Полная версия

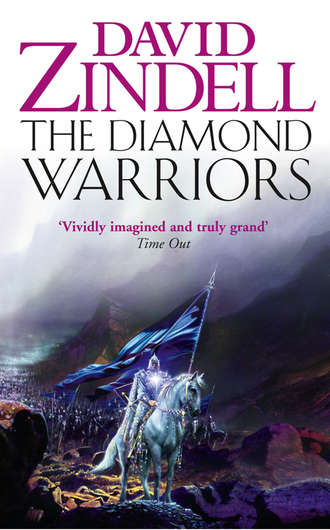

The Diamond Warriors

‘He fell before the Great Battle,’ Lord Noldashan told me. ‘If that is the right word. For in truth, Morjin’s men crucified him.’

Many standing in the hall knew the story that Lord Noldashan now told me: that when Morjin’s army had invaded and laid waste the Lake Country, Lord Noldashan’s two sons had been out on a hunting trip in the mountains to the north. After waiting as long as he could for them to come home, Lord Noldashan finally rode off to join the gathering of the warriors. But Televar and Sar Jonavar had never received my father’s call to arms. They returned to find that Morjin’s army had swept through the Lake Country, and that Morjin’s men were about to burn their farm to the ground. The two brothers then fell mad. In the ensuing battle, Morjin’s soldiers captured both of them – along with Lord Noldashan’s wife and two daughters. They crucified all of them, and left them for the vultures. Two days later, after Morjin’s army had moved on, a neighbor had found Lord Noldashan’s family nailed to crosses. Miraculously, Sar Jonavar still lived. The neighbor then summoned help to pull Sar Jonavar down from his cross and tend his wounds until Lord Noldashan could return.

As Lord Noldashan finished recounting this terrible story, his raspy voice choked up almost to a whisper. I did not know what to say to him. I did not want to look at him just then.

‘Once they called you the Maitreya,’ he said to me. ‘But can you bring back the dead? Can you keep my remaining son from joining the rest of my family?’

He doubts, I thought, feeling my heart moving inside me like a frightened rabbit, because I doubt – and that is the curse of the valarda. But how can I not doubt?

How could I, I wondered, ever defeat Morjin if I first must accomplish an impossible thing? The most dreadful thing in all the world that I could not quite bring myself to see?

I finally managed to make myself face Lord Noldashan. In the anguish filling up his moist, black eyes, I saw my own life. Then a brightness blazed within me again. In truth, it had never gone out. I remembered how, in Hesperu, in the most terrible of moments, Bemossed had clasped my hand in his and looked deep inside me as if he could behold the brightest light in all the universe.

‘You have spoken of the dead,’ I said to Lord Noldashan. ‘And we have walked with the dead, you and I.’

I looked around at the hall’s stone walls, hung with banners and shields and the heads of various animals that Lord Avijan and his family had hunted: lions, boars and elks with great racks of antlers spreading out like the limbs of a tree. Above an arch of one of the corridors giving out onto the hall, Lord Avijan had mounted the head of a white bear. It looked exactly like the beast whose will Morjin had seized and sent to murder Maram, Master Juwain and me in the pass between Mount Korukel and Mount Raaskel: the great ghul of a bear that I had killed with my old sword.

‘There are the dead, and there are the truly dead,’ I told Lord Noldashan. ‘When Morjin would have turned me into a ghul, the man I call the Maitreya gave me his hand and pulled me back into life. There, I found my mother and grandmother – my brothers, too. And my father, the King.’

I stepped over to him and his son, and I felt his whole being wincing inside even as his back stiffened and he stared at me.

‘So long as we don’t forget,’ I said to him, ‘so long as we live, truly and deeply, with passion, they cannot really die. And neither can we.’

I laid my hand on the gauntlet covering Sar Jonavar’s hand, and eased it off. A circle of reddish scar marred the back of his hand and his palm, which seemed slightly misshapen, as if the bones had been pushed apart. I grasped his hand then, gently, and I felt something warm and bright pass from me into him, and from him into me. He looked at me with tears in his eyes as he said, ‘My apologies for not fighting with you at the Commons. The greatest battle of our time, and I missed it.’

Then I removed his other gauntlet so that he wouldn’t have to hide his shame, which was really no shame at all.

‘Sometimes,’ I said to him, ‘the greatest battle is just to go on living.’

