

Most of the fox’s extended family is extinct, and known to us only through palaeontology, but the glimpses defy imagination. Among them is the subfamily Borophaginae, containing species that might frighten Cerberus – they were the bone-cracking dogs, with massive teeth capable of extracting marrow from giant carcasses. Epicyon haydeni, the largest of all, is estimated to have weighed four times as much as an average grey wolf, and a pack on the hunt must have been a formidable sight. Yet the dentition of many fossil canids, not least the little Leptocyon – the direct ancestor of the fox – strongly suggests a varied, plant-inclusive diet.

Plate tectonics and the reduction in sea levels during ice ages eventually connected North America to other continents, and its wildlife migrated into South America and Eurasia. By seven million years ago, at least one canid was present in Spain, and Vulpes riffautae – the earliest known fox outside North America – lived in what is now the N’Djamena desert in northwest Chad. Fast forward another few million years, and Vulpes galaticus is part of the Turkish fauna. Vulpes vulpes, the red fox – the only species that we have in modern Britain – is recorded first in Hungary, perhaps 3.4 million years ago, when humans in Africa were just beginning to use stone tools. Recent genetic analysis has provided further hints; it appears that all living red foxes are descended from individuals who lived in the ancient Middle East. From there, they spread across the entire northern hemisphere.

Canids travel. Their long legs and unfussy diets enable them to colonise new habitats with ease. Nature is not a fixed condition, and Britain has experienced many waves of colonisation and extinction over its geological history. But from the perspective of a wild animal, one of the most significant qualities of our island is that it lies rather far to the north. Much as we complain about the weather, it is remarkably mild for a country on the same latitude as Moscow. Take away the Gulf Stream, and it would be time to buy some serious winter clothing. Add all the geographical and solar phenomena which regularly cause the world to have ice ages, and the Thames Valley becomes cold, hard tundra.

I have tried to breathe normally in temperatures of -35°C (-31°F), on a day in Alberta when humans seemed disinclined to be outside. Gulping such air is like swallowing swords; your lungs baulk at the freezing blast, yet it is nothing compared to the frigid temperatures reached in the wind-chill from a continent-wide ice sheet several kilometres thick. The Pleistocene Epoch played a long game of catch-and-release with Britain, repeatedly coating the northern half of the country with dense ice and then releasing it in warm interludes called interglacials. We live in an interglacial now called the Holocene. It has lasted nearly 12,000 years, but it probably won’t continue forever.

