Полная версия

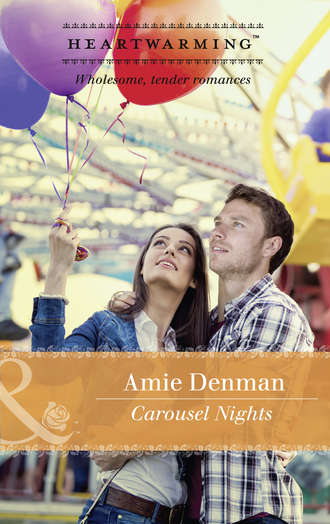

Carousel Nights

“I don’t think I ever got to tell you how sorry I was about your father’s death,” Mel said.

June met his eyes. “You did. You were at his funeral.”

“The whole town of Bayside and anyone who ever worked at Starlight Point was at his funeral,” Mel said.

“I remember talking to you.” She smiled and her whole face softened. “You brought me a tissue and a glass of iced water.”

Although the entire Hamilton family was shocked at Ford’s death, June seemed to take it the hardest. Maybe that’s because she felt guilty about not being around the past few years. Was that why she decided to come home this summer?

“Least I could do,” he said.

“And you’ve been there for Jack,” she said, standing and moving closer. “When he took over last spring, he needed a good friend.”

“We all do.”

June crossed her arms and leaned back on a porch post. She stared at her feet for fifteen seconds while Mel counted silently. He recognized the grubby work boots she’d had for years. She’d worn them as she helped around the park in the off-season until she went away for college. He remembered every tool she’d ever handed him and each ride she’d accepted in his cart. The owner’s daughter and his best friend’s sister who’d always been around.

“Can you tell me why the main electric switch won’t turn on in this old theater?” June asked, adopting a neutral, businesslike tone. “I have to finish cleaning in here and I need to keep working when it gets dark or I’ll never get it all done.”

Mel had never doubted June’s dancing ability, but he wished she wasn’t using it to sashay a wide circle around him. There was no question it was better that way. Better to pretend that summer seven years ago and that kiss had never happened.

He picked up his clipboard. “Don’t think that’s on my orders for the day,” he said, trying to keep his tone light. “I’m supposed to run electrical diagnostics on the Sea Devil, fix the organ’s circuit board on the Midway Carousel, and call the state inspectors about the ride license for the Skyway cars. Boss won’t like it if I get diverted.”

June snorted. “You are the boss.”

Mel smiled. “I love hearing you say that. How about once more?”

“Very funny.”

“It is funny. Because you, Jack and Evie are in charge of this place. I just work here.”

He swung one leg into his cart, turning his back on June.

“Hey,” she said.

Mel tensed, wriggling his shoulders in his blue work shirt, the tag grating the sensitive skin on the back of his neck. He turned toward June and fought a grin. She looked hopeful and bossy at the same time. Close to the six-foot mark with long, slim arms and legs, she reminded him of Jack. Her green eyes flecked with brown and her full lips made Mel remember she’d briefly been his girlfriend. Until she’d left for college and left him cold.

“I can spare a half hour,” he said. “But you have to help. The wiring in there hasn’t been updated during my lifetime, and the conduit runs up high over the stage.” He strode over and stopped in front of June, eye level with her on the elevated porch. “It’s going to be a real pain in the neck,” he said.

June laughed, stepped back and shoved through the swinging saloon doors.

* * *

IF SHE WANTED to revisit a time when her insides didn’t flip whenever Mel Preston came into view, she’d have to go back about a decade. The first time she’d seen him was at her older brother’s seventh birthday party. Even then, his sandy hair and blue eyes combined with a giant smile had set him miles above Jack’s other friends. When high school rolled around, she’d started to realize just how much she liked him. Now, at six foot three, Mel was easily head and broad shoulders over other men. Except Jack. June’s older brother and Mel had competed for vertical supremacy throughout high school until Jack finally edged Mel out by one inch during a late-teen growth spurt.

Gradually, over the last decade, their easy relationship had heated, tempered, flared, cooled and simmered. But never jelled. It didn’t have a chance to because June couldn’t give up her dream to tap her toes on Broadway. The two live theaters at Starlight Point with their creaking floors and seats were not enough for her then or now.

How ironic that she was standing in one of those theaters and trying to make it sparkle. Temporary, she reminded herself.