At this, he clasped his other hand around my arm and smiled at me.

I felt the blaze that burned inside me grow even brighter. I looked at the men gathered around me: Lord Harsha, Lord Avijan, Lord Sharad, Sar Jessu and Sar Shivalad and all the others. And they looked at me.

They are afraid, I thought. The greatest warriors in the world, and they are afraid.

I could feel how their dread of Morjin tormented their very bodies and souls. And then, for the first time in my life, I opened my heart to these grave men whom I had always revered. I moved over to Lord Sharad and set my hand upon his chest, where I could feel the hurt of his old wound where an Ishkan lance had once pierced him. I touched Sar Viku Aradam’s shoulder, which I sensed must have been split open, perhaps by an axe or a sword. And then on to grasp the stump below Vishtar Atanu’s elbow and rest my hand on Araj Kharashan’s mangled jaw. And so it went as I walked around the hall to honor other warriors and knights, Sar Barshan and Sar Vikan and Siraj Evar, touching my hand to heads and arms and faces and nearly every other part of a man’s body that could be torn or cut or crushed.

I drew strength from my friends, looking on: from Liljana, who had gazed into the horror of Morjin’s mind, and now could not smile; from Estrella, who could not speak; from Maram, who had been burned to a blackened, oozing crisp in the hell of the Red Desert. And from Atara, who could not look at me with her eyes, but somehow communicated all her wild joy of life despite the most terrible of mutilations.

Then my fear suddenly went away. I knew with an utter certainty of blood and breath that I had something to give these warriors who had come here to honor me. The light inside me flared so hot and brilliant that my heart hurt, and I could not hold it. I did not want to hold it within anymore, but only to pass it on, through my hand as I pressed it against the side of Sar Yardru’s wounded neck, and through my eyes as I looked into old Sar Jurald’s eyes, still haunted by the deaths of his sons at the Culhadosh Commons. And with this splendid light came the promise of brotherhood: that we would never fail each other and would fight side by side to the end of all battles. And that there was no wound or anguish so great that we could not help each other to bear it. And most of all, that we would always remind each other where we had come from and who we were meant to be.

That was the miracle of the valarda: how my love for these noble warriors could pass from me like a flame and set afire something bright and inextinguishable in them. At last, I returned to where Lord Noldashan stood, staring at me. I pressed my hand to his, and felt it come alive with an incendiary heat.

‘I am sorry,’ I told him, ‘for your family.’

For a long time he stood looking at me as if wondering if he could bring himself to say anything. His eyes seemed like bright black jewels melting in the light of some impossibly bright sun. Finally, he seemed to come to a decision, and his breath rasped out: ‘And I am sorry for yours. I should not have said what I said. You are not to blame for what Morjin did to our land. In truth, it is as Sar Jessu has told, that without you, the battle would have been lost. I know this in my heart.’

I squeezed his hand, hard, and held on tightly to keep myself from weeping. I did not succeed. Through the blur of water filling my eyes, I saw Lord Noldashan gazing at me with a terrible, sweet sadness, and so it was with Lord Harsha and Lord Avijan and many others. But within them, too, burned a great dream.

‘You are not to blame for Morjin’s deeds,’ Lord Avijan affirmed, inclining his head to me. ‘As for your own deeds, we shall honor them in the telling and retelling, down to our grandchildren’s grandchildren – and beyond, when our descendants know of Morjin only by the tale of how we Valari vanquished him, leaving to legend only his evil name.’

Sar Vikan then came forward and said to Lord Noldashan, ‘Well, sir, I am certainly to blame for what I said to you. I wish I could unsay it. But I since I cannot, I will ask your forgiveness.’

‘And that you shall have,’ Lord Noldashan said, clasping his hand. ‘As I hope I shall have yours for forgetting that we are brothers in arms.’

At this, Lord Harsha called out his approval, and so did Sar Jessu and dozens of other warriors.

Then Lord Noldashan turned back to me as he laid his arm around Sar Jonavar’s shoulders. ‘Despite my misgivings, I came here tonight because my son has great hope for you. And because I loved your father and Lord Asaru. An oath, too, I gave to Lord Avijan, but he has released me from it. What, then, should I now do?’

‘Only what you must do,’ I told him.

