Полная версия

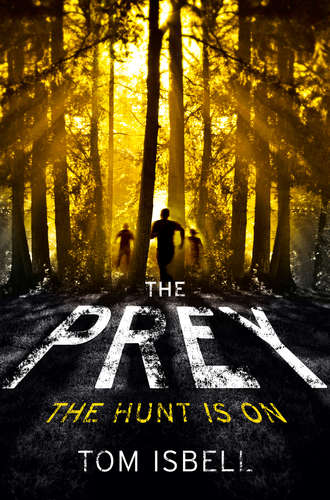

The Prey

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Tom Isbell 2015

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Johnnyhetfield/Getty Images (people); Shutterstock.com (trees).

Tom Isbell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007528189

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007528172

Version: 2015-01-20

Dedication

To Pat and Pam,

Sisters

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Liberty

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part Two: Escape

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Part Three: Prey

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE

LIBERTY

Wild animals never kill for sport. Man is the only one to whom the torture and death of his fellow creatures is amusing in itself.

—JAMES ANTHONY FROUDE

from Oceana, or, England and Her Colonies

PROLOGUE

Blood drips from fingertips, splashing the floor. A mosaic of white hexagons, outlined in black, now splotched with red. Droplets, then a puddle, a pond, a lake.

Blood. Purpling. Coagulating before his eyes.

Darkness presses against the outer reaches of his periphery, narrowing his vision. The world grows dim.

He reaches out a hand against the blood-smeared wall. Fingers squealing on tiles. Tries to call for help but the words get strangled in his throat. He collapses to the floor.

Eyes land on a knife, its razor edge trimmed in red. Blood. His blood.

Darkness closing in. The world reduced to a pinprick. Fatigue washes over him like a summer storm.

My final moments, he realizes. All come down to this.

He does not hear the door swing open, the swift stomping of feet. The ripping of fabric. The improvised tourniquet. Being lifted and carried, swept out the door, leaving behind a world of black and white and red.

1.

WE FOUND HIS BODY on a Sunday morning. Three circling buzzards, their black silhouettes etched against a blazing blue sky, clued us in that something might be down there. Down in the gullies where the foothills gave over to desert.

At the very edge of the No Water.

We thought a possum. Perhaps even a wolf. Certainly not a kid fried like an egg, stretched out in the meager shade of a mesquite bush.

He wasn’t dead, but if we hadn’t found him when we did, he would’ve been. Maybe within the hour. Then this story never would’ve happened. There’d be nothing to write about because it all changed that late-spring morning, the day we found him dying of dehydration at the edge of the desert.

He was sandy-haired, about our age, lying spread-eagled on the ground like a giant X. Red ran back to camp to tell the officers, while Flush and I turned him over. The sun had burned his face to a crisp, cracked his lips, swollen his eyes shut. Dried sweat stains marked his black T-shirt and jeans, and, oddly, he was barefoot. Barefoot in the desert! Blisters big as quarters, caked with dirt and blood, dotted the undersides of his feet.

We poured water from our canteens into his mouth. Some of it made it to his throat; the rest dribbled down his neck, carving trails in his dust-covered face.

The camp Humvees came hurtling across the dunes. The boy stirred, his eyes opening into a squint.

“He’s alive!” Flush shouted. Master of the obvious.

He mumbled something neither of us could quite make out. I bent down, stretching my gimp leg out to the side so I could press my ear close to his mouth.

“What was that?” I asked.

I gave him another slurp of water. He tried to speak, the sounds painful to listen to. Like stepping on broken glass, all crunch and scrape.

Red jumped from the Humvee, Major Karsten right behind.

“Th-th-there,” Red said, with his tendency to stutter.

“Stand back,” Karsten said. No one didn’t obey an order from Major Karsten.

Wearing desert camouflage, he marched across the sandy terrain, his boots leaving massive footprints in the earth. He knelt by the boy’s side, picked up his right arm, and examined it. There was a thick burn mark there: a ridge of red scar tissue oozing pus. Karsten inspected it a full twenty seconds before feeling for a pulse. By then, other vehicles had arrived, disgorging brown-shirted soldiers.

“Get him to the infirmary,” Karsten commanded.

The soldiers loaded the boy onto a stretcher and slid him into the Humvee like a pan of dough going into an oven. The vehicle roared back to camp.

“Who found him?”

Major Karsten was looking right at us, his anvil-shaped face skeletal in appearance. The sun cast a deep shadow on the scar that angled from left eyebrow to chin.

“We all did,” Flush said.

“Ever seen him before?”

“No, sir.”

“Did he say anything?”

Flush was about to answer but I beat him to it. “He tried. Nothing came out.”

Karsten’s eyes settled on me. I knew that gaze. Feared that gaze.

“Nothing?” Karsten asked.

“No, sir,” I answered.

His eyes narrowed as though gauging whether I was being truthful or not. “Come see me when you get back, Book. I want a full report. You LTs return to camp,” he said over his shoulder. “That’s enough CC for one day.”

Black smoke belched from the exhaust and the remaining Humvees made doughnuts in the desert before ascending the ridge.

“I saw him first,” Flush said, his pale, round body sinking in the shifting sand as he and Red plodded up the hill ahead of me. “Why didn’t Karsten ask me for a report? Why Book?”

“Do you want to m-meet with Karsten?” Red asked.

“Well, no,” Flush conceded.

“Then shut your p-piehole.”

That’s the way it was—people talking about me as if I wasn’t even there. Sometimes I felt utterly invisible. Like if I turned around and took a suicide walk into the No Water, no one would notice. I guess that’s why I buried myself in books. There was comfort there. Security.

As the heat seeped through the soles of my shoes, a sense of dread settled in my stomach. The prospect of facing Major Karsten was enough to send a wave of nausea through me. Of all the officers in Camp Liberty, he was by far the most feared.

But it was more than that—I had lied. The boy had said something. Words I alone had heard. Words that raised the short hair on the back of my neck.

“You’ve gotta get me out of here,” he said, seconds before the first Humvee pulled up. And then, for good measure, he repeated it once more.

You’ve gotta get me out of here.

2.

HOPE BENDS HER EAR to the cave’s entrance, her body tense.

She’s convinced she’s hearing sounds. Not the noises she’s grown accustomed to—scurrying rats, the flap of bats’ wings—but something else entirely. A rustle of leaves? Something … human.

She fears the soldiers are getting close.

“Hope,” her sister whispers.

“Shh.”

“Hope,” Faith says again.

Hope motions her sister to be quiet … and then sees the reason for her distress. Lying on black bedrock, their father’s head lolls listlessly from side to side. Hope leaves the mouth of the cave and hurries to his side. In flickering candlelight, she sees his cheeks are badly sunken, his normally robust face pale as chalk. When she places a hand on his forehead, it’s scalding.

“He’s burning up,” Hope says. She turns and sees the tears welling in her sister’s eyes. Hope points to a small pool farther back in the cave. “Go soak a rag and we’ll place it on his forehead.”

“What rag? We don’t have anything.” Faith’s voice borders on panic.

While it annoys Hope that Faith can’t solve problems on her own, she’s right about this: they don’t have a thing. The last few weeks have been a desperate scramble from one hiding place to another. They’ve been forced to leave nearly all their possessions behind, burying them in remote patches of the wilderness. They’ll have no need of them once they reach the Brown Forest and cross into the new territory.

If they reach the Brown Forest.

Hope rips the bottom off her shirt and hands the filthy wad to Faith. “Here. Now go.”

Faith scuttles to the cavern’s dark recesses.

Hope takes her father’s hand. It’s rough and callused, more like sandpaper than skin. She studies his left foot, now nearly twice as big as his right. It’s purple and inflamed, with red lines shooting up the calf. All because he stepped on a jutting nail, its tip scarred with rust and radiation. After all they’ve been through, to have it come down to something as simple as a little infection.

Which has grown into a big infection.

She stares at the cave’s entrance, still not sure if she heard something. Drifting clouds obscure what little moon there is.

A voice startles her.

“Go easy … on your sister.” Her father, his words gravelly.

Hope grows suddenly defensive. “I do.”

Her father grunts. “She tries, you know.”

“Yeah, well, sometimes not hard enough.”

He forces a smile, the wrinkles creasing beard stubble. A corner of his black mustache angles up. “Sounds like my words.”

Of course they’re his words. Where else would she have learned them?

His eyes close. Then he whispers, “You’re your father’s daughter. And she’s … her mother’s daughter.”

It’s true, of course—no denying it—and it always strikes Hope as odd that two siblings, born mere minutes apart, can be so utterly different. It’s obvious that she and Faith are twins. Both sport matching black hair, identical brown eyes, the same tea-colored skin. The only physical difference is weight; Faith is perilously thin … and getting more so by the day.

