Полная версия

Throne of Jade

NAOMI NOVIK

Throne of Jade

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2006

Copyright © Temeraire LCC 2006

Naomi Novik asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007258727

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2015 ISBN: 9780007318575

Version: 2018-11-08

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Part I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part II

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part III

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

About the Author

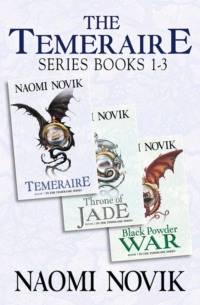

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Chapter One

The day was unseasonably warm for November, but in some misguided deference to the Chinese embassy, the fire in the Admiralty boardroom had been heaped excessively high, and Laurence was standing directly before it. He had dressed with especial care, in his best uniform, and all throughout the long and unbearable interview, the lining of his thick bottle-green broadcloth coat had been growing steadily more sodden with sweat.

Over the doorway, behind Lord Barham, the official indicator with its compass arrow showed the direction of the wind over the Channel: in the north-northeast today, fair for France; very likely even now some ships of the Channel fleet were standing in to have a look at Napoleon’s harbours. His shoulders held at attention, Laurence fixed his eyes upon the broad metal disk and tried to keep himself distracted with such speculation; he did not trust himself to meet the cold, unfriendly gaze fixed upon him.

Barham stopped speaking and coughed again into his fist; the elaborate phrases he had prepared sat not at all in his sailor’s mouth, and at the end of every awkward, halting line, he stopped and darted a look over at the Chinese with a nervous agitation that approached obsequiousness. It was not a very creditable performance, but under ordinary circumstances, Laurence would have felt a degree of sympathy for Barham’s position: some sort of formal message had been anticipated, even perhaps an envoy, but no one had ever imagined that the Emperor of China would send his own brother halfway around the world.

Prince Yongxing could, with a word, set their two nations at war; and there was besides something inherently awful in his presence: the impervious silence with which he met Barham’s every remark; the overwhelming splendour of his dark yellow robes, embroidered thickly with dragons; the slow and relentless tapping of his long, jewel-encrusted fingernail against the arm of his chair. He did not even look at Barham: he only stared directly across the table at Laurence, grim and thin-lipped.

His retinue was so large they filled the boardroom to the corners, a dozen guards all sweltering and dazed in their quilted armour and as many servants besides, most with nothing to do, only attendants of one sort or another, all of them standing along the far wall of the room and trying to stir the air with broad-panelled fans. One man, evidently a translator, stood behind the prince, murmuring when Yongxing lifted a hand, generally after one of Barham’s more involved periods.

Two other official envoys sat to Yongxing’s either side. These men had been presented to Laurence only perfunctorily, and they had neither of them said a word, though the younger, called Sun Kai, had been watching all the proceedings, impassively, and following the translator’s words with quiet attention. The elder, a big, round-bellied man with a tufted grey beard, had gradually been overcome by the heat: his head had sunk forward onto his chest, mouth half-open for air, and his hand was barely even moving his fan towards his face. They were robed in dark blue silk, almost as elaborately as the prince himself, and together they made an imposing façade: certainly no such embassy had ever been seen in the West.

A far more practised diplomat than Barham might have been pardoned for succumbing to some degree of servility, but Laurence was scarcely in any mood to be forgiving; though he was nearly more furious with himself, at having hoped for anything better. He had come expecting to plead his case, and privately in his heart he had even imagined a reprieve; instead he had been scolded in terms he would have scrupled to use to a raw lieutenant, and all in front of a foreign prince and his retinue, assembled like a tribunal to hear his crimes. Still he held his tongue as long as he could manage, but when Barham at last came about to saying, with an air of great condescension, ‘Naturally, Captain, we have it in mind that you shall be put to another hatchling, afterwards,’ Laurence had reached his limit.

‘No, sir,’ he said, breaking in. ‘I am sorry, but no: I will not do it, and as for another post, I must beg to be excused.’

Sitting beside Barham, Admiral Powys of the Aerial Corps had remained quite silent through the course of the meeting; now he only shook his head, without any appearance of surprise, and folded his hands together over his ample belly. Barham gave him a furious look and said to Laurence, ‘Perhaps I am not clear, Captain; this is not a request. You have been given your orders, you will carry them out.’

‘I will be hanged first,’ Laurence said flatly, past caring that he was speaking in such terms to the First Lord of the Admiralty: the death of his career if he had still been a naval officer, and it could scarcely do him any good even as an aviator. Yet if they meant to send Temeraire away, back to China, his career as an aviator was finished: he would never accept a position with any other dragon. None other would ever compare, to Laurence’s mind, and he would not subject a hatchling to being second-best when there were men in the Corps lined up six-deep for the chance.