She tilted her head to see Mel balanced on a ladder ten feet over the stage. Only his worn work boots were visible from her angle. A screwdriver clattered to the floor, almost clobbering her on its way down.

“Sorry about that,” Mel said. “Can you toss it back up here?”

“I’m a bad throw,” she said, picking it up. The handle still held Mel’s heat.

He chuckled. “I know.”

“Hey,” she said. “I was only ten and you guys were twelve. Big difference. And I didn’t want to play baseball anyway but you were short a player.”

“That was my first time replacing a pane of glass,” Mel said. “I did okay and your parents probably never would’ve known if Evie hadn’t told on us.”

“Too young to know better,” June said. “She was only six or seven.”

June tossed the screwdriver up but missed by several feet, causing Mel to overreach and almost fall off the ladder.

“I better come get it before someone loses an eye,” Mel said.

He backed down the ladder while June crossed the stage to retrieve the fallen tool. Her back to him, she said, “Your son’s about six, isn’t he?”

“He’ll turn six this summer. Starts first grade in the fall.”

She turned to face him as he stepped off the bottom rung, a flicker of silence between them.

Mel jerked his head toward the upper catwalk without taking his eyes off June. “Think that old catwalk for the lighting will hold my weight?” he asked. “I don’t know if it’s been used in years.”

“I hope so. My shows include lots of lighting. Maybe some special effects.”

“In the Wonderful West? Seems out of place,” Mel commented.

June rolled her eyes. “What you know about theater would fit in your back pocket.”

“Maybe,” he said, taking the screwdriver from her outstretched palm, “but that’s where this goes. Lucky for you, I know about electricity.”

June watched him climb one rung at a time. When he reached the junction box ten feet up, he put a small flashlight between his teeth. Although full daylight outside, the theater was dim.

“I’ve gotta follow this line,” Mel said. He climbed another five rungs and eased onto the narrow metal catwalk that hugged the theater on three sides. Ancient spotlights were mounted beneath it and cables snaked over and under it.

“Seems solid,” Mel said. “I’m going down to the junction box in the corner. I have to see where we have spark and where we don’t.”

Good idea, June thought, following his progress as he crawled along the back wall. She held her breath when he slid across a gap between missing supports. When he reached the corner, the flashlight between his teeth threw patterns of light on the wall as he banged at something metallic.

“Any luck?” June called.

“Just...” The flashlight clanked onto the steel catwalk, rolled off and crashed onto the floor near June. The light went dark.

“Shouldn’t have opened my mouth,” Mel said from the darkness above her.

“My fault,” June said. “I asked you a question.”

“You can make it up to me by digging through the toolbox on my cart and finding me another flashlight.”

“Be right back.”

June headed for the daylight streaming through the front windows. Mel’s cart had two toolboxes and she had to dig through both before finding a large industrial-looking flashlight.

Inside, Mel’s long legs hung over the side of the catwalk fifteen feet up. He swung his feet like a kid waiting for his third-grade girlfriend on the playground.

“Can I convince you to bring that up here?” Mel asked.

“I could throw it.”

“I haven’t got a death wish. Just come up the ladder and I’ll crawl along the catwalk and meet you at the top.”

He didn’t wait for an answer. She knew he wouldn’t. June had worked at Starlight Point until she was eighteen. During the off-season, she’d tromped around handing tools to maintenance men after school, climbing the emergency steps on coasters and taking any challenge. When she was old enough to officially work, she’d sold popcorn until she finally convinced her parents to let her dance on stage. Although her parents owned the amusement park, they made their children work regular summer jobs. It was a great way to see Starlight Point from the inside out, and all three of them had earned reputations as hard workers.

Mel had every reason to think she’d scamper up the ladder, flashlight in hand, like she would have done in the past.

But the shining aluminum faced her like a demon.

Her heart rate accelerated as she placed one foot on the bottom rung and pulled herself up with her free hand. One rung down, at least fifteen more to go. Maybe she could do this. Jumper’s knee. That’s what her doctor had called it. If she stretched, did her exercises, and avoided stairs and high-impact jumps, it would get better. She’d been taking it easy, keeping her movements small and not telling a soul. She felt stronger, ready to take on these theaters and get on with her life.

She sucked in a breath and steeled herself for another vertical step.

Pain streaked through her right knee when she put her foot on the next rung and tried to pull herself up. Agonizing pain. Ladders were not on her therapy plan. A wave of nausea hit her and sweat chilled the back of her neck. She dropped the flashlight and grabbed both sides of the ladder. She stepped backward to the floor, fumbling for the light, afraid to look up. Back on both feet, the pain subsided and she took a deep breath.

“What are you doing?” Mel asked.

Trying to pretend everything is just fine. “Picking up the flashlight,” she said tersely. “What does it look like?”

“At this rate, it’ll be dark before I even get started. That’s an expensive light, so be careful with it.”

“Sorry,” she said, eyeing the ladder and trying to think of a graceful way out. Her heartbeat pulsed through her neck and hammered in her ears. She risked a glance up. Mel lay full length on the catwalk, his chin propped in his hands. Waiting for her.

But that was a mountain she was not climbing today.

She parked the light at the bottom of the ladder. “If it’s so precious, you better come get it yourself,” she said. “I’m going back to work in the prop storage room.”

She walked slowly and carefully away, willing herself not to show a trace of weakness. Would Mel let her off the hook? The catwalk overhead groaned and the ladder behind her creaked as Mel started down it.

“Don’t know when you became such a princess that you can’t help a guy out,” he said.

June counted to thirty, numbering her steady steps to the storage room door. She closed it, sat on a box and elevated her leg on a dusty plastic hitching post. She was still sitting there staring at years of props in the gray light from the solitary window when the overhead fluorescent lights buzzed on. She waited, listening, until Mel’s cart started up and drove away. Rubbing her knee, June tried to quell the panic in her chest. If she couldn’t dance, she couldn’t go back to Broadway and the roles she had already sacrificed so much for.

CHAPTER THREE

EVIE SAT AT Jack’s desk, staring at his computer through her green-rimmed glasses. Three years younger than June, Evie was generally sweet, except in her ruthless devotion to accurate accounts. And her attitude toward the architect June had hired to fancy up the two live-show venues.

“The money is one thing. But I don’t see why we should pay his hourly rate when we already have our own planners,” Evie said. “And how much do you think we can really get done on the facades when the park opens in a week? It’s nuts.”

Jack, who was standing by the window, raised one eyebrow at June. His look said you’re on your own with this argument.

June wasn’t asking for the moon and stars. She just wanted the theaters to look like they hadn’t been designed by the same person who’d imagined the cheeseburger stand. Something a little more modern—even a new paint scheme and lightbulbs would be better than nothing.

“Fresh blood,” June said. “Our planning guys will just come up with the same old same old.”

“So?” Evie asked. “Same old ensures continuity. People like the old-fashioned aura. Even if you don’t.”

“News flash,” June said. “Change is good.”

June crossed her arms and leaned against the large window beside Jack. He’d finally moved into their father’s office over the winter. Last summer, he’d kept the smaller office next door out of a combination of shock, grief and respect. Moving into this office—rich with their father’s history, his big wooden desk, awards and mementos from years in the business—was a sign Jack was growing into the job of CEO.

“I refuse to be the grown-up here, if that’s what you’re thinking,” Jack said. “Just because I’m the tallest and smartest of the three of us.”

Evie breathed loudly through her nose and stared down her older siblings. When had she gotten so opinionated? Evie had always been the nice, sweet one. Hadn’t she? June had been away for seven years, and in that time Evie had gone from fifteen to twenty-two. Practically a lifetime.

“Fifteen hundred bucks so far and all I’ve gotten out of him is an argument,” Evie said.

“You argue with people?” June asked.

“I’m doing it right now.”

“That’s different,” June said. “We’re related. And what the heck is wrong with doing something new around here? You opened the Sea Devil last year. A multimillion-dollar roller coaster is a pretty big deal compared to what I’m suggesting.”

Although it was by choice, June felt like a third wheel when she had meetings with Jack and Evie about Starlight Point and its future. The small profits last year had been split three ways. This year’s profit would be split as well, even though it’d certainly still be modest as they worked to convince the bankers to extend the loan.

June wanted to earn her share, small though it was. And theater was the best way she knew how to do that. Better shows could mean more ticket sales. They might bring local pass holders across the Point Bridge a few more times each summer to see the shows, and locals spend money on popcorn, elephant ears and soda.

