полная версия

полная версияRollo in Naples

The truth was, that Mrs. Gray contrived to be tardy that morning on purpose, in order to set an example of exact and cheerful submission to the law, and to give a practical illustration, in her own case, of the strictness with which, when once enacted, such laws ought to be enforced. She knew very well that if she had once submitted to be fined, when she was only a minute and a half behind the time, and also to be refused a hearing for her excuse, nobody could afterwards expect any indulgence. The effect produced was just what she had intended, and the whole party were extremely punctual all the way. There were only a few fines assessed, and they were all paid at once, without any objection.

The road lay for a day through a small country called Tuscany. The scenery was very beautiful. Although it was so early in the spring, the wheat fields were every where very green, and in the hedges, and along the banks by the road side, multitudes of flowers were blooming. For a considerable portion of the way, where our travellers passed, the occupation of the inhabitants was that of braiding straw for bonnets; and here every body seemed to be braiding. In the streets of the villages, at the doors of the houses, and all along the roads every where, men, women, and children were to be seen standing in little groups, or walking about together in the sun, braiding the straw with a rapid motion, like that of knitting. They had a little bundle of prepared straw, at their side, and the braid which they had made hung rolled up in a coil before them. They looked contented and happy at their work, so that the scene was a very pleasing, as well as a very curious one to see.

After leaving the frontiers of Tuscany, the party entered the Papal States—a country occupying the centre of Italy, with Rome for the capital of it. The Papal States are so called because they are under the dominion of the pope. Of course the Catholic religion reigns here in absolute supremacy.

While passing through this country, the children, or rather, as Rollo would wish to have it expressed, the young people of the party, were very much interested in observing the crosses which were put up here and there by the road side, with the various emblems and symbols connected with our Saviour's death affixed to them. The first time that one of these crosses attracted their attention, Rosie was riding in the coupé with Mr. George and Rollo. There was room enough for her to sit very comfortably between them.

"See!" said Rosie; "see! Look at that cross, with all those images and figures upon it!"

The cross was pretty large, and was made of wood. It was set up by the road side, like a sign post in America. From the middle of the post out to the left hand end of the arm of the cross, there was a spear fixed. This spear, of course, represented the weapon of the Roman soldier, by which the body of Jesus was pierced in the side. From the same part of the post out to the end of the opposite arm of the cross was a pole with two sponges at the end of it, which represented the sponges with which the soldiers reached the vinegar up for Jesus to drink. Then all along the cross bar were various other emblems, such as the nails, the hammer, a pair of pincers, a little ladder, a great key, and on the top a cock, to represent the cock which crowed at the time of Peter's betrayal of his Lord.

Rollo and Rosie both looked at these things very eagerly, as the carriage drove by. Rosie seemed somewhat shocked at the sight.

"How curious that is!" said Rollo.

"I suppose it is all idolatry," said Rosie, speaking very seriously.

"No," said Mr. George, "it is not necessarily idolatry. These kind of contrivances originated in the middle ages, when the poor people who lived in all these countries were very ignorant, as indeed they are now; and inasmuch as they could not read, and there were no schools in which to teach them, they had to be instructed by such contrivances as these."

"They are very poor contrivances, I think," said Rollo.

"They would be very poor as a substitute for Sunday schools, and other such advantages as the children enjoy in America," said Mr. George; "but not very poor, after all, for the people for whom they were intended. Go back in imagination five hundred years, and conceive of a little child, born in one of these peasants' huts. His father and mother probably have never even seen a book, and are not capable of understanding any thing that is not perfectly simple and plain. The child, walking along the road side, sees this cross. He stops to look up at it, and wonders what all those little objects fastened upon it mean. After a while, when he grows a little older, he asks his mother, when she is coming by with him some day, what they mean. Now, she would not have been able, of herself, and without any aid, to give the child any regular instruction whatever, but she can explain to him about the cross, and the various emblems that are upon it."

"Yes," said Rosie; "I should think she could do that."

