Полная версия

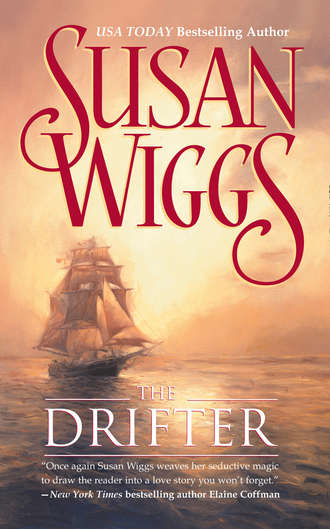

The Drifter

A chill rose up and spread through Leah. Her suspicions, the ones she had been beating down since first laying eyes on Carrie Underhill, came back stronger. She moved the coverlet aside.

Carrie clutched at the quilt. “Jackson!”

“She doesn’t like being uncovered,” he said. “Likes being wrapped up tight.”

“I need to examine her,” Leah snapped. Then, collecting herself, she turned back to Carrie. “I’ll be quick,” she promised. As gently as she could, she palpated Carrie’s abdomen through the fabric of a clean flannel nightgown.

An outlaw who did laundry…

What was a ruthless man like Jackson T. Underhill doing with this fey and delicate creature?

The scent of laundry mingled with something sharper, an odor that was rusty and unmistakable.

She looks to be about three months along…

Leah’s hand touched the abdomen low. Carrie screamed. Her legs came up to reveal an angry smear of fresh blood on the sheets.

“Jesus!” Jackson grabbed Leah’s arm and yanked her back. “You’re hurting her.”

Leah drew him away from the bed and into the recess of a dormer window. Lowering her voice so Carrie wouldn’t hear, Leah leaned toward Jackson. “When did the bleeding start?” she demanded. “Why didn’t you call me?”

“I didn’t know she was bleeding.” Fear edged his words. “I thought she was doing better, just sleeping.”

“She didn’t tell you?”

“No. She—I don’t think she knew, either.”

“I’m afraid she’s miscarrying,” Leah said.

“What’s that mean?” he demanded, clutching her arm, holding tight.

Leah wrenched her arm away. “She’s losing the baby.”

“So fix it.”

The chill inside Leah froze into a ball of fear. “It’s all I can do to save the mother.”

“So save her. Do it now,” he said, raising his voice above Carrie’s high, thin keening.

“I don’t think you understand, Mr. Underhill. It’s not that simple. She might need surgery.”

“Surgery. You mean an operation.”

“I have to stop the bleeding.”

His face paled. “Surgery,” he repeated.

“Yes, if the bleeding doesn’t stop.”

“No.”

She could see the shape of his mouth, but she made him say it again. “I didn’t hear you, Mr. Underhill.”

“No. You aren’t going to hurt her anymore.”

Furious, she tugged on his hand, leading him out into the corridor.

“You aren’t operating on Carrie,” he repeated, his voice low and threatening. “She’s not some critter for you to experiment on.”

“How dare you,” she shot back. “I’m a healer, Mr. Underhill. Not a butcher. Believe me, I would give anything not to have to do anything invasive to your wife, and I will try to stanch the flow as best I can. But if we ignore the problem, the bleeding will continue. Toxins will spread through her body, and she’ll die. A slow, painful death.”

He pressed himself against the wall of the corridor, leaning his head back and closing his eyes. “Damn it. God damn it all to hell.”

“Mr. Underhill, this isn’t helping your wife. You have to make the decision.” A thin wail of pain drifted from inside the room. “You have to make it now.”

He moved so fast that Leah didn’t even realize it until he was clutching her by the shoulders, shoving her up against the wall. The desperate strength in his fingers bit into her upper arms. He put his face very close to hers. She caught his scent of bay rum and leather.

“Look, lady doctor. You’re telling me she could bleed to death?”

“That’s correct.” She tried to glare him into releasing her, but he only held her tighter. She moistened her lips, trying not to let the fatigue of a long day bother her. “An infection could take hold, and she’s too weak to battle an infection.”

“Then you fix her.” He spoke in a low, icy undertone. “You do it now. You stop the bleeding and you make her well. Or I swear to God I’ll kill you.”

Leah and her father had argued long and loud about outfitting an operating theater in the surgery. Edward Mundy claimed to scorn the fancy, big-city ways of modern medicine. In truth, what he scorned was spending money on anything but himself. Leah rarely won an argument with her father, but when it came to her profession, she found strength in her passion for healing.

