Полная версия

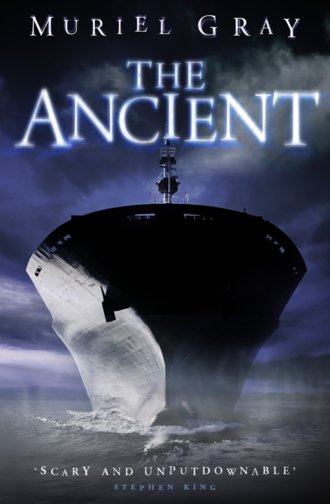

The Ancient

MURIEL GRAY

The Ancient

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Muriel Gray 2002, 2015

Cover photograph © Stewart Sutton/Getty Images; Shutterstock.com (sky, sea, mist)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Muriel Gray asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008158262

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780007404438

Version: 2015-10-29

For

Hamish, Hector, Rowan and

Angus James Barbour, with love

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also By Muriel Gray

About the Publisher

1

In other circumstances, Eugenio might have given the rat a name. Rats, and the bold rats of this sun-baked slum more than most, were hard to capture. He might have kept it under a crate and thrown it pieces of food, simply to be its master, to control it, to confine it, the way his own life was determined by pinched-faced adults.

But this rat was to die. It was their sacrifice, and as such, it needed no name.

The creature writhed and thrashed in the soiled canvas bag that Eugenio held out from his body. His two companions watched, eyes big in anticipation, waiting for their leader, their priest, to guide them.

As the oldest at nine years of age, Eugenio felt the weight of that responsibility: he moulded his face into an expression of suitable solemnity as he kicked at a piece of hardboard in the rubbish.

‘Here.’

The two smaller boys glanced at him, then went to work, pulling the wood from the malodorous pile, farmers lifting a diseased crop from a toxic field. This slowly-shifting glacier of garbage was their home, their playground, their store cupboard. The fetor had long since ceased to make any impact on their senses, nor did the uniformity of its colour and texture, a mosaic of greys and primary hues, fill them with despair. They were the naturalized creatures of this place and the stained Nike T-shirts they wore ticked them with approval.

The board was extricated and positioned at the mute head-nodded directions of Eugenio the priest. He squinted at the sun to check its position and was satisfied.

Both boys knew what to do. The smaller took the awful thing, the thing none of them wanted to touch, from his plastic carrier bag and laid it carefully in the centre of this makeshift altar, while the other unsheathed the salvaged hunting knife.

Eugenio glanced at the doll, if anything so repugnant could be described as a doll. Its head was formed from the skull of rat, which had been stitched onto the leather body by means of a strap through the sockets, onto which two black orbs of cloudy stone had been glued to mimic eyes. Below it, tiny irregular tin teeth had been meticulously embedded into the yellowed bone, bestowing a manic grin upon the skull that was worse than the grimace of any corpse. It topped a grotesque torso, worn shiny leather that described a bulbous belly, gashed open and stitched back with the same loving craftsmanship as the head attachment. There was a cavity inside, open and ready to receive their sacrifice. It was ovoid like a recently-vacated womb, hardened and blackened from previous offerings, and the scabbed interior gave the slit womb an authenticity as though any baby’s exit had been a bloody and fatal one. But if the figure was meant to be female, then the horrifically-oversized leather penis that hung obscenely between its legs was a strange contradiction. The arms and legs were thin, reptile-like, too long for the squat body; but the worse aspect of their fragility were the long, serrated shards of metal, like broken claws, that completed each limb.

Eugenio began to feel nervous. If his aunt discovered that he had taken this figure from her few possessions she would make him suffer. Her rage was always contained and deadly, and he swallowed at the idea of what she might do. But she would not know. The ceremony would be over in minutes and if successful, would grant him the power that would make even her spite meaningless. His greatest fear was that it wouldn’t work. His knowledge was patchy, only a tiny portion of what his aunt and her clients discussed in their drugged ramblings. The rest he was going to invent. Somehow he felt sure that improvisation would suffice. The power of the ceremony after all, he had convinced himself, was in the intention, not the vocabulary.

Tiny as it was, it took all three of them to hold the rat down as Eugenio sliced through its filthy fur. It bared its teeth and piped its agony in a series of shrill screams that fascinated the boys as they worked. They heard rats fight all the time, but the piercing, high-pitched squeals that accompanied those scuffles, so high they operated on the very edge of human hearing, were quite unlike this. These protestations were guttural, having a power that defied the small lungs that expelled them, and secretly, Eugenio enjoyed the sound. He hated rats. They crawled on him at night, pissing on his blanket, boldly feeding on the scraps of food that were never cleaned from the hard-packed earthen floor of his family’s shack. Now here was fitting revenge.

