полная версия

полная версияThe Dash for Khartoum: A Tale of the Nile Expedition

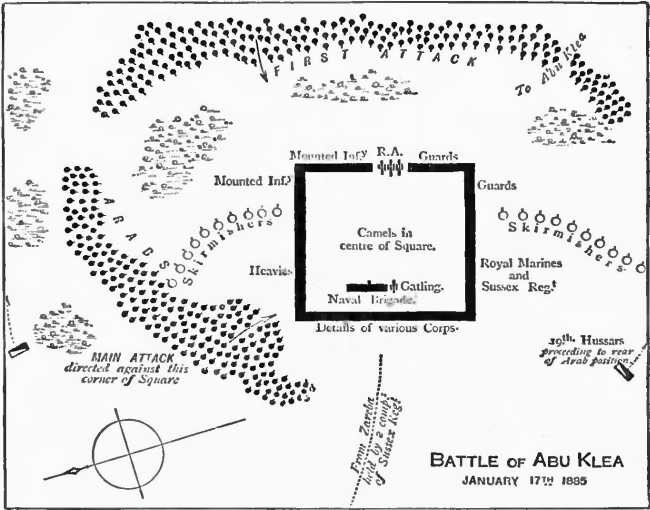

Battle of Abu Klea

January 17th 1885

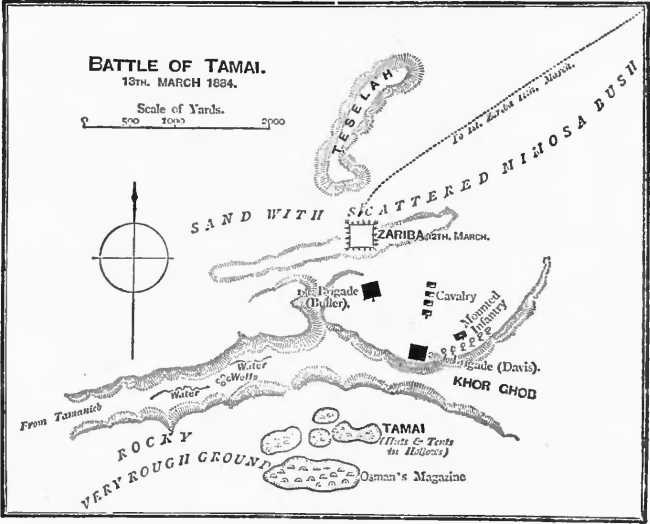

Battle of Tamai.

13th MARCH 1885.

The right companies of the 65th tried to form up to meet them, while Lieutenant Graham, R.N., with the men of the Naval Brigade working the three machine-guns under his command, threw himself into the gap. But the yells of the enemy and the roar of musketry rendered it impossible for the men to hear the orders given, and before the 65th had formed up the enemy were close at hand. Their fire and that of the Gatlings mowed down the Arabs in hundreds, but the wild mob charged on. Some hurled themselves on to the 65th, others poured like a wave over the little group of sailors, while the rest, dashing through the gap, flung themselves on the rear of the 42d.

The sergeants, whose place is in rear of the men, were cut down almost to a man; and the rear rank, facing round, were at once engaged in a desperate hand-to-hand fight with the natives. All was now confusion. Fresh masses of the enemy poured down with exulting shouts, and in a confused crowd the brigade retreated. Had not help been at hand they would probably have met with the same fate that befell Baker's force, and none would have reached Suakim to tell the news of the massacre. The sailors, in vain trying to drag off their guns, were almost all killed, and the guns fell into the hands of the enemy.

But a check was given to the advance of the Arabs by the cavalry, who had moved forward to the left of the square. The officer in command saw that were he to charge across the broken ground his little force would be lost among the throng of Arabs. He therefore dismounted them, and they poured volley after volley with their carbines into the thick of the enemy. In the meantime General Buller's square was advancing. It had been attacked as desperately as had that of General Davis; but it was well handled, and its formation had not been broken up by any order such as that which had destroyed the formation of the other brigade. So steady and terrible a fire was opened upon the advancing enemy that not one of the assailants reached the face of the square; and having repulsed the attacks, it advanced rapidly to the relief of the shattered brigade ahead, pouring incessant volleys into the ranks of the Arabs as they swept down to its assault.