Lord Noldashan continued gazing into my eyes, and then said, ‘My head speaks one thing to me, and my heart another. It is the right of a warrior to stand for one who would be king – or not to stand. But once this one is king, no one may gainsay him.’

I felt something vast and deep move inside Lord Noldashan. Then he glanced at Lord Sharad, before looking back to me and smiling grimly. ‘Very well, then, Lord Elahad, I will follow you past the very end of the earth, to the stars or hell, if that is our fate.’

As he bowed deeply to me, a hundred warriors drummed the hilts of their swords against the tables. Then Lord Avijan stepped forward, and held up his hand. He called for fresh pots of beer to be brought up from his cellar. When everyone’s cup had been filled anew, he raised his cup and cried out: ‘To Lord Valashu Elahad, heir of the Elahads, Guardian of the Lightstone, and the next king of Mesh!’

I sipped my thick, black beer, and I found it sweet and bitter and good. I smiled as Alphanderry came forth and everyone hailed this strange minstrel. Tomorrow, I thought, we must meet in council again to lay our plans for my gaining my father’s throne – and for Morjin’s eventual defeat. But now we had a few moments for camaraderie and cups clinked together, and singing songs of glory and hope far into the night.

4

In that time of year when the wild asparagus growing along the hillsides and roads reached its peak and the lilacs laid their sweet perfume upon fields and gardens, the call for warriors who would support my claim to Mesh’s throne – and perhaps much more – went out into every part of the land. They came to Lord Avijan’s castle, in twos and threes, and sometimes tens and twenties, riding up in full diamond armor and bearing the bright emblems of their families. Most of them lived in the country near the Valley of the Swans and Mount Eluru, but many also arrived from the north, in the mountains near the two Raaswash rivers, and from the southern highlands below Lake Waskaw. Fewer hailed from the hills around Godhra, for there Lord Tanu held sway, as did Lord Tomavar in the Sawash River valley and its three largest cities: Pushku, Lashku and Antu. But a warrior had the right to give his oath to whom he wished, and at least ten men from Pushku had braved Lord Tomavar’s anger by rallying for me. And fifty-two men – led by the long-faced Lord Manthanu – had journeyed all the way from Mount Tarkel above the Diamond River in the far northwest.

Soon the number of warriors overflowing the grounds of Lord Avijan’s castle had swelled to more than one thousand. Lord Avijan’s stewards worried about finding food for this growing army. But as the Valley of the Swans between Silvassu and Lake Waskaw held some of Mesh’s richest farmland, to say nothing of woods full of deer, it seemed that no hour passed without a few wagons full of barley, beef and salted pork rolling up through the pass between Mount Eluru and the sparkling lake below it.

My companions and I kept busy during this period of waiting. While Master Juwain and Liljana tried to further the children’s education, contending with each other as to exactly which subjects they should teach Daj and Estrella, and how, I greeted the arriving warriors one by one. The most distinguished of them joined Lord Avijan, Lord Harsha and other great knights in taking council where we discussed the strengths and weaknesses of Lord Tanu and Lord Tomavar. Although I asked Maram to attend these meetings, he insisted on attending to the matter of exploring the capaciousness of Lord Avijan’s beer cellars. As he put it, ‘These countrymen of yours drink like an army of parched bulls, and I’d at least like a little taste of beer before it’s all gone.’

Although Master Juwain had practically given up lecturing him about the evils of strong drink, Liljana kept scolding him whenever she had the chance. On the third day of our stay at Lord Avijan’s castle, she took Maram aside and said to him, ‘We all know that bad times are coming. You should spend your days helping Val, as we all try to do – either that or learning more about your firestone.’

Now that Bemossed kept Morjin from using the Lightstone, or so we prayed, those of us possessing gelstei found ourselves free to discover new depths and powers of these ancient crystals.

‘Bad times are coming,’ Maram said to Liljana, ‘and that is exactly the point. The only way to fight the bad is with the good, and right now I can think of nothing better than to fortify myself against the evils of the future with some good Meshian beer.’

He might have added that beautiful young women would have served best of all to drive back his fears, but in the overcrowded castle he never knew when Lord Harsha might come around the corner of some cold stone corridor and take him to task for mocking his professed love for Behira.

Of all of us, I thought, Atara had the hardest work with her gelstei, for the kristei’s deepest virtue was said to be not merely the seeing of the future but its creation. But how could a single woman, through the force of her will alone, contend with Morjin’s great fury to destroy all who defied him, to say nothing of his master, Angra Mainyu?

