Полная версия

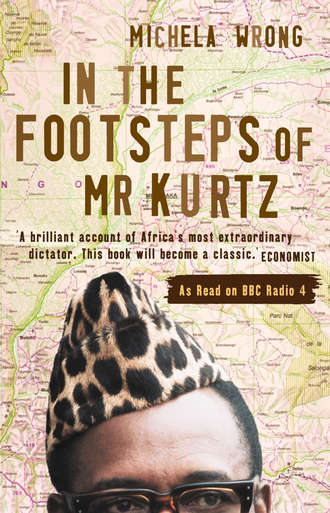

In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in the Congo

His country was young, its sense of self-identity distinctly shaky. He was only the second monarch of an independent Belgian state, whose people had staged a revolution in 1830, turning their backs on centuries of Spanish, Austrian, French and Dutch rule. Despite a distinct lack of enthusiasm on the part of the population, he was determined to use a colony to transform his tiny country, divided by religion and language, into a world power commanding respect.

‘No country has had a great history without colonies,’ Leopold wrote to a collaborator. ‘Look at the history of Venice, of Rome and Ancient Greece. A complete country cannot exist without overseas possessions and activity.’ Scouring the world, he had looked at China, Guatemala, Fiji, Sarawak, the Philippines and Mozambique as possible candidates, but had been stymied at every turn. Then, cantering to the rescue like a moustachioed crusader, had come Henry Morton Stanley.

Stanley was a poor Briton who had emigrated to America, where he had reinvented himself as a war correspondent known for his racy copy and fearlessness under fire. An illegitimate child, he had been abandoned by his mother and sent to the workhouse, circumstances that left him with a deep need to prove himself. Fated to spend his life in a swirl of controversy, Stanley had first seized the public’s imagination by penetrating darkest Africa in 1871 and tracking down David Livingstone, the British missionary who had gone missing five years earlier. Their legendary meeting was one of the great journalistic scoops of all time.

In 1877 he pulled off an even more impressive feat. Proposing to settle the dispute that had festered for years between British explorers John Speke and Richard Burton over the source of the Nile, he set off once more from Zanzibar, tracing the course of the Lualaba river for 1,500 miles. Braving rapids, ambushes, smallpox and starvation, he followed the river, emerging at the Atlantic Ocean after a journey that lasted nearly three years. He had not only established that the Lualaba had no connection with the Nile, which he had shown to spring from Lake Victoria, he had also opened up a huge swathe of central Africa until then known only to the ‘Arab’ merchants (in actual fact Swahili-speaking, Moslem traders from Africa’s east coast) to greedy Western eyes.

In the books Stanley wrote after each extraordinary trip he showed a near-obsession with the dangers posed by perspiration and sodden underwear, which he blamed for malarial chills. But his eccentricities did not prevent him from accurately sizing up the potential of the land he had passed through. Its forests were full of precious woods and ivory-bearing elephants. Its fertile soils supported palm oil, gums and, most significantly, wild rubber, about to come into huge demand with the invention of the pneumatic tyre. Its inhabitants presented a ready market for European goods and, once the rapids were passed, the river offered a huge transport network stretching across central Africa.

Stanley was far from being the first white man to reach this part of central Africa. Late fifteenth-century emissaries from Portugal, looking for the fabled black Christian empire of Prester John, had stumbled on the Kongo kingdom, a Bantu empire spreading across what is today northern Angola, western Congo and edging into Congo-Brazzaville.

A feudal society led by the ManiKongo, this kingdom proved surprisingly open to the arrival of the white man, perhaps encouraged by a spiritual system which identified white, the skin colour of these strange visitors, as sacred. It had welcomed missionaries, embraced Christianity and entered into alliance with the Portuguese. But by the time Stanley was tracing the course of the river, the Kongo kingdom had been in decline for more than two centuries, devastated by endless wars of succession, attacks by hostile tribes and, above all, the flourishing slave trade.

Although it was clearly in his interest to play up the horrors of what he found, for it made the alternative of colonial subjugation seem so much more attractive, Stanley appears to have been genuinely horrified at the damage the ‘Arabs’ had wrought along the river.

