Полная версия

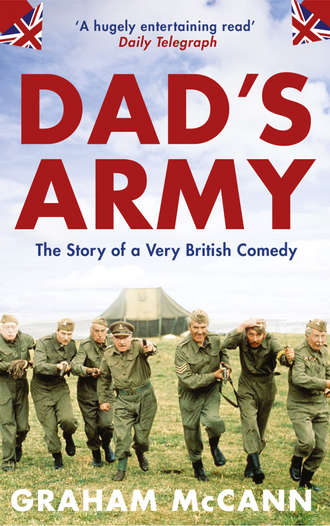

Dad’s Army: The Story of a Very British Comedy

He’d been very good, very funny, and he was a lovely, gentle character. He looked right, sounded right. I was a bit worried about him because I think he was already 72 when I first interviewed him for the part. I’d said, ‘I don’t think I can save you from having to run about a bit now and then. Are you up for it?’ And he’d said, ‘Oh, yes, I think I’ll manage.’ As it turned out, of course, he couldn’t, but we got an enormous amount of capital out of helping him on to the van and things like that, you know. So he turned out to be a very successful character.38

Casting Dumfries-born John Laurie as Private Frazer had been another one of Michael Mills’ suggestions. Laurie, who at 71 was Ridley’s junior by a single year, was a hugely experienced actor: he had played all of the great Shakespearean roles at the Old Vic and Stratford, and appeared in a wide range of movies, including two directed by Alfred Hitchcock – Juno and the Paycock (1930) and The 39 Steps (1935) – three by Laurence Olivier – Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948) and Richard III (1954) – and four by Michael Powell (the most notable of which was The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, in which he played the ever-loyal Murdoch), as well as one starring Will Hay – The Ghost of St Michael’s (1941). He had been working intermittently on television since the mid-1930s, but it had only been since the start of the 1960s that he had begun appearing on a relatively regular basis (first as thriller writer Algernon Blackwood in Associated-Rediffusion’s 1961 Tales of Mystery, and later as Dr McTurk in the 1966 TVS children’s science-fiction series The Master, as well as several cameo roles in both The Avengers and Dr Finlay’s Casebook). David Croft was well aware of what Laurie could do – he had worked with him before in a 1965 episode of Hugh and I,39 and had every faith in his ability to flesh-out the still-skeletal figure of Frazer – but was apprehensive about the actor’s reaction to such an under-developed character:

‘Frazer’, at that time, was described in the script simply as ‘A Scotsman’. It can’t have been very inspiring to such an experienced actor. Michael Mills said, ‘Make him into a fisherman.’ So Jimmy and I made him into a fisherman for that first episode. No use to us at all, of course, as a fisherman never went out to sea in those days because it was the invasion coast. Later on, we started allowing him to make coffins in his workshop, and that developed into him becoming the undertaker – and then he became very useful indeed, a marvellous character. But we did find it difficult, at the start, to write for him, as this ‘Scottish fisherman’, and I doubt that John was too impressed either.40

Laurie, sure enough, was far from impressed, but he had a policy of never refusing offers of work, and so he agreed, somewhat reluctantly, to play a character whose lifetime he confidently expected to last no longer than six half-hour episodes.

James Beck was a far more willing recruit. The 39-year-old actor from Islington had been working extremely hard at establishing himself on television since the start of the 1960s – following a formative period spent in rep at York – but had not yet succeeded in securing a regular role in a significant show. At the end of 1963 he had written a typically polite letter to Bush Bailey, the BBC’s assistant head of artists’ bookings, asking if there was any chance of an interview (‘as I don’t seem to be making a great deal of headway’).41 Bailey did see him early the following year, and filed a favourable report, but nothing tangible came of the meeting except for more of the same old bits and pieces. By 1968, most viewers would have glimpsed him at some time or other in the odd episode of such popular police drama series as Z Cars, Dixon of Dock Green and Softly Softly, or in a one-off role in a situation-comedy such as Here’s Harry, but few could have put a name to the face. The prospect of a major role in a new show such as Dad’s Army, therefore, was precisely the kind of opportunity that Beck had been waiting for. Playing a spiv actually represented something of a departure for an actor who had grown used to being cast as characters on the right side of the law: even in his two previous appearances in Croft situation-comedies he had played a police constable on the first occasion and a customs officer on the second.42 As someone who had grown up in the same working-class environment that had (with more than a little help from capitalism and rationing) formed such ambiguous characters, and also as a great fan – and gifted mimic – of Sid Field, it was a departure that Beck relished. ‘He was obviously a talented actor,’ Croft recalled. ‘He just came to me, in fact, in an audition. I had used him before, and I fancied him very much for that particular part. There weren’t any other real competitors for it – except Jimmy, of course, and we’d already ruled him out – so casting Walker turned out to be one of the easiest ones of the lot.’43