"The child," continued Mr. George, "in looking upon the cross, and seeing all those curious objects upon it, would ask his mother what they mean. Then his mother would tell him about the crucifixion of Christ. 'They nailed him to the cross,' she would say, 'by long nails passing through his hands and feet. Don't you see the nails?' And the child would say, 'Yes,' and look at the nails very intently. 'The soldiers climbed up by a ladder,' she would say. 'Don't you see the ladder? And by and by, when in his fever he called for some drink, they reached something up to him by a sponge fastened to the end of a long pole. Do you see the pole?' The child would look at all these things, and would get a much more clear and vivid idea of the transaction than it would be possible for so ignorant a mother to communicate to it in any other way."

"Yes," said Rosie; "I think she would."

"Thus you see," continued Mr. George, "there is a right and proper use of such contrivances as these, as well as a wrong and an idolatrous one. Unfortunately, however, pretty much all of them, though perhaps originally well intended, have degenerated, in Catholic countries, into superstition and idolatry."

The scenery of the country through which the journey lay was enchanting. The ground was every where cultivated like a garden. There were wheat fields, and vineyards, and olive orchards, and rows of mulberry trees for the silk worms, and gardens of vegetables of every kind. Here and there groups of peasants were to be seen at work, men and women together, some digging fresh fields, some ploughing, some planting, and some pruning the trees or the vines. In many places the vines were trained upon the trees, so that in riding along the road you seemed to see an immense orchard on each side of you, with a carpet of rich verdure below, and a monstrous serpent climbing up into every tree, from the grass beneath it.

The scenery was very much varied, too; and the changes were on so grand a scale that they made the views which were presented on every side appear extremely imposing. Sometimes the road lay across a wide plain, many miles in extent, but extremely fertile and luxuriant, and bounded in the distance by blue and beautiful mountains. After travelling upon one of these plains for many hours, the road would gradually approach the mountains, and then at length would enter among them, and begin to wind, by zigzags, up a broad slope, or into a dark ravine. At such places Vittorio would stop, usually at a post house at the foot of the ascent, and take an additional

horse, or pair of horses, and sometimes a yoke of oxen, to help his team draw the carriage up the hill. Many of these ascents were four or live miles long, and as the road turned upon itself in continual zigzags, there was presented to Mr. George and Rollo, and also to Mrs. Gray's party within the carriage, as they ascended, a perpetual succession of widely-extended views over the vast plain below, with the road which they had traversed stretching across it in a straight line for ten or fifteen miles, like a white ribbon.

Sometimes Mr. George and the two boys descended from the carriage, and walked for a while, in going up these hills; but generally they remained in their seats and rode. Indeed the men who came with the extra horses or oxen often rode themselves. When oxen were employed, the man used to ride, sometimes sitting on the yoke between them, and facing backward, so that he could watch them and see how they performed their work. He kept them up to their work by means of a small whip, which he had in his hand.

After reaching the top of the ascent, Vittorio would stop, and the man would detach his oxen from the team. Vittorio would pay him for his services, and then the man would come and hold out his hat to Mr. George and Rollo for a buono mano from them. Rollo always had it ready.

The party stopped every day at noon for breakfast, as Vittorio called it. The coffee, and eggs, and bread and butter, which they had early in the morning, was not called breakfast; it was called simply coffee. The breakfast, which came about noon, consisted of fried fish, beefsteaks, or mutton chops, fried potatoes, all hot, and afterwards oranges and figs. With this there was always what they called wine set upon the table, which tasted like a weak mixture of sour cider and water. Every thing, except the wine, was very good.

Mrs. Gray, however, always called this meal the dinner, and all the rest of the party were very willing to have it called so; and when they stopped at night, all that they required was tea and coffee, with bread and butter.

The inns where the party stopped were very quaint and queer. They looked, Josie said, precisely as he had imagined the inns to look which he had read about in Don Quixote. The entrance was generally under an arched passage way, where the horses and carriage could go in. From this passage a flight of broad stone steps led up into the house. The lower floor was usually occupied for stables, sheds, and other such purposes, and the one above for kitchens and the like. Higher up came the good rooms.