In the end, she had prevailed and was rewarded with a tiny but innovative theater adjacent to the main suite. It was nothing so grand as the busy hospital theaters where she had learned her brutal craft in Denver and Omaha, but it was an impressive facility for a small island town.

She religiously followed the antiseptic methods of Dr. Lister of Great Britain. Lister had proven beyond a doubt that sterilizing the operating theater reduced the risk of infection. Penny Lake had written to say that all the surgeons of Johns Hopkins were using rubber gloves during surgery. Leah willingly embraced the technique.

Her assistant, Sophie Whitebear, had returned from Port Townsend. With quiet competence, she sprayed the chamber with carbolic acid solution until a fine mist hung in the air. Everything—their gowns, their hair, their sleeping patient, the instruments, the walls and the floors—grew damp and acrid-smelling.

When all was in readiness—the light in place, the patient draped, the dressings and instruments at hand—Leah closed her eyes and said a quick prayer. She had done this many times, had probed dozens of bodies in search of bullets or gallstones or bleeding tumors, but each time, she was overwhelmed with the enormity of invading the sanctity of the human body.

Dear God, please guide my hand in this. Please….

Holding her breath and her nerves perfectly steady, she began.

Three

There wasn’t a goddamned thing he could do.

Like a caged beast, Jackson prowled the surgery. His gaze kept cutting to the enameled white door. Beyond that door, in a room lit so brightly his eyes hurt, Carrie lay bleeding. He might have looked his last at her as they brought her into the strange, foul-smelling chamber. She might never awaken again. He might never again see the color of her eyes, hear the sound of her voice, feel her hand grasping his.

Bitter guilt seared his throat. From the time they were children in the orphanage, he had promised Carrie he’d look out for her. But the deadly bleeding was a shadow enemy. He couldn’t beat it in a fistfight or run away from it. He had to put all his faith in an ill-tempered lady doctor who clearly had no respect for him and not a whole lot of compassion for Carrie.

Fear had become a familiar companion to Jackson. His life had been, for the most part, a series of horrifying incidents, from the moment his mother had abandoned him on a stoop in Chicago to the moment he’d fled Texas with a man’s blood on his hands. But this fear was sharper and colder than anything he’d ever felt.

He hated being in this position. Helpless. Without choices. Powerless to do anything. God, how long was this thing going to take? he wondered.

Grim silence shrouded the surgery. The lady doctor and her assistant weren’t saying a word. Carrie was under ether, blessedly senseless, thank God. The only sound came from a wood-cased mantel clock. The incessant ticking pounded out a hammer rhythm to Jackson’s anxiety, seized his mind and wouldn’t let go.

Gritting his teeth, he forced himself to stop pacing. The outer office was snug and painfully neat with apothecary jars lining one wall and shelf after shelf of textbooks. Above a woodstove hung a picture of a misty green-and-gold island with palm trees nodding over a calm bay. For a moment, Jackson stared at it.

Paradise. He could almost smell the perfume of exotic flowers, hear the call of colorful birds. He wondered if such a place actually existed.

Hungry for a distraction, he moved into the tiny inner office. Ah. Here, at least, was a bit of evidence that Dr. Leah Mundy actually had a life. That she was not some clockwork female sawbones who snapped out orders and intimidated people into getting better. Several diplomas lined one wall. Jackson had never actually seen one up close before, and he was fascinated by the scrolling script that spelled out high honors and important degrees.

She had attended institutions that sounded both imposing and exotic—Great Western, Beauchamps Elysées, Loxtercamp Hospital. She had read books such as Delafield & Pudden’s Pathology and Osteology of the Mammalia. Tucked between the medical tomes was one slim volume. He had to tilt his head to read the title: Ships that Pass in the Night: A Tragic Love Story by Beatrice Harraden.

An educated woman. Jackson was fairly certain he had never met one before.

He picked up a framed tintype of Leah and a bewhiskered gentleman. Jackson squinted at the image. A father. He had no idea what it felt like to have one; he’d been told he was sired by a Nordic lumberjack at a Chicago brothel.

He’d never allowed himself to care about not having a father. But he could tell from the expression on Leah Mundy’s face in the picture that she cared very much. Her hand gripped his arm. Her other hand held a rolled certificate—one of the diplomas on the wall? The bearded man exuded a chilly hauteur while Leah beamed with the eagerness of a pup.