Ian Lavender had Ann Callender to thank for the part of Private Pike. Lavender – a 22-year-old, Birmingham-born actor whose fledgling career up to this point consisted simply of two years in drama school at Bristol’s Old Vic followed by a six-month season playing juvenile leads at Canterbury’s Marlowe Theatre – had recently become one of Callender’s clients, and early in 1968, just before he was due to make his television debut on 5 March in a one-off ITV/Rediffusion drama called Flowers At My Feet, she urged her husband to watch him. ‘So I did,’ recalled Croft, ‘and I was most impressed. He played a young juvenile delightfully.’44 Croft had no qualms, as a BBC producer, about casting one of his wife’s clients, partly because he had great faith in her – as well as his own – judgement, and partly because he already had the BBC’s blessing to go ahead and do so:

I’d had a considerable number of interviews at this time with Tom Sloan, because of the fact that my wife was an agent. I said, ‘Tom, look: we’ve got this corporate situation – my wife’s an agent, she’s got some good clients, but, at the same time, I don’t want to use them if somebody is going to say, “He uses his wife’s talent all the time.”’ So he said, ‘Well, no, you mustn’t not use them, David; you must also forbear to use them when somebody else of superior ability is available. But you must not deny her actors a chance for employment.’ And that was fine; that was settled. He did go on to say, ‘When you do use somebody in your wife’s list, just drop me a note’, which I always did.45

When Callender called Lavender with the news that he was wanted at Television Centre he had no idea that the man to whom she was sending him was her husband:

I was just sent along to see this man Croft. About a situation-comedy called Dad’s Army. It was a bit terrifying, really, because at drama school I’d been playing Romeo and Florizel and all that sort of thing, and the only comedy I’d ever done was Restoration Comedy. I knew about the Home Guard, because my father had been station sergeant at a police station that served the Austin motorworks in Birmingham, and he’d had to go and inspect them and make sure they were doing everything right, so I knew what it was. But the thought of being in a comedy – I did find that daunting. Anyway, I went and read for David. Then I was called back again the following week, and then again at the end of the week after that. And then I heard I’d got the part.46

It was only after he had been hired that Lavender discovered just how well-connected his agent actually was:

Ann Callender said to me, ‘I’m going to take you out to lunch, darling.’ Which she did. And she said, ‘By the way, I forgot to tell you that David Croft is my husband.’ And my face obviously dropped, because then she said, ‘Yes. That’s exactly why we didn’t tell you. But you got the part because he wants you. And I’d just like to point out – don’t forget that he can always write you out!’47

Once Pike had been picked, Croft turned his attention to the supporting players. John Ringham, an experienced, self-styled ‘jobbing character actor’,48 was chosen to play Private Bracewell, the Wodehousian silly ass from the City; Janet Davies, a bright, reliable performer whom Croft had used in a recent episode of Beggar My Neighbour, was hired as Mrs Mavis Pike;49 Caroline Dowdeswell was recruited to play junior clerk Janet King (a hastily drawn character introduced after Michael Mills had declared that the show needed a soupçon of sex);50 Gordon Peters, a former stand-up comic who specialised in playing Hancock-style characters, was drafted in for the one-off role of the fire chief; and several seasoned professionals – including Colin Bean, Richard Jacques, Hugh Hastings, George Hancock, Vic Taylor, Richard Kitteridge, Vernon Drake, Hugh Cecil, Frank Godfrey, Jimmy Mac, David Seaforth and Desmond Cullum-Jones – were engaged (at six guineas each per episode) to make up the platoon’s back row.51 One character now remained to be cast: the nasty, nosy, noisy ARP warden.