At one of our councils, after she had told Lord Manthanu of her grandfather, Sajagax’s, strategy to persuade a few Sarni tribes to oppose Morjin, Lord Manthanu asked her to give the assembled warriors a good omen. They had talked that evening of cutting apart Morjin’s best knights with their fearsome kalamas, and their spirits were running high. Atara did not wish to discourage these brave men, but neither would she speak anything but the truth. And so, in her scryer’s way, she told them: ‘Then it will be as you wish, and your swords will cleave the armor of even the best knights of Morjin’s Dragon Guard.’

She did not, however, reveal how many of them might live to fulfill this gruesome prophecy, and they could not bring themselves to ask her.

But it is not the way of fortune to progress in one direction forever: the cresting wave crashes into sand even as day passes into night. On the seventh of Soldru, after a long day of hunting, sword practice, councils and feasting on roasted venison, I retired to the rooms that Lord Avijan had appointed for me in the southern corner of the keep. They gave out into a small garden full of herbs, roses and bushes heavy with lilac blossoms. I sat on one of the stone benches there to listen to the crickets chirping and watch the stars come out. It was the only place in Lord Avijan’s castle where I could find a space of solitude and listen to the whisperings of my soul.

Some time before midnight, with the moon waxing all silvery and full, Liljana found me there walking along the lilac hedges. Although she had brought me some tea, I could tell at once that serving me a soothing drink had little to do with the purpose of her visit. As she set out the pot and cups on one of the tables near the garden’s great sundial, I could almost feel her willing her hand not to tremble. Even so the cups rattled against the hard stone with such force that it seemed they might break.

‘What is wrong?’ I asked her, taking her by her arm and urging her to sit down with me.

‘Does there have to be anything wrong,’ she said, ‘for me to bring you a little fresh chamomile tea?’

‘No, of course not,’ I told her. ‘But something is troubling you, isn’t it?’

She nodded her head as she took out her gelstei. In the light of the moon, I could barely make out the blue tones of this little whale-shaped figurine. And then she said to me, ‘I have terrible tidings.’

Something in her voice pierced me like an icy wind.

‘What tidings?’ I asked her. Without thinking, I grabbed hold of her arm. ‘Are the children all right? Is Master Juwain?’

‘They are fine,’ she told me, ‘but –’

‘Is it Kane, then? Has word come of his death?’

It did not seem possible, I thought, that this invincible warrior who had survived countless wars in every corner of the world over thousands of years had finally gone back to the stars. Nor did I wish to believe that Maram, in a drunken stupor, had stumbled down the stairs after exiting some young woman’s bedchamber and broken his neck. Most of all, I could not bring myself to think of any violence harming even a single hair of Atara’s head.

‘No, we’re all safe here tonight,’ Liljana said to me. ‘But others, in places that we had thought were safe, are not. Or so I think.’

Her round, pretty face could hide a great deal when she wished, and she could hold herself calm and careful even when delivering the most disastrous of news. Such was her training as the Materix of the Maitriche Telu. It occurred to me for the thousandth time how glad I was to have this wise and relentless woman as my companion and not my enemy.

I sat on my hard stone seat breathing deeply and waiting for her to say more. I looked around at the roses and lilacs of the starlit garden for sign of the Ahrim – and then back at Liljana to see if she might tell me that this terrible thing had gained some dreadful new power. I reminded myself that if I would rule over Mesh, I must first and always rule myself.

‘I came to tell you tidings,’ she said to me again as she rotated her little figurine between her fingers, ‘but I cannot tell you with absolute certainty that these tidings are true.’

‘You speak more mysteriously,’ I told her, ‘than does a scryer.’

She would have laughed at this, I thought, if she had been able to laugh. Instead she said to me, ‘Perhaps I should have just spoken of what I know, with my very first breath, but I wanted to prepare you first. I don’t want you to give up hope.’

My heart seemed to be having trouble pushing my blood through my veins. Finally I said to her, ‘Just tell me, then.’

‘All right,’ she said, drawing in a deep breath. ‘I believe that the Brotherhood school has been destroyed.’

I gazed straight at her, trying to make out the black centers of her eyes. I felt as bereft of speech as Estrella.

‘It would have happened around the end of Ashte,’ she told me.

