полная версия

полная версияMy Studio Neighbors

Let us consider the flower simply as a device to insure its own cross-fertilization. The insect is welcomed; it must alight and sip the nectar; in departing it must bear away this pollen upon its body, and convey it to the next Arethusa blossom which it visits, and leave it upon its stigma. These are the conditions expressed; and how admirably they are fulfilled we may observe when we examine flower after flower of a group, and find their nectaries drained, their anther cells empty, and pollen upon all their stigmas. The nectar is here secreted in a well—not very deep—and the depth of this nectar from the entrance is of great significance among all the flowers, having distinct reference to the length of the tongue which is expected to sip it. In the Arethusa, it is true, the butterfly or moth might sip at the throat of the flower, but the long tongues of these insects might permit the nectary to be drained without bringing their bodies in contact with the stigma. Smaller insects might creep into the nectary and sip without the intended fulfilment. It is clear that to neither of such visitors is the welcome extended. What, then, are the conditions embodied? The insect must have a tongue of such a length that, when in the act of sipping, its head must pass beyond the anther well into the opening of the flower. Its body must be sufficiently large to come in contact with the anther. Such requisites are perfectly fulfilled by the humblebee, and we may well hazard the prophecy that the Bombus is the welcomed affinity of the flower.

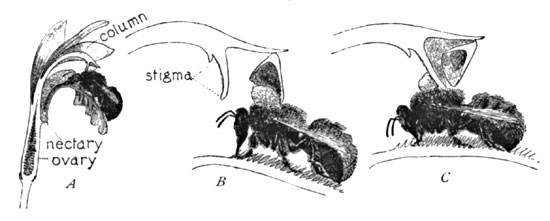

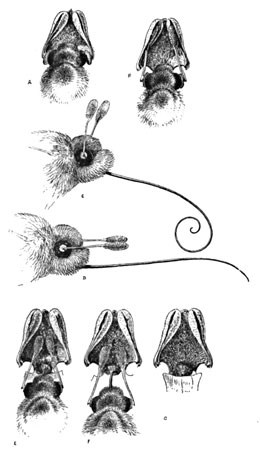

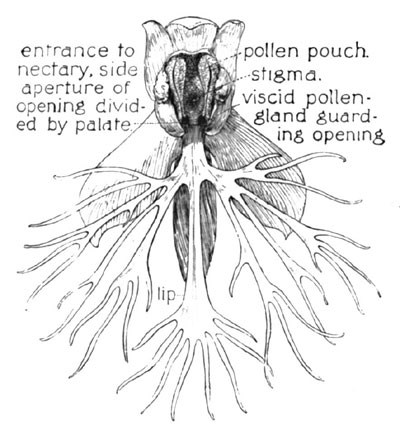

Fig. 4. Cross-fertilization of Arethusa

The diagrams (Fig. 4) sufficiently illustrate the efficacy of the beautiful plan involved. At A the bee is seen sipping the nectar. His forward movement thus far to this point has only seemed to press the edge of the anther inward, and thus keep it even more effectually closed. As the bee retires (B), the backward motion opens the lid, and the sticky pollen is thus brought against the insect's back, where it adheres in a solid mass. He now flies to the next Arethusa blossom, enters it as before, and in retiring slides his back against the receptive viscid stigma, which retains a portion of the pollen, and thus effects the cross-fertilization (C). Professor Gray surmised that the pollen was withdrawn on the insect's head, and it might be so withdrawn, but in other allied orchids of the tribe Arethusæ, however, in which the structure is very similar, the pollen is deposited on the thorax, and such is probably the fact in this species. In either case cross-fertilization would be effected. Nothing else is possible in the flower, and whether it is Bombus or not that effects it, the method is sufficiently evident.

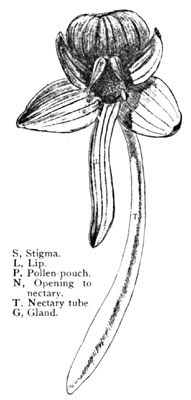

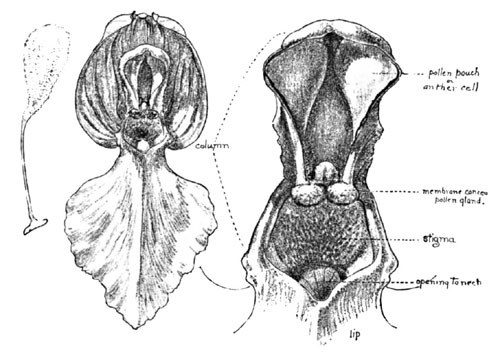

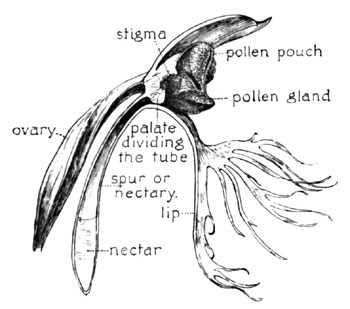

Fig. 5.

Habenaria Orbiculata.

A Single Flower Enlarged

Having thus had one initiation into this most enticing realm of riddles, each successive orchid whose structure we examine from this stand-point becomes a most interesting, perhaps a fresh, problem, whose assumed solution may often be verified by studying the insect in its haunts. Darwin thus foretold the precise manner of the cross-fertilization of Habenaria mascula, and also the insect agent, simply by the structural prophecy of the flower itself.

Suppose, for example, an unknown orchid blossom to be placed in our hands. Its nectary tube is five inches in length, and as slender as a knitting-needle. The nectar is secreted far within its lip. The evolution of the long nectary implies an adaptation to an insect's tongue of equal length. What insect has a tongue five inches long, and sufficiently slender to probe this nectary? The sphinx-moth only. Hence we infer the sphinx-moth to be the insect complement to the blossom, and we may correctly infer, moreover, that the flower is thus a night-bloomer. Examination of the flower, with the form of this moth in mind, will show other adaptations to the insect's form in the position of pollen and stigma, looking to the flower's cross-fertilization. In some cases this is effected by the aid of the insect's tongue; in others, by its eyes.

In our own native orchids we have a remarkable example of the latter form in the Habenaria orbiculata, whose structure and mechanism have also been admirably described by Asa Gray.

All orchid-hunters know this most exceptional example of our local flora, and the thrill of delight experienced when one first encounters it in the mountain wilderness, its typical haunt, is an event to date from—its two great, glistening, fluted leaves, sometimes as large as a dinner-plate, spreading flat upon the mould, and surmounted by the slender leafless stalk, with its terminal loose raceme of greenish-white bloom.

Orchis Spectabilis

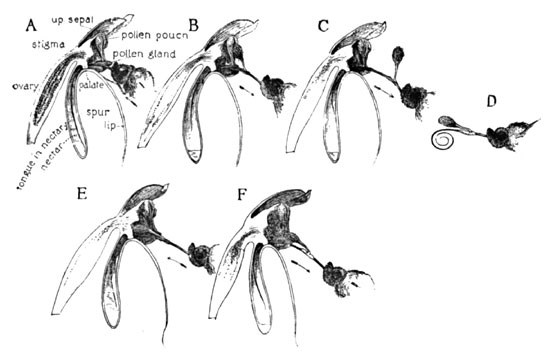

Fig. 6. Cross-fertilization of H. Orbiculata (Sphinx-moth)