Thus, as they advanced, the first brigade cleared the right face of the second from its foes, and as soon as they came up with the retreating force these halted and reformed their ranks Both brigades were now formed in line, and advanced steadily towards the ravine. Upon their way they came upon the abandoned guns, which the enemy had in vain tried to carry off. Sweeping the Arabs before them, the British force reached the edge of the ravine. It was filled by the flying Arabs, and into these a terrible fire was poured by the musketry and guns until the Arabs had gained the opposite side and were concealed among the bushes. The fighting was now over, although the enemy still maintained a distant fire. It was necessary, however, to keep the troops together, for numbers of the Arabs still lay hidden among the bushes, leaping up and flinging themselves desperately upon any who approached them.

The scene of the conflict was terrible. A hundred and twenty of the British lay dead, of whom more than half belonged to the 42d. Three naval officers and ten sailors were killed, while a large number of officers and men of the 42d and 65th were seriously wounded. The slaughter among the natives had been very great—no less than four thousand of them strewing the ground in all directions. The British wounded were sent back to the zareba, and the force again advanced. Crossing the ravine they made towards three villages in its rear. Here was Osman Digma's camp, and the Arabs mustering in strength again opened a heavy fire. They were, however, unable to withstand the British guns and the heavy volleys of the infantry, and the troops advanced into the camp.

It was found filled with property of all kinds; for the Arabs had removed nothing, making perfectly sure that they should be able to repel the English advance. Bags of money, bundles of clothing, Korans, great quantities of grain, and plunder of all kinds were found in the huts. Osman Digma himself had taken no part whatever in the fight. He had looked on from a distant eminence, and when he saw the repulse of the Arab attack and the flight of his men he at once made off.

The next day the cavalry went on to a village two or three miles distant. Here they found a great quantity of ammunition for Krupp cannon and other loot, which had been captured from the forces of Baker and Moncrieff. The village was burnt and the ammunition blown up.

The next day the force started on its return march, after burning and destroying Osman's camp and the three adjoining villages. No attempt was made to pursue Osman Digma or his Arabs. The country beyond was steep and mountainous, and there would have been no chance whatever of overtaking and capturing him, while the troops might have been attacked in difficult positions and have suffered heavily.

It was supposed that after the two crushing defeats that had been inflicted on the enemy, and the proof so afforded of the falsehood of Osman Digma's pretensions, the tribesmen would no longer believe in him, and that his authority would have been altogether destroyed. The expectation was not, however, justified by events, for two years later the Arabs again mustered under him in such formidable numbers, that another expedition was necessary to protect Suakim against the gathering of fanatics reassembled under Osman's banner.

The cavalry had suffered no loss during the operations, and as they had had some share in the fighting, and had materially aided the shattered brigade by their fire upon the Arabs, they were not ill satisfied that they had not been called upon to take a more prominent part in the operations.

But little time was lost at Suakim. The greater part of the troops were at once embarked on the transports and taken up to Suez, a small body only being left to protect the town should the Arabs again gather in force. The policy was a short-sighted one. Had a protectorate been established over the country to the foot of the hills, and a force sufficient to maintain it left there, the great bulk of the tribesmen would have willingly given in their allegiance, and no further hostile movement upon the part of Osman Digma would have been possible; but the fact that we hastened away after fighting, and afforded no protection whatever to the friendly natives, effectually deterred others from throwing in their lot with us, and enabled Osman Digma gradually to restore his power and influence among them.

Short though the campaign had been it had the effect of causing some inflammation in Edgar's wounds, and as soon as the expedition returned to the coast the surgeon ordered him into hospital, and it was six weeks before he again took his place in the ranks. By this time the regiment was re-united at Cairo, and there was for some months nothing to break the even tenor of their way.

Long ere this Edgar had learnt that his recommendation for the Victoria Cross had not been acceded to. This, however, was no surprise, for after what he had heard from Major Horsley he had entertained but little hope that he would be among the favoured recipients of the cross.

"Never mind, Ned," a comrade said to him when the list was published and his name was found to be absent. "It is not always those that most deserve the cross who get it. We know that you ought to have had it, if any fellow ever did, and we shall think just as much of you as if you had got it on your breast."

In spite of the heat cricket matches were got up at Cairo, and the Hussars distinguished themselves here as they had done at Aldershot. The chief topic of interest, however, was the question of the safety of Khartoum, and especially that of General Gordon. He had been sent out by the British government in hopes that the great influence he possessed among the natives might enable him to put a stop to the disorder that prevailed in the Soudan. At the time that he had been in the service of the Egyptian government he had ruled so wisely and well in the Soudan that his prestige among the natives was enormous. He had suppressed slave-trading and restored order throughout the wide province, and by mingling mercy with justice he was at once admired and feared even by those whose profits had been annihilated by the abolition of the slave-trade.

