полная версия

полная версияThe Buffalo Runners: A Tale of the Red River Plains

Indeed the whole party would have probably been killed and the settlers massacred at that time, but for the courageous interposition of the chief of the half-breeds, Cuthbert Grant, who, at the risk of his life, stood between the settlers and their foes, only one of which last was killed.

When old McKay and his party drew near to the scene, the massacre was completed, and most of his little band—which had been slightly augmented on the way up—turned right-about, and rode away to defend their respective homes.

But the warrior spirit of old McKay and his sons had been roused. They refused to turn tail, and, in company with Dan and Peter Davidson, made a furious charge into a detached party of the half-breeds which they chanced to encounter. They scattered them like sheep, though they did not succeed in killing any. Then they also wheeled round and galloped back to their respective homes.

“Come, Elspie, tear,” said the old man as he dismounted, “putt what ye value most in your pocket an’ come away. The duvles are down on us, and we are not able to hold out in Ben Nevis. The settlers must choin altogether, an’ do the best we can to defend ourselves.”

While he was speaking, the Highlander was busy stuffing some of the smaller of his household goods into his pockets—amongst them a large quantity of tobacco.

Meanwhile Fergus hastened to the stable to saddle Vixen for Elspie, while the poor girl ran to her room and secured some small objects which she valued—among them a miniature portrait of her mother, and a Bible which the good lady had given to her a short time before her death. There was no money, and no valuable documents had to be looked after, so that preparations for fight were soon completed.

Now there was a member of old Duncan McKay’s household who has not yet been introduced to the reader, but whose character and influence in the household were such as to demand special notice. This member was an old woman named Peg. Probably this was an abbreviation of Peggy, but we cannot tell. Neither can we say what her surname was, for we never heard it, and no one spoke of the old creature by any other name than that of “Old Peg.”

Although Old Peg was by no means feeble—indeed, judged by her capacities, she might have been pronounced middle-aged, for she could walk about the house all day, actively engaged in miscellaneous self-imposed duties, and could also eat like a man and sleep like a dormouse—she was, nevertheless, withered, and wrinkled, and grey, and small. Her exact age nobody knew—and, for the matter of that, nobody seemed to care.

Extreme amiability and self-obliteration were the chief characteristics of Old Peg. She was silent by nature, and deaf as a post—whether by art or nature we know not; probably both. Well, no—on second thoughts, not quite as deaf as a post, for by means of severe shouting she could be made to hear.

Smiles and nods, however, were her chief means of communication with the outer world. When these failed, a yell might be tried with advantage.

No one of the McKay household ever thought of giving Old Peg anything in the shape of work to do, for the very good reason that, being an extremely willing horse, she was always working; and she possessed a peculiar faculty of observation, which enabled her to perceive, long before any one else, what ought to be done, and the right time to do it, so that, when any one bounced round with the sudden intention of telling her to do anything, Old Peg was found to have done it already, or to be in the act of doing it. It is almost superfluous to say that she patched and mended the household garments, washed the most of things washable, sewed the sewable, darned the sock, and, generally, did-up the whole McKay family. When not engaged in definite or specific work, she had a chronic sock-knitting which helped to fill up and round off the corners of her leisure hours.

Old Peg had been the nurse, consecutively, of Fergus, Elspie, and Duncan junior. She was now equivalent to their second mother, having nursed their first mother to the end with faithful untiring affection, and received from the dying woman a solemn commission never to forsake Duncan senior or his progeny.

No sentiment of a religious nature ever escaped Old Peg, but it was observed that she read her Bible regularly, and was occasionally found asleep on her knees—greatly to the amusement of that irritable old rascal, Duncan senior, and to the gratification of Elspie, who came to the conclusion that the old woman must have learned well off by heart such words as—“Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do; do it with thy might.” “Do good to all men as thy hand findeth opportunity.” “Be clothed with humility.” “Trust in the Lord at all times.” Probably Elspie was right, for she judged of people in the old-fashioned way, namely, “by their fruits.” Her judgment of the two Duncans on this principle, by the way, could not have been very exalted, but we cannot tell. She was much too loyal and loving a daughter and sister to give any sign or opinion.

At the time of the sudden call to flight just described, the McKay family had totally forgotten Old Peg in their hurry. Elspie was the first to miss her.