Something had happened since then to beat her down. She was smart as a seasoned cardsharp. When she did her doctoring, she exuded competence and control. But she’d lost that bright sparkle in her eye. What happened to you, Leah Mundy? he wondered.

Was it the death of her father, or had something else soured her spirits? Whatever it was, it had turned her from a smiling, eager young woman into a somber, authoritative physician whose only pleasure seemed to be in work.

Was that what made Leah Mundy unique? What made her seem so very sharp, so special, so competent?

Or was it that she held Carrie’s life in her hands?

With a muttered oath, he started pacing again. Carrie. For years she had been his quest, his purpose; sometimes she was his only reason for getting up in the morning.

She had been no more than nine years old when he’d first laid eyes on her. He recalled the moment vividly, because it was the first time in his life that he’d dared to believe angels were real. Even standing in the dingy foyer of the Chicago orphan asylum, Carrie seemed to transcend the squalor, her eyes fixed on some point far beyond the busy roomful of orphans and wardens.

She reminded Jackson of a painting he’d once seen in church—a pilgrim filled with the quiet ecstasy of her first sight of God. The other children whispered that Carrie—as beautiful and delicate as a moth—was strangely empty, that she had no soul.

He knew he was the only one who could protect her. He had endured hell in her defense: bloodied nose, broken finger, twisted arm. The rewards were sparing, but he cherished them all the more for their scarcity. She’d smile or squeeze his hand or whisper that she loved him—just often enough to make him believe her. And with just enough sincerity to make him believe she knew how to love.

He glanced again at the surgery door. He tried to think of Carrie having a kid, but his imagination wouldn’t cooperate. She wouldn’t know the first thing about babies. Ever since that accident back at St. I’s when an infant in Carrie’s ward had died and she’d been sent in disgrace to the isolation room, she’d never spoken of babies, never looked at one, never held one.

Then one day, Carrie had disappeared from the orphanage. He remembered waiting for her outside the girls’ ward as he always did, the corridor stinking of piss and borax. But she hadn’t come out. Brother Anthony had informed Jackson—cuffing him on the ear for the impertinence of asking—that Carrie had been adopted.

He’d felt something implode inside him. Not from the blow; he was used to beatings. But from the news Brother Anthony had delivered. Jackson knew what it meant when a girl like Carrie was “adopted.” Pimps were always on the lookout for new, pretty girls. Brother Anthony and Brother Brandon were always on the lookout for ways to line their pockets.

What happened next came back in broken images, shattered by the violence that followed. Sharp fragments of remembrance stabbed at the back of his mind.

He had lunged at Brother Anthony, seized the portly man, shoved him against the seeping wall of the corridor. “Where is she, you son of a bitch? Who took her?” Jackson’s fierce, boyish voice echoed through the cavernous hallway of the tenement.

“Long…gone, damn you to the eternal fires,” Brother Anthony choked out, his eyes bulging as Jackson’s thumbs pressed on his windpipe. Jackson was a strapping boy despite the poor diet and poorer treatment he’d suffered over the years.

“Where?” he persisted, feeling an ugly pressure behind his eyes. Rage swept over him like a forest fire, burning out of control. The fury was a powerful thing, and his young mind absorbed its force. This, he knew then, was what drove men to murder. “Where?” he asked again. “Where? Where?”

“Already heading…down the Big Muddy—” Brother Anthony stopped abruptly. Strong arms grabbed Jackson from behind. Fists clad in brass knuckles beat him senseless. He’d awakened hours or days later—he couldn’t tell which—in a windowless cell in the basement. One eye swollen shut, a constant ringing in his ears, broken rib stabbing at his midsection. It had taken him days to recover from the beating, and still longer to ambush the luckless boy who brought him his daily meal. Then Jackson had burst out into the street—to freedom, to danger, to the desperation of an outlaw on the run.

He drifted from town to town, from logging camps in the northern woods to army forts and outposts in the West, from little farming villages where people pretended not to see him to big dirty cities where everyone, it seemed, was part of a confidence game. Jackson had mastered the trade of a cardsharp and gunfighter. He crewed on Lake Michigan yachts in the summers, learning the way of life that had captured his imagination. He was like a leech, finding a host, sucking him dry, moving on.

A six-day card game had taken place on an eastbound train, and without planning to, Jackson had found himself in New York City. He had no liking for the city, but a force he didn’t understand and didn’t bother to fight had drawn him inexorably eastward along the low, sloping brow of Long Island.

