полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 191, June 25, 1853

Probably some of your correspondents could furnish other examples.

E. S. Taylor."Quem Deus vult perdere."—In Croker's Johnson, vol. v. p. 60., the phrase, "Quem Deus vult perdere, prius dementat," is stated to be from a Greek iambic of Euripides:

"Ὅν θεὸς θέλει ἀπολέσαι πρῶτ' ἀποφρεναι."This statement is made first by Mr. John Pitts, late Rector of Great Brickhill, Bucks1, to Mr. Richard How of Aspley, Beds, and is taken for granted successively by Boswell, Malone, and Croker. But no such Greek is, in fact, to be found in Euripides; the words conveying a like sentiment are,—

"Ὅταν δὲ Δαίμων ἀνδρὶ πορσύνῃ κακὰ,Τὸν νοῦν ἔβλαψε πρὼτον."The cause of this classical blunder of so many eminent annotators is, that these words are not to be found in the usual college and school editions of Euripides. The edition from which the above correct extract is made is in ten volumes, published at Padua in 1743-53, with an Italian translation in verse by P. Carmeli, and is to be found in vol. x. p. 268. as the 436-7th verses of the Tragedie incerte, the meaning of which he thus gives in prose "Quando vogliono gli Dei far perire alcuno, gli toglie la mente."

T.J. Buckton.Lichfield.

P.S.—In Croker's Johnson, vol. iv. p. 170., the phrase "Omnia mea mecum porto" is incorrectly quoted from Val. Max. vii. 2., instead of "Bona mea mecum porto."

White Roses.—The paragraph quoted from "an old newspaper," dated Saturday, June 15th, 1723, alludes to the commemoration of the birthday of King James VIII. (the 10th of June), which was the Monday mentioned as that before the Saturday on which the newspaper was published. All faithful adherents of the House of Stuart showed their loyalty by wearing the white rose (its distinguishing badge) on the 10th of June, when no other way was left them of declaring their devotion to the exiled family; and, from my own knowledge, I can affirm that there still exist some people who would think that day desecrated unless they wore a white rose, or, when that is not to be procured, a cockade of white ribbon, in token of their veneration for the memory of him of whose birth it is the anniversary.

L. M. M. R.Queries

"MERK LANDS" AND "URES."—NORWEGIAN ANTIQUITIES

In Shetland, at the present day, all public assessments are levied, and divisions made, according to the number of merk lands in a parish. All arable lands were anciently, under the Norwegian law, rated as merks,—a merk containing eight ures. These merks are quite indefinite as to extent. It is, indeed, clear that the ancient denomination of merk land had not reference to superficial extent of surface, but was a denomination of value alone, in which was included the proportion of the surrounding commonty or scattald. Merk lands are of different values, as sixpenny, ninepenny, twelvepenny,—a twelvepenny merk having, formerly at least, been considered equal to two sixpenny merks; and in some old deeds lands are described as thirty merks sixpenny, otherwise fifteen merks twelvepenny land. All assessments have, however, for a very long period, been levied and all privileges apportioned, according to merks, without relation to whether they were sixpenny or twelvepenny. The ancient rentals of Shetland contain about fourteen thousand merks of land; and it will be noticed that, however much the ancient inclosed land be increased by additional improvements, the number of merks ought to be, and are, stationary. The valued rent, divided according the merk lands, would make a merk land in Shetland equal to 2l. Scots of valued rent. There are only one or two places of Scotland proper where merks are in use,—Stirling and Dunfermline, I think. As these two places were the occasional residences of our ancient Scottish kings, it is possible this plan of estimating land may have obtained there, to equalise and make better understood some arrangements relating to land entered into between the kings of Norway and Scotland. Possibly some of the correspondents of "N. & Q." in the north may be able to throw some light on this subject. It was stated some time ago that Dr. Munch, Professor in the University of Christiana, had presented to the Society of Northern Archæology, in Copenhagen, a very curious manuscript which he had discovered and purchased during a voyage to the Orkneys and Shetland in 1850. The manuscript is said to be in good preservation, and the form of the characters assigns the tenth, or perhaps the ninth century as its date. It is said to contain, in the Latin tongue, several episodes of Norwegian history, relating to important facts hitherto unknown, and which throw much light on feudal tenures, holdings, superstitions, omens, &c., which have been handed down to our day, with their origin involved in obscurity, and on the darkness of the centuries that preceded the introduction of Christianity into Norway. Has this manuscript ever been printed?

