полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 2, No. 14, December 1858

The importance of the inferior singers in making up a general chorus is not always appreciated. In an artificial musical composition, as in an oratorio or an anthem, though there is a leading part, which is commonly the air, that gives character to the whole, yet this principal part would often be a very indifferent piece of melody, if performed without its accompaniments. These accompaniments by themselves would seem still more unimportant and trifling. Yet if the composition be the work of a master, however trifling and comparatively insignificant these brief strains or snatches, they are intimately connected with the harmony of the piece, and could not be omitted without a serious derangement of the grand effect. The inferior singing-birds, on the same principle, are indispensable as aids in giving additional effect to the notes of the chief singers.

Though the Robin is the principal musician in the general orison of dawn, his notes would become tiresome, if heard without accompaniments. Nature has so arranged the harmony of this chorus, that one part shall assist another; and so exquisitely has she combined all the different voices, that the silence of any one can never fail to be immediately perceived. The low, mellow warble of the Blue-Bird seems a sort of echo to the louder voice of the Robin; and the incessant trilling or running accompaniment of the Hair-Bird, the twittering of the Swallow, and the loud and melodious piping of the Oriole, frequent and short, are sounded like the different parts of a regular band of instruments, and each performer seems to time his part as if by design. Any discordant sound, that may happen to be made in the midst of this performance, never fails to disturb the equanimity of the singers, and some minutes must elapse before they recommence their parts.

It would be difficult to draw a correct comparison between the different birds and the various instruments in an orchestra. It would be more easy to signify them by notes on the gamut. But if the Robin were supposed to represent the German flute, the Blue-Bird might be considered as the flageolet, frequently, but not incessantly, interposing a few mellow strains, the Swallow and the Hair-Bird the octave flute, and the Golden Robin the bugle, sounding occasionally a low but brief strain. The analogy could not be carried farther without losing force and correctness.

All the notes of the Blue-Bird—his call-notes, his notes of alarm, his chirp, and his song—are equally plaintive, and closely resemble each other. I am not aware that this bird ever utters a harsh note. His voice, which is one of the earliest to be heard in the spring, is associated with the early flowers and with all pleasant vernal influences. When he first arrives, he perches upon the roof of a barn or upon some still leafless tree, and pours forth his few and frequent notes with evident fervor, as if conscious of the delights that await him. These mellow notes are all the sounds he titters for several weeks, seldom chirping, crying, or scolding like other birds. His song is discontinued in the latter part of summer; but his peculiar plaintive call, consisting of a single note pensively modulated, continues all day, until the time of frost. This sound is one of the melodies of summer's decline, and reminds us, like the notes of the green nocturnal grasshopper, of the fall of the leaf, the ripened harvest, and all the melancholy pleasures of autumn.

The Blue-Bird builds his nest in hollow trees and posts, and may be encouraged to breed and multiply around our habitations, by erecting boxes for his accommodation. In whatever vicinity we may reside, whether in the clearing or in the heart of the village, if we set up a little bird-house in May, it will certainly be occupied by a Blue-Bird, unless preoccupied by a bird of some other species. There is commonly so great a demand for such accommodations among the feathered tribes, that it is not unusual to see birds of several different species contending for the possession of one box.

After the middle of August, as a new race of winged creatures awake into life, the birds, who sing of the seed-time, the flowers, and of the early summer harvests, give place to the inferior band of insect-musicians. The reed and the pipe are laid aside, and myriads of little performers have taken up the harp and the lute, and make the air resound with the clash and din of their various instruments. An anthem of rejoicing swells up from myriads of unseen harpists, who heed not the fate that awaits them, but make themselves merry in every place that is visited by sunshine or the south-wind. The golden-rod sways its beautiful nodding plumes in the borders of the fields and by the rustic roadsides; the purple gerardia is bright in the wet meadows, and the scarlet lobelia in the channels of the sunken streamlets. But the birds heed them not; for these are not the wreaths that decorate the halls of their festivities. Since the rose and the lily have faded, they have ceased to be tuneful; some, like the Bobolink, assemble in small companies, and with a melancholy chirp seem to mourn over some sad accident that has befallen them; others still congregate about their usual resorts, and seem almost like strangers in the land.

