Полная версия

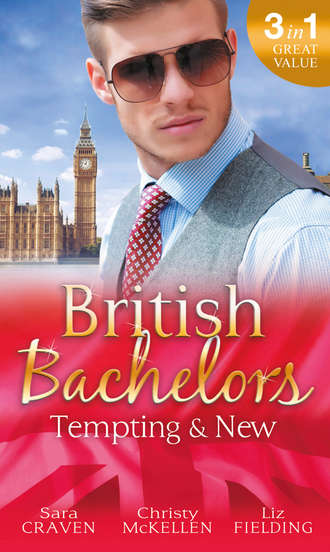

British Bachelors: Tempting & New: Seduction Never Lies / Holiday with a Stranger / Anything but Vanilla...

British Bachelors: Tempting & New

Seduction Never Lies

Sara Craven

Holiday with a Stranger

Christy McKellen

Anything but Vanilla…

Liz Fielding

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Seduction Never Lies

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Holiday with a Stranger

About the Author

Dedication

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

Anything but Vanilla…

Back Cover Text

About the Author

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

Copyright

Seduction Never Lies

Sara Craven

SARA CRAVEN was born in South Devon and grew up in a house full of books. She worked as a local journalist, covering everything from flower shows to murders, and started writing for Mills & Boon in 1975. When not writing, she enjoys films, music, theatre, cooking, and eating in good restaurants. She now lives near her family in Warwickshire. Sara has appeared as a contestant on the former Channel Four game show Fifteen to One, and in 1997 was the UK television Mastermind champion. In 2005 she was a member of the Romantic Novelists’ team on University Challenge – the Professionals.

CHAPTER ONE

OCTAVIA DENISON FED the last newsletter through the final letter box in the row of cottages and, with a sigh of relief, remounted her bicycle and began the long hot ride back to the Vicarage.

There were times, and this was one of them, when she wished the Reverend Lloyd Denison would email his monthly message to his parishioners instead.

‘After all,’ as Patrick had commented more than once, ‘Everyone in the village must have a computer these days.’

But her father preferred the personal touch, and when Tavy came across someone like old Mrs Lewis longing for a chat over a cup of tea because her niece was away on holiday, and who certainly had no computer or even a mobile phone, she supposed wryly that Dad had a point.

All the same, this was not an ideal day for a cycle tour of the village on an old boneshaker.

For once, late May had produced a mini-heatwave with cloudless skies and temperatures up in the Seventies, which had also managed to coincide with Greenbrook School’s half-term holiday.

Nice for the kids, thought Tavy as she pedalled but, for her, it would be business as usual tomorrow.

Her employer, Eunice Wilding, paid her what she considered was the appropriate rate for a young and unqualified school secretary, but she expected, according to the local saying, ‘her cake for her ha’penny’.

But at the time the job had seemed a lifeline in spite of the poor pay. One small ray of light in the encircling darkness of the stunned grief she shared with her father at her mother’s sudden death from a totally unsuspected heart condition.

He’d protested, of course, when she’d announced she was giving up her university course to come home and keep house for him, but she’d read the relief in his eyes, swallowed her regrets, and set herself to rebuilding both their lives, cautiously tackling the parish tasks that her mother had fulfilled with such warmth and good humour, while discovering that, in Mrs Wilding’s vocabulary, ‘assistant’ was another word for ‘dogsbody’.

But in spite of its drawbacks, the job enabled her to maintain a restricted level of independence and pay a contribution to the Vicarage budget.

In return, she was expected to put in normal office hours, five and a half days a week, with just a fortnight’s holiday taken in two weekly instalments in spring and autumn, and far removed from the lengthy vacations enjoyed by the teaching staff.

And half-term breaks did not feature either, so this particular afternoon was a concession, while Mrs Wilding conducted her usual staff room inquisition into the events of the past weeks, and outlined the progress she expected in the next half.

It was her ability to achieve these targets that had made Greenbrook School an undoubted success in spite of its high fees. Mrs Wilding herself did not teach, calling herself the Director rather than the headmistress, but she had a knack for picking those that could, and even the most unpromising pupils were given the start they needed.

When she eventually retired, the school would continue to flourish under the leadership of Patrick, her only son, who’d returned from London the previous year to become a partner in an accountancy firm in the nearby market town, and who already acted as Greenbrook’s part-time bursar.

And his wife, when he had one, would also have a part to play, thought Tavy, feeling an inner glow that had nothing to do with the sun.

She’d known Patrick all her life of course, and he’d been the object of her first early teen crush. While her school friends giggled and fantasised over pop stars and soap actors, her sole focus had been the tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed Adonis who lived in her own village.

Although it might as well have been one of the moons of Jupiter for all the notice he took of her. She could remember basking for weeks in the memory of a casual ‘Thanks’ when she’d been ball girl for his final match in the annual village tennis tournament. Could recall the excitement building as the university vacations approached and she knew he would be home, but also crying herself to sleep when he spent his holidays elsewhere, as he often did.

But then real life in the shape of public examinations and career choices intervened and took priority, so that when she heard her father mention casually to her mother that Patrick was off to the States for some form of post-graduate study, the worst she had to suffer was a small pang of regret.

Since that time, he’d come back only for fleeting visits, and the last thing Tavy expected was that he would ever return to live in the area. Yet six months ago that was exactly what had happened.

And the first she’d known of it was when his mother brought him one afternoon into the cubbyhole which served as her office.

She’d said rather stiffly, ‘Patrick, I don’t know if you remember Octavia Denison...’

‘Of course, I do.’ His smile seemed to reach out and touch her, as she’d seen it do so often to others in the past. But, until that moment, never to her. ‘We’re old friends.’ Adding, ‘You look terrific, Tavy.’

She’d felt the swift colour burn in her face. Fought to keep her voice steady as she returned, ‘It’s good to see you again, Patrick.’

Knowing that she had not bargained for precisely how good. And feeling a swift stab of anxiety in consequence.

After that, he seemed to make a point of popping in to see her whenever he was at the school, perching on the corner of her desk to chat easily as if that past friendship had really existed, and she hadn’t simply been ‘that skinny red-haired kid from the Vicarage’ as one of the girls in his crowd had once described her, loudly enough to be overheard.

Tavy had remained on her guard, polite but not encouraging, her instinct telling her that Mrs Wilding was unlikely to approve of such fraternisation. Not even sure that she approved of it herself, even if the bursarship gave him an excuse for being there.

So, when Patrick eventually invited her to have dinner with him, her refusal was immediate and definite.

‘But why?’ he asked plaintively. ‘You do eat, don’t you?’

She hesitated. ‘Patrick, I work for your mother. It wouldn’t be—appropriate for you to take out the hired help.’

Besides I need this job, because finding another in the same radius is by no means a certainty...

He snorted. ‘For heaven’s sake, what century are we living in? And Ma will be cool about it, I guarantee.’

But she remained adamant, only to discover that he was adopting a similar stance. And, finally, at the third time of asking, and in spite of her lingering misgivings, she agreed.

It occurred to her while she was getting ready, searching the wardrobe for the one decent dress she possessed and praying it still fitted, that she hadn’t actually been out with a man since those few short months at university when she’d had a few casual but enjoyable dates with a fellow student called Jack.

Looking back, she could see that these might have developed into something more serious, if Fate hadn’t intervened with such devastating cruelty.

Since then nothing—and no one.

For one thing, there were few single and available men in the neighbourhood. For another, coping with her job, plus the cooking and housework at the Vicarage and helping out with parish duties left her too tired to go looking, even if she’d had the time or inclination.

She could only hope that Patrick hadn’t tuned into this somehow and invited her out of pity.

If so, he’d kept it well-hidden during an evening it still made her smile to remember. He’d taken her to a small French restaurant in Market Tranton where they’d begun with a delicious garlicky pâté before moving on to confit du canard, served with green beans and a gratin dauphinois, with a seriously rich chocolate mousse to complete the meal. All washed down with a soft, fruity Bergerac wine.

A meal from the Dordogne region, he’d told her, and probably the only one she’d ever taste, she thought later, as she drifted off to sleep.

After that, they’d started seeing each other on a regular basis, although when they encountered each other in working hours, it was always strictly business. And in spite of his assurances, Tavy wasn’t at all sure that her employer was actually aware of the whole situation. Certainly Mrs Wilding made no reference to it, but maybe that was because she considered it unimportant. A temporary aberration on Patrick’s part which would soon pass.

Except it showed no sign of doing so, although so far he’d made no serious attempt to get her into bed, as she’d half expected. And, perhaps, wanted, having no real wish to remain the only twenty-two-year-old virgin in captivity.

And while she knew she could not expect her father to approve, he’d been enough of a realist to impose no taboos in his pre-university advice. Just a quietly expressed hope that she would always maintain her self-respect.

So, sleeping with a man with whom she shared a settled relationship could hardly damage that, she told herself. In many ways it would be an affirmation. A promise for the future.

Although all their meetings were still taking place well away from the village.

When, at last, she’d tackled him about this, he’d admitted ruefully that he’d been deliberately keeping the situation under wraps. Saying that his mother had a lot on her mind at the moment, and he was waiting for the right moment to tell her about their plans.

If, of course, there was ever going to be a right moment, Tavy had thought, sighing inwardly.

Mrs Wilding cultivated sweetness like other people cultivate window-boxes. For outward show.

How she would react if and when she discovered her assistant might one day be transformed from drudge to daughter-in-law was anyone’s guess, but Tavy’s money would be on ‘badly’.

But I’ll worry about that when I have to, she thought, putting up a hand to wipe away the sweat trickling down into her eyes.

The first inkling she had that a vehicle was behind her came with a loud blast on its horn. Gasping, she wobbled precariously for a moment then got her bike back under control before it veered into the ditch.

The car that had startled her, a sleek open-top sports model, overtook her and drew up a few yards ahead.

‘Hi, Octavia.’ The driver turned to address her, languidly pushing her designer sunglasses up on to smooth blonde hair. ‘Still using that museum piece to get around?’

Striving to recover her temper along with her balance, Tavy groaned inwardly.

Fiona Culham that was, she thought with resignation. She would have recognised those clipped brittle tones anywhere. Just not anticipated hearing them round here any time soon, and would have preferred it kept that way.

Reluctantly, she dismounted and pushed her cycle level with the car. ‘Hello, Mrs Latimer.’ She kept her tone civil but cool, reflecting that although Fiona was only two years her senior, the use of Christian names had never been reciprocal. ‘How are you?’

‘I’m fine, but you’re a little behind the times. Didn’t you know that I’m using my maiden name again now that the divorce is going through?’

Heavens to Betsy, thought Tavy in astonishment. You were only married eighteen months ago.

Aloud, she said, ‘No I hadn’t heard, but I’m very sorry.’

Fiona Culham shrugged. ‘Well, don’t be, please. It was a hideous mistake, but you can’t win them all.’

The hideous mistake—an enormous London wedding to the wealthy heir to a stately home, with minor royalty present—had been plastered all over the newspapers, and featured in celebrity magazines. The bride, described as radiant, had apparently been photographed before she saw the error of her ways.

‘A little long-distance excitement for us all,’ the Vicar had remarked, at the time, laying his morning paper aside. He sighed. ‘And I can quite see why Holy Trinity, Hazelton Magna, would not have done for the ceremony.’

And just as well, Tavy thought now, knowing how seriously her father took the whole question of marriage, and how grieved he became when relationships that had started out with apparent promise ended all too soon on the rocks.

She cleared her throat. ‘It must be very stressful for you. Are you back for a holiday?’

‘On the contrary,’ Fiona returned. ‘I’m back for good.’ She looked Tavy over, making her acutely aware that some of her auburn hair had escaped from its loose topknot and was hanging in damp tendrils round her face. She also knew that her T-shirt and department store cut-offs had been examined, accurately priced and dismissed.

Whereas Fiona’s sleek chignon was still immaculate, her shirt was a silk rainbow, and if Stella McCartney made designer jeans, that’s what she’d be wearing.

‘So,’ the other continued. ‘What errand of mercy are you engaged with today? Visiting the sick, or alms for the poor?’

‘Delivering the village newsletter,’ Tavy told her expressionlessly.

‘What a dutiful daughter, and no time off for good behaviour.’ Fiona let in the clutch and engaged gear. ‘No doubt I’ll see you around. And I really wouldn’t spend any more time in this sun, Octavia. You look as if you’ve reached melting point already.’

Tavy watched the car disappear round a bend in the lane, and wished it would enter one of those time zones where people mysteriously vanished, to reappear nicer and wiser people years later.

Though no amount of time bending would improve Fiona, the spoiled only child of rich parents, she thought. It was Fiona who’d made the skinny red-haired kid remark, while Tavy was helping with the tombola at a garden party at White Gables, her parents’ home.

Norton Culham had married the daughter of a millionaire, and her money had helped him buy a rundown dairy farm in Hazelton Parva and transform it into a major horse breeding facility.

Success had made him wealthy, but not popular. Tolerant people said he was a shrewd businessman. The less charitable said he was a miserable, mean-spirited bastard. And his very public refusal to contribute as much as a penny to the proposed restoration fund for Holy Trinity, the village’s loved but crumbling Victorian church had endeared him to no one. Neither had his comment that Christianity was an outdated myth.

‘It’s a free country. He can think what he likes, same as the rest of us,’ said Len Hilton who ran the pub. ‘But there’s no need to bellow it at the Vicar.’ And he added an uncomplimentary remark about penny-pinching weasels.

But no pennies had ever been pinched where Fiona was concerned, thought Tavy. After she’d left one of England’s most expensive girls’ schools, there’d been a stint in Switzerland learning cordon bleu cookery, among other skills that presumably did not include being pleasant to social inferiors.

However, Fiona had been right about one thing, she thought, easing her T-shirt away from her body as she remounted her bike. She was indeed melting. However there was a cure for that, and she knew where to find it.

Accordingly when she reached a fork in the lane a few hundred yards further on, she turned left, a route which would take her past the high stone wall which encircled the grounds of Ladysmere Manor.

As she reached the side gate, hanging sadly off its hinges, she saw that the faded ‘For Sale’ sign had fallen off and was lying in the long grass. Dismounting, Tavy picked it up and propped it carefully against the wall. Not that it would do much good, she acknowledged with a sigh.

The Manor had been on the market and standing empty and neglected for over three years now, ever since the death of Sir George Manning, a childless widower. His heir, a distant cousin who lived in Spain with no intention of returning, simply arranged for the contents to be cleared and auctioned, then, ignoring the advice of the agents Abbot and Co, put it up for sale at some frankly astronomical asking price.

It was a strange mixture of a house. Part of it was said to date from Jacobean times, but since then successive generations had added, knocked down, and rebuilt, leaving barely a trace of the original dwelling.

Sir George had been a kindly, expansive man, glad to throw his grounds open to the annual village fête and allow the local Scouts and Guides to camp in his woodland, and whose Christmas parties were legendary.

But without him, it became very quickly a vacant and overpriced oddity, as his cousin refused point blank to offer the same hospitality.

At first, there’d been interest in the Manor. Someone was said to want it for a conference centre. A chain of upmarket nursing homes had made an actual offer. A hotel group was mentioned and there were even rumours of a health spa.

But the cousin in Spain obstinately refused to lower his asking price or consider offers, and gradually the viewings petered out and stopped, reducing the Manor from its true place as the hub of the village to the status of white elephant.

Tavy had always loved the house, her childish imagination transforming its eccentricities into a place of magic, like an enchanted castle.

Now, as she squeezed round the gate and began to pick her way through the overgrown jungle that had once been a garden, she thought sadly that it would take not just magic but a miracle to bring the Manor back to life.

Over the tangle of bushes and shrubs, she could see the pale shimmering green of the willows that bordered the lake. At the beginning, volunteers from the village had come and cleared the weeds from the water, as well as mowing the grass and cutting back the vegetation in front of the house, but an apologetic letter from Abbot and Co explaining that there was no insurance cover for accidents had put a stop to that.

But the possibility of weeds was no deterrent for Tavy. She’d encountered them before in previous summers when the temperature soared, and all that mattered was the prospect of cool water against her heated skin. And because she always had the lake to herself, she never had to bother with a swimsuit.

It had become a secret pleasure, not to be indulged too often, of course, but doing no harm to anyone. In a way, she felt as if her occasional presence was a reassurance to the house that it had not been entirely forgotten.

And nor was the Lady, who’d been there for nearly three hundred years, and therefore must find all these recent months very dull without company, standing naked on her plinth looking down at the water, one white marble arm concealing her breasts, her other hand chastely covering the junction of her thighs.

Tavy had always been thankful that the statue hadn’t been sent to the saleroom, along with Sir George’s wonderful collection of antique musical boxes, and his late wife’s beautifully furnished Victorian doll’s house.

You had a lucky escape there, Aphrodite or Helen of Troy, or whoever you’re supposed to be, she said under her breath as she took off her clothes, putting them neatly on the plinth before unclipping her hair. Because the lake wouldn’t be the same without you.

The water wasn’t just cool, it was very cold, and Tavy gasped as she took her first cautious steps from the sloping bank. As she waded in more deeply, the first shock wore off, the chill becoming welcome, until with a small sigh of pleasure, she submerged completely.

Above her, she could see the sun on the water in a dazzle of green and gold and she pushed up towards it, throwing her head back as she lifted herself above the surface in one graceful joyous burst.

And found herself looking at darkness. A black pillar against the sun where there should only have been blanched marble.

She lifted her hands, almost frantically dragging her hair back from her face, and rubbing water from the eyes that had to be playing tricks with her.

But she wasn’t hallucinating. Because the darkness was real. Flesh and blood. A man, his tall, broad-shouldered, lean-hipped body emphasised by the close-fitting black T-shirt and pants he was wearing, who’d appeared out of nowhere like some mythical Dark Lord, and who was now standing in front of the statue watching her.

‘Who the hell are you?’ Shock cracked her voice. ‘And what are you doing here?’

‘How odd. I was about to ask you the same.’ A low-pitched voice, faintly husky, its drawl tinged with amusement.

‘I don’t have to answer to you.’ Realising with horror that her breasts were visible, she sank down hastily, letting the water cover everything but her head and shoulders. ‘This is private property and you’re trespassing.’

‘Then that makes two of us.’ He was smiling openly now, white teeth against the tanned skin of a thin tough face. Dark curling hair that needed cutting. A wristwatch probably made from some cheap metal and a silver belt buckle providing the only relief from all that black. ‘And I wonder which of us is the most surprised.’

It occurred to her that he looked like one of the travellers who’d been such a nuisance over the winter.