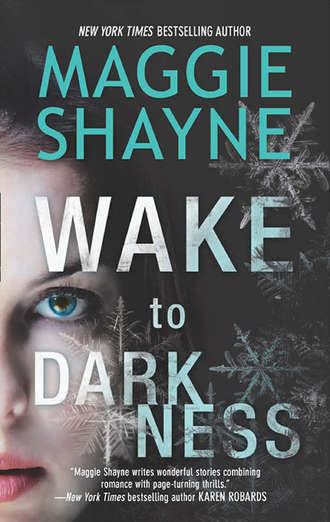

Wake to Darkness

Полная версия

Wake to Darkness

Жанр: приключениядетективызарубежные приключениятриллерысовременная зарубежная литературакниги о приключениях

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу