полная версия

полная версияWho Are Happiest? and Other Stories

CRUEL SPORT.

The two dogs were brought forward by the two lads, whose parents knew nothing of the affair, and by pushing them against, and throwing them upon each other, irritated and angered them until they finally went to work in real earnest, greatly to the delight of the lookers-on. Rover fought bravely, but he was evidently no match for his larger and stronger antagonist, who tore him savagely, while he seemed unable to penetrate Nero's thick yielding skin. The shouts that arose from the group around were all in favour of Nero, who was a general favourite—as he was one of those large, peaceable, benevolent fellows, belieing his name, whom all liked, while there was something of the churl and savage about Rover, that caused him to have but few friends.

The contest had waged about ten minutes, fiercely, and Rover was evidently getting "worsted," when Dick, who had been constantly encouraging his dog, stooped close to his ear, and spoke something in a low, quick, energetic tone.

Instantly Rover crouched down, and darting forward, seized the forepaw of Nero in his mouth, and commenced gnawing it eagerly. The noble animal, thus unexpectedly and basely assailed, found the pain to which he was suddenly subjected so great as to take away all power of resistance. He would not utter a cry, but sat down, and permitted the other dog to gnaw away at his tender foot without a single sign of suffering. As the cry of pain, the dog's "enough," was to terminate the battle, the fine fellow was permitted thus to suffer for several minutes, before the bystanders came forward and pulled Dick Lawson's dog off. Nero would have died before a sound could have been extorted from him.

As Nero had not cried "enough," Bob Markland contended afterwards that his dog had not been whipped, to settle which difference of opinion he and Dick had several hard battles, in which the latter, like his dog, always came off the victor. The upshot of all these contests was, the expulsion of Dick from the Sabbath-school, into which he carried the bickerings engendered through the week. Another reason for his expulsion was the frequency with which he played truant, and of his having, in several instances, enticed other boys away from the school for the same purpose.

Except Mr. Acres, nearly every man, woman and child in the neighbourhood sincerely disliked, and some actually hated Dick Lawson, for there was hardly a family some member of which had not been annoyed by him in one form or another. But Mr. Acres liked the spirit of the lad, as well as his thorough independence in regard to the opinion of others.

This man, who had first thrown temptation into the lad's way, and encouraged him to persevere in a conduct which nearly all condemned, was not a wilfully bad man. By most people he was called a good-hearted, benevolent person. The truth was, he was not a wise man. When young, he had indulged in such amusements as catching young birds, fighting dogs and cocks, and attending horse-races, and all the exciting scenes to which he could get access. But none of these things corrupted him so far as to make him a decidedly bad man in the community. As he grew up, he gradually laid aside his boyish follies; saved up his money; bought himself a small farm, and, in time, became quite a substantial man, so far as worldly goods were concerned.

Contrasted with himself were several lads whose parents had been exceedingly strict with them, and who had, as they grew up, shaken off the trammels of childhood and youth, run into wild extravagances of conduct, and some into wicked and vicious habits, from which they were never reclaimed. Comparing his own case with theirs, his short-sighted conclusion was that boys ought to be allowed as much freedom as possible, and this was why he encouraged Dick, who was an exceedingly bright lad, in the course he had been so willing to pursue. He knew nothing at all of the different hereditary tendencies to evil that exist in the mind. His observation had never led him to see how two persons, raised in precisely the same manner, would turn out very differently—the one proving a good, and the other a bad citizen. His knowledge of human nature, therefore, never for a moment caused him to suspect, that in encouraging a feeling of cruelty in Dick Lawson, he might be only putting blood upon the tongue of a young lion—that there might be in his mind hereditary tendencies to evil, which encouragement to rob a bird's nest, or to set two dogs to fighting, by one occupying his position and influence, might cause to become so active as to ultimately make him a curse to society.

And such, in a year or two, Dick seemed becoming. He had in that time, although but fourteen years of age, got almost beyond his mother's control. His dog and himself were the terror of nearly all the dogs and boys in the neighbourhood, for both were surly, quarrelsome, and tyrannical. Even Mr. Acres had found it necessary to forbid him to appear on his premises. Rover having temporarily lamed, time after time, every one of his dogs, and Dick having twice beaten two of his black boys, farm-hands, because of some slight offence. To be revenged on him for this, he robbed a fine apricot-tree of all its fruit, both green and ripe, on the very night before Mr. Acres had promised to send a basket full, the first produced in the neighbourhood that spring, to a friend who was very much esteemed by him.