Croft thought more or less immediately of Bill Pertwee. Pertwee, in real life, could not have been less like the loud and loutish character Croft and Perry had created to darken Mainwaring’s moods, but he was quite capable of investing such a role with a degree of comic vulnerability that would lift it far above the realm of caricature. Like his cousin, Jon, Bill Pertwee came to television after learning his craft both in Variety – first as a colleague of Beryl Reid, later in partnership with his wife, Marion MacLeod – and radio – as a valued and versatile contributor to both Beyond Our Ken (1958–64) and Round the Horne (1965–7). After catching the eye in a series of The Norman Vaughan Show on BBC1 in 1966, he found himself increasingly in demand not only for comic cameos but also as a warm-up man for various television shows, and he started to think more seriously about pursuing work in the medium ‘to add another string to one’s bow, as it were’.52 In 1968, just as he was preparing for a season of performances at Bognor Regis, he heard from David Croft:

I’d worked for David the previous year. It was just a small part in an episode of Hugh and I with Terry Scott and Hugh Lloyd: I’d only had a couple of lines, but I had to shout at Terry Scott and push him around a wee bit in a cinema queue. That must have stuck in David’s mind, because when he was casting Dad’s Army he rang up the agency I was with [Richard Stone], found out that I was probably available and gave me a call. He said, ‘I’m starting a programme about the Home Guard, and I’ve got these couple of lines for an air-raid warden. You just come into an office and shout a bit and then go out again.’ And that was it – that was how he cast me in that.53

Even though the air-raid warden was not, at that stage, conceived of as a regular character, Croft knew that Pertwee could be relied on not only to turn in the kind of spirited performance he required to test the role’s comic potential, but also to inject some welcome energy and good humour into a company of tough and occasionally testy old professionals. ‘I booked Bill because he was good, of course, but I also booked him in order to keep everyone else happy and sweet. He was always very bubbly, very well liked by everyone, and he’s marvellous fun.’54

The casting, at last, was complete, and Croft regarded the ensemble that he had assembled with a considerable amount of satisfaction: ‘The cast that you started out thinking about is never the same as the one you finish up with, but I was pretty pleased with the line-up we’d managed to get. There was a great deal of quality there.’55 He looked ahead at all the potential clashes of egos, all the possible conflicts of ambition, all the inevitable accidents (happy and otherwise), all the long drawn-out set-ups and last-minute revisions, all the budgetary worries, all the problems with props and people and performances, and he could not wait to get started. He was ready to make a television programme.

THE COMEDY

There’s nothing funny on paper. All you are playing with is a bagful of potential. Even when the show’s written you haven’t got anything. Comedy is like a torch battery – there is no point in it until the circuit is complete and the bulb, which is the audience, lights up. It is how strongly the bulb lights up which determines how well you have done your job.

FRANK MUIR1

CHAPTER IV The Pilot

You put your head on the block every time you televise comedy, for everybody in the audience is an expert in a way that they never are with drama.

DUNCAN WOOD1

It’s folly – sheer folly!/I never doubted you could do it!

PRIVATE FRAZER2

The atmosphere, according to Jimmy Perry, was ‘very tense’3 on the chilly morning at the end of March 1968 when the cast came together for the first time. In those days, before the construction of the BBC’s own rehearsal rooms in North Acton, programmes were prepared in a wide variety of unlikely-looking venues secreted among London’s least alluring nooks and crannies, and, in the case of Dad’s Army, the site for the initial read-through was a stale-smelling back room of The Feathers public house in Chiswick. Here, seated side-by-side around a large mud-coloured table, were the actors whose task it now was to bring the inhabitants of Walmington-on-Sea into life. ‘I looked at that motley crew,’ remembered Perry, ‘and I thought to myself: “This is either going to be my biggest success or my biggest failure – it all depends how they get on.”’4

Some of them – such as Clive Dunn and John Le Mesurier – were old friends; others – such as Arthur Lowe and Arnold Ridley – were merely vague acquaintances; and a few – such as James Beck and Ian Lavender – were total strangers. David Croft took all of the nervy uncertainty in his stride – he was used to the awkwardness of these occasions – but Jimmy Perry could not help scrutinising every look, every nuance, every mild little moan and over-loud laugh for portents of good days or bad days to come. His spirits sagged when John Laurie turned to him and said in a voice of casual menace, ‘I hope this is going to work, laddie, but to my mind it’s a ridiculous idea!’, but later, during a coffee break, they were revived when Bill Pertwee came over and assured him that the show was ‘going to be a winner’.5 He remained, nonetheless, over-sensitive and apprehensive; this had been his big idea, his personal project, and now it was set to be tested.