A single blossom of the species is shown in Fig. 5, the parts indexed. The opening to the nectary is seen just below the stigmatic surface, the nectary itself being nearly two inches in length. The pollen is in two club-like bodies, each hidden within a fissured pouch on either side of the stigma, and coming to the surface at the base in their opposing sticky discs as shown. Many of the group Habenaria or Platanthera, to which this flower belongs, are similarly planned. But mark the peculiarly logical association of the parts here exhibited. The nectary implies a welcome to a tongue two inches long, and will reward none other. This clearly shuts out the bees, butterflies, and smaller moths. What insect, then, is here implied? The sphinx-moth again, one of the lesser of the group. A larger individual might sip the nectar, it is true, but its longer tongue would reach the base of the tube without effecting the slightest contact with the pollen, which is of course the desideratum here embodied, and which has reference to a tongue corresponding to the length of the nectary. There are many of these smaller sphinxes. Let us suppose one to be hovering at the blossom's throat. Its slender capillary tongue enters the opening. Ere it can reach the sweets the insect's head must be forced well into the throat of the blossom, where we now observe a most remarkable special provision, the space between the two pollen discs being exactly adjusted to the diameter of the insect's head. What follows this entrance of the moth is plainly pictured in the progressive series of illustrations (Fig. 6). A represents the insect sipping; the sticky discs are brought in contact with the moth's eyes, to which they adhere, and by which they are withdrawn from their pouches as the moth departs (B). At this time they are in the upright position shown at C, but in a few seconds bend determinedly downward and slightly towards each other to the position D. This change takes place as the moth is flitting from flower to flower. At E we see the moth with its tongue entering the nectary of a subsequent blossom. By the new position of the pollen clubs they are now forced directly against the stigma (E). This surface is viscid, and as the insect leaves the blossom retains the grains in contact (F), which in turn withdraw others from the mass by means of the cobwebby threads by which the pollen grains are continuously attached. At G we see the orchid after the moth's visit—the stigma covered with pollen, and the flower thus cross-fertilized.

In effecting the cross-fertilization of one of the younger flowers its eyes are again brought into contact with this second pair of discs, and these, with their pollen clubs, are in turn withdrawn, at length perhaps resulting in such a plastering of the insect's eyes as might seriously impair its vision, were it not fortunately of the compound sort.

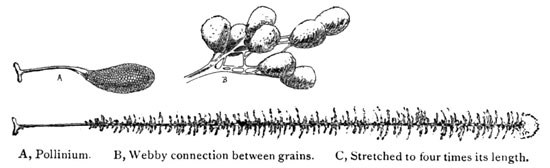

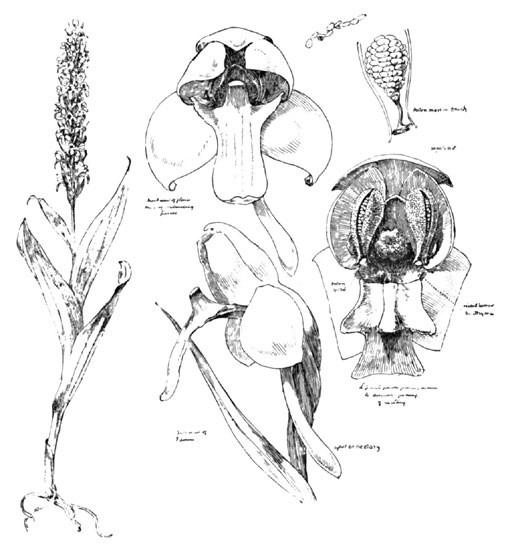

Fig. 7. The Flower and Column of Orchis Spectabilis, Enlarged

In another allied example of the orchids—the Showy Orchid—we have, however, what would appear a clear adaptation to the head of a bee, though one which might also avail of the service of an occasional butterfly. A group of this beautiful species is shown in my illustration. A favored haunt is the dark damp woods, especially beneath hemlocks, and with its deep pink hood and pure white lip is quite showy enough to warrant its specific title, "spectabilis." An enlarged view of the blossom is seen in Fig. 7, and in Fig. 8 a still greater enlargement of the column.

Fig. 8. Orchis Spectabilis

Fig. 9.

Position of Pollen of Orchis Spectabilis

Withdrawn on Pencil

I have seen many specimens with the pollen masses withdrawn, and others with their stigmas well covered with the grains. Though I have never seen an insect at work upon it in its haunt, the whole form of the opening of the flower would seem to imply a bee, particularly a bumblebee. If we insert the point of a lead-pencil into this opening, thus imitating the entrance of a bee, its bevelled surface comes in contact with the viscid discs by the rupture of a veil of membrane, which has hitherto protected them. The discs adhere to the pencil, and are withdrawn upon it (Fig. 9). At first in upright position, they soon assume the forward inclination, as previously described. The nectary is about the length of a bumblebee's tongue, and is, moreover, so amply expanded at the throat below the stigma as to comfortably admit its wedge-shaped head. The three progressive diagrams (Fig. 10) indicate the result in the event of such a visit.

The pollen discs are here very close together, and are protected within a membraneous cup, in which they sit as in a socket. As the insect inserts his head at the opening (A) it is brought against this tender membrane, which ruptures and exposes the viscid glands of the pollen masses, which become instantly attached to the face or head, perhaps the eyes, of the burly visitor. As the insect retreats from the flower, one or both of the pollinia are withdrawn, as at B. Then immediately follows a downward movement, which exactly anticipates the position of the stigma, and as the bee enters the next flower the pollen clubs are forced against it (C), as in the previous example.

In the case of a smaller bee visiting the flower, the insect would find it necessary to creep further into the opening, and thus might bring its thorax against the pollen-glands. In either case the change of position in the pollinia would insure the same result.

Fig. 10. The Cross-fertilization of Orchis Spectabilis

Fig. 10. The Cross-fertilization of Orchis Spectabilis

We have thus seen adaptation to the thorax, the eyes, and the face in the three examples given. And the entrance of the flower in each instance is so formed as to insure the proper angle of approach for the insect for the accomplishment of the desired result. This direct approach, so necessary in many orchids, is insured by various devices—by the position of the lip upon which the insect must alight; by the narrowed entrance of the throat of the flower in front of the nectary; by a fissure in the centre of the lip, by which the tongue is conducted, etc.

Many other species allied to the above possess similar devices, with slight variations; and there is still another group whose structure is distinctly adjusted to the tongues of insects—adaptations not merely of position of pollen masses, but even to the extent of a special modification in the entrance to the flower and the shape of the sticky gland, by which it may more securely adhere to that sipping member.

In the common pretty Purple-fringed Orchid, whose dense cylindrical spikes of plumy blossoms occasionally empurple whole marshes, we have an arrangement quite similar to the H. orbicularis just described, with the exception that the pollen-pouches are almost parallel, and not noticeably spread at the base (Fig. 11). In this case the eyes of sipping butterflies occasionally get their decoration of a tiny golden club, but more frequently their tongues.

Fig. 11. The Purple-fringed Orchid

If, however, the butterfly should approach directly in front of the flower, as in a larger blossom he would be most apt to do, he might sip the nectar indefinitely and withdraw his tongue without bringing it in contact with the viscid pollen discs. But in the dense crowding of the flowers, over which the insect flutters indiscriminately, the approach is oftenest made obliquely, and thus the tongue brushes the disc on the side approached, and the pollen mass is withdrawn. But an examination of this orchid affords no pronounced evidence of any specific intention. There is no unmistakable sign to demonstrate which approach is preferred or designed by the flower, and this dependence on the insect's tongue or eye would seem to be left to chance.

In another closely allied species, however, we have a distinct provision which insures the proper approach of the tongue—one of many similar devices by which the tongue is conducted directly to one or the other of the pollen discs.

Fig. 12. The Ragged Orchid (Front Section)

This is the Ragged Orchid, a near relative of the foregoing, H. psycodes, but far less fortunate in its attributes of beauty, its long scattered spike of greenish-white flowers being so inconspicuous in its sedgy haunt as often to conceal the fact of its frequency. Its individual flower is shown enlarged at Fig. 12—the lip here cut with a lacerated fringe (H. lacera). The pollen-pouches approach slightly at the base, directly opposite the nectary, where the two viscid pollen-glands stand on guard. Now were the opening of the nectary at this point unimpeded, the same condition would exist as in the H. psycodes—the tongue might be inserted between the pollen discs and withdrawn without touching them. But here comes the remarkable and very exceptional provision to make this contact a certainty—a suggestive structural feature of this flower of which I am surprised to find no mention either in our botanies or in the literature of cross-fertilization, so far as I am familiar with its bibliography. Even Dr. Gray's description of the fertilization device of this species makes no mention of this singular and very important feature. The nectary here, instead of being freely open, as in other orchids described, is abruptly closed at the central portion by a firm protuberance or palate, which projects downward from the base of the stigma, and closely meets the lip below.

The throat of the nectary, thus centrally divided, presents two small lateral openings, each of which, from the line of approach through the much-narrowed entrance of the flower, is thus brought directly beneath the waiting disc upon the same side. The structure is easily understood from the two diagrams Figs. 12 and 13, both of which are indexed.