The apartment which was used by the party for their sitting and eating room was usually a large hall, with a brick or stone floor, and a vaulted ceiling above, painted in fresco. The walls of the room were usually painted too. There was generally a small and very coarse carpet under the table, and sometimes one before the fireplace. The doors were massive; and the locks and hinges upon them, and also the andirons and the shovel and tongs, were of the most ancient and curious construction. The first thing which the children did, on being ushered into one of these old halls, was to walk all about, and examine these various objects in detail. Rollo made drawings of a great many of them in his drawing book, to bring home and show to people in America.

The bed rooms opened out from this great hall, on the different sides of it. There were generally, but not always, two beds in each. According to the agreement, Mrs. Gray had her first choice of these rooms. She chose one, if possible, which had one wide bed in it, and one narrow one. The wide one was for herself and Rosie; the narrow one was for Susannah.

Mr. George came next in the order of choice, and he generally took a room which had only one bed in it, leaving another room with two single beds in it for the two boys. They always had a fire in the great hall every evening. Mrs. Gray usually went to her room with Rosie and Susannah at half past eight, leaving Mr. George and the two boys in the hall. The first evening of the journey—that is, the evening of the night spent at Arezzo—Mr. George told Rollo, as soon as Mrs. Gray had gone, that he had some bad news to tell him.

"What is it?" asked Rollo.

"It is that I am going to make a rule for you, that every night, from and after the time that Mrs. Gray goes into her room, you are not to have any conversation with any body."

"Why not, uncle George?" asked Rollo.

"Because I want to have the room still, so that I can write. I have journals and letters to write, and so have you,—and so I suppose has Josie; and the evening, after Mrs. Gray and Rosie have gone to their room, will be the best time to appropriate to the work. You can do your own work of this kind at that time or not, just as you please; but if you do not do it, you must not interrupt me in doing mine."

"I suppose that is a rule for me and Josie too," said Rollo.

"No," said Mr. George, "it is for you alone."

"Why is it not a rule for Josie," said Rollo, "as much as for me?"

"Because I have no authority to make any rules for Josie," replied Mr. George. "I have no authority over him at all, but only over you."

"But, uncle George," said Rollo, "if you are busy writing, and I am not allowed to talk, and Mrs. Gray and Rosie have gone to bed, Josie will not have any body to talk to."

"True," said Mr. George.

"Then I don't see but that you might just as well make the rule for him too, at once," said Rollo. "You may just as well make a rule that he shall not talk himself, as to make one that cuts him off from having any body to talk to."

"Only," replied Mr. George, "that to do the one comes within my authority, while to do the other does not."

Here Rollo was silent a few minutes, and seemed to be musing on what Mr. George had said. Presently he added,—

"Besides, uncle George, this is not put down among the rules and regulations for the journey which you drew up. We all agreed to abide by those rules, and this is not one of them."

"True," said Mr. George. "But those rules and regulations are of force as a compact only between Mrs. Gray and me, as the heads respectively of the two divisions of the party. They are not at all of the nature of a compact between Mrs. Gray and her children, nor between you and me. Her authority over her children in respect to every thing not referred to in the compact, is left entirely untouched by them, and so is mine over you."

"Well," said Rollo, drawing a long breath, "I have no objection at all to the rule. Indeed, I should like some time every evening to write and draw. I only wanted to see how you would defend your rule, in the argument."

"And how do you think the argument stands?" asked Mr. George.

"I think it stands pretty strong," said Rollo.

Rollo further inquired of his uncle whether he and Josie could not talk in their own room; but Mr. George said no. If boys were allowed to talk together after they went to bed, he said, they were very apt to get into a frolic, and disturb those who slept in the adjoining rooms.

"And besides," said Mr. George, "even if they do not get into a frolic, they sometimes go on talking to a later hour than they imagine, and the sound of their voices is heard like a constant murmuring through the partitions, and disturbs every body that is near. So you must do all your talking in the course of the day, and when eight o'clock comes, you must bring your discourse to a close. You may sit up as long as you please to read or write; but when you get tired of those employments, you must go to bed and go to sleep."