Yongxing did not say anything, but his lips tightened; his attendants shifted and murmured amongst themselves in their own language. Laurence did not think he was imagining the hint of disdain in their tone, directed less at himself than at Barham; and the First Lord evidently shared the impression, his face growing mottled and choleric with the effort of preserving the appearance of calm. ‘By God, Laurence; if you imagine you can stand here in the middle of Whitehall and mutiny, you are wrong; I think perhaps you are forgetting that your first duty is to your country and your King; not to this dragon of yours.’

‘No, sir; it is you who are forgetting. It was for duty I put Temeraire into harness, sacrificing my naval rank, with no knowledge then that he was any breed truly out of the ordinary, much less a Celestial,’ Laurence said. ‘And for duty I took him through a difficult training and into a hard and dangerous service; for duty I have taken him into battle, and asked him to hazard his life and happiness. I will not answer such loyal service with lies and deceit.’

‘Enough noise, there,’ Barham said. ‘Anyone would think you were being asked to hand over your firstborn. I am sorry if you have made such a pet of the creature you cannot bear to lose him—’

‘Temeraire is neither my pet nor my property, sir,’ Laurence snapped. ‘He has served England and the King as much as I have, or you yourself, and now, because he does not choose to go back to China, you stand there and ask me to lie to him. I cannot imagine what claim to honour I should have if I agreed to it. Indeed,’ he added, unable to restrain himself, ‘I wonder that you should even have made the proposal; I wonder at it greatly.’

‘Oh, your soul to the devil, Laurence,’ Barham said, losing his last veneer of formality; he had been a serving sea-officer for years before joining the Government, and he was still very little a politician when his temper was up. ‘He is a Chinese dragon, it stands to reason he will like China better; in any case, he belongs to them, and there is an end to it. The name of thief is a very unpleasant one, and His Majesty’s Government does not propose to invite it.’

‘I know how I am to take that, I suppose.’ If Laurence had not already been half-broiled, he would have flushed. ‘And I utterly reject the accusation, sir. These gentlemen do not deny they had given the egg to France; we seized it from a French man-of-war; the ship and the egg were condemned as lawful prize out of hand in the Admiralty courts, as you very well know. By no possible understanding does Temeraire belong to them; if they were so anxious about letting a Celestial out of their hands, they ought not have given him away in the shell.’

Yongxing snorted and broke into their shouting-match. ‘That is correct,’ he said; his English was thickly-accented, formal and slow, but the measured cadences only lent all the more effect to his words. ‘From the first it was folly to let the second-born egg of Lung Tien Qian pass over sea. That, no one can now dispute.’

It silenced them both, and for a moment no one spoke, save the translator quietly rendering Yongxing’s words for the rest of the Chinese. Then Sun Kai unexpectedly said something in their tongue which made Yongxing look around at him sharply. Sun kept his head inclined deferentially, and did not look up, but still it was the first suggestion Laurence had seen that their embassy might perhaps not speak with a single voice. But Yongxing snapped a reply, in a tone which did not allow of any further comment, and Sun did not venture to make one. Satisfied that he had quelled his subordinate, Yongxing turned back to them and added, ‘Yet regardless of the evil chance that brought him into your hands, Lung Tien Xiang was meant to go to the French Emperor, not to be made beast of burden for a common soldier.’

Laurence stiffened; common soldier rankled, and for the first time he turned to look directly at the prince, meeting that cold, contemptuous gaze with an equally steady one. ‘We are at war with France, sir; if you choose to ally yourself with our enemies and send them material assistance, you can hardly complain when we take it in fair fight.’

‘Nonsense!’ Barham broke in, at once and loudly. ‘China is by no means an ally of France, by no means at all; we certainly do not view China as a French ally. You are not here to speak to His Imperial Highness, Laurence; control yourself,’ he added, in a savage undertone.

But Yongxing ignored the attempt at interruption. ‘And now you make piracy your defence?’ he said, contemptuous. ‘We do not concern ourselves with the customs of barbaric nations. How merchants and thieves agree to pillage one another is not of interest to the Celestial Throne, except when they choose to insult the Emperor as you have.’

‘No, Your Highness, no such thing, not in the least,’ Barham said hurriedly, even while he looked pure venom at Laurence. ‘His Majesty and his Government have nothing but the deepest affection for the Emperor; no insult would ever willingly be offered, I assure you. If we had only known of the extraordinary nature of the egg, of your objections, this situation would never have arisen—’

‘Now, however, you are well aware,’ Yongxing said, ‘and the insult remains: Lung Tien Xiang is still in harness, treated little better than a horse, expected to carry burdens and exposed to all the brutalities of war, and all this, with a mere captain as his companion. Better had his egg sunk to the bottom of the ocean!’

