Полная версия

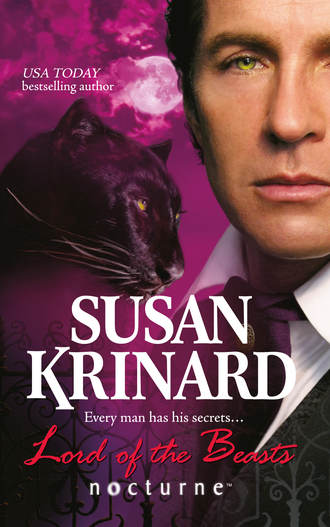

Lord of the Beasts

“Good morning,” Cordelia said crisply. “I am Mrs. Hardcastle, and this is Miss Shipp. We have come to see Dr. Fleming on a matter of some urgency.”

The old man blinked and let his gaze drift from Cordelia’s feet to the top of her bonnet. “T’ doctor is oot o’ t’ ‘oose at t’ moment,” he said.

Cordelia quickly translated the man’s thick dialect and nodded. “Can you tell me when he will return?”

“‘E’s with t’ coos in t’ byre yonder.”

“I see.” Cordelia suppressed a sigh and smiled patiently. “Perhaps you would be so kind as to tell him that he has visitors who wish to consult with him in his professional capacity?”

The old man grunted. “Weel, noo. ‘Appen Ah can fetch ‘im. If thoo’ll bide ‘ere …” He closed the door, leaving Cordelia staring at peeling blue paint.

“What did he say?” Theodora asked. “I didn’t understand a word.”

“He said he would fetch the doctor.” She shook her head. “Like master, like man. One can hardly expect courtesy from Dr. Fleming’s servants.”

“Perhaps it is simply the way of the people here.”

“Perhaps.” Grateful that she had worn sturdy boots, Cordelia lifted her skirts and set off across the somewhat muddy expanse of trampled earth between the farmhouse and the outbuildings scattered in a rough semicircle sheltered by rocky hills. A hay meadow stretched out to the east where the little valley was widest, and there were several fenced pastures between the byre and what appeared to be a stable. Drystone walls marched up the hills, undulating with the curves of the landscape.

She saw no other farmhands or laborers on her way to the byre, but of animals there were plenty. Chickens and geese wandered at will, snapping up grain and other tasty morsels spread out for them, and a pair of pigs had made a wallow where the mud was several feet deep. Horses in the pasture trotted up to the fence and poked inquisitive heads over the railing. A cat and five kittens paraded toward the meadow, tails twitching. Cows lowed and sheep bleated. Cordelia doubted that she would be surprised to find an elephant among the farm’s residents.

The servant’s gravelly voice floated from the byre, followed by the familiar, educated accent Cordelia had heard twice before. Lord Pettigrew had been somewhat vague when he had written of Dr. Fleming’s background; Cordelia suspected that he knew more than he was willing to tell, but he would surely not have dealings with a man whose past was less than respectable.

The social position of Dr. Fleming’s family was irrelevant to Cordelia’s purpose so long as he could provide the services she required. She turned to make certain that Theodora was behind her and picked her way to the byre’s doors.

“… did you tell her I was in, Benjamin?” Fleming was saying. “I’ve already received three letters from the woman, each one more demanding than the last. I haven’t time to cater to some fine lady’s pampered pets. The very fact that she has come all this way proves that she won’t be dissuaded unless she can be convinced—”

“Convinced of what, Dr. Fleming?” Cordelia said, stepping over the threshold. “That some gentlemen are so averse to human company that they will do anything to avoid it?”

Fleming shot to his feet from his place beside a spindly, spotted calf, and the flare of his green eyes stole the breath from Cordelia’s throat. He opened his mouth to speak, stared at Cordelia’s face, and seemed to forget what he was about to say.

“Ah told ‘er ta bide at t’ ‘oose,” Benjamin said mournfully, sending Cordelia a reproachful look.

His words seemed to shake Fleming from his paralysis. “I have no doubt,” he said. “Mrs. Hardcastle,” he said with a stiff bow, glancing past Cordelia to Theodora. “Miss Shipp. I trust you have not been waiting long.”

Cordelia matched his dry tone. “No longer than expected,” she said. “Have we interrupted you in your work?”

He looked down at the calf pressed against his leg and idly scratched it between the eyes. “Nothing that cannot wait.” He turned to Benjamin. “Put the poultice on his leg as I showed you, and I’ll see to him later.”

“Aye, Doctor.” Benjamin gave Cordelia a final, appraising look and knelt beside the calf. Fleming brushed off the sleeves of his coat—which, like his waistcoat, trousers and boots, was liberally splashed with mud—and started toward the door. Cordelia noted that he wore no cravat, and his shirt was open at the neck, revealing a dusting of reddish brown hair.

His face was as she remembered it, handsome and bronzed by a life spent outdoors. His brown hair was windblown and still in need of cutting. But he could barely restrain a scowl, and Cordelia felt that his slight attempts at courtesy were more for Theodora’s sake than her own.

“I apologize for my appearance,” he said, sounding not at all apologetic, “but I didn’t expect guests. I fear I lack adequate facilities to entertain ladies.”

“We are not here to be entertained,” Cordelia said.

He stopped, gestured the women ahead of him, and followed them out of the byre. “Have you come far this morning, Mrs. Hardcastle?”

“From York,” she said. “And previously by train from Gloucestershire.”

“A long journey.”

“Since I did not receive a reply to my letters,” Cordelia said, sidestepping a puddle, “I feared they had gone astray. One can never be sure of delivery in the countryside.”

Fleming cleared his throat and offered his arm to Theodora when she hesitated at a muddy patch. “I have been … much distracted since my return from London,” he said. “I am not a practiced correspondent.”

“Then you have read the letters.”

He released Theodora at the foot of the flagstone steps and faced Cordelia, his hands clasped behind his back. “Yes.” He glanced away. “Have you breakfasted this morning?”

“We have. Dr. Fleming …”

“Would you care to come in for tea?”

“I would not wish to put you to any trouble, Doctor.”

His eyes acknowledged her feint, and his lips curved up at the corners. “No. You would only have me abandon my practice and attend to your private menagerie in Gloucestershire.”

Theodora stifled what might have been a gasp. Cordelia returned Fleming’s smile. “Perhaps we shall accept your offer of tea, Doctor, if it will allow us to have a civilized conversation.”

Fleming bowed again, far too deeply, and opened the door to the house. “Please regard my humble kitchen as your own,” he said.

Humble the kitchen and house might be—certainly they bore no signs of luxury or a woman’s refining touch—but at least they were orderly and clean. Donal seated his guests at the long kitchen table and set about preparing the tea himself. As water heated on the massive stove, he disappeared and returned with a tray holding a pot of honey, a pitcher of cream and a plate of scones.

“We were fortunate to receive a fresh basket of scones from Mrs. Laverick this morning,” he said, deftly placing the pots and plates on the table. A moment later he set out a fine china teapot and dainty cups and saucers.

“How lovely,” Theodora said, unable to conceal her surprise.

“An inheritance from my mother,” Fleming said shortly. He completed the preparations in silence and strained the grounds into the teapot with the same grace he had shown in stopping a charging pachyderm. “Will you pour, Mrs. Hardcastle?”

She accepted his invitation and served the tea, which Fleming took absolutely plain. Once they had all spent a suitable time savoring the tea and scones, Fleming set down his cup and fixed his direct stare on Cordelia.

“It is not my intention to be rude, Mrs. Hardcastle, Miss Shipp,” he said, “but it is impossible for me to accede to your request.”

In spite of her previous meetings with him, Cordelia discovered that she could still be taken aback by his bluntness. She placed her cup on its saucer and folded her hands in her lap.

“Surely, since we have come so far, you will allow me to elaborate on the subject before you dismiss it,” she said.

He sighed. “Perhaps I misunderstood. Did you not suggest that I travel to your father’s estate in Gloucestershire to examine the animals in your private menagerie?”

“I did.” She held his gaze. “When we met at the Zoological Gardens, I was most impressed by your dealings with the elephant. I made inquiries based upon the assumption that you had some connection with the Zoological Society. Lord Pettigrew is an old acquaintance of my father, Sir Geoffrey Amesbury. He told me of your profession, and that you had come to London at his request. He said that you were able to improve the health of a tigress and several other exotic animals within only a few days.”

Fleming rose from the table and paced halfway across the room. “I went to London only because my family are also acquainted with Lord Pettigrew, and he presented his case as a matter of life or death for the animals concerned.”

Cordelia also rose. “Perhaps I was not clear enough in my letters. My case is also urgent.”