Kirkwallensis.THE LEIGH PEERAGE, AND STONELEY ESTATES, WARWICKSHIRE

The fifth Lord Leigh left his estates to his sister, the Hon. Mary Leigh, for her life, and at her decease without issue to "the first and nearest of his kindred, being male, and of his name and blood," &c. On the death of Mrs. Mary Leigh in 1806, the estates were taken possession of by her very distant kinsman, the Rev. Thomas Leigh. The first person to dispute his right to them was Mr. George Smith Leigh, who claimed them as being descended from a daughter of Sir Thomas Leigh, son of the first Baron Leigh. His claim was not allowed, because he had the name of Leigh only by royal license, and not by inheritance. Subsequently, the Barony of Leigh was claimed by another Mr. George Leigh, of Lancashire, as descended from a son of the Hon. Christopher Leigh (fourth son of the aforesaid Sir Thomas Leigh), by his second wife. His claim was disallowed when heard by a committee of the House of Lords in 1828, because he could not prove the second marriage of Christopher Leigh, nor the birth of any son by such marriage.

Being about to print a genealogy of the Leigh family, I should be under an obligation to any one who will, without delay furnish me with—

1st. The descent, with dates, of the aforesaid Mr. George Smith Leigh from Sir Thomas Leigh.

2nd. The wife, and descendants to the present time, of the aforesaid Mr. George Leigh.

In return for this information I shall be happy to send my informant a copy of the genealogy when it is printed. I give you my name and address.

J. M. G.Minor Queries

Phillips Family.—Is there a family of Phillips now bearing the ancient arms of William Phillips, Lord Bardolph: viz. Quarterly, gu. and az., in the chief dexter quarter an eagle displayed or.

H. G. S.Engine-à-verge.—What is the engine-à-verge, mentioned by P. Daniel in his Hist. de la Milice Franc., and what the origin of the name?

Cape.Garrick's Funeral Epigram.—Who is the author of these verses?

"Through weeping London's crowded streets,As Garrick's funeral pass'd,Contending wits and poets stroveWhich should desert him last."Not so this world behaved to HimWho came this world to save;By solitary Joseph borneUnheeded to the grave."K. N.The Rosicrucians.—I should be extremely glad of a little information respecting "the Brethren of the Rosy Cross." Was there ever a regular fraternity of philosophers bearing this appellation; or was it given merely as a title to all students in alchemy?

I should wish to obtain a list of works which might contain a record of their studies and discoveries. I subjoin the few in my own library, which I imagine to belong to this class.

Albertus Magnus de Animalibus, libr. xxvi. fol. Venet. 1495.

Albertus Magnus de Secretis Mulierum, de Virtutibus Herbarum, Lapidum at Animalium.

Albertus Magnus de Miribilibus Mundi, item.

Michael Scotus de Secretis Naturæ, 12mo., Lugd. 1584.

Henr. Corn. Agrippa on the Vanitie of Sciences, 4to., London, 1575.

Joann. Baptist. Van Helmont, Opera Omnina, 4to., Francofurti, 1682.

Dr. Charleton, Ternary of Paradoxes, London, 1650.

Perhaps some of your correspondents will kindly furnish me with notices of other works by these writers, and by others who have written on similar subjects, as Paracelsus, &c.

E. S. Taylor.Passage in Schiller.—In the Memoirs of a Stomach, lately published, the editor asks a question of you: "Is it Schiller who says, 'The metaphysical part of love commences with the first sigh, and terminates with the first kiss'?" I pray you look to the merry and witty and learned little book, and respond to his Query.

Amicus.Sir John Vanbrugh.—This eminent architect and poet of the last century is stated by his biographers to have been "born in Cheshire." Can anybody furnish me with the place and date of his birth?

T. Hughes.Chester.

Historical Engraving.—I have an ancient engraving, size 14¾ in. wide and 11¾ in. high, without title or engraver's name, which I should be glad to authenticate. It appears to represent Charles II. at the Hague in 1660.

The foreground is occupied by groups of figures in the costume of the period. In the distance is seen a street in perspective, down which the royal carriage is proceeding, drawn by six horses. On one side is a row of horses, on the other an avenue of trees. To the right of this is a canal, on the bank of which a battery of seven guns is firing a salute. The opposite bank is occupied by public buildings.

In the air a figure of Fame holds a shield charged with the royal arms of England, surrounded by a garter, without the motto. Five cherubs in various positions are dispersed around, holding respectively a globe, a laurel crown, palm branches, &c., and a crowned shield bearing a lion rampant, and a second with a stork, whose beak holds a serpent.

A portion of the zodiacal circle, containing Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius, marks, I suppose, the month in which the event took place.