Delicately Eugenio sliced out the beating heart and pincered the ludicrously tiny organ between thumb and forefinger, quickly transferring it to the leather slit, poking it into place with a bloody finger and wiping his hand unconsciously on the side of his shorts.

Three pairs of eyes darted between each other’s faces then closed in reverence.

Eugenio cleared his throat and began to speak with a curious mixture of the self-consciousness of a young boy, and the gravitas of a priest.

‘Fallen One – whether male or female, at any rate commander of heat and reproduction, being one who even with his spittle can work sorcery – where art thou?’

He opened his eyes and looked at the now-still heart in its leather nest, but the figure’s empty eye-sockets stared past him into space, oblivious to the gift in its belly. Eugenio closed his eyes again, this time screwing them tightly shut as though the effort would increase his potency.

‘I shall be seen by thee, and thou wilt know me. Would that thou were not hidden from this son of thine. Eat of this sacrificed heart, and also of the one still beating in the body of thy servant.’

He stopped. This was as much as he had memorized from his aunt. From now on the quality of the prayer would plummet. He would have to make it up. His saliva dried, both from the tension of what he desired to happen, and the terror of looking a fool in front of his companions.

‘I am … no one. You … thou … are eternity. We want you to come to us … and to give us power to … do many things.’

One of the boys opened his eyes and looked across at his leader. The change in tone had not gone unnoticed. Eyes still closed tightly, Eugenio continued undaunted.

‘Come to us now, as you have come to others before us. As you have come to the older ones before the Spanish came.’

He opened his eyes and saw that his entire congregation of two were now staring at him.

He stared back defiantly, then let his eyes drop to the useless, static doll, and the flat-furred husk of the rat, mottling the already-stained hardboard altar with its thick, poisonous blood.

A terrifying and powerful bellow broke the silence, and the three boys jumped in fright.

There was a brief moment of confusion, a moment in which they believed the Fallen One had answered them with that fearsome bestial noise, and then their inbred survival instincts processed the information and made them scatter like rats themselves. There was trouble approaching. But not of the supernatural kind. In seconds they had disappeared.

Their hurried departure knocked the altar at an angle, and the figure flopped over, slowly letting its tiny prize slither onto the wood and down into the trash.

The shout was repeated, but this time it was followed by a sharp laugh from another source. Scrabbling in the rubbish like a runner in sand dunes, a youth burst over the short horizon of plastic bottles, car tyres and old mattresses.

His face was contorted with fear, his mouth a black downward crescent of horror, as he stumbled across the unforgiving terrain like a drunk. Close behind came two men, running, but with less urgency, the broader of the two allowing a gun to dangle casually from his hand.

Anything could have tripped the runner; a piece of metal lying beneath the cartons and rotting vegetable matter; a rope tangled in the mesh of discarded chicken wire; a broken drawer from a chest protruding from the sea of trash like a dorsal fin. But it was actually the hardboard altar that snagged the pursued man’s foot, and sent him slapping into the undulating mush with a soft, revolting thud.

His assailants slowed then approached him with party smiles, while the fallen youth stayed face-down in the trash, shoulders heaving, hands closing on discarded newspapers and coffee grounds.

There was no dialogue, no conferring or taunting. The man with the gun in his hand swivelled his limp wrist and shot the youth through the back of the head.

It was a gun without the benefit of a silencer. The sharp crack reverberated shamelessly through the still afternoon. Both men looked around like lions after a kill. Not afraid, nor guilty, but bored, indifferent, blank.

No resident of this filthy colony would come to investigate. No policemen would gallop to a chase. In this landscape they were the law. They had the gun. The smaller of the two men bent down and fumbled in the dead youth’s jacket until he had retrieved the tightly-packed plastic envelope of white powder that had sentenced him to death.

Even then, there was no conversation, their companionship being the company of animals, dumb and cunning at the same time.

They turned to go, and as though some primitive electrical connection had been made in his brain to remind him of his last deed, the executioner turned back and spent one more bullet on the corpse.

This time the trajectory took it through the very top of the skull. He watched for a beat with satisfaction as the back of the head burst off and a dark black and grey mess oozed from the splintered head. Then he turned and followed his companion.