Preparations had certainly been thorough. David Croft was determined to make the programme seem as true to its period as was humanly possible. Any line that sounded too ‘modern’, such as ‘I couldn’t care less’, was swiftly removed from the script. The services of E. V. H. Emmett, the voice of the old Gaumont-British newsreels from the 1930s and 1940s, were secured to supply some suitably evocative scene-setting narration. Two talented and meticulous set designers, Alan Hunter-Craig and Paul Joel, were brought in to create a range of believably 1940s-style surroundings, and, after researching the era at the Imperial War Museum, they either found or fabricated the right kinds of food – Spam, snoek, dried egg, fat bacon pieces, rabbit, potatoes, cabbages and carrots – brands – Camp coffee, Typhoo tea, Bird’s custard, Brown’s ‘Harrison Glory’ peas, Porter’s ‘Victory’ self-raising flour, Orlox beef suet, Horlicks tablets, SAXA salt, Sunlight soap, Craven ‘A’ cigarettes – furniture – elderly desks, ‘utility’-style shelves, sideboards, cabinets – portraits – of the King and Queen, and Churchill (‘Let Us Go Forward Together’) – and posters – bearing such advice as ‘Keep it under your hat’, ‘Hitler will send no warning’ and ‘Keep it dark’ – to ensure that every home, hall, bank and butcher’s shop in Walmington-on-Sea would reach the screen reflecting a richly authentic wartime look. Sandra Exelby, an accomplished BBC make-up specialist, developed a variety of period hairstyles and wigs, while George Ward, the costume designer, searched far and wide for genuine LDV and Home Guard brassards, badges, boots, uniforms, respirators and weapons, ordering what other outfits were needed from Berman’s, a London costumier (and he made a point of having Captain Mainwaring’s uniform made from out of a slightly superior quality material in order to reflect the higher salary he would, as a bank manager, have received). Someone even managed to find an old pair of round-rimmed spectacles for Arthur Lowe to wear.

‘It had to look right,’ Croft confirmed, ‘and, of course, people had to be able to really believe in the characters.’6 Both he and Perry had worked hard to provide each major character with a plausible past – Jack Jones, for example, had been given a long and elaborate military career (which went all the way from Khartoum, through the Sudan, on to the North-West Frontier, back under General Kitchener for the battle of Omdurman, the Frontier again, then on to the Boer War and the Great War in France) to lend more than a little credence to his regular rambling anecdotes. Each actor was encouraged to draw on any memories which might help them to add the odd distinguishing detail (John Laurie remembered his time as a Home Guard in Paddington – ‘totally uncomical, an excess of dullness’ – and found an easy affinity with Frazer’s strained tolerance of ‘a lot of useless blather’).7

The theme song was Jimmy Perry’s idea. ‘I wouldn’t call myself a composer,’ he explained, ‘I’d call myself a pastiche artist. My aim is to write something that makes you know, as soon as the show starts, exactly what it’s going to be about. For Dad’s Army, I wanted to come up with something that took you straight back to the period and summed up the attitudes of the British people.’8 His lyrics, when they came, could not have seemed more apposite:

Who do you think you are kidding, Mr Hitler

If you think we’re on the run?

We are the boys who will stop your little game.

We are the boys who will make you think again.

’Cause who do you think you are kidding, Mr Hitler

If you think old England’s done?

Mister Brown goes off to town

On the eight twenty-one

But he comes home each evening

And he’s ready with his gun.

So who do you think you are kidding, Mr Hitler

If you think old England’s done?9

Everything about these words – their polite defiance, their frail ebullience, their easy grace – belied their belated origin. ‘I was very proud of it,’ Perry admitted.10 He composed the music in collaboration with Derek Taverner, whom he had known since their time together in a Combined Services Entertainment unit in Delhi, and then resolved to persuade Bud Flanagan, one of his childhood idols, to perform the finished song. Flanagan (along with his erstwhile partner, Chesney Allen) was still associated firmly and fondly in the public’s mind with such popular wartime recordings as ‘Run, Rabbit, Run’ and ‘We’re Gonna Hang Out The Washing On The Siegfried Line’, and his warm and reedy voice was the ideal instrument to age artificially this new ‘old’ composition. Fortunately, although the 72-year-old music-hall veteran was not in the habit of recording songs that he had not previously performed, he agreed, for a fee of 100 guineas, to supply the vocal. On the afternoon of 26 February 1968, he arrived at the Riverside Recording Studio in Hammersmith and, to an accompaniment from the Band of the Coldstream Guards, he proceeded to sing: ‘Who do you think you are kidding, Mr Hitler … ’ Jimmy Perry, standing at the back of the production booth, was visibly thrilled: ‘It sent a sort of shiver up my spine. What a moment! To think that dear old Bud Flanagan, whom I’d sat and watched as a kid up in the gallery at the Palladium, was right there now, singing a song that I’d written. Marvellous!’11 After eight takes – Flanagan had stumbled a few times over one or two of the unfamiliar lines – the song had been captured to everyone’s satisfaction. It was a sound from a bygone era (the final sound, in a way, because Flanagan would die a few months later), and it set the tone for all that was to follow.

