полная версия

полная версияThe Journal of Negro History, Volume 7, 1922

Speaking of John Randolph the Master, old Mr. Fountain Randolph said "my father said he had lots of peculiarities about him. He never sold a slave & never allowed them to be abused. He never sold any produce as corn, meat and stuffs used by the slaves without first enquiring of the slaves if they could spare it. He would say to the person wanting to buy "You must ask my slaves." "and my mother said:" continued Mr. Randolph "He would often go among his slaves, parents & children & pat them on the head saying 'all these are my children.' His chief body guard was a faithful slave called John White for whom some special mention & provision was made in the will."

This man went with the colony to Ohio, was respected by the others & treated by them just as if he had not been favored by the Master, says Mr. Randolph.

The master gave as his reason for not marrying that should he die—his heirs would want to hold the slaves or sell them and he wanted neither of the things to happen.

He often called the slaves together and asked which they preferred: "Freedom while he lived or after his death and they always said after his death."

Mr. Fountain Randolph has in his possession an old copy of "Life of Randolph of Roanoke" written by Hugh A. Garland, & Published in New York in 1850 by D. Appleton & Co. and Published in Phila. the same year by G. S. Appleton & Co. It is in two volumes. Mr. Randolph had both Vols. but loaned Volume I to the Indianapolis lawyer & has not been able to get it back.

The Randolph will is set forth in Vol. II from which I made the following notes:

Will 1st written in 1819 & left with Dr. Brockenbrough saying:

"I give my slaves their freedom to which my conscience tells me they are justly entitled. It has long been a matter of deepest regret to me that the circumstances under which I inherited them and the obstacles thrown in the way by the laws of the land have prevented my emancipating them in my life time which it is my full intention to do in case I can accomplish it. All the rest & residue of my estate (with exceptions herein after made) whether real or personal, I bequeath to Wm. Leigh, Esq., of Halifax, Atty at Law, to the Rev. Wm. Meade of Frederic and Francis Scott Key Esq., of Georgetown, D. C. in trust for the following uses and purposes viz:

1st To provide one or more tracts of land in any of the States or Territories not exceeding in the whole 4000 acres nor less than 2000 acres, to be partitioned & apportioned by them in such manner as to them shall seem best, among the said slaves.

2nd To pay the expense of their removal & of furnishing them with necessary cabins, clothes & utensils."

In 1821 another Will was written saying: 1st I give and bequeath to all my slaves their freedom—heartily regretting that I have ever been the owner of one.

2nd I give to my executor a sum not exceeding $8,000 or so much thereof as may be necessary to transport & settle said slaves to & in some other state or Territory of the United States, giving to all above the age of 40 not less than ten acres of land each.

Then special annuities to his "old faithful servants Essex & his wife, Hetty, same to woman servant Nancy to John (alias Jupiter) to Queen and to Johnny his body servant." In 1826 a codicil was written confirming previous wills. In 1828 a codicil to will in possession of Wm. Leigh Esq., confirming it as his last will and testament revoking any and all other wills or codicil at variance that may be found.

In 1831 on starting home from London another codicil adding to former provisions as follows:

Upwards of 2000 £ were left in the hands of Baring Bros, & Co of London & upwards of 1000 £ in the hands of Gowan & Marx to be used by Leigh as fund for executing the will regarding the slaves.

Respectfully yours,The following account and the clipping attached thereto give an interesting story of the success and the philanthropy of a Negro:

I was born in Milledgeville, Ga. about the year 1867. My mother belonged to a white man by the name of Dr. Garner Edwards. My father belonged to a different family. About two weeks after I was born my mother died. She was still working for the same people who once owned her. She was much liked by them so they decided to keep her child and try and raise it. They taught me at home so when I went to school I knew how to read and write. They sent me to a school four or five years. Dr. Edwards had a son by the name of Miller or (Buck) Edwards. It was through him that I received my schooling as Dr. was old and Miller was the support of the house. After years Miller died and I had to stop school and go to work. I worked in a number of stores in Milledgeville and was always trusted.