‘The slave traders admit that they have only 2300 captives in their fold, yet they have raided through the length and breadth of a country larger than Ireland, bearing fire and spreading carnage with lead and iron,’ he reported in The Congo and the founding of its free state. ‘Both banks of the river show that 118 villages, and forty-three districts have been devastated, out of which is only educed this scant profit of 2300 females and children and about 2000 tusks of ivory … The outcome from the territory with its million of souls is 5000 slaves, obtained at the cruel expense of 33000 lives!’

But his hopes that Britain, his mother country, would seize the opportunities presented were dashed. With London refusing to take the bait, King Leopold II stepped in. One of the last pieces of unclaimed land in a continent being portioned off by France, Portugal, Britain and Germany, Congo fitted his requirements perfectly. Leopold recruited Stanley to return to the Congo, set up a base there and establish a chain of trading stations along the navigable main stretch of the river which would allow the European sovereign to claim the region’s riches.

Stanley found himself in a race against Count Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, a naval officer who was energetically signing up local chiefs on France’s behalf. With the northern shoreline lost to him – hence the eventual establishment of French Congo, with Brazzaville as its capital – Stanley had to content himself with the southern shore of the river, pushing his treaties on hundreds of chieftains. Leopold’s insignia – the gold star on a blue background later, bizarrely, revived by the anti-colonial Laurent Kabila – was raised over village upon village.

Further exploration confirmed Stanley’s first impressions of vast natural riches just waiting to be exploited. ‘We are banqueting on such sights and odours that few would believe could exist,’ he wrote after another trip up river. ‘We are like children ignorantly playing with diamonds.’

Leopold had found his colony. Privately he raved about the potential of ‘this magnificent African cake’. But he was careful to present the situation in less enthusiastic terms to other European powers, wary of signs of expansionism by the Belgian newcomer. The flag flown at the newly established Congo stations ostensibly belonged to the International African Association, a philanthropic organisation Leopold had set up with the stated aim of wiping out the slave trade and spreading civilisation. Leopold encouraged missionaries to set out for the Congo and at the Berlin conference of 1884–5, at which the world powers carved up Africa, he triggered unanimous applause by proposing the Congo as a free trade zone, open to all merchants. His ambitions for the nation, he said, were purely philanthropic. In return, the Congo Free State was recognised as coming under his personal – as opposed to Belgium’s – control.

But, as Marchal’s work makes clear, the situation on the ground was to prove rather less high-minded. Clearing the jungle to build roads, stations and – eventually – a railway linking the hinterland with the sea, Stanley’s ruthless treatment of his native labourers won him the sobriquet ‘Bula Matari’ (Breaker of Rocks).

Unable to read the treaties they had signed, local chiefs discovered they had handed over both their land and a monopoly on trade. King Leopold, noted Stanley, in words that could have been used of Mobutu a century later, had the ‘enormous voracity to swallow a million of square miles with a gullet that will not take in a herring’.

If the signatures were given ‘freely’, Stanley left the clan leaders in no doubt that he had the force with which to pursue his interests. He took great delight in demonstrating the wonders of the Krupp canon, the latest in modern weaponry. ‘Notwithstanding their professions of incredulity as to its power,’ he recounted with satisfaction, ‘it was observed that the chiefs took great care to keep at a respectful distance from the Krupp, and when finally the artillerist, after sighting the piece to 2,000 yards, fired it, and the cannon spasmodically recoiled, their bodies also instantaneously developed a convulsive moment, after which they sat stupidly gazing at one another.’

Later on, the Force Publique, a 15,000–19,000-strong army of West African and Congolese mercenaries, was established to ensure Leopold’s word became law. Weapons and ammunition poured into the region. Just as Mobutu was later to give the nod to a system of organised looting by instructing his soldiers to ‘live off the land’, Leopold expected the Force Publique to provide for itself, pillaging surrounding villages in search of food.