The leather doll lay on its side mere inches from the dead youth’s head, its impassive features regarding the remains of the human like a satisfied lover. Eugenio’s aunt would take her time in punishing the nephew who stole from her when she discovered that the doll had gone. It was old. Very old. She treasured it as nothing else, harbouring sick and atavistic fantasies about what it might do for her tragic life if she could unleash its rumoured power.

For Eugenio would not retrieve it.

Because as only the confused flies that had settled to sup on the viscous meal before them, and the blazing indifferent sun above witnessed, the impassive handstitched abomination began to shift slightly. Slowly and almost imperceptibly at first, its limbs began to be drawn down into the garbage. Not naturally, the way an object may shift and settle with gravity, but like prey caught by something unseen. In a matter of seconds the doll had drowned and was gone down into the trash – along with its still companion.

As the two figures, man and leather, sank beneath the fetid surface, it was only a matter of minutes before the burst video tapes and toilet paper, the mashed cloth and food remains, had joined once again to make a new skin over their secret and buried possession.

2

Just one short glimpse was all the dusty window afforded, but it was enough to confirm she was too late. Esther Mulholland wiped the glass with the flat of her hand, as if smearing more grime across the bus window would somehow make it not true. But it was true. The dock had revealed itself briefly between a low warehouse and some shanty huts and there, silhouetted against a glittering late-afternoon sea were four ships, none of them the one she had the ticket for.

She leant her head against the window and quickly removed it again as the bus dived into a pothole, shaking her bones and battering her forehead against the glass. The woman beside her, who had been nursing a fat, scabbed chicken on her lap for the entire journey, cackled and nodded a toothless grin at the bus in general as though it were somehow obeying her command. Esther had been watching her with fascination for the last five hours, amused as the wizened, squat old woman somehow anticipated the chicken before it shit, opening her legs at just the right time to let the startled beast squirt onto the floor beneath her.

The chicken, Esther reasoned in her most bored moments, must tense its muscles before taking a dump, allowing the woman who cupped it in her callused hands to feel its contortions and take action. But whereas this had been a charming diversion a hundred miles back in the stony monotony of the Peruvian countryside, now it was irritating her. The smell of the baking chicken shit on the floor and the musky reek of unwashed human flesh, which very much included her own, was making her stomach contents shift.

Unless that container ship was hiding, and it was unlikely that 150,000 tonnes of metal could achieve such a trick, then she was well and truly stranded.

It had sailed, and with it had gone her only means of getting home. It wasn’t like Esther to be irresponsible. The diversion to the temple in Lacouz had cost her only five days, and she had calculated she would make it up on the journey back from Cuzco. And she would have done, had it not been for the curious, infuriating thing that had happened in the shanty town where she’d camped overnight to wait for the bus.

Esther had become aware, quite gradually, that a small Peruvian man, a peasant from the plateau, judging by his dress, had been following her all day, staring. He was there outside the tiny store where she bought mineral water and biscuits for the bus journey. He was there when she packed up her tent, standing a short distance away, his gaze unflinching. And he was there, gazing from the other side of the dirt road, when she sat in the shade at the side of the road, her back against a cool stone wall, waiting for the one and only weekly bus to Callao. She was used to being stared at by people the further she had strayed from the cities, but this was different. He was not looking at her with that naked and childlike curiosity natives have for foreigners. His was the stare of someone who was waiting for something. She’d tried waving, acknowledging his presence, but he’d merely continued to look. Esther had been getting freaked by it, and was glad to be leaving the town. But as she sat against that wall, she’d decided to meet his eyes and stare him out. All she remembered now was that his eyes had been slits as he screwed them up against the sun, and yet as she stared at him, she still felt the intensity of their scrutiny. She had felt her own eyes growing heavy, and that was simply all she could recall. When she’d woken up, her head slumped forward on her chest, her neck agonizingly cramped, the man was gone, and more importantly, so was the bus.

Her fury at her idiocy was incandescent, but pointless. There had been nothing for it but to wait it out for another week. And so here she was, seven days late, but at least she’d got here.

The optimistic part of her had thought that maybe the ship would be late leaving, that maybe the kind of luck a girl her age took for granted would hold out. But quite clearly it hadn’t, and the truth was, she was stumped, stuck in the nightmarish industrial port of Callao with a non-refundable ticket for a ship that wouldn’t be back this way for over a month.

Her fellow passenger opened her legs to let the chicken shit again, and Esther closed her eyes. Options. As long as you were alive, breathing, talking and walking, there were always options. She held that thought, but on her own chicken-free lap her hands made fists as if they knew better.