Though he strongly suspected Dick, yet he had no proof of the fact, and so made no attempt to have him punished.

Shortly after, the boy was apprenticed to a tanner and currier, a severe man, chosen as his master in the hope that his rigid discipline might do something towards reclaiming him. As the tanner had as many dogs as he wanted, he objected to the reception into his yard of Dick's ill-natured cur. But Dick told his mother that, unless Rover were allowed to go with him, he would not go to the trade selected for him. He was resolute in this, and at last Mrs. Lawson persuaded Mr. Skivers, the tanner, to take him, dog and all.

In his new place he did not get along, except for a very short time, without trouble. At the end of the third month, for neglect of work, bad language, and insolence, but particularly for cruelties practised upon a dog that had gotten the mastery over Rover, Mr. Skivers gave him a most tremendous beating. Dick resisted, and fought with might and main, but he was but a boy, and in the hands of a strong and determined man. For a time this cowed Dick, but in the same ratio that his courage fell when he thought of resisting his master single-handed, rose his bitter hate against him. Skivers was a man who, if he had reason to dislike any one about him, could not let his feelings remain quiescent. He must be doing something all the while to let the victim of his displeasure feel that he was no favourite. Towards Dick, he therefore maintained the most offensive demeanour, and was constantly saying or doing something to chafe the boy's feelings. This was borne as patiently as possible, for he did not again wish to enter into a contention in which he must inevitably get severely beaten. Skivers was not long in perceiving that the way to punish Dick the most severely was to abuse his dog; and he, therefore, commenced a systematic process of worrying Rover. This Dick could illy bear. Every time his master would drive Rover from the yard, or throw sticks or stones at him, the boy would make a new and more bitter vow of retaliation in some form.

One day, Rover and a large dog belonging to Skivers got into a fight about something. Dick's interest in his dog brought him at once to the scene of action. His master, seeing this, ordered him, in a harsh, angry tone, to clear out and mind his own business. As he did so, he took a large club, and commenced beating Rover in a most cruel manner. Dick could not stand this. His blood was up to fever heat in an instant. Seizing a long, heavy pole, used for turning and adjusting hides in the vats, he sprang towards Skivers, and giving it a rapid sweep, brought it with tremendous force against his head, knocking him into a vat half-full of a strong infusion of astringent bark, to the bottom of which he instantly sank.

So incensed did the lad feel, that he made not the slightest attempt to extricate his master from a situation in which death must have inevitably ensued in a few minutes, but walked away to another part of the yard. Two or three journeymen, however, who witnessed the whole affair, were on the spot in a moment, and took out the body of Skivers. He was completely insensible. There was the bloody mark of a large wound on his head. A physician was immediately called, who bled him profusely. This brought him back to consciousness. In a day or two he was out again, and apparently as well as ever. In the mean time, both Dick and his inseparable companion, Rover, had disappeared, and gone no one knew whither. No effort was made to discover the place to which the boy had fled, as every one was too much rejoiced that he had left the village, to care about getting him back. About twelve months after, his mother died—her gray hairs brought down to the grave in sorrow. Year after year then passed away, and the memory of the lad was gradually effaced from the minds of all, or retained only among the dim recollections of the past.

Mr. Acres, who had first placed temptation in the way of Dick Lawson, continued to prosper in all external things, and to hold his position of influence and respectability in the neighbourhood. He, perhaps, more than others, thought about the lad in whom he had once felt a good deal of pride and interest, as exhibiting a fair promise for the future. But he never felt exactly easy in mind when he did think of him. Something whispered that, perhaps, he had been to blame in encouraging his wild habits. But, then, how could he have dreamed, he would argue, that the boy had in him so strong a tendency to evil as the result had proved. He had once been just as fond as Dick had shown himself to be of bird's-nesting, dog-fighting, &c., but then, as soon as he had sown a few wild oats, he sobered down into a steady and thrifty farmer of regular habits. And he of course expected to see Dick Lawson do the same.

"And who knows but that he has?" he would sometimes say, in an effort at self-consolation.

It was some five or six years from the time Dick left the village, that Mr. Acres was awakened one night from sleep by a dream that some one had opened the door of the chamber where he slept. So distinct was the impression on his mind that some one had entered, that he lay perfectly still, with his eyes peering into the darkness around, in order to detect the presence of any one, should the impression on his mind really be true. He had lain thus, with every sense acutely active, for only a moment or two, when a sound, as of a stealthy footstep, came distinctly upon his ear, and at the same moment, a dark body seemed to move before his eyes, as if crossing the room towards that part of it where stood a large secretary, in which was usually contained considerable sums of money.

Mr. Acres was a brave man, but thus suddenly awakened from sleep to find himself placed in such an emergency, made him tremble. He continued to lie very still, straining his eyes upon the dark moving object intently, until the figure of a man became perfectly distinct. The robber, for such the intruder evidently was, had now reached the secretary, where he stood for a few moments, quietly endeavouring to open it. Finding it locked, he moved off, and passed around the room, feeling every chair and table that came in his way. This Mr. Acres could now distinctly perceive, as his eyes had become used to the feeble light reflected from the starry sky without. At last his hands came in contact with a chair upon which the farmer had laid his clothes on disrobing himself for bed. These seemed to be the objects of his search, for he paused with a quick eager movement, and commenced searching the ample pockets of a large waistcoat. The slight jingle of the farmer's bunch of keys soon explained the movement. Before the robber had fairly gotten back to the secretary, Mr. Acres's courage had returned, and with it no small share of indignation. He rose up silently, but, unfortunately, as his foot touched the floor, it came in contact with a chair, which was thrown over with a loud noise. Before he could reach a large cane, for which he was making, a heavy blow from the robber laid him senseless.

When again conscious, Mr. Acres found himself still in total darkness. On attempting to move, there was an instant, almost intolerable pain in his head, as if from a violent blow. On lifting his hand and placing it upon the spot where the pain seemed most severe, it came in contact with a cold, slimy mass of what he at once knew to be blood. His first effort to rise was accompanied by a feeling of faintness, that caused him to stretch himself again upon the floor, where he lay for some time endeavouring to collect his scattered senses. After he had fully comprehended the meaning of his alarming situation, he made another and more successful effort to rise. Sitting up in the middle of the room, and straining his eyes into the darkness, he began to see more and more distinctly each moment. He was soon satisfied that he was alone. It did not take long after this to arouse the whole house. An examination resulted in ascertaining the fact that his secretary had been robbed of five hundred dollars in gold.

By daylight, the whole neighbourhood was aroused, and some twenty or thirty men were in hot pursuit of the robber, who was arrested about twenty miles away from the village and brought back. The money taken from the secretary of Mr. Acres, was found upon his person, and fully identified. The man proved to be quite young, seeming to have passed but recently beyond the limit of minority. But even young as he was, there was a look of cruel and hardened villany about him, and an expression of settled defiance of all consequences. He gave his name as Frederick Hildich. A brief examination resulted in his committal to await the result of a trial for burglary at the next court.

The day of trial at length came. The action of the court was brief, as no defence was set up, and the proof of the crime clear and to the point. During the progress of the trial, the prisoner seemed to take little interest in what was going on around him, but sat in the bar, with his head down, seemingly lost in deep abstraction of mind. At the conclusion of the proceedings, when the court asked what he had to say why the sentence of the law should not be pronounced upon him, the prisoner slowly arose to his feet, lifted his head, glanced calmly around for a few moments, until his eyes rested upon Mr. Acres, whom he regarded for some time with a fixed, penetrating, and meaning look. Then, turning to the Bench, he said in a firm, distinct voice:

"Your Honour—Although I have nothing to urge against the execution of the laws by which I am condemned, I would yet crave the privilege of making a few remarks, which may, perhaps, be useful. The principal witness against me is Mr. Acres,—and upon his testimony, mainly, so far as positive proof goes, I am convicted of a crime, the commission of which I have no particular reason for wishing to deny. But, if I have wronged him, how far more deeply has he wronged me. If I have robbed him of a few paltry dollars, he has robbed me of that which he can never restore, either here or hereafter. In a word, your honour, I stand here, in the presence of this court, and the people of this town, and charge upon that man (pointing to Acres) the cause of my present condition. My real name is Richard Lawson!"