Location filming took place between 1 and 6 April. Harold Snoad, David Croft’s production assistant, had selected the old East Anglian market town of Thetford as the regular base. It was a shrewd choice: inside the town itself, the neat rows of grey-brick and flinty houses implied just the right degree of close-knit intimacy. The surrounding area boasted a rich range of vivid natural sights – pine forests stretching out to the north and west, wide open fields, long meandering streams – and man-made contexts – the Army’s Military Training Area was only six miles away at Stanford – in which to frame the fictional world of Walmington-on-Sea. Arthur Lowe travelled down to Thetford by train, Clive Dunn and John Le Mesurier together by car and the remainder of the cast and crew by coach. ‘Everyone knew exactly what they were doing,’ Ian Lavender recalled, ‘except me’:

I didn’t know anything about location shooting. I lived near Olympia in those days, and the journey to TV Centre wasn’t very long, so I just wandered over in the belief that I was going to spend a few hours in Thetford and then come home on the coach. When I got to TV Centre, however, I noticed that everybody had brought their suitcases with them, so I had to invest several shillings for a taxi ride back to pack some clothes! It had never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be coming home at nights – that was how green I was.12

Every external scene for the whole of the first series had to be filmed during that single (unseasonably chilly) week in Norfolk, and, as Lavender remembered, the pace was unrelenting:

It was all a bit of a blur. The only thing I remember of the filming, quite honestly, was when I accidentally came up with Pike’s voice. Most of the filming was mute – because it was going to be mixed in with stock newsreel footage – but one scene, featuring these circus horses going round and round, was done with sound. And all I said was, ‘Have you got the rifles, Mr Mainwaring?’ And this voice came out: ‘Have you got the rifles, Mr Mainwaring?’ Pure shock, I think. And so I more or less stuck with that voice for the next nine years.13

The most surreal moment, said Clive Dunn, occurred when the cast was racing through a few light-hearted scene-setting motions: ‘As we filmed our bits of comedy showing the Home Guard changing road signs to fool the German invaders, a staff car loaded with German NATO officers passed by …, smiling and unaware that we were about to launch into a long comedy series about the Second World War.’14

The evenings were reserved for socialising. ‘There was a good atmosphere right from the very first day,’ Ian Lavender recalled:

I’d been terrified at the start – terrified – but they were all so welcoming. I think I’d already been put through my ‘initiation process’ back in that pub at Chiswick by Arthur. He’d shown me how to smoke a cigarette ‘Arabian style’. He had his own private supply of these cork-tipped Craven ‘A’ cigarettes, and he’d got me to hold one of them like he did, suck it – phew! – and I’d fallen off my stool. That was my first memory of Arthur, socially – making me fall off a bar stool. And then in the hotel at Thetford they were lovely. They’d sort of say things like, ‘Come on, this is your bit as well’, you know, ‘Don’t be afraid of … ’ It wasn’t a matter of taking me under their wing and protecting me, but neither was it a matter of leaving me to sink or swim. They were just very, very, welcoming.15

After Thetford came the rehearsals: at 10.30 on the morning of Monday, 8 April, the cast, Croft and Perry reassembled at St Nicholas Church Hall in Bennett Street, Chiswick, to begin work on the pilot episode, which by this time had been given the title ‘The Man and the Hour’. Some of the actors seemed well-advanced in their characterisations – Arthur Lowe, for example, was quietly confident that both his look (a compressed Clement Attlee) and manner (proud, pompous and pushy) would work rather well, and Ian Lavender (whose prematurely greying hair would be disguised on screen by a combination of colour spray and Brylcream) had decided to give Pike a long Aston Villa scarf (hastily replaced, in the opening credits sequence, by a blue towel because the wardrobe van had left Thetford early), a mildly quavering vocal manner and a childishly inquisitive expression – but one or two, it seemed, were still in need of some advice. Bill Pertwee kept being urged by David Croft to make Hodges even louder and more obnoxious, delivering each line in the music-hall style of ‘on top of a shout’, and Jimmy Perry was and would remain astonished by John Le Mesurier’s unorthodox methods of assimilation: