Полная версия

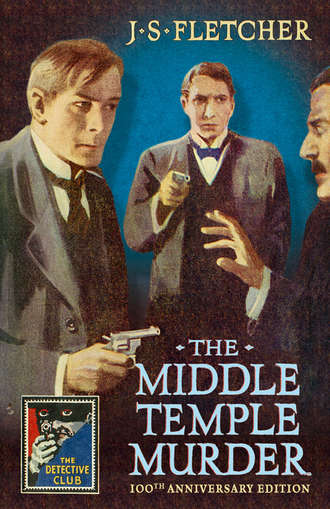

The Middle Temple Murder

‘Do you know Mr Elphick, Mr Spargo?’ enquired the younger Miss Aylmore.

‘I rather think I’ve seen him, somewhere about the Temple,’ answered Spargo. ‘In fact, I’m sure I have.’

‘His chambers are in Paper Buildings,’ said Jessie. ‘Sometimes he gives tea-parties in them. He is Ronald’s guardian, and preceptor, and mentor, and all that, and I suppose he’s dropped into this court to hear how his pupil goes on.’

‘Here is Ronald,’ whispered Miss Aylmore.

‘And here,’ said her sister, ‘is his lordship, looking very cross. Now, Mr Spargo, you’re in for it.’

Spargo, to tell the truth, paid little attention to what went on beneath him. The case which young Breton presently opened was a commercial one, involving certain rights and properties in a promissory note; it seemed to the journalist that Breton dealt with it very well, showing himself master of the financial details, and speaking with readiness and assurance. He was much more interested in his companions, and especially in the younger one, and he was meditating on how he could improve his further acquaintance when he awoke to the fact that the defence, realising that it stood no chance, had agreed to withdraw, and that Mr Justice Borrow was already giving judgment in Ronald Breton’s favour.

In another minute he was walking out of the gallery in rear of the two sisters.

‘Very good—very good, indeed,’ he said, absent-mindedly. ‘I thought he put his facts very clearly and concisely.’

Downstairs, in the corridor, Ronald Breton was talking to Mr Elphick. He pointed a finger at Spargo as the latter came up with the girls: Spargo gathered that Breton was speaking of the murder and of his, Spargo’s, connection with it. And directly they approached, he spoke.

‘This is Mr Spargo, sub-editor of the Watchman,’ Breton said. ‘Mr Elphick—Mr Spargo. I was just telling Mr Elphick, Spargo, that you saw this poor man soon after he was found.’

Spargo, glancing at Mr Elphick, saw that he was deeply interested. The elderly barrister took him—literally—by the button-hole.

‘My dear sir!’ he said. ‘You—saw this poor fellow? Lying dead—in the third entry down Middle Temple Lane! The third entry, eh?’

‘Yes,’ replied Spargo, simply. ‘I saw him. It was the third entry.’

‘Singular!’ said Mr Elphick, musingly. ‘I know a man who lives in that house. In fact, I visited him last night, and did not leave until nearly midnight. And this unfortunate man had Mr Ronald Breton’s name and address in his pocket?’

Spargo nodded. He looked at Breton, and pulled out his watch. Just then he had no idea of playing the part of informant to Mr Elphick.

‘Yes, that’s so,’ he answered shortly. Then, looking at Breton significantly, he added, ‘If you can give me those few minutes, now—?’

‘Yes—yes!’ responded Ronald Breton, nodding. ‘I understand. Evelyn—I’ll leave you and Jessie to Mr Elphick; I must go.’

Mr Elphick seized Spargo once more.

‘My dear sir!’ he said, eagerly. ‘Do you—do you think I could possibly see—the body?’

‘It’s at the mortuary,’ answered Spargo. ‘I don’t know what their regulations are.’

Then he escaped with Breton. They had crossed Fleet Street and were in the quieter shades of the Temple before Spargo spoke.