But in all other respects they are wildly different. Faith is shy, introverted, afraid to take chances, while Hope is just the opposite: fearless, athletic, bold to the point of reckless. As far as Hope’s concerned, they may as well have sprung from separate mothers entirely.

Hope remembers the day they raced sticks in the stream behind the house. What were they then, five or six? Although it was obvious Faith would rather have been inside attending to her dolls, she agreed to play, and they ended up shouting with delight, rooting for their tiny twigs tumbling down the mountain creek.

But when the soldiers showed up and the sound of bullets echoed off the surrounding hills, Hope and Faith forgot racing sticks. Forgot how to smile and laugh. The girls’ last memory of that childhood home—and their childhood itself—was their mother lying dead, blood pooling from her forehead onto the warped boards of the front porch.

Hope dragged her sister to a hollow log and there they stayed for two whole days. When their father returned from a hunting trip, the three of them took off, not even daring to return home to bury their mother or pack supplies. They feared the Republic’s soldiers were staking out the house.

That was ten years ago. They’ve been on the run ever since, rifling through abandoned houses, living in trees and caves. They even spent one winter in a grizzly’s den, praying the bear wouldn’t return.

Out of necessity, Hope has grown more tomboyish with each passing day, learning how to start fires, how best to throw a spear. Her only vanity is her hair, which is black and long and silky—resembling her mother’s. A way of honoring her fallen parent.

“One thing,” her father says. “You have a choice to make.”

Hope stares down at him. What’s he talking about? “All we’ve been doing these last ten years is making choices,” she says.

“This one’s different.” His voice is a raspy whisper. “There’s a reason the government’s after us.”

“Yeah, because you didn’t sign the loyalty oath.”

He gives his head a shake. “That’s just part of it.”

What is he about to tell her? And why does she feel a sudden dread?

“Go on,” she says.

“You’re twins.”

Hope sighs in relief. “Gee, I had no idea.”

He continues, “And the government wants twins.”

Hope cocks her head. Where’s her father going with this? Is he delirious with fever or is this for real? “I don’t get it. What’s so special about twins?”

He grimaces. “You have a choice to make. Either stay together … which means you’ll be hunted the rest of your life …”

“Or what?” she dares to ask. She realizes she has ceased to breathe.

“Or separate.”

His words are like a thunderclap. Separate? It’s true, Faith can be irritatingly slow and often holds them up. But separate? The thought has never crossed her mind.

She peers toward the cave’s interior; Faith is wringing water from the rag. Her skeletal silhouette looks ghostlike. Draped around her shoulders is their mother’s pink shawl. It’s tattered and torn, singed from fire.

“Why would we do that?” Hope asks her father. “Faith wouldn’t last a day.”

“If they catch you … neither of you will.”

Hope wants desperately to find out what on earth he’s talking about—but at that moment Faith returns. She places the damp cloth on her father’s forehead. His eyes close and he’s asleep within seconds.

“What was he saying?” Faith asks.

“Nothing,” Hope answers a little too quickly. “Just nonsense. Fever and all.”

Hope crawls back to the cave’s entrance, staring into the dark through a curtain of dripping snowmelt. Her father’s words bounce around her head. Separate from Faith? Abandon her? What an absurd idea.

As the black night presses against her, Hope can only pray it’s a decision she’ll never have to make.

3.

I TYPED UP MY report using one of the camp’s bulky typewriters. Although we’d heard of cell phones and computers and something called the internet, all that was fried by the electromagnetic pulse that accompanied the bombs.

Omega, they called that day. The end of the end.

One enormous burst of electromagnetic radiation and everything that was even remotely electronic was fried to a crisp. Computers became the stuff of legend. Most cars were no longer drivable. And although I’d read about them, I’d never seen an airplane in the sky. And figured I never would.

Not that Camp Liberty was without luxuries. Every Friday night we gathered in the mess hall to watch movies, the film projector powered by the camp’s generators. The problem was, only a handful of movies survived, all oldies, and so we saw the same ten films all year, every year. Stagecoach, Shane, To Kill a Mockingbird, that kind of thing.

I stripped the paper from the typewriter’s roller. For obvious reasons, I neglected to mention the boy’s whispered message. I walked the report over to Major Karsten’s office and left it with Sergeant Dekker.

“Slice slice,” he said with a sneer, enjoying the in-joke that—thankfully—only a couple of us understood.

My face burned and I got out of there as fast as I could.

Days passed. Rumors flew. Some claimed the boy in the black T-shirt was a convict on the run. Others said he was no outlaw, merely an LT from an adjoining territory.