The bar didn’t have a sign outside because it didn’t have a name. It was housed in a metal shed that had once served as the offices of a coal-shipping merchant. Then it might have had desks, angle-poise lamps, piles of documents, calendars on the walls, fax machines and wastepaper bins. Now it was simply a shed. Running parallel to one wall was a long L-shaped wooden board nailed to metal trestle legs that created a crude barrier between the clients and a poverty-stricken gantry of a few greasy bottles of spirits and crates of unrefrigerated beer. On the wall a small portable TV was attached to a metal bracket. Its flickering images fought against the broad shafts of sunlight that filtered from high slits of windows, light that was made solid by the thick fog of cigarette smoke. A coat-hanger aerial stuck on with duct tape accounted for the snowy, hissing reception of the Brazilian game-show that was being watched by the occupants of the shed. Esther had time to take in these figures before they registered her quiet entrance, and it did nothing to lift her spirits.

About a dozen men slumped forward from the hip across the wooden bar, their positions so similar they could have been members of some obscure formation team. Each held a cigarette in one hand, the other cradling a drink, and their heads were uniformly tilted up to stare at the glow of the TV. The barman’s position was in exactly the same aspect, but in mirror image. Even though his body was facing Esther, his head was twisted to watch the screen and he failed to notice her entering until the cheap double plywood door banged dramatically back on its hinges. But the pause had given her time to locate what she’d come in for, and without catching the man’s eye Esther strode as purposefully across the room as her massive back-pack would allow to the wall-mounted telephone. There was only a one-hour time difference in Texas. She pictured exactly what Mort would be doing right now as she waited for the Lily Tomlin-impersonating AT&T woman to connect her.

Of course he would let the phone ring as long he could. His chair would be on its back two legs, leant against the wall of the trailer where he could monitor the residents of Selby Rise Park from the long window above his desk, and keep a doting eye on his ugly mutt tethered to a stake by the door as it barked at friend and foe alike. He would have a cheroot between his rough lips and a bottle of beer in his fist, and there was nothing on this earth that would make him take a call collect from Peru or anywhere else.

‘No reply, caller.’

Esther scratched at the wall with a finger nail.

‘He always takes a long time to answer. Can you give it a few more rings?’

The operator made no reply and Esther was about to hang up, assuming the call was terminated, but a few seconds later she heard the connection being made. It was weird hearing Mort’s voice so far away, a voice that belonged in another world.

‘Yeah?’

‘AT&T. I have a call collect from Callao, Peru, from Esther Mulholland. Will you accept?’

‘What?’

‘I have a call collect …’

‘Yeah, yeah. I got the stingy bastard call collect bit, sweetheart. Where the fuck you say it’s from again?’

There was a pause as the operator pondered whether to hang up on the profane recipient or not, and then she said curtly, ‘Peru. South America.’

‘No shit!’

Esther heard him chuckle.

‘And it’s Benny Mulholland’s girl, you say? The one without the fuckin’ dimes?’

‘Will you accept the call?’

‘Huh? Like all of a fuckin’ sudden I’m an answerin’ service for her old man? Tell her to send a fuckin’ postcard.’

He hung up. The operator cleared her throat. ‘I’m sorry, caller. The number will not accept.’

‘I gathered. Thanks.’

Esther put the phone down gently. She had absolutely no idea why she’d made that call. Even if a miracle had happened and Mort Lenholf had taken her call, what did she expect him to do? Benny would be blind drunk by now, asleep in the green armchair in front of a blaring TV. Mort could hammer on Benny’s trailer door as long and hard as he liked but she knew it would take a sledge hammer to the kneecap even to make him stir. And the thought of her dad being able to help out in a situation like this was equally ludicrous. Benny Mulholland had probably just enough cash left from his welfare cheque to get ratted every night until the next one was due.

He wasn’t exactly in a position to call American Express and have them wire his daughter a ticket home. She decided she had simply been homesick. Only for a moment, and only in a very abstract way, since home was ten types of shit and then ten more. But it had been an emotion profound enough to want to make contact, and now it left her feeling even more bereft than before. Despite having been to the most remote and inhospitable corners of Peru on everything from foot to mule, it was the first stirring of loneliness she’d felt in the whole three months of travelling.

Esther sighed and turned back into the room. The formation team of drinkers were now all looking her way. The men, although similar in posture, were varied in nationality. A handful were obviously Peruvian, their faces from the unchanged gene pool that could be seen quite clearly on thousand-year-old Inca, Aztec and Meso-American sculpture. Stevedores by the look of their coveralls, and not friendly.