‘About what I wanted to say to you,’ he said at last. ‘It was—this. I—well, I’ve always wanted, as a journalist, to have a real big murder case. I think this is one. I want to go right into it—thoroughly, first and last. And—I think you can help me.’

‘How do you know that it is a murder case?’ asked Breton quietly.

‘It’s a murder case,’ answered Spargo, stolidly. ‘I feel it. Instinct, perhaps. I’m going to ferret out the truth. And it seems to me—’

He paused and gave his companion a sharp glance.

‘It seems to me,’ he presently continued, ‘that the clue lies in that scrap of paper. That paper and that man are connecting links between you and—somebody else.’

‘Possibly,’ agreed Breton. ‘You want to find the somebody else?’

‘I want you to help me to find the somebody else,’ answered Spargo. ‘I believe this is a big, very big affair: I want to do it. I don’t believe in police methods—much. By the by, I’m just going to meet Rathbury. He may have heard of something. Would you like to come?’

Breton ran into his chambers in King’s Bench Walk, left his gown and wig, and walked round with Spargo to the police office. Rathbury came out as they were stepping in.

‘Oh!’ he said. ‘Ah!—I’ve got what may be helpful, Mr Spargo. I told you I’d sent a man to Fiskie’s, the hatter! Well, he’s just returned. The cap which the dead man was wearing was bought at Fiskie’s yesterday afternoon, and it was sent to Mr Marbury, Room 20, at the Anglo-Orient Hotel.’

‘Where is that?’ asked Spargo.

‘Waterloo district,’ answered Rathbury. ‘A small house, I believe. Well, I’m going there. Are you coming?’

‘Yes,’ replied Spargo. ‘Of course. And Mr Breton wants to come, too.’

‘If I’m not in the way,’ said Breton.

Rathbury laughed.

‘Well, we may find out something about this scrap of paper,’ he observed. And he waved a signal to the nearest taxi-cab driver.

CHAPTER IV

THE ANGLO-ORIENT HOTEL

THE house at which Spargo and his companions presently drew up was an old-fashioned place in the immediate vicinity of Waterloo Railway Station—a plain-fronted, four-square erection, essentially mid-Victorian in appearance, and suggestive, somehow, of the very early days of railway travelling. Anything more in contrast with the modern ideas of a hotel it would have been difficult to find in London, and Ronald Breton said so as he and the others crossed the pavement.

‘And yet a good many people used to favour this place on their way to and from Southampton in the old days,’ remarked Rathbury. ‘And I daresay that old travellers, coming back from the East after a good many years’ absence, still rush in here. You see, it’s close to the station, and travellers have a knack of walking into the nearest place when they’ve a few thousand miles of steamboat and railway train behind them. Look there, now!’ They had crossed the threshold as the detective spoke, and as they entered a square, heavily-furnished hall, he made a sidelong motion of his head towards a bar on the left, wherein stood or lounged a number of men who from their general appearance, their slouched hats, and their bronzed faces appeared to be Colonials, or at any rate to have spent a good part of their time beneath Oriental skies. There was a murmur of tongues that had a Colonial accent in it; an aroma of tobacco that suggested Sumatra and Trichinopoly, and Rathbury wagged his head sagely. ‘Lay you anything the dead man was a Colonial, Mr Spargo,’ he remarked. ‘Well, now, I suppose that’s the landlord and landlady.’

There was an office facing them, at the rear of the hall, and a man and woman were regarding them from a box window which opened above a ledge on which lay a register book. They were middle-aged folk: the man, a fleshy, round-faced, somewhat pompous-looking individual, who might at some time have been a butler; the woman, a tall, spare-figured, thin-featured, sharp-eyed person, who examined the newcomers with an enquiring gaze. Rathbury went up to them with easy confidence.

‘You the landlord of this house, sir?’ he asked. ‘Mr Walters? Just so—and Mrs Walters, I presume?’

The landlord made a stiff bow and looked sharply at his questioner.

‘What can I do for you, sir?’ he enquired.

‘A little matter of business, Mr Walters,’ replied Rathbury, pulling out a card. ‘You’ll see there who I am—Detective-Sergeant Rathbury, of the Yard. This is Mr Frank Spargo, a newspaper man; this is Mr Ronald Breton, a barrister.’

The landlady, hearing their names and description, pointed to a side door, and signed Rathbury and his companions to pass through. Obeying her pointed finger, they found themselves in a small private parlour. Walters closed the two doors which led into it and looked at his principal visitor.

‘What is it, Mr Rathbury?’ he enquired. ‘Anything wrong?’

‘We want a bit of information,’ answered Rathbury, almost with indifference.

‘Did anybody of the name of Marbury put up here yesterday—elderly man, grey hair, fresh complexion?’

Mrs Walters started, glancing at her husband.

‘There!’ she exclaimed. ‘I knew some enquiry would be made. Yes—a Mr Marbury took a room here yesterday morning, just after the noon train got in from Southampton. Number 20 he took. But—he didn’t use it last night. He went out—very late—and he never came back.’

Rathbury nodded. Answering a sign from the landlord, he took a chair and, sitting down, looked at Mrs Walters.

‘What made you think some enquiry would be made, ma’am?’ he asked. ‘Had you noticed anything?’

Mrs Walters seemed a little confused by this direct question. Her husband gave vent to a species of growl.

‘Nothing to notice,’ he muttered. ‘Her way of speaking—that’s all.’

‘Well—why I said that was this,’ said the landlady. ‘He happened to tell us, did Mr Marbury, that he hadn’t been in London for over twenty years, and couldn’t remember anything about it—him, he said, never having known much about London at any time. And, of course, when he went out so late and never came back, why, naturally, I thought something had happened to him, and that there’d be enquiries made.’

‘Just so—just so!’ said Rathbury. ‘So you would, ma’am—so you would. Well, something has happened to him. He’s dead. What’s more, there’s strong reason to think he was murdered.’

Mr and Mrs Walters received this announcement with proper surprise and horror, and the landlord suggested a little refreshment to his visitors. Spargo and Breton declined, on the ground that they had work to do during the afternoon; Rathbury accepted it, evidently as a matter of course.

‘My respects,’ he said, lifting his glass. ‘Well, now, perhaps you’ll just tell me what you know of this man? I may as well tell you, Mr and Mrs Walters, that he was found dead in Middle Temple Lane this morning, at a quarter to three; that there wasn’t anything on him but his clothes and a scrap of paper which bore this gentleman’s name and address; that this gentleman knows nothing whatever of him, and that I traced him here because he bought a cap at a West End hatter’s yesterday, and had it sent to your hotel.’

‘Yes,’ said Mrs Walters quickly, ‘that’s so. And he went out in that cap last night. Well—we don’t know much about him. As I said, he came in here about a quarter past twelve yesterday morning, and booked Number 20. He had a porter with him that brought a trunk and a bag—they’re in 20 now, of course. He told me that he had stayed at this house over twenty years ago, on his way to Australia—that, of course, was long before we took it. And he signed his name in the book as John Marbury.’

‘We’ll look at that, if you please,’ said Rathbury.

Walters fetched in the register and turned the leaf to the previous day’s entries. They all bent over the dead man’s writing.

‘“John Marbury, Coolumbidgee, New South Wales,”’ said Rathbury. ‘Ah—now I was wondering if that writing would be the same as that on the scrap of paper, Mr Breton. But, you see, it isn’t—it’s quite different.’

‘Quite different,’ said Breton. He, too, was regarding the handwriting with great interest. And Rathbury noticed his keen inspection of it, and asked another question.

‘Ever seen that writing before?’ he suggested.

‘Never,’ answered Breton. ‘And yet—there’s something very familiar about it.’