Far from being a free trade zone, the colony’s very raison d’être was to make money for the King. Anxious to attract the foreign capital needed to build railways and bridges, Leopold divided part of the country into concessions held by companies in which he held a 50 per cent stake, with exclusive rights over tracts of forest, ivory, palm oil and mineral wealth. The rest of the country was defined as Crown property, where state agents enjoyed a business monopoly. Independent merchants who ventured into the area in search of ivory found their way physically blocked by Leopold’s officials. When the Arab traders operating in the north and eastern reaches of Congo were eventually driven out after a vicious war against the Force Publique, it was not – whatever the Tervuren museum may claim – because of any outrage over their slaving activities, it was because they threatened Leopold’s commercial interests.

By then, as the boom in the motor industry escalated Western demand for rubber, Leopold’s agents were knowingly mimicking the techniques of the Arab traders that Stanley had decried. Villagers, who had to tap the wild vines growing in the forest for gum, were set cripplingly high production quotas. If they failed to meet the targets, the Force Publique would descend on a village, burn its huts, kill at random and take womenfolk, children or chiefs prisoner until the villagers came to heel. Hostages were used as porters or sold as slaves to rival tribes in exchange for rubber or ivory, and thousands of orphaned children were marched off to Catholic missions to be trained as soldiers for the Force Publique.

Driving the state agents on was a cynical commission system that could double their miserly salaries depending on output and a sliding scale of payment which ensured that those who paid the villagers least for their deliveries of ivory or rubber were rewarded most highly. The lack of compassion seems a little more understandable when one considers the risks inherent in working in the Congo Free State. A staggering one in three state officials desperate enough to try their luck in Africa did not survive their postings, felled by malaria, typhoid or sleeping sickness. With the likelihood of dying in service so high, these young men were none too fastidious about the methods used to ensure output targets were met.

Looking at the mournful black and white photographs taken by appalled missionaries, it is sobering to register that around a century before the amputations carried out by Sierra Leone’s rebel forces sent shudders through the West – reinforcing stereotypes of African barbarism – a white-led, European-commanded force had already perfected the art of human mutilation. Soldiers in the Congo were told to account for every cartridge fired, so they hacked off and smoked the hands, feet and private parts of their victims. Body parts were presented to commanders in baskets as proof the soldiers had done their work well. Hence the photographs that, disseminated by the pioneering British journalist Edmund Morel, a precursor of campaigning human rights organisations such as Amnesty International, eventually shocked the outside world into action.

The chicotte, the gallows, mass executions were all liberally applied in a campaign that often seemed to have extermination of races deemed inferior as an incidental aim. The brutality inevitably triggered uprisings. The ferocity of those revolts was glossed over by colonial officers and subsequently downplayed by academics. But Congolese historian Isidore Ndaywel e Nziem records the words of a Captain Vangele, who was attacked four times by canoes manned by tribesmen from Mobutu’s own equatorial region, as proof the Congolese were no walkover: ‘It was the fiercest battle I have ever experienced in Africa … During that fight that lasted nearly three hours, the Yakoma did not cry out once, there was something terrifying about their silence, their cold determination.’

The Force Publique put down the resistance with ruthless effectiveness. Then, as today, no reliable census data existed in the Congo. But as the Force Publique stole children, destroyed families and spread hitherto unfamiliar diseases in its wake, missionaries began to notice an alarming incidence of depopulation taking place. Marchal hesitates to quantify the phenomenon, but Belgian officials were eventually to estimate that the country’s population had been halved since the founding of the Congo Free State, implying that 10 million people either died or fled the region. Professor Ndaywel puts the figure even higher, at 13 million.

Leopold had done his best to keep Congo’s contacts with the outside world to a minimum, trying to ensure a good press by discouraging visitors and systematically bribing politicians and journalists in Europe. But by the first years of the twentieth century, works such as Heart of Darkness were echoing what Roger Casement, a British diplomat, was to officially establish in a 1903 report commissioned by the European powers. Detailing cases of natives being forced to drink white men’s urine, having their bound hands beaten till they dropped off, being eaten by maggots while still alive and fed to cannibal tribes on death, Casement destroyed any remaining illusions. What had been laughably dubbed the Congo Free State was an exploitative system premised on forced labour, terror and repression.

Under pressure from foreign allies and his own parliament, the ailing Leopold agreed in 1908, after long negotiations, to hand over Congo to the Belgian state, instead of bequeathing it to his country on his death as he had originally planned. He died a little more than a year later, having never once set foot in the colony his policies had so devastated.