My earnings I always carried them home and gave them to the white people. They never asked me for anything. They gave me all I made but I thought they needed it more than I, so that went on for a number of years. At this time I was about twenty years old so I told them I was going to Macon, Ga. to work. I secured work at the Central R. R. Shop. I worked on the yard a number of months. During that time I was called off the yard at different times to work in the office when some one wanted to get off. Finally I was given one office to clean up. My work was so satisfactory until I was moved from the shop to the car shed and was given a job of delivering R. R. Mail. I was promoted three times in two years. It was then where I became acquainted with a route agent. He boarded at the same house. We were often in conversation. He was telling me of a daughter he had in school. I told him I wanted to go but I was not able. He ask me did I know Booker Washington. I said no. He said well he runs a school where you can work your way through school. I told him I would like to go so he gave me the address. I wrote and received a little pamphlet. I was looking for a catalogue so I was much disappointed in getting this little book and said it was not much. But I decided to go and try. I did not have much money. I had been living high in Macon and spending all I made. I did not stay to make more but left in about four weeks after I received the first letter. I asked for a pass to Montgomery. It was given me. I arrived in Montgomery with 10 or 12 dollars. I said well I am going to school so I will have a good time before going so I got broke did not know any one, thought my trip was up. I walked up the street one morning. In passing a drug store I saw a young man inside. I step back a few steps to look again. I recognized it to be some one I knew some years ago so the first thing came in mind was to borrow enough money from him to take me to Tuskegee. After a long talk he asked me where I was going and what I was doing there, so now was my chance. I told him I was on my way to Tuskegee. He said it was a fine that he had worked up there. I told him I had spent all the money I had and wanted to borrow enough to get there which he very liberally responded. But before I saw him I begged a stamp and some paper and wrote to Mr. Washington that if he would send me the money to come from there I would pay him in work when I came. I received an answer from Mr. Logan stating that if I would go to work there it would not be long before I would get enough money to come on so I borrowed some money from that man and landed there with $3.40. The food was very poor so I soon ate that up. I was not satisfied at first and wanted to leave but I did not have any money and did not want to write home because I did not want my white people to know where I was until I accomplished something so I made up my mind that if all these boys and girls I see can stay here, I can too. So I was never bothered any more. I went to work at the brick mason's trade under Mr. Carter. They did not have any teacher at that time. Soon after Mr. J. M. Green came and I learned fast and was soon a corner man. I was a student two years and nine months. After that time I secured an excuse and left for home. I was very proud of my trade and all seemed to be surprised as no one knew where I was but my white people. I wrote to them once a month and they always answered and would send me money, clothes something to eat. They were very glad I had gone there and tried to help me in many ways when I got home. They had spoken to a contractor and I had no trouble in getting work. I worked at home about two years. Meantime I received a letter from Mr. Washington stating he would like for me to return and work on the chapel, which I did. At this time I was a hired man and not a student. I worked for the school five or six years. Within that time I had helped build two houses in Milledgeville Ga. and paid for them and bought me thirty acres of land in Tuskegee, Ala. I feel very grateful to the school for she has help me in a great many ways. I have always had a great desire to farm but I said I never would farm until I owned my land and stock.

So three years ago I bought some land and I am at the present time farming. I like it and I expect I will continue at farming instead of my trade. My white people are as good to me now as they were when I was a boy. I made it a rule not to ask them for anything unless I was compelled to but when I do they always send more that I ask for. I will say that I did not know the real value of a dollar until I had spent 2 years and 9 months at Tuskegee. The teachings from the various teachers and the Sunday evening talks of Mr. Washington made an indellible impression upon my heart. I remember the first Sunday evening talk that I ever heard him. He spoke of things that were in line with my thoughts and I have tried to put them in practice ever since I have been connected with the school. There is one word I heard Mr. W. Speak 13 years ago that has followed me because I was taught the same words by my white people and they were not to do anything that will bring disgrace upon the school you attend. I was taught not to do anything that will bring disgrace upon the people that raised you. There are a number of other thoughts that I will not take time to mention for I have thanked him a thousand times for those Sunday evenings talks.