Nature provides inspiration for every sentiment that contributes to the happiness of man, as she provides sustenance for his various physical wants. But all is not gladness that elevates the soul into bliss; we may be made happy by sentiments that come not from rejoicing, even from objects that waken tender recollections of sorrow. As if Nature designed that the soul of man should find sympathy, in all its healthful moods, from the voices of her creatures, and from the sounds of inanimate objects, she has provided that all seasons should pour into his ear some pleasant intimations of heaven. In autumn, when the harvest-hymn of the day-time has ceased, at early nightfall, the green nocturnal grasshoppers commence their autumnal dirge, and fill the mind with a keen sense of the rapid passing of time. These sounds do not sadden the mind, but deepen the tone of our feelings, and prepare us for a renewal of cheerfulness, by inspiring us with the poetic sentiment of melancholy. This sombre state of the mind soon passes away, effaced by the exhilarating influence of the clear skies and invigorating breezes of autumn, and the inspiriting sounds of myriads of chirping insects that awake with the morning and make all the meadows resound with the shout of their merry voices.

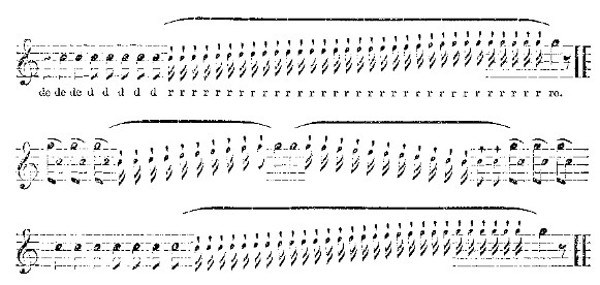

SONG OF THE WOOD-SPARROW

Note.—In the early part of the season the song ends with the first double bar; later in the season it is extended, in frequent instances, as in the notes that follow.

SONG OF THE CHEWINK

Note.—I have not been able to detect any order in the succession of these strains, though some order undoubtedly exists, and might be discovered by long-continued observation. The intervals in the above sketch cannot be given with exactness.

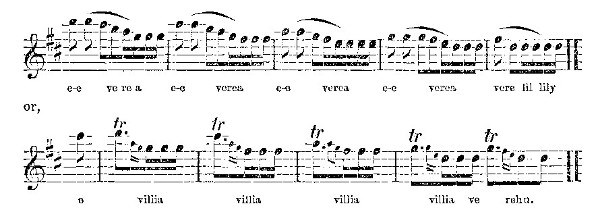

SONG OF THE VEERY

Note.—I am far from being satisfied with the above representation of the song of the Veery, in which there are certain trilling and liquid sounds that hardly admit of notation.

SONG OF THE RED MAVIS

Note.—The Red Mavis makes a short pause at the end of each bar. These pauses are irregular in time, and cannot be correctly noted.

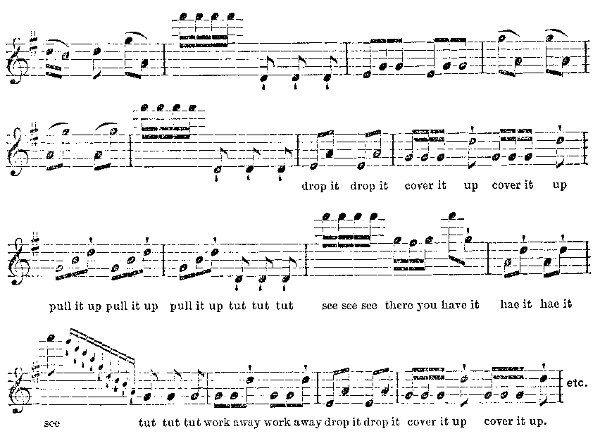

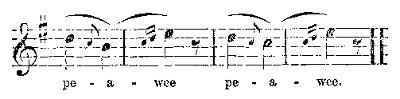

NOTE OF THE PEWEE

THE MINISTER'S WOOING

CHAPTER I

Mrs. Katy Scudder had invited Mrs. Brown, and Mrs. Jones, and Deacon Twitchel's wife to take tea with her on the afternoon of June second, a.d. 17—.

When one has a story to tell, one is always puzzled which end of it to begin at. You have a whole corps of people to introduce that you know and your reader doesn't; and one thing so presupposes another, that, whichever way you turn your patchwork, the figures still seem ill-arranged. The small item that I have given will do as well as any other to begin with, as it certainly will lead you to ask, "Pray, who was Mrs. Katy Scudder?"—and this will start me systematically on my story.

You must understand that in the then small seaport-town of Newport, at that time unconscious of its present fashion and fame, there lived nobody in those days who did not know "the Widow Scudder."