He’d gotten his first glimpse of the sea on a Wednesday, and he’d stood staring at it as if he beheld the very face of God. The following Monday, he signed on a whaler as a common seaman. The next three years consisted of equal parts of glory and hell. When he returned, he knew two things for certain—he hated whaling beyond all imagining. And he loved the sea with a passion that bordered on worship.

But the unfinished quest for Carrie held him captive. Eventually, he had traced her. In New Orleans, while celebrating a tidy sweep at the poker table, he’d found himself a whore for the night, oddly comforted by the mindless, mechanical way the services were rendered and received. But in the morning, he’d opened his eyes to a shock as disturbing as a bucket of ice water.

“What the hell’s this?” he’d demanded, yanking at the silk ribbon around the whore’s neck. “Where’d you get it?”

The whore had clutched the object defensively. “Lady Caroline left it behind, said it was a good-luck charm so I took to wearing it.”

He grabbed the charm, stared at it for a long time. It was the dove he’d carved for Carrie so long ago. “Lady Caroline,” he said, hope burgeoning in his chest. “So where is she now?”

“Gone to Texas, last I heard, with Hale Devlin’s gang.”

Texas. And that had only been the beginning.

The shattering of glass jarred Jackson out of his reverie. With a curse, he looked at the framed tintype he’d been holding and saw that he’d broken it. An ice-clear web of cracks radiated from the center, distorting the picture of Leah and her father. Her smiling mouth was severed as if by violence; the father’s hand on her shoulder had been detached.

Painstakingly, Jackson removed the broken glass. The picture went back to normal—Leah, smiling, aglow with pride. Her father cold, distant. The scroll of a paper diploma clutched in her hand.

An educated woman. But could she save Carrie?

He shuddered from the memory of what he had found in Texas.

Could anyone?

Bone weary, bloodied to the elbows and filled with self-doubt, Leah peeled off her patent rubber gloves. She pressed her forehead against the damp wall of the surgery and closed her eyes.

Nearby, she could hear Sophie’s movements as she placed soiled sheeting and gowns into a pail of carbolic solution, then emptied a large porcelain container into a waste pail.

“You did your best. I watched you like a hawk on the hunt,” Sophie said. “Those fancy city doctors in Seattle couldn’t have done better.”

“Try telling that to Mr. Underhill,” Leah whispered. “Oh, God, God.” She forced her eyes open, made herself look at Sophie.

Her assistant was broad of face; she had wise dark eyes and an air of serenity that governed every move she made, every word she spoke. Half Skagit Indian and half French-Canadian, Sophie had been educated in boarding schools that taught her just enough to convince her that she belonged neither to the white nor the native world, but stood precariously between the two. It was an uncomfortable spot, but Leah, a misfit herself, felt sometimes that they were kindred spirits.

“It is the great curse of doctors,” Leah said, “that while most people have to die only once, a doctor dies many times over, each time she loses a patient.”

Sophie pressed her lips into a line, then spoke softly. “But it is the great reward of healers that each time you save a life, you yourself are reborn.” She looked down at the unmoving, pale face of Carrie Underhill. “Yes, you lost the baby. But you also saved Mrs. Underhill from bleeding to death. She’ll live to thank you. Perhaps to bear other children.”

Leah swallowed the lump in her throat. She knew some babies were never meant to be, especially when the mother suffered such precarious health. There was something puzzling about Carrie Underhill’s condition, something besides the pregnancy. A chronic complaint, perhaps. But what?

Did she drink calomel? Leah wondered. The purgative was still a popular folk remedy; it had been her father’s favorite prescription. This was the sort of thing he caused, she thought resentfully. She intended to keep Carrie under close observation.

The task at hand was more pressing, though. She had to face this woman’s husband. The baby’s father.

With a leaden heart, she helped Sophie finish clearing up. After Carrie was clad in a clean gown and lying on clean draperies, Leah went to the door and opened it. “Mr. Underhill?”

His head snapped around as if someone had punched him in the jaw. Weariness deepened the fan lines around his eyes and mouth, yet a beard stubble softened the effect; he appeared deceptively vulnerable. “Is she all right?”

Leah nodded. “She’s sleeping, but will probably awaken within the next hour.”

He closed his eyes and took a deep breath. “Good,” he said between his teeth. “Damn, that’s…good.” He opened his eyes. “Jesus. I feel like I just got dealt four aces.”