The rule thus made was faithfully observed during the whole journey.

It was Monday morning when the party left Florence, and on Saturday afternoon at three o'clock, the carriage drew up at the passport office just under the great gate called the Porta del Popolo, at Rome. The party spent the Sabbath at Rome, and on the Monday morning after they set out again. On the following Thursday they arrived at Naples, and there they all established themselves in very pleasant quarters at the Hotel de Rome—a hotel which, being built out over the water from the busiest part of the town, commands on every side charming views, both of the town and of the sea.

Chapter IV.

Situation of Naples

Naples is situated on a bay which has the reputation of being the most magnificent sheet of water in the world. It is bordered on every side by romantic cliffs and headlands, or by green and beautiful slopes of land, which are adorned with vineyards and groves of orange and lemon trees, and dotted with white villas; while all along the shore, close to the margin of the water, there extends an almost uninterrupted line of cities and towns round almost the whole circumference of the bay. The greatest of these cities is Naples.

SITUATION OF NAPLES.

But the crowning glory of the scene is the great volcano Vesuvius, which rises a vast green cone from the midst of the plain, and emits from its summit a constant stream of smoke. In times of eruption this smoke becomes very dense and voluminous, and alternates from time to time with bursts of what seems to be flame, and with explosive ejections of red-hot stones or molten lava. Besides the cities and towns

that are now to be seen along the shore at the foot of the slopes of the mountain, there are many others buried deep beneath the ground, having been overwhelmed by currents of lava from the volcano, or by showers of ashes and stones, in eruptions which took place ages ago.

Of course there is every probability that there will be more eruptions in time to come, and that many of the present towns will also be overwhelmed and destroyed, as their predecessors have been. But these eruptions occur usually at such distant intervals from each other, that the people think it is not probable that the town in which they live will be destroyed in their day; and so they are quiet. Of course, however, whenever they hear a rumbling in the mountain behind them, or notice any other sign of an approaching convulsion, they naturally feel somewhat nervous until the danger passes by.

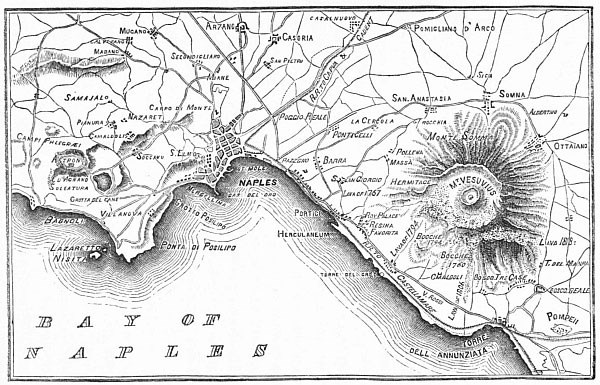

Naples is built on the northern shore of the bay You will see by the map on the preceding page just what the situation of the town is, and where Vesuvius is in relation to it. Vesuvius, you observe, stands back a little from the sea, but the slope of land extends quite down to the margin of the water. You perceive, however, that there is a carriage road, and also a railroad, passing along the coast between the mountain and the sea.

Besides the villages and towns laid down on the map, upon this coast, there are many little hamlets scattered along the way, so that, as seen across the water from Naples, there seems to be, as it were, a continued town, extending along the whole line of the shore.

Among the places named on the map you see the sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii marked. Pompeii lies to the south-east from the mountain, and Herculaneum to the south-west. Of course the lava, in breaking out from the crater in different eruptions, runs down the mountain, sometimes on one side and sometimes on another. It is the same with the showers of stones and ashes, which are carried in different directions, according to the course of the wind.

Very near the site of Herculaneum you see a small town laid down, named Resina. This is the place where people stop when about to make the ascent of Vesuvius, and leave the carriage in which they came from Naples. If they come by the railroad, they leave the train at the Portici station, which, also, you will see upon the map, and thence go to Resina by a carriage.