‘Then the probability is that you have seen it before,’ remarked Rathbury. ‘Well—now we’ll hear a little more about Marbury’s doings here. Just tell me all you know, Mr and Mrs Walters.’

‘My wife knows most,’ said Walters. ‘I scarcely saw the man—I don’t remember speaking with him.’

‘No,’ said Mrs Walters. ‘You didn’t—you weren’t much in his way. Well,’ she continued, ‘I showed him up to his room. He talked a bit—said he’d just landed at Southampton from Melbourne.’

‘Did he mention his ship?’ asked Rathbury. ‘But if he didn’t, it doesn’t matter, for we can find out.’

‘I believe the name’s on his things,’ answered the landlady. ‘There are some labels of that sort. Well, he asked for a chop to be cooked for him at once, as he was going out. He had his chop, and he went out at exactly one o’clock, saying to me that he expected he’d get lost, as he didn’t know London well at any time, and shouldn’t know it at all now. He went outside there—I saw him—looked about him and walked off towards Blackfriars way. During the afternoon the cap you spoke of came for him—from Fiskie’s. So, of course, I judged he’d been Piccadilly way. But he himself never came in until ten o’clock. And then he brought a gentleman with him.’

‘Aye?’ said Rathbury. ‘A gentleman, now? Did you see him?’

‘Just,’ replied the landlady. ‘They went straight up to 20, and I just caught a mere glimpse of the gentleman as they turned up the stairs. A tall, well-built gentleman, with a grey beard, very well dressed as far as I could see, with a top hat and a white silk muffler round his throat, and carrying an umbrella.’

‘And they went to Marbury’s room?’ said Rathbury. ‘What then?’

‘Well, then, Mr Marbury rang for some whisky and soda,’ continued Mrs Walters. ‘He was particular to have a decanter of whisky: that, and a syphon of soda were taken up there. I heard nothing more until nearly midnight; then the hall-porter told me that the gentleman in 20 had gone out, and had asked him if there was a night-porter—as, of course, there is. He went out at half-past eleven.’

‘And the other gentleman?’ asked Rathbury.

‘The other gentleman,’ answered the landlady, ‘went out with him. The hall-porter said they turned towards the station. And that was the last anybody in this house saw of Mr Marbury. He certainly never came back.’

‘That,’ observed Rathbury with a quiet smile, ‘that is quite certain, ma’am? Well—I suppose we’d better see this Number 20 room, and have a look at what he left there.’

‘Everything,’ said Mrs Walters, ‘is just as he left it. Nothing’s been touched.’

It seemed to two of the visitors that there was little to touch. On the dressing-table lay a few ordinary articles of toilet—none of them of any quality or value: the dead man had evidently been satisfied with the plain necessities of life. An overcoat hung from a peg: Rathbury, without ceremony, went through its pockets; just as unceremoniously he proceeded to examine trunk and bag, and finding both unlocked, he laid out on the bed every article they contained and examined each separately and carefully. And he found nothing whereby he could gather any clue to the dead owner’s identity.

‘There you are!’ he said, making an end of his task. ‘You see, it’s just the same with these things as with the clothes he had on him. There are no papers—there’s nothing to tell who he was, what he was after, where he’d come from—though that we may find out in other ways. But it’s not often that a man travels without some clue to his identity. Beyond the fact that some of this linen was, you see, bought in Melbourne, we know nothing of him. Yet he must have had papers and money on him. Did you see anything of his money, now, ma’am?’ he asked, suddenly turning to Mrs Walters. ‘Did he pull out his purse in your presence, now?’

‘Yes,’ answered the landlady, with promptitude. ‘He came into the bar for a drink after he’d been up to his room. He pulled out a handful of gold when he paid for it—a whole handful. There must have been some thirty to forty sovereigns and half-sovereigns.’

‘And he hadn’t a penny piece on him—when found,’ muttered Rathbury.