But although Gordon had been rapturously received by the inhabitants of Khartoum, the tribes of the Soudan had not rallied, as it was hoped they would do, in opposition to the Mahdi, whose armies had gradually advanced and had besieged the city. General Gordon with the troops there had made expeditions up the river in the steamers, and brought in provisions for the besieged town; he had fought several battles with the Mahdists, in which he had not always been successful, and it was known that unless help arrived the city must finally surrender. Many letters had been received from him asking urgently for aid, but weeks and months passed, and the government who had sent him out were unable to make up their minds to incur the cost necessary for the despatch of so distant an expedition.

In Cairo public feeling ran very high, and among the troops there the indignation at this base desertion of one of England's noblest soldiers was intense and general. At last the news came that public feeling in England had become so strong that government could no longer resist it, and that orders had been issued to prepare an expedition with all haste. A number of flat-boats were to be built for conveying the troops up the Nile. Canadian boatmen had been sent for to aid in the navigation of the river. Camels were to be purchased in Egypt, a mounted infantry corps organized, and stores of all kinds hastily collected.

People who knew the river shook their heads, and said that the decision had been delayed too long. The Nile would have fallen to a point so low that it would be difficult if not impossible to pass up the cataracts, and long before help could reach Khartoum the city and its noble governor would have fallen into the hands of the Mahdi.

There was much disgust among the troops when it was known that many of them would remain in Lower Egypt, and that of the cavalry especially but a very small force would be taken, while three regiments mounted on camels, two of them consisting of cavalry men from England, would take part in the expedition.

Some of the soldiers, however, looked at the matter more philosophically. "We have had our share," they argued, "and if the Mahdi's men fight as well as Osman Digma's we are quite willing that others should have their whack. There will be no end of hard work, and what fighting they get won't be all one way. Sand and heat, and preserved meat and dirty water out of wells, are not very pleasant when you have to stick to them for months together. Like enough, too, there will be another rumpus down at Suakim while the expedition is away, and then those who are left here now will get some more of it."

But although these arguments were loudly uttered, there was no doubt that there was considerable soreness, and that the men felt the hardship of favoured troops from England being employed in their stead in a service that, if dangerous, was likely to offer abundant opportunities for the display of courage and for gaining credit and honour.

CHAPTER IX.

THE CAMEL CORPS

"Trumpeter Smith! Trumpeter Smith!" The shout ran through the arched corridor of the barracks, and a soldier putting his head through one of the windows repeated the cry at the top of his voice, for Trumpeter Smith was not in his barrack-room. Edgar, in fact, was walking on the shady side of the great court-yard chatting with two other troopers when his name was shouted.

"Hullo! What is it?"

"You are to go to Major Horsley's quarters."

Edgar buttoned up his jacket, ran to the washing-place, plunged his head and hands in water and hastily dried them, smoothed down his hair with his pocket-comb at a piece of looking-glass that had been stuck up against the wall above the basins, and adjusting his cap to the correct angle made his way to Major Horsley's quarters, wondering much what he could be wanted for, but supposing that he was to be sent on some message into the town.

The soldier-servant showed him into the room where Major Horsley and his wife were sitting.

After a word or two of kindly greeting from the lady, Major Horsley went on: "I told you a long time back, Smith, that I should not forget the service you did my wife and her sister, and that I would do you a good turn if I ever got the chance. Is there anything you particularly want at present?"

"No, sir, except that I have been thinking that I should be glad to give up my trumpet. I am just eighteen now, and it would be better for me, I think, to take my regular place in the ranks. I should be more likely to be promoted there than I am as a trumpeter."

"Yes, you would be sergeant in a very short time, Smith; after your behaviour at El-Teb you would be sure of your stripes as soon as you were eligible for them. But I should not advise you to give up your trumpet just at the present moment."

"Very well, sir," Edgar said, somewhat surprised.

"But there is something else you are wishing for, is there not? I fancy every officer and man in the regiment is wishing for it."

"To go up the Nile, sir?" Edgar said eagerly. "Yes; I do wish that, indeed. Is there any chance of the regiment going, sir?"

"No, I am sorry to say there is not," the major said.

"And a very good thing too, Richard," his wife put in.

"I do not think so at all. It is the hardest thing ever heard of that the regiments here that have had all the heat and hard work, and everything else of this beastly place, are to be left behind, while fellows from England go on. Well, Smith," he went on, turning to Edgar, "I am glad to say I have been able to do you a good turn. When I was in the orderly-room just now a letter came to the colonel from the general, saying that a trumpeter of the Heavy Camel Corps is down with sunstroke and will not be able to go, and requesting him to detail a trumpeter to take his place. I at once seized the opportunity and begged that you might be chosen, saying that I owed you a good turn for your plucky conduct at Aldershot. The adjutant, I am glad to say, backed me up, saying that you have done a lot of credit to the regiment with your cricket, and that the affair at El-Teb alone ought to single you out when there was a chance like this going. The colonel rather thought that you were too young, but we urged that as you had stood the climate at Suakim you could stand it anywhere on the face of the globe. So you are to go, and the whole regiment will envy you."

"I am obliged to you indeed, sir," Edgar said in delight. "I do not know how to thank you, sir."

"I do not want any thanks, Smith, for a service that has cost me nothing. Now you are to go straight to Sergeant Edmonds. I have sent him a note already, and he is to set the tailors at work at once to rig you out in the karkee uniform. We cannot get you the helmet they are fitted out with. But no doubt they have got a spare one or two; probably they will let you have the helmet of the man whose place you are to take. You will be in orders to-morrow morning, and I have asked Edmonds to get your things all finished by that time. Come in and say good-bye before you start in the morning."

There was no slight feeling of envy when Edgar's good fortune became known, and the other trumpeters were unanimous in declaring that it was a shame his being chosen.

"Well, you see, you could not all go," the trumpet-major said, "and if Smith had not been chosen it would have been long odds against each of you."

"But he is the last joined of the lot," one of the men urged.

"He can blow a trumpet as well as any of you," the sergeant said, "and that is what he is wanted for. I think that it is natural enough the colonel should give him the pull. The officers think a good deal of a fellow who helped the regiment to win a dozen matches at cricket, and who carried off the long-distance running prize at Aldershot; besides, he behaved uncommonly well in that fight, and has as good a right to the V.C. as any man there. I think that a fellow like that ought to have the pull if only one is to get it, and I am sure the whole regiment will be of opinion that he has deserved the chance he has got."

By the next morning the suit of karkee was ready, and Edgar was sent for early to the orderly-room and officially informed by the colonel that he had been detailed for service in the Heavy Camel Corps.

"I need not tell you, Smith, to behave yourself well—to be a credit to the regiment. I should not have chosen you for the service unless I felt perfectly confident that you would do that. I hope that you will come back again safe and sound with the regiment. Good-bye, lad!"

Edgar saluted and left the room. Several of the officers followed him out and bade him a cheery farewell, for he was a general favourite. All knew that he was a gentleman, and hoped that he would some day win a commission. He then accompanied Major Horsley to his quarters, and there the officer and his wife both shook hands with him warmly.

"You will be a sergeant three months after you come back," Major Horsley said; "and your having been on this Nile expedition, and your conduct at El-Teb, will help you on when the time comes, and I hope you will be one of us before many years are over."

Edgar then went up to his barrack-room to say good-bye to his friends, and took off his smart Hussar uniform and put on the karkee suit, amid much laughter and friendly chaff at the change in his appearance. The adjutant had ordered a trooper to accompany him to the camp of the Camel Corps, which was pitched close by the Pyramids, and to bring back his horse. He therefore mounted and rode out of the barracks, amid many a friendly farewell from his comrades. He rode with his companion into the town and down to the river, crossed in a ferry-boat, and then rode on to the camp. Inquiring for the adjutant's tent Edgar dismounted and walked up to that officer, and presented a note from the colonel.

The officer glanced at it. "Oh, you have come to accompany us!" he said. "You look very young for the work, lad; but I suppose your colonel would not have chosen you unless he thought you could stand it. I see you have got our uniform, but you want a helmet. We can manage that for you. Sergeant Jepherson, see if Trumpeter Johnson's helmet will fit this man; he is going with us in his place. Fit him out with water-bottle and accoutrements, and tell him off to a tent."

The helmet fitted fairly, and only needed a little padding to suit Edgar, who, after putting it on, ran out to where his comrade was waiting for him and fastened his own head-gear to the pummel of his saddle.