I continued gazing at her, then I finally found the will to say: ‘You mean the Brotherhood school of the Seven, don’t you? But no place in the world is safer! Morjin could not have found it!’

I thought of the magic tunnels through the mountains surrounding the Valley of the Sun, and I shook my head.

‘But he has found it,’ she told me as she covered my hand with hers. ‘Somehow, he has.’

‘But the Seven, and those that came before them, have kept the school a secret for thousands of years. And Bemossed has had scarcely half a year of sanctuary there. How could Morjin suddenly have found it?’

The answer, I thought, was built into the very words of my question. Bemossed, contending with Morjin for mastery of the Lightstone over a distance of a few hundred miles, touching upon the very filth of Morjin’s soul, must somehow have drawn down Morjin upon him.

‘Is he dead, then?’ I asked Liljana. ‘Have you come to tell me that Bemossed is dead?’

‘I came to tell you not to give up hope,’ she said, squeezing my hand. ‘And so if I knew the Shining One was dead, how could there be hope?’

I considered this for a moment as I looked at her. ‘But you cannot tell me that he is not dead.’

She sighed as she held up her crystal to the lanterns’ light. ‘I cannot tell you very much for certain at all.’

She went on to say more about her personal quest to explore the mysteries of her blue gelstei and gain mastery over it. In the Age of the Mother, she told me, in the great years, the whole continent of Ea had been knitted together by women in every land speaking mind to mind through the power of the blue gelstei. The Order of Brothers and Sisters of the Earth had trained certain sensitive people to attune to the lapis-like crystals, cast into the form of amulets, pendants, pins and figurines. Some had gained the virtue of detecting falseness or veracity in others’ words, and these were called truthsayers. Others found themselves able to speak in strange languages or remember events that had occurred long before their birth or give others great and beautiful dreams. Only the rarest and most adept in the ways of pure consciousness, however, learned to hear the whisperings and thoughts of another’s mind. No one knew why those most talented at mindspeaking had always been women. With the breaking of the Order into the Brotherhood and that secret group of women that became the Maitriche Telu, men had almost completely lost knowledge of the blue gelstei while any woman possessing even a hint of the ability to listen to another’s thoughts was reviled as a witch.

‘I know that the time is coming,’ Liljana said to me, ‘when the whole world will be one as it was in the Age of the Mother. We will make it so: those who still keep the blue gelstei or have the will to try to attune themselves to one, whether they hold the sacred blestei in hand, or not. I have not spoken to you of this, but I have been trying to seek out these women. If we could pass important communications from city to city and land to land at the speed of thought, we would gain a great advantage over Morjin.’

I nodded my head at this, then said, ‘Assuming that he himself does not have this power.’

‘He is a man,’ she huffed out with a wave of her hand as if that said everything.

‘He is a man,’ I said, ‘who somehow managed to control his three droghuls’ every thought and motion from a thousand miles away.’

‘Yes, droghuls,’ she said. ‘Creatures made from his own mind and flesh.’

‘Kane,’ I said to her, ‘believes that Morjin keeps a blue gelstei.’

‘Even if he does, and is able to project his filthy illusions through it, that does not mean that he can speak mind to mind with other men.’

Some deep tension in her throat made me look at her more closely as I said to her, ‘Only men dwelled at the Brotherhood’s school. How, then, did you come by your knowledge of its destruction?’

‘It was Master Storr,’ she told me. ‘I believe he kept a blestei.’

I remembered very well the Brotherhood’s Master Galastei: a stout, old man with fair, liver-spotted skin and wispy white hair. A suspicious man, who spent his life in ferreting out secrets, whether of men and women or ancient crystals forged ages ago.

‘I was casting my thoughts in that direction,’ she continued. ‘I know I touched minds with him – it was only an hour ago! When the full moon rises and the world dreams, that is the best time to try to speak with others far away. Somewhere to the west, on the Wendrush, I think, the moon rose over Abrasax and Master Storr – perhaps the other Masters as well. And, I pray, over Bemossed. They were fleeing.’

She went on to explain that she had only had a moment to make out all that Master Storr wanted to tell her.

‘Somehow Morjin must have learned the secret of the tunnels,’ she said, ‘for he sent a company of Red Knights through one of them – right down through the valley. There was a battle, I think. A slaughter The younger brothers tried to stand before the Red Knights while the Seven escaped.’