“Old Peg!” she exclaimed—almost screamed—while Fergus was assisting her to mount Vixen, “where is she?”

“I’ll find her,” said Fergus, “and bring her on in the cart. You be off after father. We’ve no time to lose.”

“Be sure you bring her, Fergus,” said Elspie.

“All right; no fear!”

Thus assured, Elspie was about to gallop away after her father—who had started in advance, to overtake and stop the Prairie Cottage family, so that they might travel in one band—when the clatter of hoofs was heard, and next moment Dan Davidson galloped round the corner of the house.

“I came back for you, Elspie,” he said, pulling up. “Why did you not come on with your father?”

“I expected to overtake him, Dan. You know Vixen is swift. Besides, I missed Old Peg, and delayed a few minutes on her account. Is she with your party?”

“No—at least I did not see her. But she may have been in the cart with Louise. Shall I look for her while you gallop on?”

“No; Fergus has promised to find and bring her after us. Come, I am ready.”

The two galloped away. As they did so young Duncan issued from the stable behind the house, leading out his horse. He was in no hurry, having a good mount. At the same time Fergus came out at the back-door of the house shouting, “Old Peg! Hallo! old woman, where are ye?”

“Hev ye seen her, Duncan?” he asked impatiently.

“It iss seekin’ high an’ low I hev been, an’ it iss of no use shoutin’, for she hears nothin’.”

“I’m sure I saw her in the cart wi’ the Davidsons,” said Duncan.

“Are you sure?” asked Fergus.

“Weel, I did not pass quite close to them, as I ran up here for my horse on hearin’ the news,” replied Duncan; “but I am pretty sure that I saw her sittin’ beside Louise.”

“Hm! that accoonts for her not being here,” said Fergus, running into the stable. “Hold on a bit, Duncan. I’ll go with ye in a meenit.”

In the circumstances he was not long about saddling his horse. A few minutes more, and the brothers were galloping after their friends, who had got a considerable distance in advance of them by that time, and they did not overtake them till a part of the Settlement was reached where a strong muster of the settlers was taking place, and where it was resolved to make a stand and face the foe.

Here it was discovered, to the consternation of the McKay family, that Old Peg was not with the Davidson party, and that therefore she must have been left behind!

“She must be found and rescued,” exclaimed Elspie, on making the discovery.

“She must!” echoed Dan Davidson: “who will go back with me?”

A dozen stout young fellows at once rode to the front, and old McKay offered to take command of them, but was overruled and left behind.

Chapter Nine.

Old Peg

Meanwhile, accustomed to think and act for herself, Old Peg, on the first alarm, had made up her mind to do her fair share of work quietly.

She did not require to be told that danger threatened the family and that flight had been resolved on. A shout from some one that Nor’-Westers were coming, coupled with the hasty preparations, might have enlightened a mind much less intelligent than that of the old woman. She knew that she could do nothing to help where smart bodily exercise was needed, but, down by the creek close by, there was a small stable in which a sedate, lumbering old cart-horse dwelt. The horse, she felt sure, would be wanted. She could not harness it, but she could put a bridle on it and lead it up to the house.

This animal, which was named Elephant on account of its size, had been totally forgotten by the family in the hurry of departure.

Old Peg found the putting of a bridle on the huge creature more difficult work than she had expected, and only succeeded at last by dint of perseverance, standing on three or four bundles of hay, and much coaxing—for the creature had evidently taken it into its head that the old woman had come there to fondle it—perhaps to feed it with sugar after the manner of Elspie.

She managed the thing at last, however, and led the horse up towards the house.

Now, while she had been thus engaged the family had left, and the half-breeds—having combined their forces—had arrived.

Ben Nevis was the first house the scoundrels came to. Dismounting, and finding the place deserted, they helped themselves to whatever was attractive and portable—especially to a large quantity of Canada twist tobacco, which old Duncan had found it impossible to carry away. Then they applied fire to the mansion, and, in a wonderfully short time Ben Nevis was reduced to a level with the plain. Another party treated Prairie Cottage in a similar manner.

It was when the first volume of black smoke rose into the sky that Old Peg came to the edge of the bushes that fringed the creek and discovered that Ben Nevis had suddenly become volcanic! She instantly became fully aware of the state of matters, and rightly judged that the family must have escaped, else there would have been some evidence of resistance.