As he said this, the prisoner's voice failed him, and he paused for a few moments, overcome with emotion. A universal exclamation of surprise passed through the court-room, and there was scarcely an individual present who did not wonder why he had not discovered this fact for himself long before. For, sure enough, it was Dick Lawson, and no one else, who stood there humbled under the iron hand of the law. As for Mr. Acres, he became instantly pale and agitated—and when the prisoner again looked up and fixed his eyes upon him, his own fell to the floor, as if he were conscience-stricken.

"To that man," resumed the individual, at the bar, pointing steadily toward the farmer, "as I just said, am I indebted for my ruin. A wild, but innocent boy, he first led me into conscious wrong, by tempting me with money to rob a bird's nest. The young mocking-bird was procured for him, but at the expense of a violated conscience; for a voice within me spoke loudly against the act of cruelty about to be practised upon the mother-bird and her young. But I stifled that inward monitor, and stilled the voice that urged me to depart not from the path of innocence. I saw that the act was a cruel one, and felt that it was a cruel one—but to be asked to do even a wrong act by a man to whom I looked up, as I then did to Mr. Acres, was to rob the wrong act of more than half of its apparent evil—and so I performed the cruel deed, small as it was, deliberately. From the moment I took the young bird in my hand, all my scruples were gone, and after that it was one of my greatest pleasures to rob birds' nests, and to kill the older birds with stones. My dog Rover, who is no doubt as well remembered as myself, was given me by Mr. Acres, and I was, moreover, encouraged by that individual to make Rover fight, and to fight myself, whenever it came in the way. Had he discouraged this in me; had he told me that fighting was wrong, his precept for good would have been as powerful as his precept for evil. He was kind to me, and had gained my entire confidence, and could have made almost any thing of me. My cruel, tyrannizing temper, thus encouraged, grew rapidly, until at last I took no delight in any good. Finally expelled from the Sabbath-school, and persecuted for my ill-behaviour and annoyance of almost every one, I became reckless, and finally left this neighbourhood. Five or six years of evil brought me at last into a strait. I could not gain even a common livelihood. I must starve or beg. In this state I thought of my corrupter—of the man who had been the cause of my wretchedness, and I resolved that he should, at least, pay some small penalty for what he had done. In a word, I resolved to rob him—and did so. And now I stand here to await the sentence of the law for this crime."

The prisoner then suffered his head to fall upon his bosom, and sank slowly into the seat from which he had arisen. A profound and oppressive silence reigned through the court-room, broken at last by the judge, who said—

"Richard Lawson, alias Frederick Hildich, stand up, and receive the sentence of the law."

The prisoner arose, and looked the judge steadily in the face, while a sentence of imprisonment in the penitentiary for three years was pronounced upon him in a voice of assumed sternness.

When the unfortunate man was removed by an officer, the crowd slowly withdrew, conversing in low, subdued voices, and Mr. Acres turned his step homeward, the unhappiest man of all who had stood that day in the presence of offended justice.

And here we must leave the parties most concerned in the events of our brief story—Richard Lawson to fill up the term of his imprisonment in the penitentiary; and Mr. Acres to muse, in painful abstraction, over the ruin his thoughtlessness had wrought—the ruin of an immortal soul—the corruption of a fellow creature, born to become an angel of heaven, but changed by his agency into a fit subject for the abodes of evil spirits in hell.

THE MEANS OF ENJOYMENT

One of the most successful merchants of his day was Mr. Alexander. In trade he had amassed a large fortune, and now, in the sixtieth year of his age, he concluded that it was time to cease getting and begin the work of enjoying. Wealth had always been regarded by him as a means of happiness; but, so fully had his mind been occupied in business, that, until the present time, he had never felt himself at leisure to make a right use of the means in his hands.