“The Sea Devil was Dad’s idea,” Jack said. “He started it, he just didn’t get to finish it.”

“Are you saying you wouldn’t add new rides in the future?” June asked.

Jack exhaled slowly, staring out the second-floor window at the front section of the midway. “I’m saying I wouldn’t go that big, especially if it practically bankrupted us. Not anytime soon.”

“Our plan for this year is good,” Evie said. “Small improvements that guests will notice. New paint, a few new facades on buildings—”

“Like both theaters,” June said.

Evie went on as if her sister weren’t even there. “Restroom upgrades, new safety belts in the children’s rides, new signs on the Point Bridge. But we’re not breaking the bank.”

“Unless the bank breaks us,” June said.

Jack waved at someone outside and then turned back to his sisters. “If we made it through last year, we’ll make it through this year. The bankers liked what they saw last summer even though we had very little time to do anything. We have a solid plan. And one of our owners is now a CPA with more money sense than the other two of us put together.”

“Hope it helps,” Evie said.

“Credibility,” Jack said, “helps make up for the fact another one of the owners is a Broadway dancer who never sticks around.”

June narrowed her eyes and threw a pencil at him. The elevator outside Jack’s office dinged.

“Mom,” Jack whispered. “And she’s got Betty with her. I just saw them outside.”

Virginia Hamilton zipped into the room. She pulled a red wagon behind her and parked it by Jack’s desk. The brown, black and white dog snoozing on a blanket in the wagon opened one eye, yawned and went back to sleep.

Evie rolled over in Jack’s chair and stroked the dog’s ears. “Betty smells good today,” she said, smiling at her mother.

“Just picked her up from the groomer. She rolled in something dead on the beach yesterday,” Virginia said. “How’s it going here in the war room with one week before the big opening?”

Jack groaned loudly. Evie rolled back to the desk. And June looked out the window, thinking about big openings she’d been part of before. Opening day at the park every year through her eighteenth birthday. Opening night of four major Broadway productions. She was getting to be a pro at pulling a show together.

The elevator dinged in the silence and Mel ambled in.

He stopped. His eyes met June’s and held for a heartbeat until he shifted to the oldest member of the family.

“Sorry,” he said. “Don’t mean to interrupt. I just came by to see if Jack wanted to get some lunch. I need a break from trying to figure out how water got into the circuit boards of the Silver Streak over the winter.”

June hadn’t seen Mel since he’d turned on her lights at the Starlight Saloon. She’d heard through Jack that Mel was rewiring the entire theater before he’d allow even one extension cord to be plugged in, so she’d avoided the Saloon for a week, focusing on costume and prop designs instead.

“Gus is bringing lunch,” Jack said. “She’s coming over anyway to get her three bakeries ready to open.”

“I hear she’s working up some new creations for this summer, themed pies and turnovers,” Mel said, wiping a fake tear and using a tragic voice, “I love your wife.”

Jack punched Mel’s shoulder. “There’s probably enough lunch for you, but no way am I sharing dessert.”

“I can live with those rules,” Mel said. He dropped to one knee and made kissing sounds to Betty, who hopped out of the wagon, threw herself at him with embarrassing abandon and rolled over for a belly rub.

Virginia cleared her throat. “While we wait, I thought we could talk about my STRIPE program this year.”

June turned back to the window, staring outside. Every year, Virginia muscled someone into running the Summer Training and Improvement Plan for Employees. Every employee had to participate and learn a specific skill such as conversational French, water rescue, ballroom dancing, knitting. In the past, the program had been mandatory. Last summer, it had become voluntary. But it was still an onerous task for whoever Virginia chose to be the STRIPE sergeant.

“Any ideas?” Virginia asked, enthusiastically. “What should the STRIPE topic be this year?”

“I’m off the hook,” Gus said, coming through the door with a cardboard box filled with paper bags and drinks. “I taught hundreds of people to decorate a birthday cake last summer. I’m still recovering.”

“And you were wonderful,” Virginia said. She cleared a space on Jack’s desk so her daughter-in-law could set the box down.

Jack approached the food, eyeing the bags but avoiding direct eye contact with his mother. June smiled at his pathetic attempt. If he thought cowering would save him, he was in for a surprise.