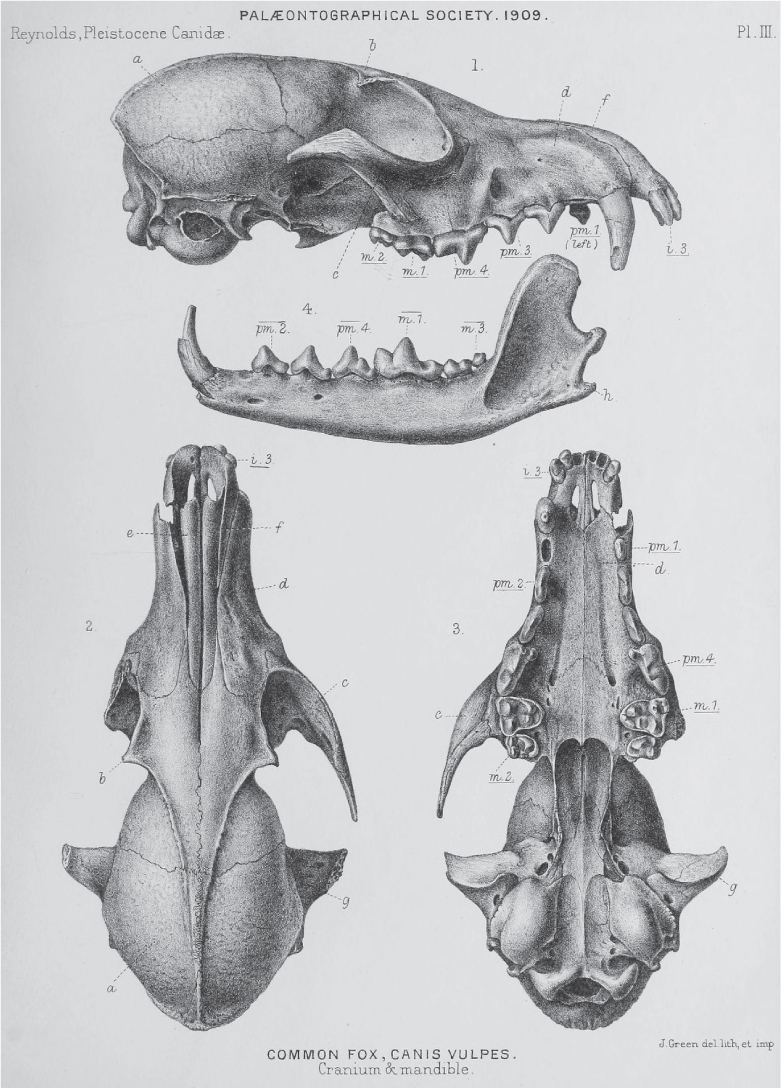

© Red fox skulls and jaw and jaws from Ightham Fissure, near Maidstone. Plate III in Sidney H. Reynolds, A Monograph of the British Pleistocene Mammalia. Vol. II, Part III: The Canidae, London, 1909 (Wikimedia Commons)

A study of red fox bones. This one lived during the Pleistocene in what is now Kent.

Our wildlife has been dictated by ice. The fossil record suggests that red foxes appear in the interglacials, historically alongside a wealth of other creatures that would monopolise attention if glimpsed on safari in Africa. Our first British foxes perhaps scavenged on the carcass of a straight-tusked elephant predated by cave lions, and certainly would have heard the whooping laughs of spotted hyena. The next time you wonder why a fox sits and watches you rather than bolting in panic, remember they have had to judge the risk from very dangerous predators for thousands of millennia, and their evolved strategy is waiting at a safe distance with access to a known safe spot, such as a den or – these days – a gap in a fence. If they had run further than required from each Pleistocene sabre-toothed cat, European jaguar and cave bear, the energy wastage would have crippled them.

Meanwhile, Arctic foxes – along with woolly mammoths, wild horses and reindeer – were present during the colder times. Red foxes disappeared from Britain entirely, surviving in the relatively mild refugia in Spain and the Balkans. Sometimes, while walking in my native Surrey Hills, I try to imagine what those glacial millennia must have been like. The glaciers never extended this far south, but the bite from the wind must have been excruciatingly bitter, and the landscape would have been an austere mixture of bare rock and frozen snow. Fed by the ice sheet were huge rivers of cyan-blue glacial meltwater.

And foxes must have drunk from them. But were they the Arctic or red species?

Over in Somerset, one cave dated to 12,000 years ago contains fossils of both, but red foxes have always returned north and displaced their smaller Arctic cousins in times of mild climate, and they continue to do so on the modern thawing-line of Sweden. In any case, while lions and hyenas did not migrate back to Britain after the ice retreated, foxes rapidly did, even as tundra budded with crowberry bushes and mugwort, and finally grew trees once more.

SO THE FOX trotting across a Clapham street is directly descended from individuals that encountered species wondrous beyond our most outlandish fairy stories, survived extremes of climate that we have never known, and crossed land bridges long lost beneath the sea. Human culture is such a late entry into the story of the fox that it would seem disingenuous to mention it – except, of course, we have a strong bias towards it.

No one will ever know where the first Homo sapiens laid eyes upon a living fox, or how the two species perceived each other. As pre-history continues, our fossils and theirs begin to overlap in palaeontological sites, a silent testimony to forest meetings that have passed into the veil of unwritten time. But 16,000 years ago, when Palaeolithic painters were drawing steppe bison in the Spanish cave of Altamira, a woman of unknown name died in what is now Jordan, in a site called ‘Uyun al-Hammam. Her body was laid among flint and ground stone, and a red fox was carefully placed beside her ribs, resting with her for eternity on a bed of ochre.

We cannot perceive the meaning. Was this a pet, or an animal kept for its ceremonial significance? The care in the joint burial is believed to suggest some emotional link between human and fox, beyond that shown to wildlife perceived as food or clothing. It has been speculated that these pre-Natufian people coexisted with foxes that were at least half domesticated. Perhaps they scavenged rubbish on the edge of camps, along with the earliest dogs. Perhaps the behaviour so often complained about in London is more ancient than we think.