E. S. Taylor.Hall-close, Silverstone, Northamptonshire.—Adjoining the church-yard is a greensward field called "Hall-close," which is more likely to be the site of the mansion visited by the early kings of England, when hunting in Whittlebury Forest, than the one mentioned by Bridles in his History of the county. About 1798, whilst digging here, a fire-place containing ashes was discovered; also many large wrought freestones.

The well, close by, still retains the name of Hall-well; and there are other things in the immediate vicinity which favour the supposition; but can an extract from an old MS., as a will, deed, indenture, &c., be supplied to confirm it?

H. T. Wake.Stepney.

Junius's Letters to Wilkes.—Where are the original letters addressed by Junius to Mr. Wilkes? The editor of the Grenville Papers says, "It is uncertain in whose custody the letters now remain, many unsuccessful attempts having been recently made to ascertain the place of their deposit."

D. G.The Reformer's Elm.—What was the origin of the name of "The Reformer's Elm?" Where and what was it?

C. M. T.Oare.

How to take Paint off old Oak.—Can any of your correspondents inform me of some way to take paint off old oak?

F. M. Middleton.Minor Queries with Answers

Cadenus and Vanessa.—What author is referred to in the lines in Swift's "Cadenus and Vanessa,"—

"He proves as sure as God's in Gloster,That Moses was a grand impostor;That all his miracles were tricks," &c.?W. Fraser.Tor-Mohun.

[These lines occur in the Dean's verses "On the Death of Dr. Swift," and refer to Thomas Woolston, the celebrated heterodox divine, who, as stated in a note quoted in Scott's edition, "for want of bread hath, in several treatises, in the most blasphemous manner, attempted to turn our Saviour's miracles in ridicule."]

Boom.—Is there an English verb active to boom, and what is the precise meaning of it? Sir Walter Scott uses the participle:

"The bittern booming from the sedgy shallow." Lady of the Lake, canto i. 31.Vogel.[Richardson defines Boom, v., applied as bumble by Chaucer, and bump by Dryden, to the noise of the bittern, and quotes from Cotton's Night's Quatrains,—

"Philomel chants it whilst it bleeds,The bittern booms it in the reeds," &c.]"A Letter to a Member of Parliament."—Who was the author of A Letter to a Member of Parliament, occasioned by A Letter to a Convocation Man: W. Rogers, London, 1697?

W. Fraser.Tor-Mohun.

[Attributed to Mr. Wright, a gentleman of the Bar, who maintains the same opinions with Dr. Wake.]

Ancient Chessmen.—I should be glad to learn, through the medium of "N. & Q.," some particulars relative to the sixty-four chessmen and fourteen draughtsmen, made of walrus tusk, found in the Isle of Lewis in Scotland, and now in case 94. Mediæval Collection of the British Museum?

Hornoway.[See Archæologia, vol. xxiv. p. 203., for a valuable article, entitled "Historical Remarks on the introduction of the Game of Chess into Europe, and on the ancient Chessmen discovered in the Isle of Lewis, by Frederick Madden, Esq., F.R.S., in a Letter addressed to Henry Ellis, Esq., F.R.S., Secretary."]

Guthryisms.—In a work entitled Select Trials at the Old Bailey is an account of the trial and execution of Robert Hallam, for murder, in the year 1731. Narrating the execution of the criminal, and mentioning some papers which he had prepared, the writer says: "We will not tire the reader's patience with transcribing these prayers, in which we can see nothing more than commonplace phrases and unmeaning Guthryisms." What is the meaning of this last word, and to whom does it refer?

S. S. S.[James Guthrie was chaplain of Newgate in 1731; and the phrase Guthryisms, we conjecture, agrees in common parlance with a later saying, that of "stuffing Cotton in the prisoner's ears."]

Replies

CORRESPONDENCE OF CRANMER AND CALVIN

(Vol. vii., p. 501.)The question put by C. D., respecting the existence of letters said to have passed between Archbishop Cranmer and Calvin, and to exist in print at Geneva, upon the seeming sanction given by our liturgy to the belief that baptism confers regeneration, is a revival of an inquiry made by several persons about ten years ago. It then induced M. Merle d'Aubigné to make the search of which C. D. has heard; and the result of that search was given in a communication from the Protestant historian to the editor of the Record, bearing date April 22, 1843.