He came to stand at the opposite end of the room, pressed near the wall like a cornered animal prepared to fight for its life. “You wrote that your pets are suffering from a general malaise. This is hardly surprising in creatures forced to endure unnatural captivity.”

She held onto her temper. “You can hardly judge what you have not seen, Doctor.”

“I have seen cages,” he said, his voice growing distant and strange. “One is little different from another.”

“I do not agree. I, too, have seen cages, all over the world, and beasts nearly starved or beaten to death.” She swallowed her anger. “My animals receive care equal to that of the Zoological Gardens. Expense is no object where their well-being is concerned … and that includes generous compensation for an expert practitioner such as yourself.”

He emerged from the grip of memory and made a sound not unlike the snort of an irritated horse. “Sir Geoffrey Amesbury,” he said. “A knight?”

“My father is a baronet.”

“And your husband, Mrs. Hardcastle? Does he take an equal interest in your hobbies?”

She stared at him, abruptly realizing that she had never clarified her marital status. “My husband, Dr. Fleming, is deceased. I am a widow.”

Fleming gaped at her and then had the grace to look embarrassed at his faux pas. “I am sorry,” he said, tugging at his cravat. “I had not realized … When we first met in London, I had thought you unmarried. But your letters …”

“Were not perhaps as clear as they might have been,” Cordelia finished. “My father is often indisposed, and has left the administration of the estate in my hands. So you see, I possess all due authority to request your assistance at whatever price we both deem reasonable.”

Dr. Fleming was silent for several moments, regarding her as if she had confounded all his expectations. He collected the tea tray and carried it to a scarred sideboard. “You must be very comfortably situated, Mrs. Hardcastle,” he said at last. “My circumstances must seem extremely limited by comparison.”

“If I have judged you in any capacity,” Cordelia said, “it has not been by your family—of whom I know nothing—your profession, or your residence.”

“But you have judged that I must be in need of money.” He clasped his hands behind his back and gazed out the large kitchen window. “Do you believe that is my chief motive for the work I do, Mrs. Hardcastle? Are you attempting to bribe me with promises of fees I could never earn in such a backward place as this?”

Cordelia strode to join him, her skirts hissing like a goaded serpent. “It seems I remain most ignorant in matters of your character, Doctor. Pray enlighten me. Why does a man of your obvious skill, whose abilities are lauded by a personage such as Lord Pettigrew, choose to hide himself in the wilds of Yorkshire? Why does he so discourteously reject a respectable offer of employment to heal the very creatures whom he so obviously prefers to humankind?”

He turned on her, the color of his eyes shifting like leaves dancing in and out of shadow. “Tell me, Mrs. Hardcastle,” he said, “why can you not bear to be refused? Have you never met a man who declines to tremble in awe at the force of your indomitable will?”

His words hung in a sudden, shocked silence. Cordelia took a step back, her fists clenched at her sides, and tried to remember the last time any man had spoken to her with such contempt.

No, not contempt. She gathered calm about her like an Indian shawl and considered him with cool deliberation. She had been correct in her assessment of him: he was hiding, here among his animals, and anyone who might drive him into the open must be considered a threat. A threat to be chased away by any means necessary.

“You must have been hurt very badly,” she said, softly enough so that only he would hear. “I pity you, Doctor. I pity you more than I can say.”

Fleming blanched. For once he seemed unable to think of a suitably cutting response. Cordelia’s heart clenched with a pang of regret. Had she not spoken too rashly, out of pride and anger? Had she not sworn to herself a thousand times since returning to England that she would never again allow passions of any kind to rule her life?

She had opened her mouth to offer some sort of apology when a furious scratching began at the door. A moment later the door burst inward, and the dogs from the yard rushed toward Cordelia like a pack of wolves.

She braced herself, half expecting the pain of fangs tearing at her flesh. But the dogs, all nine or ten of them, simply ran around her and pressed against their master, licking his hands and whining as they milled about him. It was if they had sensed his distress and responded to it in the only way they could.

Their devoted attentions freed Fleming from his preoccupation. He met Cordelia’s eyes for only an instant and then walked past her to the door.

“Forgive me for this disturbance, ladies,” he said. “The animals of Stenwater Farm are accustomed to an unusual degree of liberty.” Something in his voice, and in the halftwist of his lips, suggested that he counted himself among the fortunate beasts. “May I offer you anything else before you return to York?”