In any case, it is clear that foxes held a strong cultural significance for the later peoples of the Levant. They are commonly found in human graves in Kfar Hahoresh (modern Israel), dated to around 8,600 years ago, while stone carvings of foxes with thick brushes adorn the pillars of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, believed to be the world’s oldest temple. In Mesolithic Britain, humans who hunted deer by the shore of extinct Lake Flixton – in the North Yorkshire archaeological site of Star Carr – must have been aware of their small red neighbours. Bones from two foxes have been found at this ancient settlement, along with those of Britain’s first known domestic dogs, but there is no indication of what role, if any, canids played in their culture.

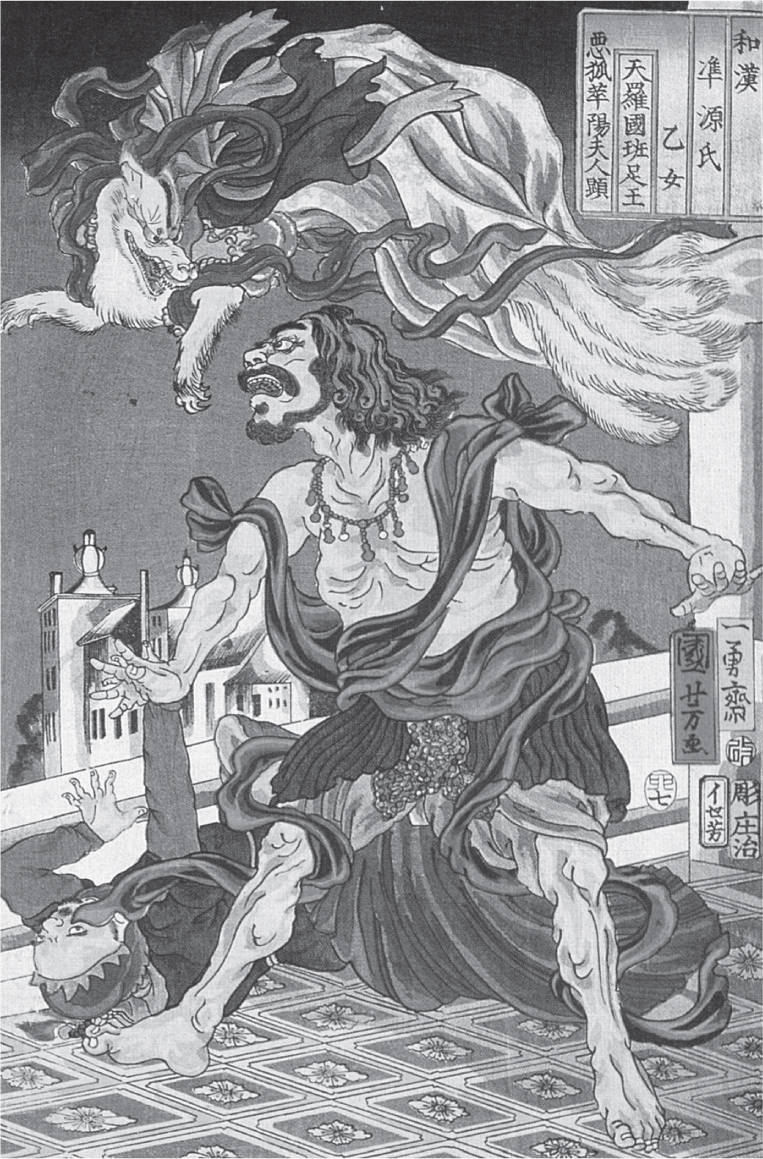

© Prince Hanzoku Terrorised by a Nine-Tailed Fox, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861) (Wikimedia Commons)

A nine-tailed kitsune in nineteenth-century Japanese art.