‘I noticed another thing, too,’ remarked the landlady. ‘He was wearing a very fine gold watch and chain, and had a splendid ring on his left hand—little finger—gold, with a big diamond in it.’

‘Yes,’ said the detective, thoughtfully, ‘I noticed that he’d worn a ring, and that it had been a bit tight for him. Well—now there’s only one thing to ask about. Did your chambermaid notice if he left any torn paper around—tore any letters up, or anything like that?’

But the chambermaid, produced, had not noticed anything of the sort; on the contrary, the gentleman of Number 20 had left his room very tidy indeed. So Rathbury intimated that he had no more to ask, and nothing further to say, just then, and he bade the landlord and landlady of the Anglo-Orient Hotel good morning, and went away, followed by the two young men.

‘What next?’ asked Spargo, as they gained the street.

‘The next thing,’ answered Rathbury, ‘is to find the man with whom Marbury left this hotel last night.’

‘And how’s that to be done?’ asked Spargo.

‘At present,’ replied Rathbury, ‘I don’t know.’

And with a careless nod, he walked off, apparently desirous of being alone.

CHAPTER V

SPARGO WISHES TO SPECIALISE

THE barrister and the journalist, left thus unceremoniously on a crowded pavement, looked at each other. Breton laughed.

‘We don’t seem to have gained much information,’ he remarked. ‘I’m about as wise as ever.’

‘No—wiser,’ said Spargo. ‘At any rate, I am. I know now that this dead man called himself John Marbury; that he came from Australia; that he only landed at Southampton yesterday morning, and that he was in the company last night of a man whom we have had described to us—a tall, grey-bearded, well-dressed man, presumably a gentleman.’

Breton shrugged his shoulders.

‘I should say that description would fit a hundred thousand men in London,’ he remarked.

‘Exactly—so it would,’ answered Spargo. ‘But we know that it was one of the hundred thousand, or half-million, if you like. The thing is to find that one—the one.’

‘And you think you can do it?’

‘I think I’m going to have a big try at it.’

Breton shrugged his shoulders again.

‘What?—by going up to every man who answers the description, and saying “Sir, are you the man who accompanied John Marbury to the Anglo—”’

Spargo suddenly interrupted him.

‘Look here!’ he said. ‘Didn’t you say that you knew a man who lives in that block in the entry of which Marbury was found?’

‘No, I didn’t,’ answered Breton. ‘It was Mr Elphick who said that. All the same, I do know that man—he’s Mr Cardlestone, another barrister. He and Mr Elphick are friends—they’re both enthusiastic philatelists—stamp collectors, you know—and I dare say Mr Elphick was round there last night examining something new Cardlestone’s got hold of. Why?’

‘I’d like to go round there and make some enquiries,’ replied Spargo. ‘If you’d be kind enough to—’

‘Oh, I’ll go with you!’ responded Breton, with alacrity. ‘I’m just as keen about this business as you are, Spargo! I want to know who this man Marbury is, and how he came to have my name and address on him. Now, if I had been a well-known man in my profession, you know, why—’

‘Yes,’ said Spargo, as they got into a cab, ‘yes, that would have explained a lot. It seems to me that we’ll get at the murderer through that scrap of paper a lot quicker than through Rathbury’s line. Yes, that’s what I think.’

Breton looked at his companion with interest.

‘But—you don’t know what Rathbury’s line is,’ he remarked.

‘Yes, I do,’ said Spargo. ‘Rathbury’s gone off to discover who the man is with whom Marbury left the Anglo-Orient Hotel last night. That’s his line.’ ‘And you want—?’

‘I want to find out the full significance of that bit of paper, and who wrote it,’ answered Spargo. ‘I want to know why that old man was coming to you when he was murdered.’

Breton started.

‘By Jove!’ he exclaimed. ‘I—I never thought of that. You—you really think he was coming to me when he was struck down?’

‘Certain. Hadn’t he got an address in the Temple? Wasn’t he in the Temple? Of course, he was trying to find you.’