“How about kayaking, Jack?” Virginia asked. “The lake is one of our best assets, and you’re such a good rower. You’d be great.”

“Sorry, Mom, too busy. And I don’t know where we’d get dozens of practice kayaks.”

“Don’t we rent those on the hotel beach?” June asked. “I thought we had thirty or forty kayaks.”

When their mother turned her back, Jack stuck his tongue out at June.

“Evie,” Virginia said, turning to her youngest daughter, “no one can doubt the importance of managing money. You could teach practical bookkeeping. How to balance a checkbook. Perhaps the wisdom of investing at a young age.” Virginia’s face lit up. “Stock tips!” she proclaimed.

Evie took off her glasses and cleaned them meticulously until her mother moved on to her next target.

“June,” Virginia said, approaching June’s hiding spot by the window. Great, she thinks I’m going to teach them all to dance. Maybe I should tell her about my bum knee instead of keeping it a secret. I could use a great excuse for getting out of the STRIPE.

“How about teaching piano lessons? Wouldn’t it be wonderful if everyone could play something nice like Für Elise or Happy Birthday on the piano?”

June blew out a sigh. Teaching two thousand summer employees to read music and play the piano with both hands would be worse than teaching the tango. “You can’t play the piano, Mom, and you’re perfectly fine.”

“I’d be better if someone would teach me to play.”

“Sorry, no time,” June said, eyebrows raised in innocence. “Choreography, costumes, blocking... The theaters are a huge task. Huge. Plus, I may have to take a short-notice trip to New York for auditions at some point. Can’t guarantee I’ll be here on the class days. You’d have to hire a substitute teacher. Could get pricey.”

“It might give you a purpose,” Virginia insisted. “Make you feel like you’re part of the team.”

June felt her cheeks heat. She wondered when the guilt trip would start. Jack and Evie were devoting their lives to the family business. Why wasn’t she?

She could explain in one sentence. She didn’t want to. She’d never made any promises and she had a right to her own career—a career she hoped would soon step beyond dancing into lead singing and acting roles. She had no plans to give that up.

“I don’t need a purpose. I have my own life. I’ve already given up my summer to be here. If that’s not enough for you, I don’t know what you want.”

June saw Evie’s face flush, probably mirroring her own. Augusta focused on handing out lunches. Jack dug into a sandwich.

Only Mel appeared willing to get in the middle of the family volley.

“Simple electricity,” he said.

Everyone turned to stare at him. What is he doing?

“Electrical circuits,” he said. “Basic wiring.”

More staring.

He accepted a sandwich and a drink from Virginia, smiling and asking, “Don’t you think it would be a good idea for people to learn something about voltage and current? Maybe wire a switch?”

Virginia swished her lips to the side. “You mean for a STRIPE topic?”

“Uh-huh,” Mel said.

“Don’t most people hire an electrician?” Jack asked. “Like you?”

“For big jobs, yes,” Mel said. “Same reason they go to a bakery for big or fancy cakes.” He nodded at Augusta who gave him a two-eyebrows-raised look of skepticism.

“But you can make birthday cakes at home,” Mel continued, “and you can do a lot of wiring on your own, too.”

Why was Mel arguing to be in charge of the STRIPE when he’d probably spent the last decade dodging the event? He had to be out of his mind. Everyone in the office was looking at him as if he’d just announced an elegant tea party in the maintenance garage.

“I don’t know,” Virginia said. “Electricity can be dangerous.”

Evie laughed and rolled her eyes at her mother. “Water-skiing was dangerous, Mom. The water rescue thing two summers ago was dangerous. Even the conversational French got pretty dicey when some of our locals tried it on the international workers we hired that year.”

“That was not my fault,” Virginia said. “French is a very romantic language.”

“Sounds like voltage is the safe choice this summer,” Mel said. “Can’t cause an international incident with that, and I’ll make sure no one gets electrocuted.”

Virginia sipped her drink and stared at Mel. “Do you think you could teach hundreds of summer employees about electricity?”

“I’d need plenty of help,” Mel said. “Some of the other maintenance guys are really good and all of them know at least something about electricity. But I still need volunteers. Guys I can get, but I’d like females, too. It’s good evidence there’s no gender bias in wiring a circuit.” Mel grinned, catching June’s eye. “Women can handle sparks just as well as men can.”