Later, as humanity discovered the joy of story-telling, foxes joined the cast. The oral literature of native Americans occasionally opts for a fox as a trickster, albeit a potentially handy one; according to one Apache legend, it was Fox who stole fire from the fireflies and introduced it to Earth. It is across the Pacific in Japan, however, that fox folklore reaches its most astounding heights. Kitsune – the revered fox of Japanese myth, poetry and traditional belief – has existed in human thoughts for many centuries. It even makes an appearance in what may be the world’s oldest novel: the eleventh-century epic The Tale of Genji, where a human character debates whether the figure by a tree is a woman or a shapeshifting vulpine. Kitsune delight, deceive and confuse in countless other legends; while the theme of pretending to be an attractive woman is frequent, other tales relive how they mislead travellers by lighting ghost fires at night, assume the form of cedar trees, or even become the guardian angels of samurai. Today, anime writers continue the kitsune tradition.

BACK IN EUROPE, by Roman times the uneasy relationship between foxes and agriculture had woven itself into religious rituals – in the festival of Cerealia, for example, live foxes were released into the Circus Maximus with burning torches tied to their tails. Seven hundred years later, Aesop’s tales also provide a nod to fox interactions with farmers, and – to a lesser extent – with their neighbouring wildlife. My favourite Aesop fable features a wolf taking a fox to court for theft; given the vast quantity of wolf-killed carrion that real foxes consume, it seems vaguely reasonable.

Old English literature picks up similar themes. The Fox and the Wolf, a rhyming poem from the thirteenth century, stars a fox who helps himself to some chickens and then tricks a wolf into taking the blame:

A fox went out of the wood

Hungered so that to him was woe

He ne was never in no way

Hungered before half so greatly.

He ne held neither way nor street

For to him (it) was loathsome men to meet

To him (it) were more pleasing meet one hen

Than half a hundred women.

He went quickly all the way

Until he saw a wall.

Within the wall was a house.

The fox was thither very eager (to go)

For he intended his hunger quench

Either with food or with drink

And so it continues, with the hungry fox trapping himself in a well before deceiving a wolf named Sigrim into taking his place. Ironically, this poem was written about the same time that the wolf’s howl was finally falling silent in southern Britain.

Did the fox notice the disappearance of its distant relative? Perhaps, unconsciously. As shown in Białowieża and elsewhere, the wolf was a provider as well as rival, a powerful force in the wildwood whose absence has changed these islands as much as a spoke missing from a wheel. Some species have sharply increased, and others have probably declined.

Yet civilisation has done more than simply rip out culturally troublesome natives while boosting deer and grouse for hunting. We have released millions upon millions of non-native animals into the countryside: rabbits from Spain, fallow deer from Persia, sheep from Mesopotamia, hens from south-east Asia, cats from Africa. Our trading ships accidentally added black rats from India and house mice from the Middle East, while American grey squirrels, Japanese sika deer and even Australian red-necked wallabies joined our countryside from zoos. We have persuaded ourselves that the six million sheep of Scotland are part of the ‘natural’ scene, but the Highland ecosystem evolved with none. Even the Scottish red deer population of 300,000 is far higher than in the time of the wolf. These changing grazing pressures affect the rodents and berries that foxes eat, and near-total deforestation has altered their territory sizes and feeding habits.

In a flash of geological time, we have rewritten the fox’s wildwood, in ways both graphic and subtle. We have added, taken away, replanted and concreted.

And the fox that once played its natural dodgems with the rest of the natural web will inevitably interact with the components of the new Britain that we have designed without ecological aforethought.

The fox is not an intruder into our world.

We have simply laid our modern ambitions over the landscape it already knew.

3

Where Do Foxes Live?

OPEN-TOP TOURIST BUSES and impatient black taxis battle for territory in the concrete canyons of central London; beside the gridlock, cyclists squeeze past wary pedestrians, and silent women push today’s Metro into the hands of freshly arrived train passengers. The city’s heart is within the embrace of the two highest towers of British justice: the Royal Courts with its soaring gothic spires and vaulted archways, and the Old Bailey, centuries-old theatre of the grimmest human drama. Perhaps it is no surprise that such a place tries to judge foxes too.

Humanity floods the senses. It’s noisy, so noisy, with cars, and drills, and cries of ‘Can I interest you in a …’

Salesmen offering free organic yoghurt samples, those you can escape; not the smell of vehicle exhaust, however, nor the tourists agog at military statues that screen out so much of the sky. It is musty yet grand, the mood here: intimidating, disconnecting and mesmerising. It is the bones of something; British history, perhaps, stacked so high over press crews hoping to witness more of it, while a tiny old man tries to photobomb them – his Staffordshire bull terrier is wearing a jacket emblazoned with anti-nuclear slogans.