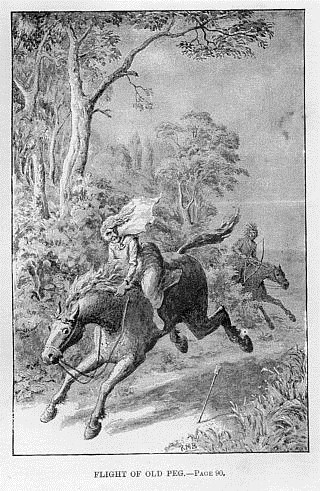

Fortunately the old woman had not yet passed quite from the shelter of the bushes. She drew back with a degree of caution worthy of a Red-skin, leading the horse with her. When well out of sight she paused for the purpose of meditation. What was now to be done! As we have said, she possessed decision of character in an eminent degree. She never at any time had taken long to make up her mind; she was not going to begin now, though the position was probably the most perplexing that she had ever experienced. Suddenly she raised her head and laughed.

In the circumstances it would not have been surprising had hysteria seized Old Peg, but there was nothing hysterical in her nature. Calm, cool, calculating courage dominated her every thought and feeling, but the idea of what she was driven to in her old age had tickled her fancy. Leading the big cart-horse close up to a bank, she prepared to mount him—having previously broken off a good strong switch from a neighbouring bush.

Never before in her life had Peg mounted a steed of any kind whatever. She knew the lady’s position on horseback by sight, of course, but not by practice. To attempt it even with a side-saddle would have been impossible; but Elephant was barebacked. Fortunately he was fat and broad, and without a visible back-bone. Old Peg at once made up her mind, and, climbing the bank, scrambled on his back in gentleman’s position. It was more comfortable than she had dared to hope.

But now an unexpected difficulty met her. Elephant declined to move! She pulled at his bridle, and he turned sluggishly, but he would not advance. Peg administered a sounding whack with the switch. She might as well have hit a neighbouring tree. Elephant’s hide was like that of his namesake, and he had no feelings to speak of that could be touched, or hurt, or worked upon.

In this dilemma the old woman had recourse to a weapon with which her broad bosom was at all times furnished. She drew a large pin, and drove the point into Elephant’s flank. The result was instantaneous. Up went his hindquarters, and Peg found herself sprawling on his bushy mane. She held on to that, however, and, gradually working her way back, regained her old position—thankful that she had not been thrown to the ground.

Another result was that Elephant condescended to walk. But this was not enough. Escape at such a pace was impossible. Old Peg prodded him again—this time on the shoulder, for she rightly conjectured that he could not well kick up with his fore-legs. But he might rear! The thought caused her to grasp the bushy mane with both hands and hold on. He did not rear, but he trotted, and poor Old Peg came to the conclusion that there were disagreeable novelties in life, even for her.

When Elephant at length burst out of the fringe of wood and gained the track that followed the course of the river, she was immediately seen by the plunderers, who laughed at the strange rider but did not follow her, with the exception of one man—an Indian, painted and feathered,—who started in pursuit, hoping, possibly, for an easy scalp.

He soon came close up, and, being armed with a bow, sent an arrow in advance of him. The shaft was well aimed. It grazed the flank of Elephant, inflicting a painful wound. This woke up the old horse surprisingly, so that it not only broke into a gallop, but set off at racing speed as it used to do when young. The Indian was badly mounted, and gradually lost ground, whereupon he sent after the fugitives several more arrows which all fell wide of the mark.

The change to Old Peg was as a reprieve from death! The trot had almost dislocated her bones, and shaken her up like an addled egg, and the change to racing speed afforded infinite relief. She could scarcely credit her senses, and she felt a tendency to laugh again as she glanced over her shoulder. But that glance removed the tendency, for it revealed the Indian warrior, in all his paint and feathers and streaming scalp-locks, in hot pursuit, while the whiz of another arrow close past her ear convinced our heroine that it was not a dream.