Garner J. EdwardsThe Republican—Springfield, Mass.—Dec. 6, 1902.

The Milledgeville (Ga.) News of November tells the following interesting story of one of the young colored men connected with Booker T. Washington's school at Tuskegee, in regard to the work of which Mr. Washington is to speak in the high school hall in this city the 10th:—

A case has come to the News which deserves more than a mere passing mention. The story deals with the prettiest case of loyal Negro's devotion and gratitude to his white benefactors that we ever knew of. When we refer to the incident as a story we mean that there is in it a good subject for a real story with a genuine hero. And every word of it is true; in fact, there is more truth in it than we feel at liberty to tell.

About 30 years ago Buck Edwards of this city picked up a very small and dark-colored boy and undertook, in his language, "to raise him and make something of him." Mr. Edwards clothed and fed the boy, and in a general way taught him many things. In return the boy was bright and quick, and rendered such return as a boy of his years could. His name was Garner, and in time he came to be known as Garner Edwards, which name I think he yet clings to.

In the course of human events, Mr. Edwards passed from the stage of life and went to reap the reward of those who rescue the perishing and support the orphans. After his death, Mr. Edward's sisters, Misses Fanny and Laura, continued to care for the boy, and raised him to manhood. Garner was proud of his family, "and was as faithful as a watchdog, honest at all times, and a great protection to the good ladies who were befriending him, and who were now also alone in the world without parents or brothers. When Garner grew into manhood he did not forsake the home that had sheltered him, but insisted that it was his home—the only home he knew—and that it was his duty and pleasure to aid in supporting it; and he did come to bear a considerable part of its expenses.

Garner learned to be a brickmason, and finally moved to Alabama. He became acquainted with Booker Washington, the great Negro Educator, and the acquaintance ripened into friendship. Washington aided Garner in getting work that would enable him to take a course in the school at Tuskegee and at the same time be self-sustaining. Here as in all other of his positions, Garner made a good record and won many honors. In the meantime he did not forget the folks at home, and his remittances to them were always punctual. After finishing school he married, but continued in the employ of the school and Booker Washington and is there yet.

Sometime ago Miss Laura had a fall and sustained a painful injury which confined her to her room. As soon as Garner heard of it he telephoned to Warren Edwards here to provide the best medical attendance possible, and to supply every want at his expense. Following the telegraph came his wife, a trained nurse, "to take care of his white folks," and she is here yet performing every duty with a devotion seldom witnessed. Garner wanted to come too, very much, but he sacrificed the pleasure to keep his salary doing, "because they might need something."

Garner paid the taxes on the old home for years, but in the meantime he has saved enough to buy him another home in Alabama. No one of any color could have been more faithful and appreciative, and such gratitude and devotion as this humble Negro has shown for his white benefactors is a lovely thing to behold in this selfish day. It is said that he never once presumed anything or forgot his place and the respect due to those around him.294

The following letter and list accompanying it explain themselves:

Beloit, Wis. Dec. 28, 1906.Dear Mr. Washington

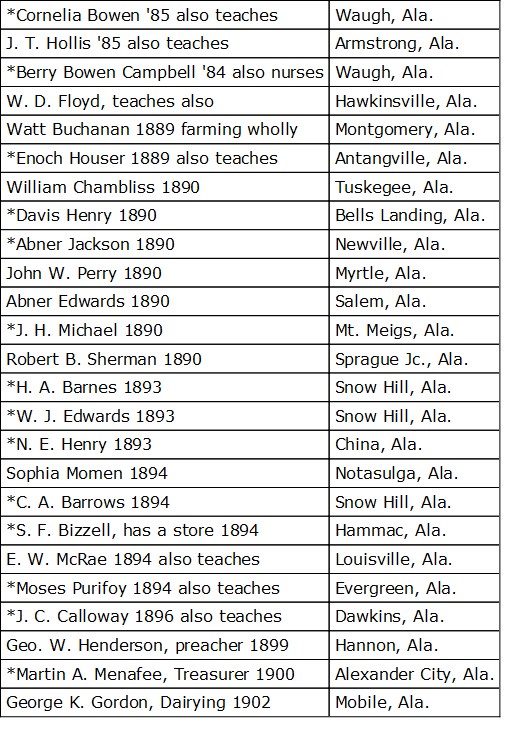

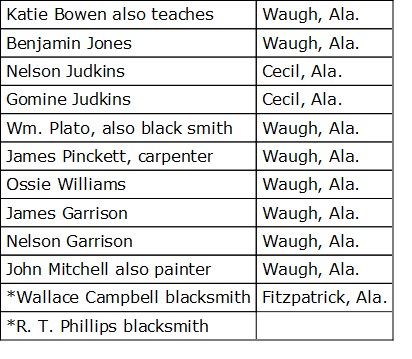

In answer to your telegram for names of graduates and former students engaged in farming in Ala I send the following. I know there are others especially former students but I cannot now recall names. I will try to add to the list if possible.

I would say in regard to the Bowen sisters they have about 600 acres of land and look after the cultivation of it and some parts Cornelia and Katie care for directly actually raising a crop. McRae farmed last year at Louisville, Ala. the year just closing. Mr. W. A. Menafee has 200 acres of land at Alexander City. This he superintendents by two visits each year. Those marked with a cross farm on their own land. Edwards and Barnes own land at Snow Hill which they farm by the labor of others. Whether they and Mr. Chambliss come under the head of farmers according to your idea you can decide.

I leave January 3 for Denmark, S. C. You can write me there till further notice.

Yours(Signed) R. C. BedfordGraduates and Former Students Engaged in Farming in Ala. Wholly Or in Part

This is a letter from a Negro farmer in the south:

Isaac P. Martin—

Merryweather Co—near Stenson

Father belonged to Peter Martin near about 3 miles from where he was born—never did own any land. Went to work planting at 9—Worked 9 to 25—Had six or eight months schooling—Went one month in a year. School lasted about three months. Used Blue Back Speller got as high as Baker; Got as far as subtraction—Did not know anything outside of reading—Did not know what a newspaper was.

Father taught us to work corn, cotton sweet potatoes—He was a – farmer—Had eleven children all worked—about 1880 they began to grow up and leave the farm—go on some other plantation—all married.

My older brother and all the younger children got more schooling Brother next younger—Payne's Institute Ga.—finished preaching in Americus Georgia. I had a cousin to come here—He wanted to buy – here—He was interested in machine shop—He was down in Opelika. He met more boys on their way here, inquiring around to get down this far and get in.

I had saved up $200 in the bank. I was going to buy land. Went into day school a Preparatory about 800 or 900 students. The first work was in harness & shoe shop—Lewis Adams was in charge—I came there walking. I wanted to get away from the farm. Going around town I saw that everyone looked better than on the farm—I wanted to be something. Went in twice a year. We had plenty country churches. Rabbits, squirrels, ducks, possums—Geography, reading, Wentworth's Arithmetic. Miss Hunt and Miss Logan were one of my teachers. I read lots about Hiawatha. There was a number of little boys in the shop—they used to call me "Pop." They were ahead of me. Went to Blacksmith Shop. Worked about four months. Then went to work in Wheelwright. I learn a good deal about blacksmith and wood work. I find both these trade very handy.

I was here three weeks before I could eat in the dining room—had to go to restaurant—I was ashamed.

I was here only one term. Came in 1895—left in 96—Never came back until tonight. My mother sent for me—My mother was awful sick. My class was so low that I was ashamed to come back. I weighed 240 pounds. I went back home until 1898—on farm. I got to read my newspapers. I subscribed for the semi-monthly Atlanta Journal—I could read that.

I saw advertised and so much money paid out for wages—I thought I would go into business. I started grocery store and meat market—I had $2,500 made on farm. Father used to run us off the farm at 20 so I rented some land.

I was born 1870. I had been working for myself for years. 1898 I came to Birmingham. I failed in grocery business. "Credit." I made a lot of friends all over town. ....................................... They had lots of money but they owed a lot. It take lot to feed them. Took three years and little over to get all of money.