But he had achieved his aim. Congo’s massive contribution to Belgium’s development is still on show in the capital, if only you know where to direct your gaze. Leopold was a king who wanted to leave his mark on the city of Brussels, and brand it he did, thanks to this independent monetary source he could tap at will.

For visitors interested in the history of Brussels, several companies today offer themed coach trips around the city. A favourite is the Art Nouveau tour, which traces the rise and fall of the design movement that blossomed on the cobbled streets of the hilly city as nowhere else, and the high moment of the tour is undoubtedly the apricot-coloured Hotel Van Eetvelde on Avenue Palmerston, around the corner from the Jamaican embassy and a stone’s throw from the plate-glass horrors of Euroland.

Here architect Victor Horta, guiding light of the Art Nouveau movement, was given free reign by Edmond Van Eetvelde, a wealthy diplomat who wanted a fitting venue in which he and his wife could receive business guests. ‘I presented him with the most daring plan I had ever, until that point, drawn up,’ recalled Horta. Taking advantage of the blank cheque issued him, he produced a building so lavishly decorated, so consistent in its artistic vision, the overall effect is almost nauseating.

From the octagonal drawing hall to the mosaic floors, from the delicate tendrils of the wrought-iron banisters to the motif on the coloured glass roof, the Hotel Van Eetvelde is pure Horta. It is also pure Congo. The hardwoods that lined the ceilings, the marble on the floors, the onyx for the walls and the copper edging each step of the curving staircase all came from the colony. What did not come directly from the colony was paid for with its proceeds, for Van Eetvelde was more than just a well-connected diplomat – he was secretary-general to the Congo. One of Leopold’s most trusted collaborators, he was rewarded in 1897 for his loyal services with a baronetcy, before eventually being sidelined by a king whose judgement he had dared to question.

The Hotel Van Eetvelde is only one of the many architectural extravagances Congo’s exploited labourers made possible. The Cinquantenaire arch, the grandiose baroque gateway to nowhere, built to celebrate Belgium’s golden jubilee; the endless improvements to the Royal Palace at Laeken, including the vast royal greenhouses, Chinese pavilion and Japanese tower; the museum at Tervuren; Ostend’s golf course and sea-side arcade and a host of other works were all provided by the Congo. But there was more, much more, and not all of it quite so obvious to public eyes: presents for Leopold’s demanding young mistress; a special landing stage for the yacht he, like Mobutu later, would use as a place to hide away from an increasingly hostile public, spending sometimes months aboard; Parisian châteaux; estates in the south of France and a fabulous villa in Cap Ferrat, not far from where Mobutu would buy a mansion.

The two men shared more than just a knack for large-scale extortion and lavish spending tastes. Indeed, in money matters, the present echoes the past to an almost uncanny extent. Both leaders were to prove remarkably adept at squeezing loans out of gullible creditors and luring private investors with a taste for adventure to Africa. Both covered their tracks with a system of fraudulent book-keeping. Both indulged in similar stratagems in an attempt to cheat the taxman after their deaths and both, having feathered their own nests, left Congo with a heavy burden of debts to be settled after they quit the scene.

In contrast to most African colonies, the Congo Free State was a money-maker almost from birth, thanks to Leopold’s eye on the bottom line. But the king did his best to conceal that fact, succeeding so well in obscuring the true situation that a British journal of the day erroneously reported: ‘It is by no means certain that Belgium will not tire of the Congo. Already this vast area has been a huge disappointment to the mother country. Its resources and population have not proved in any way equal to Mr Stanley’s florid accounts.’

Pleading near bankruptcy, Leopold managed to win two major loans worth a total of 32 million francs from the Belgian state in 1890 and 1895, paid out in yearly instalments. But while the faithful Van Eetvelde was drawing up fictitious budgets underestimating revenues, thereby ensuring the government maintained subsidies for a colony the public had never wanted in the first place, profitability was sharply on the rise. By 1901 ivory exports stood at 289,900 kilograms and rubber production had gone from 350 to 6,000 tonnes a year. Congo was providing more than a tenth of world production of this key raw material, bringing in somewhere between 40 and 50 million francs a year. The king also made money by issuing more than 100 million francs worth of Congo bonds, effectively printing money with the same liberality as Kinshasa’s central bank was later to show when it came to issuing notes.