Fig. 13. The Ragged Orchid (Profile Section)

The viscid pollen-gland is here very peculiarly formed, elongated and pointed at each end, and it is not until we witness the act of its removal on the tongue of the butterfly that we can fully appreciate its significance.

I have often seen butterflies at work upon this orchid, and have observed their tongues generously decorated with the glands and remnants of the pollen masses.

The series of diagrams (Fig. 14) will, I think, fully demonstrate how this blossom utilizes the butterfly. At A we see the insect sipping, its tongue now in contact with the elongated disc, which adheres to and clasps it. The withdrawal of the tongue (B) removes the pollen from its pouch. At C it is seen entirely free and upright, from which position it quickly assumes the new attitude shown at D. As the tongue is now inserted into the subsequent blossom this pollen mass is thrust against the stigma (E), and a few of the pollen grains are thus withheld upon its viscid surface as the insect departs (F).

In this orchid we thus find a distinct adaptation to the tongue of a moth or butterfly.

Another similar device for assuring the necessary side approach is seen in H. flava (Fig. 15), a yellowish spiked species, more or less common in swamps and rich alluvial haunts.

Fig. 14. The Ragged Orchid (H. Lacera) and the Butterfly's Tongue. Cross-fertilization

Professor Wood remarks, botanically, "The tubercle (or palate) of the lip is a remarkable character." But he, too, has failed to note the equally remarkable palate of the ragged orchid, just described, both provisions having the same purpose, the insurance of an oblique approach to the nectary. In H. flava this "tubercle," instead of depending from the throat, grows upward from the lip, and, as we look at the flower directly from the front, completely hides the opening to the nectary, and an insect is compelled to insert its tongue on one side, which direction causes it to pass directly beneath the pollen disc, as in H. lacera, and with the same result.

Fig. 15. The Yellow Orchid (H. Flava)

The Ragged Orchid (H. Lacera)

Of all our native orchids, at least in the northeastern United States, the Cypripedium, or Moccasin-Flower, is perhaps the general favorite, and certainly the most widely known. This is readily accounted for not only by its frequency, but by its conspicuousness. The term "moccasin-flower" is applied more or less indiscriminately to all species. The flower is also known as the ladies'-slipper, more specifically Venus's-slipper—as warranted by its generic botanical title—from a fancied resemblance in the form of the inflated lip, which is characteristic of the genus. We may readily infer that the fair goddess was not consulted at the christening.

There are six native species of the cypripedium in this Eastern region, varying in shape and in color—shades of white, yellow, crimson, and pink. The mechanism of their cross-fertilization is the same in all, with only slight modifications.

The most common of the group, the C. acaule, most widely known as the moccasin-flower, whose large, nodding, pale crimson blooms we so irresistibly associate with the cool hemlock woods, will afford a good illustration.

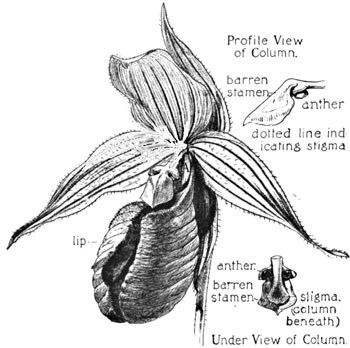

The lip in all the cypripediums is more or less sac-like and inflated. In the present species, C. acaule, however, we see a unique variation, this portion of the flower being conspicuously bag-like, and cleft by a fissure down its entire anterior face. In Fig. 16 is shown a front view of the blossom, showing this fissure. The "column" (B) in the cypripedium is very distinctive, and from the front view is very non-committal. It is only as we see it in side section, or from beneath, that we fully comprehend the disposition of stigma and pollen. Upon the stalk of this column there appear from the front three lobes—two small ones at the sides, each of which hides an anther attached to its under face—the large terminal third lobe being in truth a barren rudiment of a former stamen, and which now overarches the stigma. The relative position of these parts may be seen in the under view.

Cypripedium Acaule

The anthers in this genus, then, are two, instead of the previous single anther with its two pollen-cells. The pollen is also quite different in its character, being here in the form of a pasty mass, whose entire exposed surface, as the anther opens, is coated with a very viscid gluten.