"Good-bye, young un!" the trooper said. "Hold your own with these heavies for the honour of the regiment. They mean well, you know, so don't be too hard upon them."

Edgar laughed as he shook the man by the hand, and as he rode off turned to look at the scene around him.

There were two camps at a short distance from each other, that of the Heavy Camel Corps to which he now belonged, composed of men of the 1st and 2d Life Guards, Blues, Bays, 4th and 5th Dragoon Guards, Royals, Scots Greys, 5th and 16th Lancers. The other was the Guards Corps, composed of men of the three regiments of foot guards. Edgar's first feeling as he looked at the men who were standing about or lying in the shade of the little triangular Indian mountain-service tents, was that he had suddenly grown smaller. He was fully up to the average height of the men of his own regiment, but he felt small indeed by the side of the big men of the heavy cavalry regiments.

"This way, lad," the sergeant into whose charge he had been given, said. "What is your name?"

"I am down as Ned Smith."

The sergeant smiled at the answer, for no inconsiderable number of men enlist under false names. He led the way through the little tents until he stopped before one where a tall soldier was lying at full length on the sand. "Willcox, this man has come to take the place of Trumpeter Johnson. He is detached for duty with us from the Hussars. He will, of course, share your tent."

"All right, sergeant! I will put him up to the ropes. What's your name, mate?"

"I go as Ned Smith," Edgar said.

"So you are going in for being a heavy at present."

"I don't care whether I am a heavy or a light, so that I can go up the river."

"Have you been out here long?"

"About a year; we were through the fighting at Suakim, you know. It was pretty hot down there, I can tell you."

"It is hot enough here for me—a good deal too hot, in fact; and as for the dust, it is awful!"

"Yes, it is pretty dusty out here," Edgar agreed; "and of course, with these little tents, the wind and dust sweep right through them. Over there in Cairo we have comfortable barracks, and as we keep close during the day we don't feel the heat. Besides, it is getting cooler now. In August it was really hot for a bit even there."

"Where are we going to get these camels, do you know?"

"Up the river at Assouan, I believe; but I don't know very much about it. It was only yesterday afternoon I got orders that I was to go with you, to take the place of one of your men who had fallen sick, so I have not paid much attention as to what was going on. It has been rather a sore subject with us, you see. It did seem very hard that the regiments here that have stood the heat and dust of this climate all along should be left behind now that there is something exciting to do, and that fresh troops from England should go up."

"Well, I should not like it myself, lad. Still I am precious glad I got the chance. I am one of the 5th Dragoon Guards, and you know we don't take a turn of foreign service—though why we shouldn't I am sure I don't know—and we are precious glad to get a change from Aldershot and Birmingham and Brighton, and all those home stations. You are a lot younger than any of us here. The orders were that no one under twenty-two was to come."

"So I heard; but of course as we are out here, and we have got accustomed to it, age makes no difference."

"What do they send us out here for?"

"There are no barracks empty in the town, no open spaces where you could be comfortably encamped nearer. Besides, this gives you the chance of seeing the Pyramids."

"It is a big lump of stone, isn't it?" Willcox said, staring at the Great Pyramid. "The chaps who built that must have been very hard up for a job. When I first saw it I was downright disappointed. Of course I had heard a lot about it, and when we got here it wasn't half as big as I expected. After we had pitched our tents and got straight, two or three of us thought we would climb up to the top, as we had half an hour to spare. Just as we set off one of the officers came along and said, 'Where are you going, lads?' and I said, 'The cooks won't have tea ready for half an hour, sir, so we thought we would just get up to the top and look round.' And he said, 'If you do you will be late for tea.'

"Well, it didn't seem to us as if it would take more than five minutes to get to the top and as much to get down again, so off we went. But directly we began to climb we found the job was not as easy as we had expected. It looked to us as if there was but a hundred steps to go up; but each step turned out to be about five feet high, and we hadn't got up above twenty of them when the trumpet sounded, and we pretty near broke our necks in coming down again. After that I got more respect for that lump of stone. Most of the officers went up next day, and a few of us did manage it, but I wasn't one of them. I did try again; but I concluded that if I wanted to go up the Nile, and to be of any good when I got there, I had best give it up, for there would not be anything left of me to speak of by the time I got to the top. Then those Arab fellows got round, and shrieked and jabbered and wanted to pull us up; and the way they go up and down those stones is wonderful. But of course they have no weight to carry. No, I never should try that job again, not if we were to be camped here for the next ten years."