The jolting to which the poor old creature was subjected had disturbed her costume not a little. Her shawl came nearly off, and, holding on by one pin, fluttered like a flag of defiance. Her slippers, which were of the carpet pattern, were left behind on the prairie to perplex the wolves, and her voluminous hair—once a rich auburn, but now a pearly grey—having escaped its cap and fastenings, was streaming out gaily in the breeze, as if to tempt the fingers and knife of the pursuer.

A stern-chase is a long one, whether ashore or afloat. Pursuer and pursued went rapidly down the Settlement until they came in sight of the band which had come to rescue Peg. They received her with a wild cheer of surprise and joy, which turned the Red-skin to the right-about, and sent him back to his friends much faster than he had come.

On receiving his report, the half-breeds at once dashed off in pursuit of the settlers, and did not draw rein until they reached the place where the Scotchmen had made a stand. The latter were greatly outnumbered, at least in fighting men, but they showed such a resolute front, that Cuthbert Grant, the half-breed leader, again interfered to prevent bloodshed if possible. After calming his men, and advising forbearance, he turned to Duncan McKay senior, who was the settlers’ spokesman, and said—

“If you will go peaceably away out of the colony, we will spare you, but if you show fight your blood be on your own heads, for I cannot restrain my men much longer.”

“Iss it sparin’ us you will be talkin’ of, Cuthbert Grant?” answered the Highlander, with scorn. “Wow! but if it wass not for the weemen an’ children that’s with us, you would hev a goot chance o’ bein’ in need o’ sparin’ yoursels; an’ it iss not much o’ the blood o’ the Grants, either, that’s in your veins, or ye would scorn to consort wi’ such fire-raisin’ cut-throats. It iss the fortune of war—whatever, and we can’t affoord to leave our weemen an’ bairns defenceless. So we accept your terms, if we are not hindered from carryin’ away our arms.”

“Carry away whatever you like,” replied Grant, quietly, “only be off at once, or I’ll not answer for the consequences.”

Thus the angry Highlander was dismissed, and in the end the unfortunate settlers, being a second time driven into exile, took refuge, as before, at Jack River.

Chapter Ten.

Archie and Little Bill do Wonders

We change the scene now to the margin of a small lake embosomed like a gem in the great wilderness of the Far North.

It is autumn. The sun is bright, the air is calm and clear. There is a species of warm haze which, paradoxically, does not seem to interfere with the clearness, and a faint zephyr which appears rather to emphasise than break the calm. It sends a soft cat’s-paw now and then across parts of the lake, and thus, by contrast, brings into greater prominence the bright reflection of trees and cloudland mirrored in its depths. Instead of being the proverbial “dead” calm, it is, if we may so put it, rather a lively, cheerful calm.

The liveliness of it is vastly increased by hundreds of water-fowl, which disport themselves on the surface of the lake, as if coquetting with their own reflections, or whistle round its margin while busy on the feeding-grounds.

Myriads of mosquitoes were wont there to murmur their maddening career in search of blood, but, happily, at the period we write of, an incidental and premonitory night-frost had relegated these to the graves of their forefathers, or to the mansions of Hiberna—we know not, and care not, which.

We have styled the lake a “little” one, but we must remind the reader that we use the expression in an American sense, and that where lakes are two and three hundred miles long, a little one can well afford to be twenty or thirty miles in diameter, with, perchance, a boundless horizon. The lake in question, however, was really a little one—not more than two miles in length or breadth, with the opposite shore quite visible, and a number of islets of various sizes on its bosom—all more or less wooded, and all, more rather than less, the temporary homes of innumerable wild-fowl, among which were noisy little gulls with pure white bodies and bright red legs and bills.

On the morning in question—for the sun was not yet much above the horizon—a little birch-bark canoe might have been seen to glide noiselessly from a bed of rushes, and proceed quietly, yet swiftly, along the outer margin of the bed.

The bow-paddle was wielded by a stout boy with fair curly hair. Another boy, of gentle mien and sickly aspect, sat in the stern and steered.

“Little Bill,” said the stout boy in a low voice, “you’re too light. This will never do.”

“Archie,” returned the other with a languid smile, “I can’t help it, you know—at least not in a hurry. In course of time, if I eat frightfully, I may grow heavier, but just now there’s no remedy except the old one of a stone.”