I have that communication before me, as a cutting from the Record; but have not preserved the date of the number in which it appeared2, though likely to be soon after its receipt by the editor. Merle d'Aubigné says, in his letter, that both the printed and manuscript correspondence of Calvin, in the public library of Geneva, had been examined in vain by himself, and by Professor Diodati the librarian, for any such topic; but he declares himself disposed to believe that the assertion, respecting which C. D. inquires, arose from the following passage in a letter from Calvin to the English primate:

"Sic correctæ sunt externæ superstitiones, ut residui maneant innumeri surculi, qui assidue pullulent. Imo ex corruptelis papatus audio relictum esse congeriem, quæ non obscuret modo, sed propemodum obruat purum et genuinum Dei cultum."

Part of this letter, but with important omissions, had been published by Dean Jenkyns in 1833. (Cranmer's Remains, vol. i. p. 347.) M. d'Aubigné's communication gave the whole of it; and it ought to have appeared in the Parker Society volume of original letters relative to the English Reformation. That volume contains one of Calvin's letters to the Protector Somerset; but omits another, of which Merle d'Aubigné's communication supplied a portion, containing this important sentence:

"Quod ad formulam precum et rituum ecclesiasticorum, valde probo ut certa illa extet, a qua pastoribus discedere in functione sua non liceat, tam ut consulatur quorumdam simplicitati et imperitiæ, quam ut certius ita constet omnium inter se ecclesiarum consensus."

Another portion of a letter from Calvin, communicated by D'Aubigné, is headed in the Record "Cnoxo et gregalibus, S. D.;" but seems to be the one cited in the Parker Society, vol. ii. of Letters, pp. 755-6, notes 941, as a letter to Richard Cox and others; so that Cnoxo should have been Coxo.

The same valuable communication farther contained the letter of Cranmer inviting Calvin to unite with Melancthon and Bullinger in forming arrangements for holding a Protestant synod in some safe place; meaning in England, as he states more expressly to Melancthon. This letter, however, had been printed entire by Dean Jenkyns, vol. i. p. 346.; and it is given, with an English translation, in the Parker Society edition of Cranmer's Works as Letter ccxcvii., p. 431. It is important, as proving that Heylyn stated what was untrue, Eccles. Restaur., p. 65.; where he has said, "Calvin had offered his assistance to Archbishop Cranmer. But the archbishop knew the man, and refused his offer." Instead of such an offer, Calvin replied courteously and affectionately to Cranmer's invitation; but says, "Tenuitatem meam facturam spero, ut mihi parcatur … Mihi utinam par studii ardori suppeteret facultas." This reply, the longest letter in their correspondence, is printed in the note attached to Cranmer's letter (Park. Soc., as above, p. 432.; and a translation of it in Park. Soc. Original Letters, vol. ii. p. 711.: and there are extracts from it in Jenkyns, p. 346., n.p.). D'Aubigné gave it entire; but has placed both Calvin's letters to the archbishop before the latter's epistle to him, to which they both refer.

Henry Walter."POPULUS VULT DECIPI."

(Vol. vii., p. 572.)If Mr. Temple will turn to p. 141. of Mathias Prideaux's Easy and Compendious Introduction for reading all Sorts of Histories, 6th edit., Oxford, 1682, small 4to., he will find his Query thus answered:

"It was this Pope's [Paul IV.] Legate, Cardinal Carafa, that gave this blessing to the devout Parisians, Quandoquidem populus decipi vult, decipiatur. Inasmuch as this people will be deceived, let them be deceived."

This book of Prideaux's is full of mottoes, of which I shall give a few instances. Of Frederick Barbarosa "his saying was, Qui nescit dissimulare, nescit imperare:" of Justinian "His word was, Summum jus, summa injuria—The rigour of the law may prove injurious to conscience:" of Theodosius II. "His motto was, Tempori parendum—We must fit us (as far as it may be done with a good conscience) to the time wherein we live, with Christian prudence:" of Nerva "His motto sums up his excellencies, Mens bona regnum possidet—My mind to me a kingdom is:" of Richard Cœur de Lion, "The motto of Dieu et mon droit is attributed to him; ascribing the victory he had at Gisors against the French, not to himself, but to God and His might."

Eirionnach.Cardinal Carafa seems to have been the author of the above memorable dictum. Dr. John Prideaux thus alludes to the circumstance:

"Cardinalis (ut ferunt) quidam μετὰ πολλῆς φαντασίας Lutetiam aliquando ingrediens, cum instant importunius turbæ ut benedictionem impertiret: Quandoquidem (inquit) hic populus vult decipi, decipiatur in nomine Diaboli."—Lectiones Novem, p. 54.: Oxoniæ, 1625, 4to.

I must also quote from Dr. Jackson:

"Do all the learned of that religion in heart approve that commonly reported saying of Leo X., 'Quantum profuit nobis fabula Christi,' and yet resolve (as Cardinal Carafa did, Quoniam populus iste vult decipi, decipiatur) to puzzle the people in their credulity?"—Works, vol. i. p. 585.: Lond. 1673, fol.

