Полная версия

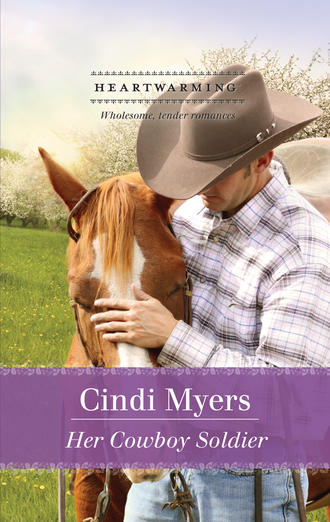

Her Cowboy Soldier

Can she open her heart?

The Hartland Herald isn’t exactly the big leagues. But for army widow Amy Marshall it’s the first step to a career that will allow her to support her young daughter and start a new life in the city. Unfortunately, writing a story that will get her noticed requires stepping on a few toes. Josh Scofield’s toes, to be exact.

Sure, her article was less than flattering. She probably shouldn’t have suggested the injured veteran got his teaching position unfairly, but a real reporter can’t pull punches. And she hadn’t pegged the former military man as someone who cared what other people thought.

As she digs deeper, though, Amy realizes there’s more to Josh than just a good story. But it will be hard to win his trust, and is there any point when she doesn’t plan on sticking around?

She clenched her hands into fists and glared at Josh.

“I’m sorry I hurt your feelings with my little article,” Amy said, “but you know what? I’m tired of you using that against me.”

She turned to walk away, but he pulled her up short, one hand on her arm. “Did you drive your husband this crazy?” he asked.

He was staring at her lips, as if measuring their fit against his own. “Y-yes,” she stuttered. “He used to say our fights kept the marriage interesting.”

“I’ll bet.” He pulled her closer, one arm encircling her waist until she was snugged against him.

“Josh?” she whispered.

“What is it?”

“I don’t think this is a good idea.”

He released her so quickly, she stumbled backward. “Go on back to the others,” he said. “I can’t think straight when you’re around.”

Clearly, neither could she. She’d been ready to kiss a man she wasn’t even sure she liked.

Dear Reader,

I love small towns. I grew up in one, and I live in one now. Close communities—whether small towns or a neighborhood in a big city—become like extended families. They can be a great source of support, or of annoyance, since it’s hard to be anonymous when everyone knows you and your business.

Hartland, Colorado, isn’t a real place, but it’s patterned after small towns I’ve known, and I think it’s the perfect location for a romantic relationship that’s aided and abetted by the extended family of friends and neighbors. My heroine, Amy, has never really known a true home, and she isn’t sure what to think about the interest the people of Hartland take in her. Josh, my hero, grew up in Hartland, but he’s not that comfortable with close scrutiny, either. These two have a lot to learn about themselves and each other, and I hope you’ll enjoy their journey.

I love to hear from my readers. You can contact me online via my website, www.CindiMyers.com, or write to me in care of Harlequin Books, 233 Broadway, Suite 1001, New York, NY 10279.

Cindi Myers

Her Cowboy Soldier

Cindi Myers

www.millsandboon.co.uk

CINDI MYERS

Cindi Myers is the author of more than fifty novels. When she’s not crafting new romance plots, she enjoys skiing, gardening, cooking, crafting and daydreaming. A lover of small-town life, she lives with her husband and two spoiled dogs in the Colorado mountains.

For Katie

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

EPILOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

AMY MARSHALL SLID a basket of tomatoes into the gap in her display and stepped back to admire the rows of gleaming produce. A banner behind the farm stand proclaimed ANDERSON ORCHARDS—FRESHEST FRUITS AND VEGETABLES. She’d toured the spice markets in Egypt and bazaars in Afghanistan, but she’d never seen a prettier sight than her own family’s produce set out for sale.

“Don’t just stand there daydreaming,” a voice behind her admonished. “See if you can find room for more squash.”

“Aye, aye, Grandma.” Amy straightened and snapped a mock salute at the trim, gray-haired woman in jeans and a sleeveless checked blouse who leaned on a metal walker. Amy’s grandmother, Bobbie Anderson, might be temporarily slowed down by hip surgery, but she still knew how to issue a command. “I’ll squash in more squash.”

“Squash the squash!” Giggling, Amy’s five-year-old daughter, Chloe, twin brown ponytails like antennae high on her head, stood on tiptoe to look over the piles of the yellow vegetable that had arrived by the bushel load from the greenhouses this morning.

“We won’t be squashing anything,” Bobbie said with mock severity. She surveyed the rows of vegetables critically. “On second thought, Amy, forget the squash for now and help with the customers. Tell Neil he can unload the truck. Chloe, come help me stack onions.”

Amy hurried to the checkout area, where retired rancher Neal Kuchek was weighing out shiny green peppers for a young couple in matching khaki shorts. “I’ll take over here,” she told him. “Grandma wants you to unload the truck.”

“Does she, now? That woman just loves to order me around.” But he grinned and headed toward the truck parked behind the produce stand.

Amy finished assisting the young couple and turned to the next customer in line. “May I help you?”

“Just these.” A man extended a plastic bag that contained three tomatoes toward her. But the hand that held the tomatoes wasn’t a hand, it was a steel hook. Amy’s smile faltered, and she lifted her gaze to meet that of her customer. He was a young man, near her own age, with the fine creases around his blue eyes of someone who had spent a lot of time squinting into the sun, and the close-cropped brown hair and erect posture that spoke of military training.

He met her stare with a steady look of his own. “You must be Bobbie’s granddaughter,” he said. “She told me you were coming to live with her. I was sorry to hear about your husband.”

In the week Amy had been in the little town of Hartland, Colorado, she had heard similar expressions of sympathy from almost everyone she’d met, each one heartfelt, and each one a sharp reminder that, though Brent had been killed in Iraq three years ago, the loss still hurt. “Thank you,” she murmured, looking away. “Did you know Brent?”

“No. I didn’t have that privilege. I suspect I was already back in the States, recuperating, when he was killed.” He offered his left hand—the one that wasn’t a hook. “Josh Scofield. I teach science at the high school.”

“Amy Marshall.” She shook hands, a brief touch that nevertheless sent a shiver up her spine, maybe because this injured soldier was such a tangible reminder of her late husband, who had never recovered from his own war wounds.

“Hello.” Chloe climbed onto an empty apple crate beside her mother and frowned at Josh. “Why do you have a hook instead of a hand?”

“Chloe!” Amy shushed her daughter, her face burning.

“It’s all right,” Josh said. “Kids are always curious.” He smiled at the little girl. “A hook makes carrying my groceries easier.” He demonstrated, looping the plastic bag of tomatoes over the end.

“But better not try to pick your nose,” Chloe said and giggled.

“You’re right. This broke me of that habit in no time.”

“This is my daughter, Chloe.” Amy put her hand on the girl’s shoulder. “I promise she usually has better manners.”

“Nice to meet you, Chloe.”

Suddenly shy, Chloe buried her face in her mother’s side.

Josh nodded to Amy. “Maybe I’ll see you around.”

Then he sauntered away, a tall, trim figure with a bag of tomatoes nonchalantly looped over the hook on the end of one arm.

“Was that Josh Scofield?” Bobbie joined her granddaughter and great-granddaughter by the cash register. “I hate that I missed him.”

“He was buying tomatoes with his hook,” Chloe said. She grinned, then skipped away, probably to “help” Neal, her current favorite person.

Bobbie’s attention focused on Amy. “You remember Josh, don’t you? Big baseball star when he was in high school.”

Amy shook her head. “I never met him.”

“You didn’t?”

“I was only here a few weeks in the summers—and I mostly stayed on the farm.” Those brief childhood visits had been precious to her, an oasis in her otherwise chaotic life.

“Hmmph. I tried to talk your folks into letting you live here with me full-time instead of dragging you all over the world with them, but they wouldn’t hear of it. They said you needed to experience adventure while you were still young and impressionable.” She sniffed. “I think what children need is a home they know they can always come back to.”

“And I always knew I had that with you.” Amy patted the older woman’s arm. Her parents, who managed an adventure tour company, had lived in twenty-three different places in eight countries by the time Amy graduated high school. As a girl, Amy had studied correspondence courses by lantern light in a grass hut in Zaire, made friends with native Laplanders in Greenland and visited Japanese temples with girls in kimonos. After all of that, spending a few weeks every summer in her grandmother’s apple orchard had seemed the more exotic life.

“Josh is a great guy,” Bobbie said. “He lost his hand in Iraq.”

“I figured as much. He said he didn’t know Brent.”

“No. I guess they were in different units. His family’s ranch, the Bar S, backs up to our orchards on the south.”

“But he doesn’t ranch.”

“He helps out his dad. And the school district hired him this year to teach science and coach baseball. Word is the Wildcats might have their first winning season in four years.”

“I guess I’ll find out tomorrow night,” Amy said. “Ed wants me to write about the baseball game for the paper. Apparently the high school kid who usually does it has come down with mono.” She’d never been particularly interested in sports, but the story would be one more credit to add to her portfolio. Her part-time job at the Hartland Herald wasn’t hard-core journalism, but she hoped the experience would help her land a better writing job in Denver or an even larger city when she left Hartland once Bobbie was on her feet again.

“Josh is single, you know,” Bobbie said. “Not even dating anyone.”

The overly casual way in which she shared this information didn’t fool Amy. “Are you trying to fix me up?”

“No.” She patted Amy’s hand. “I know you loved Brent, and losing him was hard. Believe me, I know.” Amy’s grandfather had passed away five years before, after forty-six years of marriage. “But you’re still young, and sooner or later you won’t want to be alone anymore. You could marry again, have more children...and you can’t blame me for thinking if you settled down with someone local it would be a good thing.”

The genuine concern behind the words touched Amy, erasing any resentment she might have harbored about her grandmother’s matchmaking. “You’re right. One day I probably will want to date again. But I’m not ready for that. Not yet.” And she certainly didn’t want to get involved with someone from Hartland. After a lifetime of traveling the world, she wasn’t ready to settle down in a sleepy little small town. She had big plans for her life.

* * *

IN THE BOTTOM of the ninth, the Wildcats were down by one. Josh paced the dugout, his cleats scraping on the concrete with each step. He didn’t have to look at the lineup card to know who was up next: Chase Wilson, a terrific third baseman who was at best a mediocre hitter. He stopped at the step leading to the field and clapped Chase on the back. “Take a deep breath and focus on making contact with the ball. No heroics, just a solid single,” he said. “I know you can do this.”

The boy nodded and, head down, strode to the plate. Josh leaned over the chain link that separated the dugout from the field and watched. How many times had he stood in this dugout over the years, before and after games, smelling the aromas of sunflower seeds and glove oil, hearing the clear, hollow sound of an aluminum bat connecting with the baseball? He’d sent his share of balls over the outfield fences, and pounded around the bases to the cheers of the hometown crowd. He’d loved the game the way some boys love cars or music or girls. He’d even dreamed of playing professionally, until a stint on a college team had taught him the difference between being a small-town star and having the kind of talent that lured big league scouts and big league contracts.

He’d have been happy playing league softball the rest of his life if an IED on a bleak roadside in Fallujah hadn’t changed everything.

Getting the chance to be around the game again, even as a coach, had been a dream come true. But as much as he loved the game, his real job was to help these boys develop and gain confidence in their abilities. None of them were likely to be pro players, but he could help them become better men. When he and his father had clashed during his own teen years, his coaches and male teachers had given him another perspective and helped him find his way. He wanted to do the same for his students.

The loud ringing of a hard leather ball against an aluminum bat jerked him from these musings, and a smile spread across his face as he watched the ball sail over the right field fence. “Chase! Chase! Chase!” the other boys shouted, and Josh took up the chant. He joined the crowd that swarmed the boy. “I knew you could do it,” he said, hugging the six-footer tightly.

“I did what you said, Coach. I just focused on the ball.” The boy grinned, dimples forming on either side of his mouth, making him look younger than his eighteen years. Then he was swept away toward the clubhouse by the rest of the team.

Josh looked at the scoreboard in left field: Hartland Wildcats 9, Delta Panthers 6. “Congratulations, Coach.” History teacher and assistant coach Zach Fremont slapped Josh on the back. “You’ve really turned this team around.”

“The kids are improving.” The baseball program had been in sad shape when Josh took over; he’d need a few years to develop a real championship squad.

“This win didn’t mean anything. We’ve already lost a chance at the playoffs.” Math teacher Rick Southerland, Josh’s other assistant, fired a baseball he’d collected from the other side of the dugout at Josh

Josh caught the ball awkwardly with his left hand, balancing it against his chest with his hook. “You can’t go from a losing record to a championship in one year,” he said. He wanted to take back the words as soon as he’d said them; he should know better than to let Rick bait him.

“You’re just a regular ray of sunshine, aren’t you?” Zach said.

Rick scowled at them both and made his way out of the dugout, across the field toward the clubhouse. “What is it with that guy?” Zach asked.

“He’s mad because the district cut his wife’s position as an elementary reading aid when they hired me.” Josh added the baseball to the duffel of gear at his feet. “He thinks I played the vet card to get my job.”

“So what if you did? We owe you something for what you did over there. It’s not like a lousy job is going to give you back your hand.” Zach added a pair of batting helmets to the duffel. “Besides, the school board didn’t hire you because they felt sorry for you. They hired you because they wanted a winning baseball team, and they needed a science teacher.”

With school districts cutting budgets all over the country, plenty of coaches and teachers with more experience than Josh were looking for work. He wasn’t naive enough to believe his position as a wounded veteran and the son of a local rancher hadn’t influenced the school board’s decision to choose him over half a dozen other candidates for the job. The knowledge didn’t sit easy with him. He’d always wanted to be judged on his accomplishments, not his circumstances or his name.

“Coach, do you have a minute to answer a few questions?”

The feminine voice made both men turn around. Josh found himself staring into the warm brown eyes of Amy Marshall. He felt again the little jolt that had hit him when he’d looked into those eyes yesterday at her grandmother’s produce stand. “Hello again,” he said.

“Where’s Cody?” Zach asked. “Not that you aren’t an improvement.” He grinned.

She ignored the compliment. “Cody’s out sick. I’m covering the game for the Herald.” She extended a mini recorder toward him. “What’s the significance of tonight’s win?”

Zach clapped Josh on the shoulder. “I’ll just leave you two alone.” He slung the strap of one of the equipment duffels over his shoulder and shambled away.

Josh focused his attention on Amy once more, and shifted into interview mode. “Some people might say this win is meaningless, since we’re already eliminated from the finals,” he said. “But I don’t look at it that way at all. The team has overcome a lot this season, and the players have worked together to improve. Every win builds their confidence and skills—things they’ll take forward with them into next season, and into life.”

“Had you ever coached baseball before you were hired to coach the Wildcats?” she asked.

The question surprised Josh, but he didn’t let it rattle him. “I hadn’t had that opportunity. But I played for many years.”

“Since you don’t have any experience coaching, to what do you attribute your success?”

He shifted from one foot to the other. What did these questions have to do with tonight’s game? The focus should be on the players, not him. “I’m working with a great group of kids,” he said. “I try to teach them what I know, but they’ve done the rest with their hard work.”

“Would you say luck had anything to do with your winning record?”

“Luck always plays a part in this game, but I give the credit to the team’s hard work.”

She punched the button to switch off the recorder. “Thanks. If I have any more questions, I’ll give you a call.”

“Don’t you want to ask anything about tonight’s game?”

“I got a copy of the official scorecard from Dirk Fischer and a nice quote from Chase Wilson, so I think I’m good. But I’ll let you know.” She turned to leave. By this time the area around the field was all but deserted, the stands and most of the parking lot emptied.

Josh followed her up the steps out of the dugout. “Let me walk you to your car,” he said.

“You don’t need to do that.”

“No, but it goes against my grain to let a woman walk off into a dark, deserted parking lot alone, so humor me.”

She looked out across the parking lot, which was indeed dark, and empty save for a few cars. “All right. Thank you.”

He followed her across the gravel-and-dirt lot to a dusty blue Subaru. She paused beside the door, keys in hand. “Thanks for seeing me to my car,” she said. “I forget sometimes how dark it can be out here, away from the city lights.”

“We see more stars here, though.” He looked up at a sky filled with sparks of light, as if some kid had spilled a whole bottle of glitter.

She tilted her head back to join him in admiring the sky. “Beautiful.”

“The stars are like this in Iraq, too, at least with the blackouts for the war.” Why had he brought up the war, a subject she probably didn’t want to discuss, considering she’d lost her husband over there? But she regarded him calmly, as if waiting for him to continue. “When I had guard duty I’d stand at my checkpoint and stare up at the sky and imagine I was back here at home,” he explained.

She tilted her head up toward the sky again. “Afghanistan has stars like this, too.”

“Your husband was in Afghanistan?”

“I was in Afghanistan, before the war. Well, he was, too. We were in the Peace Corps there. That’s how we met. When the war broke out, he wanted to help. He thought with his familiarity with the country and the language, they could use him in Afghanistan, but the army had other ideas.”

“Where did you live before you came back here?”

“Chloe and I were in Denver. Then my grandmother fell and broke her hip and I knew she needed help with the orchard. And I needed a place to pull myself together and decide what to do next.”

“This is a good place for that kind of thinking.” He’d spent plenty of hours in his cabin on his parents’ ranch trying to answer that same question.

“Is that why you’re here?” she asked. “To decide what to do next?”

He told himself it was a logical question. But he couldn’t help feeling her quiet gaze assessed him more accurately than he was used to. Amy Marshall had an air of perceptiveness that was both intriguing and unsettling. “I’m here because this is home,” he said. “The whole time I was away, all I could think of was getting back.”

Her expression grew pensive. “I lived all over the place growing up, so I never really had that kind of attachment to one spot.”

“I didn’t think I did, until I went away. After this—” he held up the hook “—I decided Hartland was where I belonged.”

She tilted her head. “Can I ask a question?”

“Anything.” He could always refuse to answer, though he doubted this woman could ask anything he wouldn’t be happy to tell her. He believed in being up front with people. Losing his hand—and almost losing his life—had erased any patience he might have once had for dissembling.

“Why a hook? Don’t they make pretty realistic-looking prosthetic hands?”

“They make hands that look good, but a hook is more practical.” He opened and closed the pincer ends. He’d become adept at manipulating most items with this simple tool. “And a hook is a little more in your face.” His method of confronting his loss had been to embrace it head-on. He’d told himself denial was for cowards. “This is who I am now and I wanted it out there for everyone to see. If they don’t like it, that’s their problem.”

“Do people have a problem with it?”

“A few.” He thought of Rick, who’d told one of the city council members—who’d passed the news on to Josh—that it made the school look bad to have a “gimp” for a coach.

Time to change the subject, though. Shift the focus away from him. “Do you like writing for the paper?” he asked.

She looked pleased. “I like to write, and this gives me a chance to get a few credits to my name, and some experience. Though the subject matter isn’t always that exciting.”

“I don’t know about that. I’ve seen some of your articles. You did a good job of making a city council discussion of sewer repairs interesting.”

She laughed, a light, musical sound that transformed her expression into one of startling beauty. Her eyes held a new light and the muscles of her face relaxed and softened. A soft blush suffused her cheeks and her lips curved invitingly.

He realized he’d been staring when she looked away. “I really have to go,” she said. “Thanks for your help.”

“Anytime.” He wanted to say more—that talking with her had been the best conversation he’d had since coming home. That he liked the way her eyes crinkled at the corners when she laughed.

But the words stuck in his throat. So he let her get into her car and drive away without saying any of these things. When she was gone, he looked up at the stars again. Those stars had saved him from losing it some nights on duty—the nights after he’d lost friends or seen children die, and the nights after days of endless tension and boredom. He’d imagined himself back here, in this little corner of Colorado he’d once wanted so badly to leave.