Appalled, Laurence was glad to see this callousness left Barham and Powys as staring and speechless as himself. Even among Yongxing’s own retinue, the translator flinched, shifting uneasily, and for once did not translate the prince’s words back into Chinese.

‘Sir, I assure you, since we learned of your objections, he has not been under harness at all, not a stitch of it,’ Barham said, recovering. ‘We have been at the greatest of pains to see to Temeraire’s – that is, to Lung Tien Xiang’s – comfort, and to make redress for any inadequacy in his treatment. He is no longer assigned to Captain Laurence, that I can assure you: they have not spoken these last two weeks.’

The reminder was a bitter one, and Laurence felt what little remained of his temper fraying away. ‘If either of you had any real concern for his comfort, you would consult his feelings, not your own desires,’ he said, his voice rising, a voice that had been trained to bellow orders through a gale. ‘You complain of having him under harness, and in the same breath ask me to trick him into chains, so you might drag him away against his will. I will not do it; I will never do it, and be damned to you all.’

Judging by his expression, Barham would have been glad to have Laurence himself dragged away in chains: eyes almost bulging, hands flat on the table, on the verge of rising; for the first time, Admiral Powys spoke, breaking in, and forestalled him. ‘Enough, Laurence, hold your tongue. Barham, nothing further can be served by keeping him. Out, Laurence; out at once: you are dismissed.’

The long habit of obedience held: Laurence flung himself out of the room. The intervention likely saved him from an arrest for insubordination, but he went with no sense of gratitude; a thousand things were pent up in his throat, and even as the door swung heavily shut behind him, he turned back. But the Marines stationed to either side were gazing at him with thoughtlessly rude interest, as if he were a curiosity exhibited for their entertainment. Under their open, inquisitive looks he mastered his temper a little, and turned away before he could betray himself more badly.

Barham’s words were swallowed by the heavy wood, but the inarticulate rumble of his still-raised voice followed Laurence down the corridor. He felt almost drunk with anger, his breath coming in short abrupt spurts and his vision obscured, not by tears, not at all by tears, except of rage. The antechamber of the Admiralty was full of sea-officers, clerks, political officials, even a green-coated aviator rushing through with dispatches. Laurence shouldered his way roughly to the doors, his shaking hands thrust deep into his coat pockets to conceal them from view.

He struck out into the crashing din of late afternoon London, Whitehall full of working men going home for their suppers, and the bawling of the hackney drivers and chairmen over all, crying, ‘Make a lane, there,’ through the crowds. His feelings were as disordered as his surroundings, and he was only navigating the street by instinct; he had to be called three times before he recognized his own name.

He turned only reluctantly: he had no desire to be forced to return a civil word or gesture from a former colleague. But with a measure of relief he saw it was Captain Roland, not an ignorant acquaintance. He was surprised to see her; very surprised, for her dragon, Excidium, was a formation-leader at the Dover covert. She could not easily have been spared from her duties, and in any case she could not come to the Admiralty openly, being a female officer, one of those whose existence was made necessary by the insistence of Longwings on female captains. The secret was but barely known outside the ranks of the aviators, and jealously kept against certain public disapproval; Laurence himself had found it difficult to accept the notion, at first, but he had now grown so used to the idea that now Roland looked very odd to him out of uniform: she had put on skirts and a heavy cloak by way of concealment, neither of which suited her.

‘I have been puffing after you for the last five minutes,’ she said, taking his arm as she reached him. ‘I was wandering about that great cavern of a building, waiting for you to come out, and then you went straight past me in such a ferocious hurry I could scarcely catch you. These clothes are a damned nuisance; I hope you appreciate the trouble I am taking for you, Laurence. But never mind,’ she said, her voice gentling. ‘I can see from your face that it did not go well: let us go and have some dinner, and you shall tell me everything.’

‘Thank you, Jane; I am glad to see you,’ he said, and let her turn him in the direction of her inn, though he did not think he could swallow. ‘How do you come to be here, though? Surely there is nothing wrong with Excidium?’

‘Nothing in the least, unless he has given himself indigestion,’ she said. ‘No; but Lily and Captain Harcourt are coming along splendidly, and so Lenton was able to assign them a double patrol and give me a few days of liberty. Excidium took it as excuse to eat three fat cows at once, the wretched greedy thing; he barely cracked an eyelid when I proposed my leaving him with Sanders – that is my new first lieutenant – and coming to bear you company. So I put together a street-going rig and came up with the courier. Oh hell: wait a minute, will you?’ She stopped and kicked vigorously, shaking her skirts loose: they were too long, and had caught on her heels.