Fig. 16. Moccasin-flower (C. Acaule)

With the several figures illustrating the cross-fertilization, the reader will readily anticipate any description of the process, and only a brief commentary will be required in my text.

I have repeatedly examined the flowers of C. acaule in their haunts, have observed groups wherein every flower still retained its pollen, others where one or both pollen masses had been withdrawn, and in several instances associated with them I have observed the inflated lip most outrageously bruised, torn, and battered, and occasionally perforated by a large hole. I had observed these facts in boyhood. The inference, of course, was that some insect had been guilty of the mutilation; but not until I read Darwin's description of the cross-fertilization of this species did I realize the full significance of these telltale evidences of the escape of the imprisoned insect. Since that time, many years ago, I have often sat long and patiently in the haunt of the cypripedium awaiting a natural demonstration of its cross-fertilization, but as yet no insect has rewarded my devotion.

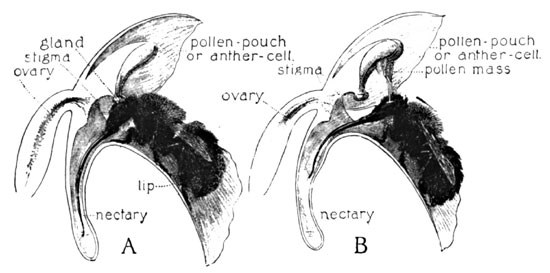

Fig. 17.

The Bee Imprisoned in the Lips of Cypripedium

At length, in hopelessness of reward by such means, I determined to see the process by more prosaic methods. Gathering a cluster of the freshly opened flowers, which still retained their pollen, I took them to my studio. I then captured a bumblebee, and forcibly persuaded him to enact the demonstration which I had so long waited for him peaceably to fulfil. Taking him by the wings, I pushed him into the fissure by which he is naturally supposed to enter without persuasion. He was soon within the sac, and the inflexed wings of the margin had closed above him, as shown in section, Fig. 17. He is now enclosed in a luminous prison, and his buzzing protests are audible and his vehemence visible from the outside of the sac. Let us suppose that he at length has become reconciled to his condition, and has determined to rationally fulfil the ideal of his environment, as he may perhaps have already done voluntarily before. The buzzing ceases, and our bee is now finding sweet solace for his incarceration in the copious nectar which he finds secreted among the fringy hairs in the upper narrowed portion of the flower, as shown at Fig. 18 A. Having satiated his appetite, he concludes to quit his close quarters. After a few moments of more vehement futile struggling and buzzing, he at length espies, through the passage above the nectary fringe, a gleaming light, as from two windows (A). Towards these he now approaches. As he advances the passage becomes narrower and narrower, until at length his back is brought against the overhanging stigma (Fig. 18 B). So narrow is the pass at this point that the efforts of the bee are distinctly manifest from the outside in the distension of the part and the consequent slight change in the droop of the lip. In another moment he has passed this ordeal, and his head is seen protruding from the window-like opening (A) on one side of the column. But his struggles are not yet ended, for his egress is still slightly checked by the narrow dimensions of the opening, and also by the detention of the anther, which his thorax has now encountered. A strange etiquette this of the cypripedium, which speeds its parting guest with a sticky plaster smeared all over its back. As the insect works its way beneath the viscid contact, the anther is seen to be drawn outward upon its hinge, and its yellow contents are spread upon the insect's back (Fig. 18 C), verily like a plaster. Catching our bee before he has a chance to escape with his generous floral compliments, we unceremoniously introduce him into another cypripedium blossom, to which, if he were more obliging, he would naturally fly. He loses no time in profiting by his past experience, and is quickly creeping the gantlet, as it were, or braving the needle's eye of this narrow passage. His pollen-smeared thorax is soon crowding beneath the overhanging stigma again, whose forward-pointed papillæ scrape off a portion of it (Fig. 18 B), thus insuring the cross-fertilizing of the flower, the bee receiving a fresh effusion of cypripedium compliments piled upon the first as he says "good-bye." It is doubtful whether in his natural life he ever fully effaces the telltale effects of this demonstrative au revoir.