In New England settlements a custom has obtained, which is wholesome and touching, of ennobling the woman whom God has made desolate, by a sort of brevet rank which continually speaks for her as a claim on the respect and consideration of the community. The Widow Jones, or Brown, or Smith, is one of the fixed institutions of every New England village,—and doubtless the designation acts as a continual plea for one whom bereavement, like the lightning of heaven, has made sacred.

The Widow Scudder, however, was one of the sort of women who reign queens in whatever society they move in; nobody was more quoted, more deferred to, or enjoyed more unquestioned position than she. She was not rich,—a small farm, with a modest, "gambrel-roofed," one-story cottage, was her sole domain; but she was one of the much-admired class who, in the speech of New England, are said to have "faculty,"—a gift which, among that shrewd people, commands more esteem than beauty, riches, learning, or any otherworldly endowment. Faculty is Yankee for savoir faire, and the opposite virtue to shiftlessness. Faculty is the greatest virtue, and shiftlessness the greatest vice, of Yankee man and woman. To her who has faculty nothing shall be impossible. She shall scrub floors, wash, wring, bake, brew, and yet her hands shall be small and white; she shall have no perceptible income, yet always be handsomely dressed; she shall have not a servant in her house,—with a dairy to manage, hired men to feed, a boarder or two to care for, unheard-of pickling and preserving to do,—and yet you commonly see her every afternoon sitting at her shady parlor-window behind the lilacs, cool and easy, hemming muslin cap-strings, or reading the last new book. She who hath faculty is never in a hurry, never behindhand. She can always step over to distressed Mrs. Smith, whose jelly won't come,—and stop to show Mrs. Jones how she makes her pickles so green,—and be ready to watch with poor old Mrs. Simpkins, who is down with the rheumatism.

Of this genus was the Widow Scudder,—or, as the neighbors would have said of her, she that was Katy Stephens. Katy was the only daughter of a shipmaster, sailing from Newport harbor, who was wrecked off the coast one cold December night and left small fortune to his widow and only child. Katy grew up, however, a tall, straight, black-eyed girl, with eyebrows drawn true as a bow, a foot arched like a Spanish woman's, and a little hand which never saw the thing it could not do,—quick of speech, ready of wit, and, as such girls have a right to be, somewhat positive withal. Katy could harness a chaise, or row a boat; she could saddle and ride any horse in the neighborhood; she could cut any garment that ever was seen or thought of; make cake, jelly, and wine, from her earliest years, in most precocious style;—all without seeming to derange a sort of trim, well-kept air of ladyhood that sat jauntily on her.

Of course, being young and lively, she had her admirers, and some well-to-do in worldly affairs laid their lands and houses at Katy's feet; but, to the wonder of all, she would not even pick them up to look at them. People shook their heads, and wondered whom Katy Stephens expected to get, and talked about going through the wood to pick up a crooked stick,—till one day she astonished her world by marrying a man that nobody ever thought of her taking.

George Scudder was a grave, thoughtful young man,—not given to talking, and silent in the society of women, with that kind of reverential bashfulness which sometimes shows a pure, unworldly nature. How Katy came to fancy him everybody wondered,—for he never talked to her, never so much as picked up her glove when it fell, never asked her to ride or sail; in short, everybody said she must have wanted him from sheer wilfulness, because he of all the young men of the neighborhood never courted her. But Katy, having very sharp eyes, saw some things that nobody else saw. For example, you must know she discovered by mere accident that George Scudder always was looking at her, wherever she moved, though he looked away in a moment, if discovered,—and that an accidental touch of her hand or brush of her dress would send the blood into his cheek like the spirit in the tube of a thermometer; and so, as women are curious, you know, Katy amused herself with investigating the causes of these little phenomena, and, before she knew it, got her foot caught in a cobweb that held her fast, and constrained her, whether she would or no, to marry a poor man that nobody cared much for but herself.