The dismissal was gentle, and absolute. Theodora rose, her fingers pinching the folds of her skirt. Cordelia smiled at her reassuringly and led her toward the door. The time for apologies was past.

Dr. Fleming showed them the courtesy of escorting them to the road and summoning the coachman. The dogs watched from the porch, ears pricked and bodies quivering. The cat and her kittens leaped up on the drystone wall bordering the road and regarded Cordelia with haughty disapproval. Even the pigs heaved out of their wallow, complaining like old men grudgingly roused from a sound sleep.

Fleming’s expression was mild and disinterested as he handed the women into the carriage and wished them a pleasant journey. It was as if he and Cordelia had never exchanged a single barbed comment or harsh word. Cordelia brooded for all of a half-mile before she signaled the coachman to stop.

“This will not do,” she said. “This will not do at all.”

Theodora touched Cordelia’s arm. “Perhaps it is for the best,” she said quietly. “Surely you can find another veterinarian for the menagerie, one who is more congenial.”

Cordelia frowned. “Did you find him so unpleasant?”

“Not unpleasant. Unusual, perhaps.” Two vivid spots of color rose in her cheeks. “He does not seem to need anyone.”

“You notice more than you admit, my dear.”

“I noticed that you did not dislike him as much as you pretended.”

“Oh?”

“Forgive me, but it is true that you are not used to being refused. If that is the only reason you would … I mean …” She sank into the seat, avoiding Cordelia’s gaze.

Cordelia tapped her lower lip and stared out the window. Green, rolling hills marched away from the road, dotted here and there by clusters of sheep. She opened the carriage door and hopped to the ground without waiting for the coachman to let down the step.

“I think I’ll take a turn about that meadow,” she told Theodora. “The wildflowers are quite lovely. I shall only be a few minutes.”

Theodora offered no protest, and so Cordelia started at a brisk pace for the wall at the side of the road. She found a stile and entered the meadow, her skirts brushing the petals of cow parsley, yellow celandine and buttercup, blue forget-me-not and speedwell. Bees filled the air with their droning. Cordelia climbed to the top of the hill, letting her mind wander between the remote beauty of the Dales and the vexatious puzzle that was Dr. Donal Fleming.

She saw the figure in the white dress while it was still some distance away. At first Cordelia couldn’t judge either age or appearance, but as the girl came nearer it became apparent that she was no shepherdess or farmwife going about her daily chores. The young woman’s black hair fell loose about her shoulders. She wore no gloves or bonnet. Her gown was simple but well-cut, adorned with lace at bodice and sleeves, and the ruched skirts were too full for those of a working woman. She was walking directly toward Stenwater Farm, and a small brown-and-white spaniel trotted at her heels.

Curiosity aroused, Cordelia descended the hill to intercept the stranger. The young woman saw her and stopped, her slender form frozen as if she were considering flight. The spaniel pressed against her skirts.

“Good morning,” Cordelia said.

The girl, whose soft and pretty features proclaimed her to be no more than seventeen or eighteen years of age, performed a brief curtsey. “Good morning, ma’am,” she said. Her voice was cultured and held no trace of the local dialect that had been so distinct in Fleming’s servant.

“I hope I have not disturbed your walk,” Cordelia said. “I am a visitor to this county, but I have seen no one since I left Stenwater Farm.”

The girl’s bright blue eyes flew to Cordelia’s face. “Stenwater Farm?”

“Yes. Do you know it?”

“Yes. That is, I …” She stammered in confusion, lifted her chin, and thrust out her lip in defiance. “I am a friend of Dr. Fleming.”

“Are you indeed? I have just spoken with the doctor about his traveling to Gloucestershire to treat the animals in my menagerie.” She noted the dismay that briefly crossed the girl’s face. “What a charming little dog. What is his name?”

“Sir Reginald.” She looked to the west. “I beg your pardon, but I must—”

“How remiss of me,” Cordelia interrupted, offering her hand. “I am Mrs. Hardcastle.”

The girl’s grip was a bit too firm for strict courtesy. “I am pleased to make your acquaintance, Mrs. Hardcastle,” she said without sincerity. “I hope you will enjoy the remainder of your visit, but I must be on my way.” She had taken several steps before Cordelia caught up with her.

“Are you going to Stenwater Farm?” she asked. “I would be more than happy to conduct you there in my carriage.”

The girl cast Cordelia a frowning glance. “I often walk across the fells,” she said. “It is no trouble to me.”

“But you will ruin your lovely dress.”