When Leopold was finally forced to hand the colony over to Belgium, he did so at a high price, wheedling 50 million francs from the government in recognition of his endeavours. The Belgian government, which had always been assured it would never be sucked into the king’s African adventures, found itself agreeing to assume Congo’s 110 million francs in debts – much of that sum comprising the bonds Leopold had issued – and contribute nearly half as much again to completing the building projects the king had drawn up in Belgium.

No one will ever know for certain how much profit Leopold himself drew from the Congo Free State. He adopted the methods beloved of many a modern-day African strongman when it came to trying to hide the extent of the wealth he had accumulated. Real estate was bought through aides, money secretly funnelled into a foundation dedicated to building projects, and shadowy holding companies set up in Belgium, France and Germany. Before handing over responsibility for his African colony, Leopold was careful to burn much of the Congo documentation, protecting himself as far as he could from the scrutiny of future scholars. Belgian investigators only succeeded in unravelling the complex network of his investments in 1923.

By then the world’s attention had moved elsewhere, satisfied that the human rights abuses in Congo had halted with the Belgian’s government takeover. Not so, insisted Marchal, who aimed to challenge this comfortable myth in the book he was currently writing about the system of forced labour imposed by Belgium’s Union Minière, the company that continued running the mines in Congo’s southern Katanga region well after independence. ‘When I finished writing about Leopold, I thought it would be over for me, because I believed all those professors who said when Belgium took over everything was wonderful. But I’ve seen that things remained the same, the system was nearly as brutal, it just became more hypocritical. I now have material for another three or four books.’

Marchal’s own memories might have suggested as much. The system of forced cultivation in the cotton industry he enforced as a young man lasted until independence in 1960; use of the chicotte, that mainstay of colonial rule, was outlawed only ten months before Belgium pulled out. The officials who had worked under Leopold had a new master but largely remained in situ. Reforms were applied only slowly. It was only after the Second World War, Marchal now believed, that the Belgian Congo became ‘a colony like the others’.

Even then, Belgium hardly distinguished itself. True, it had established an infrastructure whose modernity was marvelled at by European visitors. To take just one example, Congo at independence had more hospital beds than all other black African countries combined. But daily life resembled that adopted in South Africa under apartheid rule.

The capital was divided into the indigenous quarters and the Western zone, where blacks were not allowed after a certain time and would be refused drinks in hotels and restaurants which were reserved for whites only. Referred to as ‘macaques’ (monkeys) – a term still contemptuously spat out by heavy-drinking expatriates in Kinshasa – Congolese were set the qualification of ‘évolué’ as a target. This was a certificate indicating they were Africans who had ‘evolved’ far enough to adopt European attitudes and behaviour. But it was not enough to allow them to accede to positions of responsibility and power.

Certain experiences are calculated to stick in the gullet. Long, long after independence, one of the MPR’s leading lights would sometimes recall the time when a Belgian colonial official came round to verify the cleanliness of his parents’ toilet before issuing the permit that allowed them to buy wine. In schools, children from such ‘evolved’ Congolese families would be taken aside each week to be checked for fleas, an indignity spared their white classmates.

Acting on the principle of ‘pas d’élites, pas d’ennemis’, – the theory that an educated African middle class would prove dangerously subversive – the Belgians did virtually nothing to pave the way for independence, expected in 1955 to be decades off. When the government was forced to hand over in the face of growing protests in 1960, only seventeen Congolese youths had received a university education. The withdrawal was one of the most abrupt in African history.

Why did this small European nation prove such an appalling colonial power? One gets the impression that Leopold was rushing so desperately to catch up with his foreign allies, self-restraint and principles were simply jettisoned along the way. Maybe a country in its infancy did not possess the self-confidence necessary to show magnanimity when imposing nationhood on others. As tribally divided as the nations hacked arbitrarily from Africa’s land mass by the colonisers, Belgium barely had a sense of itself, let alone itself in the novel role of master.