George was, in truth, one of the sort who evidently have made some mistake in coming into this world at all, as their internal furniture is in no way suited to its general courses and currents. He was of the order of dumb poets,—most wretched when put to the grind of the hard and actual; for if he who would utter poetry stretches out his hand to a gainsaying world, he is worse off still who is possessed with the desire of living it. Especially is this the case, if he be born poor, and with a dire necessity upon him of making immediate efforts in the hard and actual. George had a helpless invalid mother to support; so, though he loved reading and silent thought above all things, he put to instant use the only convertible worldly talent he possessed, which was a mechanical genius, and shipped at sixteen as a ship-carpenter. He studied navigation in the forecastle, and found in its calm diagrams and tranquil eternal signs food for his thoughtful nature, and a refuge from the brutality and coarseness of sea-life. He had a healthful, kindly animal nature, and so his inwardness did not ferment and turn to Byronic sourness and bitterness; nor did he needlessly parade to everybody in his vicinity the great gulf which lay between him and them. He was called a good fellow,—only a little lumpish,—and as he was brave and faithful, he rose in time to be a shipmaster. But when came the business of making money, the aptitude for accumulating, George found himself distanced by many a one with not half his general powers.

What shall a man do with a sublime tier of moral faculties, when the most profitable business out of his port is the slave-trade? So it was in Newport in those days. George's first voyage was on a slaver, and he wished himself dead many a time before it was over,—and ever after would talk like a man beside himself, if the subject was named. He declared that the gold made in it was distilled from human blood, from mothers' tears, from the agonies and dying groans of gasping, suffocating men and women, and that it would scar and blister the soul of him that touched it; in short, he talked as whole-souled unpractical fellows are apt to talk about what respectable people sometimes do. Nobody had ever instructed him that a slave-ship, with a procession of expectant sharks in its wake, is a missionary institution, by which closely-packed heathens are brought over to enjoy the light of the gospel.

So, though George was acknowledged to be a good fellow, and honest as the noon-mark on the kitchen floor, he let slip so many chances of making money as seriously to compromise his reputation among thriving folks. He was wastefully generous,—insisted on treating every poor dog that came in his way, in any foreign port, as a brother,—absolutely refused to be party in cheating or deceiving the heathen on any shore, or in skin of any color,—and also took pains, as far as in him lay, to spoil any bargains which any of his subordinates founded on the ignorance or weakness of his fellow-men. So he made voyage after voyage, and gained only his wages and the reputation among his employers of an incorruptibly honest fellow.

To be sure, it was said that he carried out books in his ship, and read and studied, and wrote observations on all the countries he saw, which Parson Smith told Miss Dolly Persimmon would really do credit to a printed book; but then they never were printed, or, as Miss Dolly remarked of them, they never seemed to come to anything,—and coming to anything, as she understood it, meant standing in definite relations to bread and butter.

George never cared, however, for money. He made enough to keep his mother comfortable, and that was enough for him, till he fell in love with Katy Stephens. He looked at her through those glasses which such men carry in their souls, and she was a mortal woman no longer, but a transfigured, glorified creature,—an object of awe and wonder. He was actually afraid of her; her glove, her shoe, her needle, thread, and thimble, her bonnet-string, everything, in short, she wore or touched, became invested with a mysterious charm. He wondered at the impudence of men that could walk up and talk to her,—that could ask her to dance with such an assured air. Now he wished he were rich; he dreamed impossible chances of his coming home a millionnaire to lay unknown wealth at Katy's feet; and when Miss Persimmon, the ambulatory dress-maker of the neighborhood, in making up a new black gown for his mother, recounted how Captain Blatherem had sent Katy Stephens "'most the splendidest India shawl that ever she did see," he was ready to tear his hair at the thought of his poverty. But even in that hour of temptation he did not repent that he had refused all part and lot in the ship by which Captain Blatherem's money was made, for he knew every timber of it to be seasoned by the groans and saturated with the sweat of human agony. True love is a natural sacrament; and if ever a young man thanks God for having saved what is noble and manly in his soul, it is when he thinks of offering it to the woman he loves. Nevertheless, the India-shawl story cost him a night's rest; nor was it till Miss Persimmon had ascertained, by a private confabulation with Katy's mother, that she had indignantly rejected it, and that she treated the Captain "real ridiculous," that he began to take heart. "He ought not," he said, "to stand in her way now, when he had nothing to offer. No, he would leave Katy free to do better, if she could; he would try his luck, and if, when he came home from the next voyage, Katy was disengaged, why, then he would lay all at her feet."

And so George was going to sea with a secret shrine in his soul, at which he was to burn unsuspected incense.