“That’s true, Little Bill,” responded Archie with a perplexed look, as he glanced inquiringly along the shore; “nevertheless, if thought could make you heavier, you’d soon be all right, for you’re a powerful thinker. The old remedy, you see, is not available, for this side of the lake is low and swampy. I don’t see a single stone anywhere.”

“Never mind, get along; we’ll come to one soon, I dare say,” said the other, dipping his paddle more briskly over the side.

The point which troubled Archie Sinclair was the difference in weight between himself and his invalid brother, which, as he occupied the bow, resulted in the stern of the light craft being raised much too high out of the water. Of course this could have been remedied by their changing places, but that would have thrown the heavier work of the bow-paddle on the invalid, who happened also to be the better steersman of the two. A large stone placed in the stern would have been a simple and effective remedy, but, as we have seen, no large stone was procurable just then.

“It didn’t much matter in the clumsy wooden things at Red River,” said Archie, “but this egg-shell of Okématan’s is very different. Ho! there’s one at last,” he continued with animation as they rounded a point of land, and opened up a small bay, on the margin of which there were plenty of pebbles, and some large water-worn stones.

One of these having been placed in the stern of the canoe, and the balance thus rectified, the voyage was continued.

“Don’t you think that breakfast on one of these islets would be nice?” said Billie.

“Just the very thing that was in my mind, Little Bill,” answered his brother.

It was a curious peculiarity in this sturdy youth, that whatever his invalid brother wished, he immediately wished also. Similarly, when Billie didn’t desire anything, Archie did not desire it. In short Billie’s opinion was Archie’s opinion, and Billie’s will was Archie’s law. Not that Archie had no will or opinion of his own. On the contrary, he was quite sufficiently gifted in that way, but his love and profound pity for the poor and almost helpless invalid were such that in regard to him he had sunk his own will entirely. As to opinions—well, he did differ from him occasionally, but he did it mildly, and with an openness to conviction which was almost enviable. He called him Bill, Billie, or Little Bill, according to fancy at the moment.

Poor boys! The sudden death of both parents had been a terrible blow to them, and had intensified the tenderness with which the elder had constituted himself the guardian of the younger.

When the Scotch settlers were banished from the colony, pity, as well as friendship for their deceased parents, induced the Davidson family to adopt the boys, and now, in exile, they were out hunting by themselves to aid in replenishing the general store of provisions.

It need scarcely be said that at this period of the year the exiled colonists were not subjected to severe hardships, for the air was alive with wild-fowl returning south from their breeding-grounds, and the rivers and lakes were swarming with fish, many of them of excellent quality.

“This will do—won’t it?” said Archie, pointing with his paddle to an islet about a hundred yards in diameter.

“Yes, famously,” responded Little Bill, as he steered towards a shelving rock which formed a convenient landing-place.

The trees and shrubs covered the islet to the water’s edge with dense foliage, that glowed with all the gorgeous colouring for which North American woods in autumn are celebrated. An open grassy space just beyond the landing-place seemed to have been formed by nature for the express purpose of accommodating picnic parties.

“Nothing could have been better,” said Archie, drawing up the bow of the canoe, and stooping to lift his brother out.

“I think I’ll try to walk—it’s such a short bit,” said Billie.

“D’ye think so? well, I’ve no doubt you can do it, Little Bill, for you’ve got a brave spirit of your own, but there’s a wet bit o’ moss you’ll have to cross which you mayn’t have noticed. Would you like to be lifted over that, and so keep your moccasins dry?”

“Archie, you’re a humbug. You’re always trying to make me give you needless trouble.”

“Well, have it your own way, Little Bill. I’ll help you to walk up.”

“No, carry me,” said Billie, stretching out his arms; “I’ve changed my mind.”

“I will, if you prefer it, Little Bill,” said Archie, lifting his brother in his strong arms and setting him down on the convenient spot before referred to.

Billie was not altogether helpless. He could stand on his weak legs and even walk a little without support, but to tramp through the woods, or clamber up a hill, was to him an absolute impossibility. He had to content himself with enjoyments of a milder type. And, to do him justice, he seemed to have no difficulty in doing so. Perhaps he owed it to his mother, who had been a singularly contented woman and had taught Billie from his earliest years the truth that, “contentment, with godliness, is great gain.” Billie did not announce his belief in this truth, but he proclaimed it unwittingly by the more powerful force of example.