For British people, these streets are a hook from which we dangle and debate our civilisation. For British foxes, this is a land of nothing.

Truly, nothing at all. Not a blade of grass, not a mouse, and hardly a bird in the sky. The ancient wildwood has been utterly extinguished.

At least, all logic would say so.

Yet there was a fox in this very place, not many hours past – a single scat has been deposited on a sprawling gum-spotted pavement between a bus shelter plastered with anti-police propaganda and the unsmiling security fence of the Royal Courts of Justice; a homeless man begs for coins from a populace oblivious to both wildlife and him. Over towards City Thameslink, where wet concrete was recently laid to tidy some aberration, a fox footprint is written literally into London’s frame.

That foxes thrive in leafy suburbs, wooded gardens, and even fields radically transformed by intensive agriculture is not news. But the Strand is a frontier beyond most living things. Faded carvings of red squirrels brighten one business’s wooden sign, while the tavern’s name leaves no doubt that cockfighting once brought brawls and gambling within a street-sweeper’s walk of the Inner Temple. But there is not much non-human life today, save for the pigeons where tourists break the law and feed them, and a gull or two chortling from the spires.

And a fox, somewhere.

When people exclaim that foxes are everywhere, they are both correct and imprecise. The Mammal Society’s National Mammal Atlas shows fox records in nearly every British grid square, from Cornwall to Sutherland, the Cambridgeshire fens to the Western Highlands. They are absent from the remotest islands, but mainland Britain is unquestionably the domain of the fox.

Not to an even degree, however. The weakness of a simple presence-absence map is that it gives the impression that all landscapes are equal. In reality, of course, some places have far higher fox densities than others. No one considers it surprising that humans are clustered tightly in cities, with only a smattering of houses in moorland. In one sense, the fox population also has its high-rise flats and hamlets. All land is not alike.

‘DESERT FOX!’

My guide, a khaki-clad middle-aged Indian of military bearing and Sherlockian skill in tracking all creatures wild, spins the steering wheel of our jeep. Dust spurts, the vehicle’s suspension lurches, and behind us lie treadmarks in the white, white dust. Ahead, no doubt, there is a fox; but mostly there is nothing, as only the desert knows it. Vast flat horizon and vast, vast dusty sky: a land crossed by Rabari tribals and their cattle, but immune to the modern world. I am in the Rann of Kutch in India’s Thar Desert, rattling across the dry ancient bed of the Arabian Sea. I have travelled to many remote places, but this is a landscape apart: seasonally cracked in fiery heat, swamped by monsoons, bleached by salt, and blurred by mirages – stark, wild, beautiful and brutal.

Crossing India’s Rann of Kutch, part of the Thar Desert.

The jeep has stopped.

A fox looks up at me.

It is sitting in a scrubby thicket of what the local people call toothbrush bushes, amber eyes so clear and sharp. It is a red fox, Vulpes vulpes; just like those in London, although its fur is straw-coloured, as if irradiated by the Gujarati sun. It is a curiously sobering thing to observe a fox in an overpoweringly enormous landscape – a theatre refined by torrid heat until it retains only the core essentials of grit and sky. They, too, are raw and unhumanised, and their basic needs cleanly defined.

What is actually needed for survival? We ask that question of ourselves in Robinson Crusoe and its modern spin-offs, but applying it to wildlife may remove the confusion over seeing a fox in the very heart of the metropolis. A hypothetically shipwrecked fox would probably thrive, for its needs are very simple: some shelter to evade weather and enemies, and about 120 kilocalories per kilogram of bodyweight per day. That equates to about nine voles or one rat daily – or one double cheeseburger with fries. Even the bleakest of our cities offer sustenance on this scale to a scavenger-hunter.

The cracked dust of the Gujarati desert does support some hardy plants, which in turn feed herbivores. The desert fox may seek exotic-sounding rodents such as the golden bush rat, the jird, and the Indian gerbil; insects, and the carrion left behind when wolves or jackals kill chinkara gazelle, are also possibilities. Those little thickets of toothbrush bushes – known as bets – offer shelter from the murderous May sun and stay above the waterline during the monsoon floods. Nothing more is required. However improbable it may feel to a human figure dwarfed by a blood-red sunrise, watching wild asses gallop across bone-dry salt flats, this land is perfectly suitable fox country.