He held her by the elbow so she did not topple over, and afterwards they continued on through the London streets at a slower pace. Roland’s mannish stride and her scarred face drew enough rude stares that Laurence began to glare at the passers-by who looked too long, though she herself paid them no mind; she noticed his behaviour, however, and said, ‘You are ferocious out of temper; do not frighten those poor girls. What did those fellows say to you at the Admiralty?’

‘You have heard, I suppose, that an embassy has come from China; they mean to take Temeraire back with them, and Government does not care to object. But evidently he will have none of it: tells them all to go hang themselves, though they have been at him for weeks now to go,’ Laurence said. As he spoke, a sharp sensation of pain, like a constriction just under his breastbone, made itself felt. He could picture quite clearly Temeraire kept nearly all alone in the old, worn-down London covert, scarcely used in the last hundred years, with neither Laurence nor his crew to keep him company, no one to read to him, and of his own kind, only a few small courier-beasts flying through on dispatch service.

‘Of course he will not go,’ Roland said. ‘I cannot believe they imagined they could persuade him to leave you. Surely they ought to know better; I have always heard the Chinese cried up as the very pinnacle of dragon-handlers.’

‘Their prince has made no secret he thinks very little of me; likely they expected Temeraire to share much the same opinion, and to be pleased to go back,’ Laurence said. ‘In any case, they grow tired of trying to persuade him; so that villain Barham ordered I should lie to him and say we were assigned to Gibraltar, all to get him aboard a transport and out to sea, too far for him to fly back to land, before he knew what they were about.’

‘Oh, infamous.’ Her hand tightened almost painfully on his arm. ‘Did Powys have nothing to say to it? I cannot believe he let them suggest such a thing to you; one cannot expect a naval officer to understand these things, but Powys should have explained matters to him.’

‘I dare say he can do nothing; he is only a serving officer, and Barham is appointed by the Ministry,’ Laurence said. ‘Powys at least saved me from putting my neck in a noose: I was too angry to control myself, and he sent me away.’

They had reached the Strand; the increase in traffic made conversation difficult, and they had to pay attention to avoid being splashed by the questionable grey slush heaped in the gutters, thrown up onto the pavement by the lumbering carts and hackney wheels. His anger ebbing away, Laurence was increasingly low in his spirits.

From the moment of separation, he had consoled himself with the daily expectation that it would soon end: the Chinese would soon see Temeraire did not wish to go, or the Admiralty would give up the attempt to placate them. It had seemed a cruel sentence even so; they had not been parted a full day’s time in the months since Temeraire’s hatching, and Laurence had scarcely known what to do with himself, or how to fill the hours. But even the two long weeks were nothing to this, the dreadful certainty that he had ruined all his chances. The Chinese would not yield, and the Ministry would find some way of getting Temeraire sent off to China in the end: they plainly had no objection to telling him a pack of lies for the purpose. Likely enough Barham would never consent to his seeing Temeraire now even for a last farewell.

Laurence had not even allowed himself to consider what his own life might be with Temeraire gone. Another dragon was of course an impossibility, and the Navy would not have him back now. He supposed he could take on a ship in the merchant fleet, or a privateer; but he did not think he would have the heart for it, and he had done well enough out of prize-money to live on. He could even marry and set up as a country gentleman; but that prospect, once so idyllic in his imagination, now seemed drab and colourless.

Worse yet, he could hardly look for sympathy: all his former acquaintance would call it a lucky escape, his family would rejoice, and the world would think nothing of his loss. By any measure, there was something ridiculous in his being so adrift: he had become an aviator quite unwillingly, only from the strongest sense of duty, and less than a year had passed since his change in station; yet already he could hardly consider the possibility. Only another aviator, perhaps indeed only another captain, would truly be able to understand his sentiments, and with Temeraire gone, he would be as severed from their company as aviators themselves were from the rest of the world.

The front room at the Crown and Anchor was not quiet, though it was still early for dinner by town standards. The place was not a fashionable establishment, nor even genteel, its custom mostly consisting of country-men used to a more reasonable hour for their food and drink. It was not the sort of place a respectable woman would have come, nor indeed the kind of place Laurence himself would have ever voluntarily frequented in earlier days. Roland drew some insolent stares, others only curious, but no one attempted any greater liberty: Laurence made an imposing figure beside her with his broad shoulders and his dress sword slung at his hip.