полная версия

полная версияThe Nursery, No. 109, January, 1876, Vol. XIX.

Various

The Nursery, No. 109, January, 1876, Vol. XIX. / A Monthly Magazine for Youngest Readers

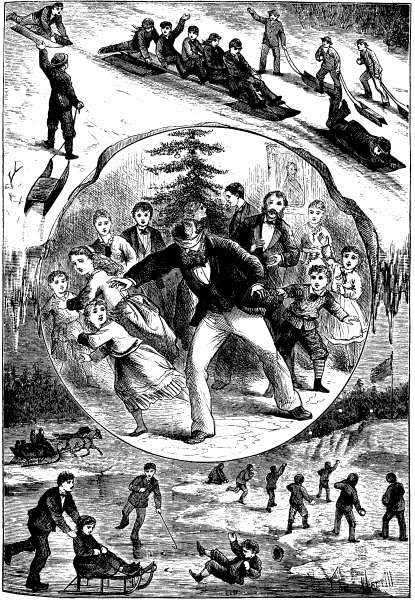

CHRISTMAS AT THE NORTH

CHRISTMAS AT THE NORTH.

Hark! the bells are sounding;Christmas draweth nigh;Now let joy aboundingBid all trouble fly.Ye who pine in sorrow,Come, be cheered to-day;Of our gladness borrow,As you freely may.First give your attentionTo our Christmas-tree;But pray do not mentionAll the things you see:These are for surprisesTo the children dear,—To the Anns, Elizas,Johnnys, Charleys here.Are you hale and hearty,And still young enough?Come, then, join our party,And play blind man's buff.But if with the coastersYou would rather be,See them there, the boasters!Join them: you are free.Hark! the sleigh-bells tinkle:Do you wish a ride?Will it smooth a wrinkleJust to have a slide?See, the road invites you;See, the ponds entice:Take, then, what delights you:Whether snow or ice.If the path to gloryBest your mood befits,If you'd live in story,And can brave hard hits,See, where heroes yonderStorm the fort with balls;Do not stop to ponder:Go where glory calls!Or, perhaps, the skatersNow attract you most:We are patient waiters—Will you skate, or coast?Do not fear a tumble;See poor Tommy there!Up, without a grumble,He will never care.Welcome to our pleasuresAnd our Christmas cheer!We'll not stint the measures:Would you all were here!Boys and girls together,—From all parts and climes,To enjoy this weather,And these Christmas times!Alfred Selwyn.

POMPEY GUARDING BABY

My real name is Pompey; but Mr. John sometimes calls me Pompous. What he means by that I do not know. Perhaps it is a joke. Mr. John is the eldest brother of Dot, the baby.

I am put here to keep watch over Dot. That is a picture of me as I appear seated on a chair by the side of the cradle where Dot is sleeping.

I am very fond of babies. One reason of it, I think, is, that they cannot hurt me with their little hands. They pull my ears, but not so hard as to give me pain.

Once, on a hot day, when my mouth was open, and my tongue was out, Dot took hold of my tongue, and pulled it as hard as he could. I did not even say Bow-wow. I let him pull away.

I would have all people know that this baby is not to be touched while I am here. If you come near to disturb baby, I shall bark; but, if you try to touch him, I shall bite. So be careful. You must not even touch baby's rattle that lies on the floor.

I hear my mistress tell people what a good dog I am, and how she can trust me to take care of baby. Yes, I am proud to say I do my duty. I hold my head up, and keep my eyes wide open. That drawing of me is from a photograph, and is a very good likeness. As I can't write, I have got Master John to write this down for me.

Master John.THE PARROT FEEDING ITS YOUNG

The parrot is a curious bird. Here is a picture of one feeding its young. It has a large hooked beak, and climbs trees by the aid of its beak and feet.

The plumage of parrots varies in color. I have seen it of a bright green, also, red and gray. These birds were well known to the ancient Greeks and Romans, who got them mostly from India and Africa.

The parrot, as every child knows, can be taught to talk. This power it shares with some other birds whose tongues are thick, round, and almost the same in form as that of the parrot. Starlings, blackbirds, jays, jackdaws, and ravens can imitate the human voice.

The parrot imitates all the noises it hears—the mewing of cats, the barking of dogs, and the cries of birds—as easily as it imitates speech. The parrots brought from Africa seem to prefer imitating the voices of children, and, on that account, more easily receive their education from them.

But the gray parrot imitates the grave tones of older persons. A parrot from Guinea, taught on the voyage by an old sailor, had caught up his hoarse voice and cough perfectly. Afterwards, owned and taught by a young girl, it did not forget the lessons of its first master. It was amusing to hear this bird pass from a soft, girlish voice to his hoarse and sailor-like tone.

Not only has the parrot the power of imitating the human voice, but it seems to wish to do so. This is shown by its attention in listening, and by the efforts it makes to repeat every word. It will often repeat words or sounds that no one has taken the trouble to teach it.

A parrot which had grown old with its master, and shared with him the pains of old age, being used to hear but little more than the words, "I am very ill," when asked, "What is the matter, Polly?" answered in a dismal tone, and stretching itself, "I am very ill."

The language of the parrot is not wanting in ideas. When you ask one if it has breakfasted, it knows well how to answer you, if it has satisfied its hunger. It will not tell you that it has breakfasted when this is not the case: at least, you cannot force it to say "No" when it ought to say "Yes."

I have heard of a parrot, which, when pleased, would laugh most heartily, and then cry out, "Don't make me laugh so! I shall die, I shall die." The bird would also mimic sobbing, and exclaim, "So bad, so bad! got such a cold!" If any one happened to cough, the parrot would remark, "What a bad cold!"

Uncle Charles.

The Sea-Swallow.

LITTLE RUTH'S PRAYER

ARTHUR'S MISHAP

I am a little boy, three years old, named Arthur; and I want to tell you what happened to me last summer.

I went down to the seashore to visit my grandmamma, alone, without mamma, or Mary, my nurse. Grandpapa took me in the cars, and I staid almost a week. I had a good time; for they have horses and cows and pigs and chickens, and a swing.

One day, Aunt Anna and I went to the duck-pond. I had a rod and line, and made believe fish. Aunt Anna turned away for a minute, and, when she looked around, all she could see of me was my hat, floating on the water. I had tumbled in, and was way down at the bottom of the pond.

But I soon rose to the top; and Aunt Anna reached over, and pulled me out, and ran up to the house with me in her arms. I did not cry at all, but coughed and sputtered a little, and told her I didn't like that old duck-pond.

Grandmamma took off all my wet clothes, and wrapped me in a blanket, and sang me to sleep. When I waked up, I felt all right. I got a good drink of water when I was in the pond; but I don't mean to go very near the edge next time.

E. B.PUSSY GETS A WARNING

"Pussy, now that you are here, I wish to say a few words to you; and it will be for your peace of mind to give heed to them at once. I have seen you several times, of late, looking sharply at that little wren's nest in the pear-tree."

"Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow!"

"Yes, I know what you mean by that; but you need not plead innocence. You think, that, as soon as those eggs are hatched, you'll have a good feast on the little birds."

"Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow!"

"Oh, you needn't deny it. Now, old cat, take my advice, and, if you don't want to come to grief, shun temptation in season. If I find you harming those birds, do you know what will happen?"

"Mee-ow, mee-ow, mee-ow!"

"Oh, you don't, eh? Well, I'll leave it to you to guess what will happen. I'll only say this: there will be a noise at the river-side one of these fine mornings, and a certain cat may get a ducking."

"Mee-ow, mee-ow! Fitt! Fitt!"

"You object to that, do you? Then, pussy, don't let me find you meddling with the little birds or watching their nests."

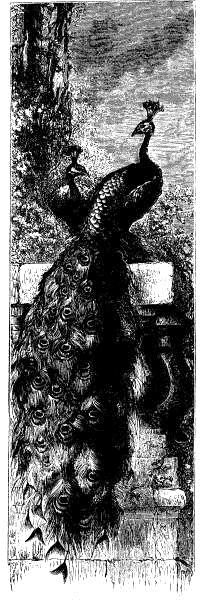

Frank."PROUD AS A PEACOCK."

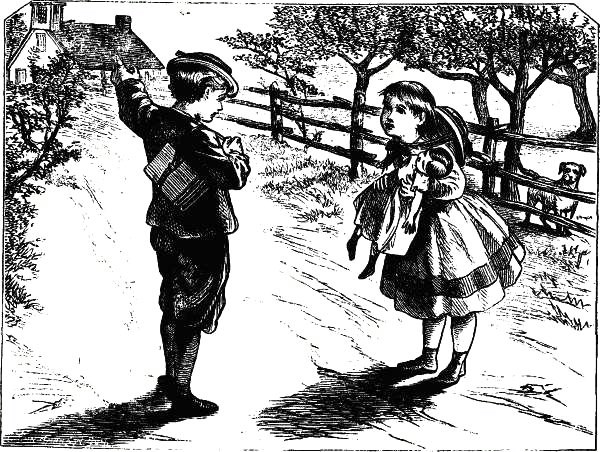

A DIALOGUE

Laura.—Why is it, Rachel, that you wear that old winter dress to church, this fine spring morning? Look at me.

Rachel.—What a pretty silk! And what a becoming hat and plume!

Laura.—I gave my mother no peace till she got them for me. Why don't you make your father buy you a new spring dress, Rachel?

Rachel.—He would have given me such a dress, if I had not told him I should like something else better.

Laura.—Indeed! Pray, what else would you like better than a beautiful spring dress?

Rachel.—I knew that if my father gave me a silk dress this spring, he could not afford to let me take music-lessons: so I told him I would rather study music than have a new dress.

Laura.—What a silly girl, to prefer music-lessons to a nice new dress!

Rachel.—Hark! What is that harsh noise?

Laura.—It is the cry of that foolish peacock from the balcony of the garden yonder. He wants us to admire him.

Rachel.—How he struts about, and arches his neck, and shows his fine feathers, bright with all the colors of the rainbow!

Laura.—I would not change my canary-bird for him.

Rachel.—And I would not change my music for your new silk dress, Laura.

Laura.—Why do you say that? But, first, who is that man standing there by the garden-gate?

Rachel.—That is Mr. Blunt, the clergyman who is to preach for us to-day.

Laura.—He looks at me, and now he looks at the peacock, and now at me again, and now, with a smile, at the peacock, and now—O Rachel! this is too bad. I know what he is thinking of.

Rachel.—Let us hurry on to church. The bell has begun to toll.

Laura.—Ah, Rachel, he says to me, as plainly as looks can say, that I am as vain as yonder peacock.

Rachel.—Why, Laura, how you blush! Do you think you deserve such a reproof?

Laura.—I do, I do. Here, this Sunday morning, I have been thinking more of my new summer silk than of any thing else. Like that screeching peacock, I have been vain of my fine feathers. Yes, let us hurry on to church. One sermon I have had already. It was all given in a look.

Rachel.—You are quick to take a hint, I see.

Laura.—I hope I may be as quick to profit by it. "Pride shall have a fall," says the proverb; and my pride has fallen.

Rachel.—I shall not try to help it up, my dear.

Anna Livingston.GRANDMOTHER'S STORY

One summer afternoon, when grandmother was sitting in her old arm-chair, just outside of the door, little Jane looked fondly up in her face, and said,—

"Tell us a story, grandma."

"A story, child!" said grandma. "Why, I never made up a story in my life."

"But you can tell a true story," said Ruth, who was seated on the doorstep,—"about something that happened when you were a little girl."

While they were talking, George and Charles and Snap, the dog, had come running up to join the group. Grandma stopped in her knitting, thought a moment, and said,—

"Well, children, sit down, all of you, and I will tell you a true story."

So the children all took seats; and grandma began:—

When I was a little girl, about the age of Ruth, my father was preceptor of the Hingham Academy. You have all been in Hingham. It is only fifteen miles from Boston. We go there now, by rail or by steamboat, in less than an hour; but, in those days, we used to go by a sailing-packet; and it was sometimes a whole day's journey.

Well, in our family there was a French boy, named Bernard Trainier. His mother was not living. His father lived in Toulon, France. At that time, France, under the great Napoleon, was continually at war, and all her young men were forced into the army. I suppose it was to save Bernard from this fate, that he was sent to America. Mr. Trainier was acquainted with a French gentleman, Mr. Duprez, who then lived in Boston; and, through him, Bernard was placed in my father's care to be educated.

Well, he was a bright, pleasant boy. He soon learned to speak English; and I and my sisters and brothers became very fond of him. He would have been very happy, but for one thing. He longed to see his little brother John, whom he had parted with at Toulon.

One day, to his great delight, Bernard received a letter from his father, telling him that John was also to be sent to America, and that he would take passage from Marseilles by the first vessel bound for Boston.

At that time there were no steamships and no regular packets from Europe. The only way of coming was by a merchant-vessel. So Bernard, who was looking and longing for the arrival of his brother, did not think it strange when six weeks passed away without bringing him. But when two months passed, and he did not appear, poor Bernard began to be anxious. Four months, five months, six months, passed. Nothing was heard of John. Not a word came from Mr. Trainier. More than a year passed away, and still there was no news. Bernard was in despair.

One August day (it must have been, I think, in the year 1805), when my father had occasion to visit Boston, he took Bernard with him; and, while there, went with him to call on Mr. Duprez, from whom they hoped to hear some good news.

But there was no comfort for poor Bernard in what Mr. Duprez had to tell. He had learned from friends in Toulon that Mr. Trainier, soon after sending his youngest son to America, had gone to St. Domingo to look after some estates. St. Domingo was then in a state of insurrection. The slaves had risen against their masters. When last heard from, Mr. Trainier had been taken prisoner, and it was feared that he had been put to death. As to John Trainier, all that could be learned was that he had been put on board a vessel bound from Marseilles to Boston, but the name of the vessel or what had become of her nobody knew.

You may imagine the distress of Bernard at hearing this, and how sad my father was when he took the poor boy's hand to return with him to Hingham. The packet station was at the head of Long Wharf. They reached it long before the vessel was ready to sail: so, to pass away the time, they walked slowly down the wharf,—my father still holding Bernard by the hand. They stopped a few minutes at the end of the wharf, then walked back again.

They had got about half way up the wharf when they heard a shout behind them. They looked around. The voice seemed to come from the water side. As they looked, a boy about eleven years old, dressed in rough sailor-clothes, jumped ashore from a brig at the wharf, and came running towards them, calling, "Bernard! Bernard!" again and again.

Bernard stood a moment as if amazed; then, suddenly letting go of my father's hand, he gave a cry of joy, sprang forward and caught the little sailor in his arms. It was his brother John.

Here grandma stopped. There was silence a few minutes. Then the questions began to come thick and fast. "Where had John been all this time?" "And why didn't he get to Boston before?"

"Well," said grandma, "I must tell that in a few words; for my story is getting long."

The captain of the brig had promised Mr. Trainier that he would see the little boy safely landed at the house of Mr. Duprez in Boston. But the captain was a bad man. Instead of treating John as a passenger, he forced him to do duty as a cabin-boy.

Then, instead of going to Boston, the brig went to New York, and from there on a long voyage to some foreign port. At last she had come to Boston; but the captain had no idea of letting John go even then. He meant to carry him away again, and would have done so but for the accidental meeting of the two brothers on Long Wharf.

"The captain had to let him go after that, didn't he, grandma?" said little Jane.

"Of course he did," said grandma. "My father soon settled that point. He took John on board the packet, and brought him to Hingham. I well remember the time when the brothers came home, and how John told the story of his hardships, and how we all cried when we heard it, and then laughed with joy to see Bernard so happy."

"And was not John happy too?" asked Ruth.

"Yes, indeed," said grandma. "And yet both the boys were sad when they thought of their father's fate, and felt that they were orphans with no means of support. We all did our best to cheer them up, and my father told them they should have a home with us till they were old enough to take care of themselves."

"And what became of them? Are they living now? Tell us all about them," said the children.

"Ah! I must save that for another story. This is enough for to-day."

Jane Oliver.

Scene on the Hudson River.

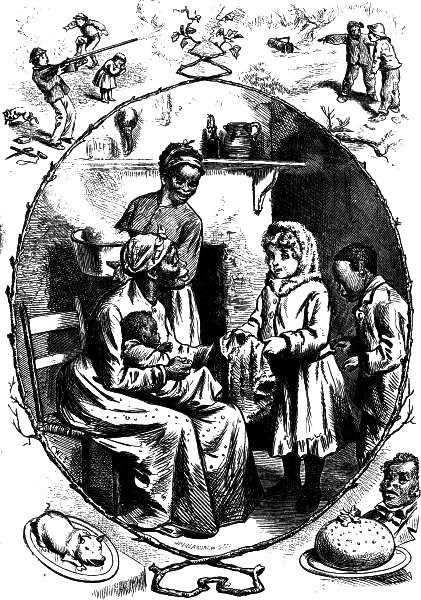

CHRISTMAS AT THE SOUTH

Christmas at the South is usually a much milder day than it is at the North. The ponds are not often frozen, and there is little or no snow on the ground: so there is no skating, or coasting, or throwing of snow-balls, or merry jingle of sleigh-bells.

But we have very good times at the South notwithstanding. The boys go out with their guns, and sometimes shoot a wild turkey; but often they shoot just for the sake of making a noise. Their traps are set, too, about this time, for squirrels, as you may see in the picture.

Games of foot-ball and base-ball are not uncommon; and I have known it mild enough for girls and boys to play croquet on the lawn, or to row in a boat on the river.

What is that little girl doing in the central part of the picture? She is making a present of a sack to her good old nurse, who now has a baby of her own. The sack is for the baby. How glad they all are—the mother, the aunt, and the little boy, who, I think, must be the baby's brother!

As for the Christmas feast at the South, it may be very much like that at the North. In the picture we get a glimpse of a roast pig and a plum pudding. There is often a wild turkey and a plenty of other game.

"But is there a Christmas-tree? And does Santa Claus come with his trinkets, and his picture-books, as at the North?" Yes, in many families there is a Christmas tree, and Santa Claus does not forget that there are little children at the South also.

In the evening, the little ones play blind-man's-bluff, or hunt-the-slipper. Sometimes Jack Frost steals down from the North, and pinches them. But he does not stay long. He likes his northern home best.

Uncle Harry.

CHRISTMAS AT THE SOUTH.

THE CHRISTMAS PRESENTS

Mr. D. had promised to give his wife a beautiful rattan rocking-chair as a Christmas present. It was his employment to sell these articles. In due time, Mrs. D. called at his place of business, and selected a chair; but, as she sat enjoying it for a few minutes, a new idea came into her mind, and she told her husband that she would gladly do without her present, if he would give Jennie and Alice (their two little daughters) each a chair.

Her husband agreed to this; and on Christmas Eve he took home with him two elegant little rocking-chairs. Leaving them in his garden, he went in to tea, and, after taking his seat at the table, said to his children, "I have a story to tell you, and it is a true story. Would you like to hear it?"

Of course they were all eager to do so. So he said, "There was a lady in my store to-day, whose husband had promised to make her a Christmas present of a rocking-chair. After she had selected a very nice one, she turned to her husband, and said, 'If you will give each of our children a chair, I will forego the pleasure of having mine.' Now, wasn't she truly kind?"

The children were much interested in the story; and both exclaimed, "Yes, sir!" Then he added, "I liked the lady very much."

Here, little Alice, growing slightly jealous, exclaimed, "Did you like her better than you do mamma?"

"Oh, no! not better, but full as well," answered her father.

After supper, the chairs were brought in, much to the surprise and delight of Jennie and Alice, who both joyfully exclaimed, "O papa! you meant us!"

D.THE PROPER TIME

OUR DOG MILO

Milo was the name of a fine Spanish pointer. He had such an expressive face, such delicate ears, and such wise eyes, that you could not help looking at him.

And then he could stand up so cleverly on his hind-legs, dressed in his little red coat and cap! An old beggar-woman, whose eyesight was not very good, once took him for a boy, and thanked the "little man," as she called him, for a present which we boys had trained him to go through the form of offering.

He had belonged to a travelling company of jugglers and rope-dancers, by whom he had been taught various tricks, though he had been made to undergo much hard treatment. He could fire off a pistol, stand on guard as a sentinel, beat a drum, and serve as a horse for the monkeys of the show.

This last piece of work poor Milo did not at all like. The monkeys would scratch and plague him; and, if he resented it, he would be whipped. His worst enemy was a little monkey named Jocko, who delighted to torment him.

At last, we boys talked so much to our good papa about Milo, that he bought him of the jugglers. How happy we were when we got possession of him! Poor Milo seemed to be aware of our kind act. After that, it seemed as if he could not do too much to show his gratitude.

How patiently he would stand on his legs, or march with us in our mimic ranks as a soldier, when we went forth to battle! In all our plays we could not do without Milo. He would stand on guard beside our camp; and he it was who always had to fire the pistol when a deserter was to be shot.