But, after all, the mortal maiden whom he adored suspected this private arrangement, and contrived—as women will—to get her own key into the lock of his secret temple; because, as girls say, "she was determined to know what was there." So, one night, she met him quite accidentally on the sea-sands, struck up a little conversation, and begged him in such a pretty way to bring her a spotted shell from the South Sea like the one on his mother's mantel-piece, and looked so simple and childlike in saying it, that our young man very imprudently committed himself by remarking, that, "When people had rich friends to bring them all the world from foreign parts, he never dreamed of her wanting so trivial a thing."

Of course Katy "didn't know what he meant,—she hadn't heard of any rich friends." And then came something about Captain Blatherem; and Katy tossed her head, and said, "If anybody wanted to insult her, they might talk to her about Captain Blatherem,"—and then followed this, that, and the other till finally, as you might expect, out came all that never was to have been said; and Katy was almost frightened at the terrible earnestness of the spirit she had evoked. She tried to laugh, and ended by crying, and saying she hardly knew what; but when she came to herself in her own room at home, she found on her finger a ring of African gold that George had put there, which she did not send back like Captain Blatherem's presents.

Katy was like many intensely matter-of-fact and practical women, who have not in themselves a bit of poetry or a particle of ideality, but who yet worship these qualities in others with the homage which the Indians paid to the unknown tongue of the first whites. They are secretly weary of a certain conscious dryness of nature in themselves, and this weariness predisposes them to idolize the man who brings them this unknown gift. Naturalists say that every defect of organization has its compensation, and men of ideal natures find in the favor of women the equivalent for their disabilities among men.

Do you remember, at Niagara, a little cataract on the American side, which throws its silver sheeny veil over a cave called the Grot of Rainbows? Whoever stands on a rock in that grotto sees himself in the centre of a rainbow-circle, above, below, around. In like manner, merry, chatty, positive, busy, housewifely Katy saw herself standing in a rainbow-shrine in her lover's inner soul, and liked to see herself so. A woman, by-the-by, must be very insensible, who is not moved to come upon a higher plane of being, herself, by seeing how undoubtingly she is insphered in the heart of a good and noble man. A good man's, faith in you, fair lady, if you ever have it, will make you better and nobler even before you know it.

Katy made an excellent wife; she took home her husband's old mother and nursed her with a dutifulness and energy worthy of all praise, and made her own keen outward faculties and deft handiness a compensation for the defects in worldly estate. Nothing would make Katy's black eyes flash quicker than any reflections on her husband's want of luck in the material line. "She didn't know whose business it was, if she was satisfied. She hated these sharp, gimlet, gouging sort of men that would put a screw between body and soul for money. George had that in him that nobody understood. She would rather be his wife on bread and water than to take Captain Blatherem's house, carriages, and horse, and all,—and she might have had 'em fast enough, dear knows. She was sick of making money when she saw what sort of men could make it,"—and so on. All which talk did her infinite credit, because at bottom she did care, and was naturally as proud and ambitious a little minx as ever breathed, and was thoroughly grieved at heart at George's want of worldly success; but, like a nice little Robin Redbreast, she covered up the grave of her worldliness with the leaves of true love, and sung a "Who cares for that?" above it.

Her thrifty management of the money her husband brought her soon bought a snug little farm, and put up the little brown gambrel-roofed cottage to which we directed your attention in the first of our story. Children were born to them, and George found, in short intervals between voyages, his home an earthly paradise. Ho was still sailing, with the fond illusion, in every voyage, of making enough to remain at home,—when the yellow fever smote him under the line, and the ship returned to Newport without its captain.

George was a Christian man;—he had been one of the first to attach himself to the unpopular and unworldly ministry of the celebrated Dr. H., and to appreciate the sublime ideality and unselfishness of those teachings which then were awakening new sensations in the theological mind of New England. Katy, too, had become a professor with her husband in the same church, and his death, in the midst of life, deepened the power of her religious impressions. She became absorbed in religion, after the fashion of New England, where devotion is doctrinal, not ritual. As she grew older, her energy of character, her vigor and good judgment, caused her to be regarded as a mother in Israel; the minister boarded at her house, and it was she who was first to be consulted in all matters relating to the well-being of the church. No woman could more manfully breast a long sermon, or bring a more determined faith to the reception of a difficult doctrine. To say the truth, there lay at the bottom of her doctrinal system this stable corner-stone,—"Mr. Scudder used to believe it,—I will." And after all that is paid about independent thought, isn't the fact, that a just and good soul has thus or thus believed, a more respectable argument than many that often are adduced? If it be not, more's the pity,—since two-thirds of the faith in the world is built on no better foundation.