What I couldn’t figure out was why he was in the middle of the No Water in the first place, on the outskirts of an orphanage.

That’s what Camp Liberty was, although in official Republic jargon it was called a “resettlement camp.” There were several hundred of us, all guys, most with birth defects brought on by Omega’s radiation. Those toxic clouds remained floating above the earth like Christmas ribbon encircling a present, just waiting for someone to tighten the bow.

Our poor mothers had been doused with so many gamma rays or alpha particles or whatever it was, that they brought us into the world with one too many fingers or one too few or shriveled arms. Or, in my case, one leg shorter than the other. And then they died shortly after giving birth.

It was never clear how it all began. Some say a group of no-goods on the other side of the planet got hold of weapons of the nuclear kind. Others claim our own allies were to blame, attacking countries who then counterattacked. However it started, a dozen nations ended up shooting off nuclear warheads like it was the Fourth of July, until every major city in the world was obliterated. Utterly wiped out.

Of course, since all this took place a good twenty years ago, we had to rely on what the soldiers told us. Which wasn’t always accurate.

It was the other camps I wondered about. They had to be out there, right? There were rumors, of course—grisly tales of torture and atrocities—but who really knew what was true and what was made up.

“John L-183?” A Brown Shirt was standing by my table in the mess hall.

“Yeah?”

“The colonel wants to see you.”

My fork lowered. Whenever Colonel Westbrook asked to see an LT, it usually meant one thing: punishment. Was it the false report? Had the colonel somehow figured out the boy had told me more than I let on?

“Maybe you’re going through the Rite early,” Flush suggested. I shook away the notion. No one graduated until they were seventeen. I still had another year.

“That’ll teach you to read so many books,” Dozer said, snorting. He was a barrel-chested LT who could never be accused of reading books.

The acne-scarred soldier waited for me to get up. Like all the soldiers in camp, he wore a uniform of black jackboots, dark pants, and a brown shirt. That’s why we called them Brown Shirts. We were clever that way.

I left the mess hall feeling like I was headed to my execution. Sunlight blinded me as we crossed the camp’s infield. Above us, the flag atop the pole cracked in the wind like a whip. Snap. Snap.

We approached the headquarters, an ancient, rotting log building that sat in the middle of camp like a festering sore. An older Brown Shirt sat hunched over a sheaf of papers, a sweaty sheen covering his face.

Three straight-backed chairs lined the wall. To my surprise, one of them was occupied. It was the boy from the No Water.

Even though I’d helped save the guy’s life, he didn’t offer a word of thanks. Didn’t even acknowledge my presence.

The door to an inner office opened and out stepped Colonel Westbrook. He was of medium height with an unimposing face, his dark brown hair styled in a kind of comb-over across his skull. Like all the officers, he wore a dark badge on his left sleeve. It sported the Republic’s symbol: three inverted triangles.

I must’ve seen the colonel a thousand times, but never up close. For the first time I noticed the blackness of his eyes. There was not a bit of color in them at all. My heart was in my throat as I followed him to his office.

There were two others in the room as well. Sergeant Dekker, wearing his customary smirk beneath his oily hair, and Major Karsten, sitting ramrod straight by the window. Perspiration trickled down my side.

Westbrook’s eyes focused on a manila folder opened before him. His finger traced one line of information after another. “You’re John L-183,” he said at last. “The one they call Book, yes?” He said my name as though it was something unpleasant tasting.

“That’s right.”

“Nothing to be ashamed of. We need more scholars. They’re the future of the Republic.” His tracing finger halted, and I knew exactly where he’d gotten to in my life history. Blood rushed to my face.

“Liberty has a new member,” he said, his coal-black eyes boring into me. “We want you to show him around. Any problem with that?”

“Um, no, sir.”

“Get him situated. The sooner he’s one of us, the better for all concerned.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, relieved. This wasn’t a punishment after all.

“And, Book?” Colonel Westbrook leaned in, his fingers splayed on the desk like talons. “See what you can find out. Where’s he from? He’s got no marker and we don’t know much about him. After all, if he’s in need of help we have to know what he’s been through. You can understand that, can’t you?” A pointed reference to my own past.

“Yes, sir,” I said. “But I don’t want to rat on people.”

“It wouldn’t be ratting. It’d be informing.” He smiled grimly. “It’s very simple, Book. You help us, we help you. And who knows? A year from now, when you go through the Rite, we might look into making you an officer.”