Worked for Tenn. Coal and Iron Co. I leased some land from the Republic Iron and Steel Co. Leased 64 acres outside of Pratt City and went to trucking. I bought two mules for $40. It was a sale. They were old run down mules. They were blind—I worked there until I grew something. Farm about a mile from Pretts. Paid $1.50 per acre—now I pay $7. The company would not sell. I peddle vegetables to people here—ran two wagons—now I run three. Got new feed for horses. By fall had lots of stuff. Married in 1900—year after went to Birmingham. Second year I was able to buy two good mules—Had two good wagons made. Fall of second year had another which made three. Running three now. I employ six people—3 men and 3 women all the time. I drive the wholesale wagon.

I raise between $3,500 and $4,000 worth of stuff each year. Have since the second year. I sell about $2,000 a year above expenses. Production increases every year. I learned all I know about trucking since then. I have fifteen head of cattle. Eight milking cows. I raise three crops. That is the highest. Third crop is not worth so much. 90,000 cabbages this year. Got the plants from South Carolina. I bought a piece of land in Oklahoma for $3,000 outside of 22 miles from Muskogee. Land rents now for $300. I own a lot in Red Bird. Have 2 children. 14 & and 17. They go to school.

Won county prize year before last—196 bushels—this year received State prize 200 bushels. Plant eight and ten acres of cotton, 14 acres corn. Raise all my fodder. Three-fourths acres of new sugar cane, 150 gals. of syrup. I make butter $30 per hundred. $40 retail. I take two or three little farm journals and take the bulletin.

These letters addressed to R. E. Park and to Booker T. Washington give information about the estate of John McKee:

Estate of }

John Mckee, }

Deceased. }

Hon. Booker T. Washington,

Tuskegee Institute,

Alabama,

Dear sir:

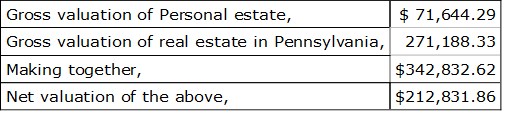

Your favor has been received and in reply thereto I would state that the State Appraiser fixed the valuation in Estate of the late Colonel John McKee as follows:

Of this $46,500. is in unimproved real estate from which, at this time, no income is derived.

In addition to the above the Estate owns the following from which no income (or but a nominal income) is derived:—a lot in Gloucester County, New Jersey, valued at One hundred Dollars ($100),—a large area of land in Atlantic County, New Jersey, known as McKee City, assessed for taxation at twenty-thousand six hundred and fifty Dollars ($20,650) and a tract of coal and mineral lands in Kentucky, which Colonel McKee always considered would turn out to be valuable and would eventually realize a considerable sum. It is assessed for taxation for 1909 at Seventy thousand Dollars ($70,000)—

In brief the testamentary directions of Colonel McKee are to accumulate the rents and income of his estate until the decease of all his children and grand-children, meanwhile improving (under certain conditions) his unimproved real estate. Upon the death of all his children and grand-children, the estate is to be made use of in the establishment and maintenance of a college for the education of colored and white fatherless boys.

Very truly yours,Joseph P. McCullenFebruary 23, 1909.Mr. Robert E. Park,

Tuskegee Institute, Ala.,

Dear Sir:

Yours of the 13th inst., post marked the 16th inst., has been received. You state you would be glad to have any information I can give you about Mr. McKee, particularly in regard to the amount of the estate he left at the time of his death.

The value of Mr. McKee's estate has been variously estimated from $1,000,000 to $4,000,000. I am not able to give a more exact estimate, as I have not seen any inventory made by his executors. He owned more than 300 houses in this city, all unencumbered. He also owned oil and coal lands in Kentucky and West Virginia, and lands in Bath and Steuben Counties, N. Y. As to his personal characteristics, I would suggest that you see the Philadelphia Press of April 20, 1902. If you desire a more exact estimate of the value of his estate, I would suggest that you write Joseph P. McCullen, Jr., No. 1008 Land Title Building, this city.