At Resina they take another carriage, or sometimes go on in the same, until they get up to what is called the Hermitage, the place of which you also see marked on the map. The Hermitage is so called because the spot was once the residence of a monk who lived there alone in his cell. It is now, however, a sort of ruin.

There is no carriage road at all beyond the Hermitage, and here, accordingly, the party of travellers take mules or donkeys, to go on some distance farther. At last they reach a part of the mountain which is so steep that even mules and donkeys cannot go; and here the people are accordingly obliged to dismount, and to climb up the last part of the ascent on foot, or else to be carried up in a chair, which is the mode usually adopted for ladies. You will see how Mr. George and Rollo managed, in the next chapter.

The ruins of Herculaneum can be visited on the same day in which you make the ascent of Vesuvius; for, as you see by the map, they are very near the place, Resina, where the ascent of the mountain commences. Pompeii, however, is much farther on, and usually requires a separate day.

Besides, it takes much longer to visit Pompeii than Herculaneum, on account of there being go much more to see there. The reason for this is, that the excavations have been carried on much farther at Pompeii than at Herculaneum. Herculaneum was buried up in lava, and the lava, when it cooled, became as hard as a stone; whereas Pompeii was only covered with ashes and cinders, which are very easily dug away.

Besides, Herculaneum was buried very deep, so that, in order to get to it, you have to go far down under ground. The fact that there was an ancient city buried there was discovered about a hundred and fifty years ago, by a man digging a well in the ground above. In digging this well, the workmen came upon some statues and other remains of ancient art. They dug these things out, and afterwards the excavations were continued for many years; but the difficulties in the way were so great, on account of the depth below the surface of the ground where the work was to be done, and also on account of the hardness of the lava, that after a while it was abandoned. People, however, now go down sometimes through a shaft made near the well by which the first discovery was made, and ramble about, by the light of torches, which they carry with them, among the rubbish in the subterranean chambers.

The site of Pompeii was discovered in the same way with Herculaneum, namely, by the digging of a well. Pompeii, however, as has already been said, was not buried nearly as deep as Herculaneum, and the substances which covered it were found to be much softer, and more easily removed. Consequently a great deal more has been done at Pompeii than at Herculaneum in making excavations. Nearly a third of the whole city has now been explored, and the work is still going on.

The chief inducement for continuing to dig out these old ruins, is to recover the various pictures, sculptures, utensils, and other curious objects that are found in the houses. These things, as fast as they are found, are brought to Naples, and deposited in an immense museum, which has been built there to receive them.

You will see in a future chapter how Rollo went to see this museum.

Vesuvius, Herculaneum, and Pompeii are all to the eastward of Naples, following the shore of the bay. To the westward, at the distance of about a mile or two from the centre of the town, is a famous passage through a hill, like the tunnel of a railway, which is considered a great curiosity. This passage is called the Grotto of Posilipo. You will see its place marked upon the map. The wonder of this subterranean passage way is its great antiquity. It has existed at least eighteen hundred years, and how much longer nobody knows. It is wide enough for a good broad road. When it was first cut through, it was only high enough for a carriage to pass; but the floor of it has been cut down at different times, until now the tunnel is nearly seventy feet high at the ends, and about twenty-five in the middle. High up on the sides of it, at different distances, you can see the marks made by the hubs of the wheels, as they rubbed against the rocks, at the different levels of the road way, in ancient times.

On passing through the grotto in a carriage, or on foot, the traveller comes out to an open country beyond, where he sees a magnificent prospect spread out before him. The road goes on along the coast, and comes to several very curious places, which will be described particularly in future chapters of this volume.

On the afternoon of the day when Mr. George and his party arrived at the hotel, just before sundown, Rollo came into Mrs. Gray's parlor, where Mr. George and all the rest of the party, except Josie, were sitting, and asked them to go with him and see a place which he and Josie had found.

"Where is it, and what is it?" asked Mrs. Gray.

"You must come and see," said Rollo. "I would rather not tell you till you come and see."

But Mrs. Gray, being somewhat fatigued with her ride, and being, moreover, very comfortably seated on a sofa, seemed not inclined to move.

![Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]](/covers_200/36364270.jpg)