The margin directs me to the following passage in Thuanus:

"Inde Carafa Lutetiam regni metropolim tanquam Pontificis legatus solita pompa ingreditur, ubi cum signum crucis, ut fit, ederet, verborum, quæ proferri mos est, loco, ferunt eum, ut erat securo de numine animo et summus religionis derisor, occursante passim populo et in genua ad ipsius conspectum procumbente, sæpius secreta murmuratione hæc verba ingeminasse: Quandoquidem populus iste vult decipi, decipiatur."—Histor., lib. xvii., ad ann. 1556, vol. i. p. 521.: Genevæ, 1626, fol.

Robert Gibbings.LATIN—LATINER

(Vol. vii., p. 423.)Latin was likewise used for the language or song of birds:

"E cantino gli angelliCiascuno in suo Latino." Dante, canzone i."This faire kinges doughter Canace,That on hire finger bare the queinte ring,Thurgh which she understood wel every thingThat any foule may in his leden sain,And coude answere him in his leden again,Hath understonden what this faucon seyd."Chaucer, The Squieres Tale, 10746.Chaucer, it will be observed, uses the Anglo-Saxon form of the word. Leden was employed by the Anglo-Saxons in the sense of language generally, as well as to express the Latin tongue.

In the German version of Sir Tristram, Latin is also used for the song of birds, and is so explained by Ziemann:

"Latin, Latein; für jede fremde eigenthümliche Sprache, selbst für den Vogelgesang. Tristan und Isolt, 17365."—Ziemann, Mittelhochdeutsches Wörterbuch.

Spenser, who was a great imitator of Chaucer, probably derives the word leden or ledden from him:

"Thereto he was expert in prophecies,And could the ledden of the gods unfold." The Faerie Queene, book iv. ch. xi. st. 19."And those that do to Cynthia expoundThe ledden of straunge languages in charge." Colin Clout, 744.In the last passage, perhaps, meaning, knowledge, best expresses the sense. Ledden may have been one of the words which led Ben Jonson to charge Spenser with "affecting the ancients." However, I find it employed by one of his cotemporaries, Fairfax:

"With party-colour'd plumes and purple bill,A wond'rous bird among the rest there flew,That in plain speech sung love-lays loud and shrill,Her leden was like human language true."Fairfax's Tasso, book xvi. st. 13.The expression lede, in lede, which so often occurs in Sir Tristram, may also have arisen from the Anglo-Saxon form of the word Latin. Sir W. Scott, in his Glossary, explains it: "Lede, in lede. In language, an expletive, synonymous to I tell you." The following are a few of the passages in which it is found:

"Monestow neuer in ledeNought lain."—Fytte i. st. 60."In lede is nought to layn,He set him by his side."—Fytte i. st. 65."Bothe busked that night,To Beliagog in lede."—Fytte iii. st. 59.It is not necessary to descant on thieves' Latin, dog-Latin, Latin de Cuisine, &c.; but I should be glad to learn when dog-Latin first appeared in our language.

E. M. B.Lincoln.

JACK

(Vol. vii., p. 326.)The list of Jacks supplied by your correspondent John Jackson is amusing and curious. A few additions towards a complete collection may not be altogether unacceptable or unworthy of notice.

Supple (usually pronounced souple) Jack, a flexible cane; Jack by the hedge, a plant (Erysimum cordifolium); the jacks of a harpsichord; jack, an engine to raise ponderous bodies (Bailey); Jack, the male of birds of sport (Ditto); Jack of Dover, a joint twice dressed (Ditto, from Chaucer); jack pan, used by barbers (Ditto); jack, a frame used by sawyers. I have also noted Jack-Latin, Jack-a-nod, but cannot give their authority or meaning.

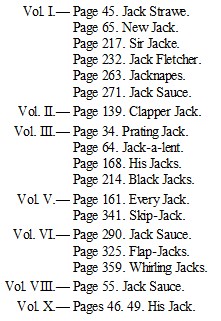

The term was very familiar to our older writers. The following to Dodsley's Collection of old Plays (1st edition, 1744) may assist in explaining its use:

Your correspondent is perhaps aware that Dr. Johnson is disposed to consider the derivation from John to be an error, and rather refers the word to the common usage of the French word Jacques (James). His conjecture seems probable, from many of its applications in this language. Jacques, a jacket, is decidedly French; Jacques de mailles equally so; and the word Jacquerie embraces all the catalogue of virtues and vices which we connect with our Jack.