On the other hand, so is the ancient forest of Białowieża in Poland, where bank voles scurry past gigantic fungi and wolves inadvertently provide a regular feast of wild boar carrion. So are the gloriously wild prairies of southern Canada, where a bewildering array of rodents whistle from meadows painted glittering silver in springtime ice storms. And so most certainly are suburban British gardens, where they may have their weekly calorie requirement handed to them on a dogfood dish every single night.

The abundance of potential food in each of these habitats is different, however. There is no ‘normal’ or ‘correct’ fox population. Each area is unique. Even the subtlest local changes can trickle upwards – in the harsh mountains of northern British Columbia, for example, areas dominated by lichens are avoided by foxes in favour of those where goat willows are found. In Belarus, forests growing upon clay soils support more prey than those on sandy deposits, and have higher fox densities. How many journalists musing over British fox numbers have thought to take samples of the local soil type?

Obviously, the more food available, the more foxes that the area can potentially support. As a general principle – and notwithstanding countertrends driven by disease and the impact of natural competitors like badgers and coyotes – foxes are distributed unevenly across their huge natural range because food itself is uneven. By that yardstick, the Strand may be even harsher than the Thar Desert; yet both have their foxes. So do the Himalayas, the sub-Arctic, the rainy Spanish mountains and Edgware tube station.

At this point, it is worth taking pause. Think of the world’s most famous animals: tigers, elephants, koalas. How many exist in a range of habitats even close to the diversity of the fox’s natural homes? Range expansion is one of the fox’s rewards for being unspecialised.

Improved odds of beating extinction are another. Replacing wildwood with cold London stone devastated many of our native species, but the fox has survived – and often thrived – during all our changes to the British landscape. A clue as to why comes from the enchanting knife-edged mountains of Sichuan in China; unlike the giant pandas that also wander this landscape, Sichuan’s foxes do not risk starvation when a single food source fails. The panda, famously, is a specialist consumer of bamboo. Should this plant flower and die, as stands do on a regular basis, the panda must move to a new area or perish. Not the fox with its catholic tastes; if, say, its stereotypical British prey of field voles runs short, it will simply switch to pouncing on wood mice or rabbits instead.

Nor are they specialised to a specific habitat. Otters can be wiped out from an entire district by river pollution. A fox population, in contrast, covers so many habitats that even if it faces an environmental disaster in farmland, it will persist in the neighbouring wood, and soon recolonise.

Wherever it lives, a fox learns an acute cartographical knowledge of its local landscape and explores it at a purposeful-seeming trot. In the Swiss Jura, foxes travel about 4 to 12 km (2.4 to 7.4 miles) daily; interestingly, their kin in a residential district in Toronto, Canada, have wider extremes, varying from 2 to 20 km (1.2 to 12.4 miles). Urban Canadian foxes are provided with far fewer deliberate handouts than their British counterparts, however, so source a large percentage of their meals directly from the land.

While foxes have allegedly been clocked at 50 kph (31 mph) in short bursts, their typical pace is far slower, and punctured by rest periods in which the fox will doze under a hedgerow or in a quiet urban corner. The Swiss foxes averaged a speed of about twelve metres per minute, although one individual, who was a transient – a fox without territory – moved considerably faster. While all this may seem like a considerable exercise regime, it is far below the 26 km (16 miles) averaged by male wolves per day. Individuals of both species that are dispersing from their parents into a new territory can wander much further.

One persistent piece of fox folklore is that they are nocturnal – that is, active by night only. Sometimes, this myth slips into the medical department via warnings that a fox enjoying the sunshine must be ill. In fact, it is no cause for alarm. Foxes do pursue a nocturnal existence in regions where they are heavily persecuted, and, as is the case for many human-caused aberrations to the natural world, we have grown accustomed to this atypical state of affairs and convinced ourselves that it is normal. Left to their own devices, foxes will adapt their activity patterns around their social and food-gathering needs. In the world’s great wildernesses, from the Thar Desert to the boggy forests of Ontario, foxes are easily found abroad during daylight hours.