Once more the girl seemed flustered, almost as if she had been caught in a lie. Without another word she rushed off, the hem of her skirts already stained green from the grass.

For reasons even she did not understand, Cordelia hurried back to the carriage and instructed the coachman to return the way they had come. Once the coach was within a few hundred yards of the lane to Stenwater Farm, Cordelia called another halt and climbed one of the hills that circled the farm to the east, moving as stealthily as her confining garments would allow.

She crested the hill just as the girl and her dog were approaching the byre from the rear. The young woman looked this way and that, obviously afraid of being seen, and entered the byre.

Cordelia weighed propriety against instinct, and for once she gave instinct its head. She half slid down the hill, watching for Fleming or his servant, and reached the bottom undetected. She found the back door to the byre and entered cautiously.

There was no immediate sign of the girl, but a flash of white in the darkness caught Cordelia’s eye. She found the grass-stained gown draped over the edge of the hayloft. When she was satisfied that the young woman had left the byre, Cordelia crept through the front door and looked across the yard.

It appeared that every one of Fleming’s animals had deserted the area, even the somnolent pigs. The silence was so complete that Cordelia could hear the sound of voices from the house … those of Dr. Fleming and a young girl. She lifted her skirts and dashed to the side of the house, keeping her body low.

“… must return to the Porritts, Ivy,” Fleming said, his words carrying distinctly out the half open window. “They will be worried.”

“Oi won’t go back,” the girl said. “Oi don’t loik them farmers. Oi wants to stay ‘ere, wiv you.”

Cordelia leaned against the wall to catch her breath and wondered how she had sunk so low as to sneak about like a common housebreaker and eavesdrop on a private conversation. And yet she sensed that there was something peculiar going on … particularly since the girl’s voice, apart from the thick London accent, was almost identical to that of the young woman she had met in the meadow.

“You don’t want me anymore,” the girl accused. “You brought me all the way up ‘ere, and then cast me off loik an ol’ pair o’ shoes.” She sniffled. “You’re cruel, Donal. Cruel ‘n’ mean.”

“No, Ivy. It isn’t that I don’t want you here. But you are better off with children your own age, and I don’t know how much longer I will be at Stenwater Farm. You have Sir Reginald—”

“Oi won’t go back!” She began to cry with great, gulping sobs. “Oi’ll jump roight off Newgill Scar, just see if Oi don’t!”

The thump of running feet was followed by the creak of hinges, and Ivy burst out the front door. Her gaze immediately fell on Cordelia.

“You!” she cried, and backed away so quickly that she almost stumbled on the flagstones. Cordelia absorbed the girl’s appearance in a heartbeat: the colorless dress, the bare feet, black hair swept up under a man’s frayed straw hat. But the shapeless frock could not quite conceal the womanly curves of her figure, and the dirt-smudged face was instantly familiar.

Ivy was not only the young lady with the white dress, but she was also the ragamuffin who had attempted to steal Inglesham’s purse in Convent Garden.

CHAPTER SIX

IVY GLANCED AT THE DOOR and then toward the byre, catching her lip between straight white teeth. The little spaniel planted itself in front of her and growled softly.

“Ivy,” Cordelia said, extending her hand. “You have nothing to fear from me.”

Fleming chose that moment to step outside. He looked from Ivy to Cordelia, his brows drawn low over his eyes, and folded his arms across his chest.

“Mrs. Hardcastle,” he said. “May I ask what you are you doing here?”

Cordelia had always believed that the best defense was a swift offense. “I might ask, Dr. Fleming,” she said, “what a certain young thief is doing in your house when she was last seen snatching purses in Covent Garden.”

Fleming stared at Cordelia, searching her eyes, and let his arms drop to his sides. “The answer is simple enough,” he said. “I found this child in Seven Dials, being assaulted by grown men, and did not consider it fitting to abandon her to such a life of squalor. I offered her a home in Yorkshire—” he shot a narrow glance at Ivy, as if he expected her to protest “—and that is why you find her here. The matter of your viscount’s purse was an unfortunate misunderstanding.”

“I see. A most admirable act on your part, Doctor, one that not many would emulate. It seems that not only the animals benefit from your compassion.” Cordelia caught Ivy’s gaze. “Do you agree with this description of events, Ivy?”

The girl hunched her shoulders but refused to speak. Cordelia nodded, unsurprised. “You helped her to escape in Covent Garden,” she said to Fleming.