‘But—the late hour?’

‘No matter. How else can you explain his presence in the Temple? I think he was asking his way. That’s why I want to make some enquiries in this block.’

It appeared to Spargo that a considerable number of people, chiefly of the office-boy variety, were desirous of making enquiries about the dead man. Being luncheon-hour, that bit of Middle Temple Lane where the body was found was thick with the inquisitive and the sensation-seeker, for the news of the murder had spread, and though there was nothing to see but the bare stones on which the body had lain, there were more open mouths and staring eyes around the entry than Spargo had seen for many a day. And the nuisance had become so great that the occupants of the adjacent chambers had sent for a policeman to move the curious away, and when Spargo and his companion presented themselves at the entry this policeman was being lectured as to his duties by a little weazen-faced gentleman, in very snuffy and old-fashioned garments and an ancient silk hat, who was obviously greatly exercised by the unwonted commotion.

‘Drive them all out into the street!’ exclaimed this personage. ‘Drive them all away, constable—into Fleet Street or upon the Embankment—anywhere, so long as you rid this place of them. This is a disgrace, and an inconvenience, a nuisance, a—’

‘That’s old Cardlestone,’ whispered Breton. ‘He’s always irascible, and I don’t suppose we’ll get anything out of him. Mr Cardlestone,’ he continued, making his way up to the old gentleman who was now retreating up the stone steps, brandishing an umbrella as ancient as himself. ‘I was just coming to see you, sir. This is Mr Spargo, a journalist, who is much interested in this murder. He—’

‘I know nothing about the murder, my dear sir!’ exclaimed Mr Cardlestone. ‘And I never talk to journalists—a pack of busybodies, sir, saving your presence. I am not aware that any murder has been committed, and I object to my doorway being filled by a pack of office boys and street loungers. Murder indeed! I suppose the man fell down these steps and broke his neck—drunk, most likely.’

He opened his outer door as he spoke, and Breton, with a reassuring smile and a nod at Spargo, followed him into his chambers on the first landing, motioning the journalist to keep at their heels.

‘Mr Elphick tells me that he was with you until a late hour last evening, Mr Cardlestone,’ he said. ‘Of course, neither of you heard anything suspicious?’

‘What should we hear that was suspicious in the Temple, sir?’ demanded Mr Cardlestone, angrily. ‘I hope the Temple is free from that sort of thing, young Mr Breton. Your respected guardian and myself had a quiet evening on our usual peaceful pursuits, and when he went away all was as quiet as the grave, sir. What may have gone on in the chambers above and around me I know not! Fortunately, our walls are thick, sir—substantial. I say, sir, the man probably fell down and broke his neck. What he was doing here, I do not presume to say.’

‘Well, it’s guess, you know, Mr Cardlestone,’ remarked Breton, again winking at Spargo. ‘But all that was found on this man was a scrap of paper on which my name and address were written. That’s practically all that was known of him, except that he’d just arrived from Australia.’

Mr Cardlestone suddenly turned on the young barrister with a sharp, acute glance.

‘Eh?’ he exclaimed. ‘What’s this? You say this man had your name and address on him, young Breton!—yours? And that he came from—Australia?’

‘That’s so,’ answered Breton. ‘That’s all that’s known.’

Mr Cardlestone put aside his umbrella, produced a bandanna handkerchief of strong colours, and blew his nose in a reflective fashion.

‘That’s a mysterious thing,’ he observed. ‘Um—does Elphick know all that?’

Breton looked at Spargo as if he was asking him for an explanation of Mr Cardlestone’s altered manner. And Spargo took up the conversation.

‘No,’ he said. ‘All that Mr Elphick knows is that Mr Ronald Breton’s name and address were on the scrap of paper found on the body. Mr Elphick’—here Spargo paused and looked at Breton— ‘Mr Elphick,’ he presently continued, slowly transferring his glance to the old barrister, ‘spoke of going to view the body.’