Leah cleared her throat. “She might suffer a headache, possibly vomiting, from the ether. You must watch her closely in case the bleeding starts again, but I don’t think it will.” She forced an encouraging smile. Something tender and desperate lived in Jackson Underhill’s haggard face. She wished she knew him well enough to take his hand, to hold it tight for a moment. Instead, she said, “I believe your wife will be fine. She needs plenty of bed rest and good food, and we’ll see to that.”

“Yes. All right.” His eyes closed again briefly. His knees wobbled.

“Sit down, Mr. Underhill. I can’t handle two patients tonight.”

He lowered himself to the wing chair and cradled his head in his hands, fingers splaying into his thick golden hair. “Didn’t know I was wound up so tight.” He glanced up at her. She felt an inner twist of compassion at the turbulence in his eyes. Those gunslinger eyes. The first time she had looked into them, she had nearly fainted from fright. Now she felt a chilly reluctance to tell him the rest.

“Thanks, Doc,” he said to her.

She nodded, holding the edge of the door, waiting. Waiting. Waiting for him to ask about the baby. He didn’t. He didn’t even seem to acknowledge its existence. She swallowed hard. “Mr. Underhill?”

“Yeah?”

She took a deep breath, sensing the harshness of carbolic and ammonia in her lungs. “I’m afraid I couldn’t save the baby.”

“The baby.” His soft voice held no expression, no hint of what he was feeling.

“I’m sorry. So terribly, terribly sorry.”

He stared at her for a long time, so long she wasn’t certain he’d heard and understood. Then at last he spoke. “You did your best, I reckon.”

In her travels with her father, she’d met her share of gamblers and gunslingers. They were men without souls, men who killed in the blink of an eye. Jackson T. Underhill was one of them. Until this moment, she hadn’t realized how badly she’d wanted him to be different—better, more worthy, more compassionate. But his attitude about the baby proved her wrong.

“I did my best, yes,” she said. “But like every physician, I have my limits. Some things just weren’t meant to be.” She decided not to tell him her concerns about Carrie. Not now, at least.

“I see.” He steepled the tips of his fingers together.

Mr. Underhill, you lost a child today. She didn’t say the words, but she wondered why he didn’t react more strongly. Perhaps his way of coping was to deny the baby had ever existed. After all, he’d only known about it for a day.

“What about the tonic your wife’s been taking?” Leah asked. “I really must know its contents.”

“Yeah, I’ll give you the bottle. It’s some patented medicine. Helps her relax. She’s always been…a nervous sort.”

“I’ll write off to the manufacturer and inquire about the contents.” Based on the substances she’d seen her father dispense, she was not optimistic. A lot of the patented remedies contained calomel purgatives and worse. She tried to smile encouragingly. “After the recovery, there’s no reason you and your wife can’t have more children.”

“There won’t be more children.” He slashed the air with his hand and lurched to his feet, the motion at once violent and desperate. “She almost died this time.”

Leah had heard the same words from other frightened husbands. The vow rarely lasted, though. Once the woman was up and about again, their husbands generally forgot the terror of the miscarriage. Still, she smiled gently and said, “Make no decisions now, Mr. Underhill. Everyone’s tired, and your wife has a long recovery ahead of her. You have plenty of time to think of the future.”

His eyes narrowed. “What’s that mean? A long recovery.”

“Weeks, at the very least. She’s lost a lot of blood, and she was underweight and anemic to begin with.”

“I can’t wait that long.”

Anger hardened inside Leah. “Then you’re taking a terrible risk with your wife’s health, sir,” she snapped. “Now, can you help bring her to her bed?”

“Doc.” His voice was flat, neutral. “Dr. Mundy.”

“Yes?”

“I wish you’d quit looking at me like that.”

“How am I looking at you, sir?”

“Like I was a snake under a rock.”

“If you see things from the perspective of a snake, that is your fault, not mine.”

He muttered beneath his breath, something she didn’t even want to hear, but he cooperated, helping her with Carrie.

“Will you stay, then?” Leah asked as they carefully tucked Carrie into bed. “No matter how long her recuperation takes?”

Jackson T. Underhill dragged his hand down his face in a gesture she was coming to recognize as his response to frustration. “Yeah,” he said at last. “Yeah, I’ll stay.”

Like a morning mist, a rare, dreamy wistfulness enveloped Leah as she made her way back from the Winfield place. She had driven herself in the buggy since the weather was fine and the vehicle unlikely to get mired. Ordinarily, Mr. Douglas from the boardinghouse did the driving. But he was getting on in years, and she tried not to drag him out of bed too early.