So Mr. Alexander retired from business in favour of his son and son-in-law. And now was to come the reward of his long years of labour. Now were to come repose, enjoyment, and the calm delights of which he had so often dreamed. But it so happened, that the current of thought and affection which had flowed on so long and steadily, was little disposed to widen into a placid lake. The retired merchant must yet have some occupation. His had been a life of purposes, and plans for their accomplishment: and he could not change the nature of this life. His heart was still the seat of desire, and his thought obeyed, instinctively, the heart's affection.

So Mr. Alexander used a portion of his wealth in various ways, in order to satisfy the ever-active desire of his heart for something beyond what he had in possession. But, it so happened, that the moment an end was gained—the moment the bright ideal became a fixed and present fact, its power to delight the mind was gone.

Mr. Alexander had some taste for the arts. Many fine pictures already hung upon his walls. Knowing this, a certain picture-broker threw himself in his way, and, by adroit management and skilful flattery, succeeded in turning the pent-up and struggling current of the old gentleman's feelings and thoughts in this direction. The picture-dealer soon found that he had opened a new and profitable mine. Mr. Alexander had only to see a fine work of art to desire its possession; and to desire was to have. It was not long before his house was a gallery of pictures.

Was he any happier? Did these pictures afford him a pure and perennial source of enjoyment? No; for, in reality, Mr. Alexander's taste for the arts was not a passion of his mind. He did not love the beautiful for its own sake. The delight he experienced when he looked upon a fine painting was mainly the desire of possession; and satiety soon followed possession.

One morning Mr. Alexander repaired alone to his library, where, on the day before, had been placed a new painting, recently imported by his friend the picture-dealer. It was exquisite as a work of art, and the biddings for it had been high. But he succeeded in securing it for the sum of two thousand dollars. Before he was certain of getting this picture, Mr. Alexander would linger before it, and study out its beauties with a delighted appreciation. Nothing in his collection was deemed comparable therewith. Strangely enough, after it was hung upon the walls of his library, he did not stand before it for as long a space as five minutes; and then his thoughts were not upon its beauties. During the evening that followed, the mind of Mr. Alexander was less in repose than usual. After having completed his purchase of the picture, he had overheard two persons, who were considered good judges of art, speaking of its defects, which were minutely indicated. They likewise gave it as their opinion that the painting was not worth a thousand dollars. This was throwing cold water on his enthusiasm. It seemed as if a veil had suddenly been drawn from before his eyes. Now, with a clearer vision, he could see faults, where before every defect was thrown into shadow by an all-obscuring beauty.

On the next morning, as we have said, Mr. Alexander entered his library, to take another look at his purchase. He did not feel very happy. Many thousands of dollars had he spent in order to secure the means of self-gratification; but the end was not yet gained.

A glance at the new picture sufficed, and then Mr. Alexander turned from it with an involuntary sigh. Was it to look at other pictures? No. He crossed his hands behind him, bent his eyes upon the floor, and, for the period of half an hour, walked slowly backwards and forwards in his library. There was a pressure on his feelings—he knew not why; a sense of disappointment and dissatisfaction.

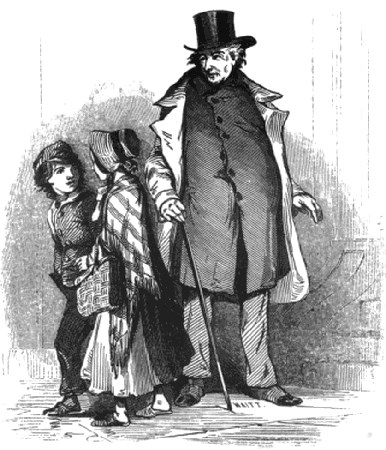

No purpose was in the mind of Mr. Alexander when he turned from his library, and, drawing on his overcoat, passed forth to the street. It was a bleak winter morning, and the muffled passengers hurried shivering on their way.

"OH! I WISH I HAD A DOLLAR."

"Oh! I wish I had a dollar."

These words, in the voice of a child, and spoken with impressive earnestness, fell suddenly upon the ears of Mr. Alexander, as he moved along the pavement. Something in the tone reached the old man's feelings, and he partly turned himself to look at the speaker. She was a little girl, not over eleven years of age, and in company with a lad some year or two older. Both were coarsely clad.