Yours truly,T. J. Minton.The following letter from Colonel James Lewis to Booker T. Washington gives valuable information about Thomy Lafon and incidentally about other persons in New Orleans:

New Orleans, La., Jany. 25/09.Colonel James Lewis,

Dear Sir:

In answer to your letter of 14th instant, will say that the delay in my answer was caused by my desire to obtain and furnish to you all informations regarding the late Mr. Thomy Lafon.

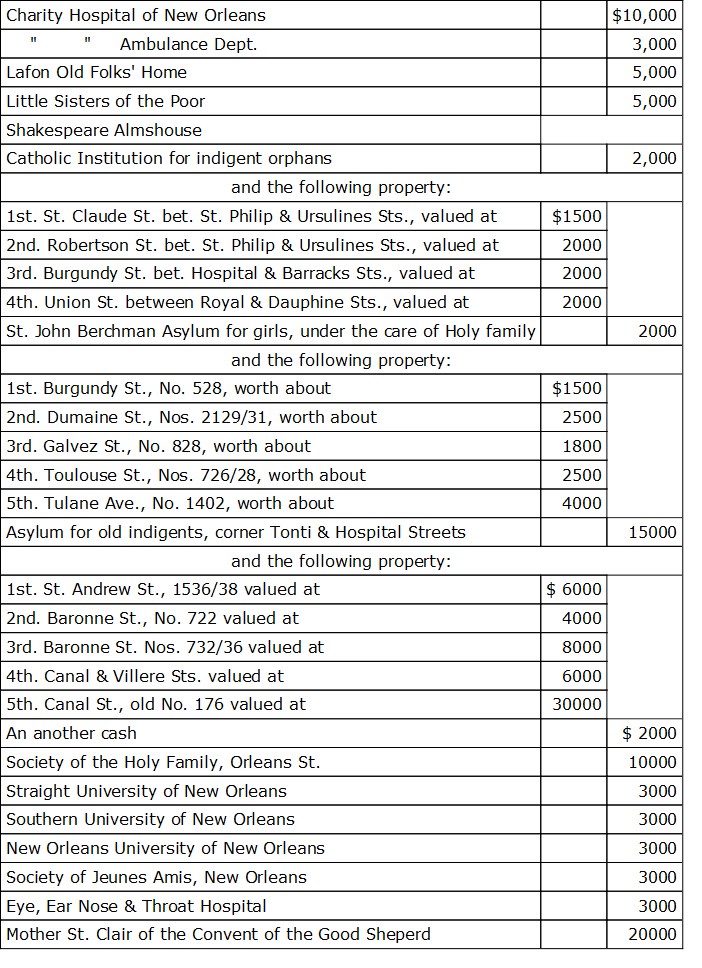

The baptismal records in the archive of the Cathedral at that time written in Spanish attest that the late Mr. Thomy Lafon was born in this city on December 28th, 1810. He died at his home, corner Ursulines & Robertson Streets, on December 23rd, 1893, at the ripe age of 83 years. His body rests in the St. Louis cemetery on Esplanade Avenue. He was a man of dignified appearance and affable manners. In early life he taught school; later he operated a small dry goods store in Orleans Street until near into 1850. He was never married. Sometime before the war of Secession he had started his vast fortune by loaning money at advantageous rates of interest and by the accumulation of his savings. Toward the close of his career he became attached to the lamented Archbishop Janssens and began his philanthropies. By the terms of his will, dated April 3rd, 1890, he provided amply for his aged sister and some friends, and wisely distributed the bulk of his estate among public charitable institutions of New Orleans. His legacy was appraised at $413,000.00 divided in securities and realty.

In recognition of his charity, the City of New Orleans, named after him one of its public schools.

Before his death he had established an asylum for orphan boys called the Lafon Asylum, situated in St. Peter Street between Claiborne Avenue & N. Derbigny Street. To this Asylum he bequeathed a sum of $2000, and the revenues, amounting to $275 per month of a large property situated corner Royal & Iberville Streets.

Other legacies were to the

All of which cash legacies were doubled.

Yours respectfully,(Signed) P. A. BacasBOOK REVIEWS

The History of the Negro Church. By Carter G. Woodson, Ph.D. The Associated Publishers, Inc., Washington, D. C. 1921. Pp. 330.