Полная версия

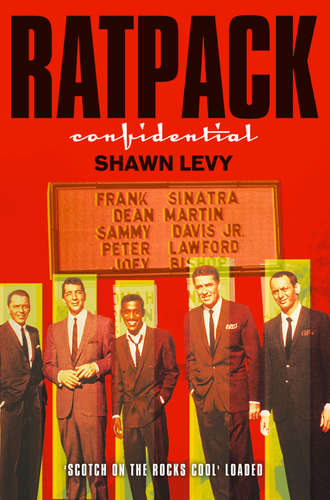

Rat Pack Confidential

As a member of the Dorsey orchestra, Frank became famous: hit records, magazine covers, appearances in movies, flattering press. Like he’d learned from Dolly, he milked it, aggressively courting the press, disc jockeys, anyone he thought could boost his career. He spent more than he earned on his wardrobe alone (he was so finicky about his personal cleanliness that his bandmates with Dorsey nicknamed him Lady Macbeth). Within three years, he was convinced that Dorsey was holding him back from a career that would rival Crosby’s, and he left—after months of bitter, petty infighting, a lucrative settlement, and a grudging goodbye.

Suddenly, everything: Frank signed to play the Paramount Theater in Times Square as an “extra added attraction” with the popular Benny Goodman orchestra; when Goodman introduced Frank, the response from the packed theater was so volcanic that he asked his band, “What the fuck was that?” Within a few months, the whole world would know. Spontaneously, Frank had become the beloved of a generation of wild-eyed fans—young girls, mostly—who made him a teen idol decades before anyone ever thought to manufacture such a thing.

Boosted by the devilishly clever press agent George Evans, Frank became bigger than Crosby or Vallee or Caruso—the biggest thing ever in showbiz, in fact. There was a core of critics and musicians among the cognoscenti who admired his artistry (James Agee spoke fondly of his “weird, fleeting resemblances to Lincoln”), but the wellspring was the kids—the bobby-soxers, as they were named for an affectation of footwear. Sinatratics they called themselves, forming cultish cells in devotion to their new god: the Slaves of Sinatra, the Sighing Society of Sinatra Swooners, the Flatbush Girls Who Would Lay Down Their Lives for Frank Sinatra, the Frank Sinatra Fan and Mahjong Club.

These daughters of flappers were quick to connect the longing in Frank’s voice with their own longings, his quavery presence with the absent boys who were off fighting the Hun and the Nip (Frank was 4-F: punctured eardrum). Odd as it may have seemed to everyone in the business, the wiseass runt with the heavenly voice was some kind of sex symbol. (And he’d always be one: For a half-century, Frank was one of the ways America made love, quite often the most popular; he was able to get away with anything because he hit people in their most personal spots.)

By the late fifties, by Rat Pack time, when his audience had grown up, Frank could be as sexy as he felt, but in the first blush of his fame, he had, like all teen idols, to be officially Off Limits. Conveniently, he had a cozy domestic life to play up: He’d been married to a girl-next-door type since 1939; by 1944, they had two kids, one named after each of them: Little Nancy and Frankie Jr.

For George Evans—and for Frank’s many important employers: Columbia Records, CBS radio, MGM, Lucky Strike—this was a perfect setup: a talented, massively popular young guy with a solid family and a wholesome aspect. But Frank seemed hell-bent on screwing it up. There was that entourage—big, unlikely guys, boxing writers, gamblers, songwriters buttering him up—and there were women and there was this habit of snapping back at the press and there was all the politics: Bad enough he was 4-F; did he have to sing “Ol’ Man River” and break bread with Eleanor Roosevelt? Evans spent the better part of the forties covering Frank’s ass, cozying up to some columnists and scratching and clawing at others while his client carried on however he pleased, simply assuming that somebody else would sweep it up.

He rose to insane heights. In 1939, he was waiting tables at the Rustic Cabin for $15 a week; by the end of the war, he was a bigger star in more media than anyone in the world and had grossed an estimated $11 million. By sheer earnings standards, he was probably the biggest star ever, anywhere; it almost didn’t matter that he was an artistic genius with more pure vocal talent than virtually anyone who’d ever been recorded.

Still and all, he was a creature of the popular culture and, as such, subject to the public’s whimsies. As the forties closed, talk leaked into the press about ties to communism and mobsters, there were ugly spats with writers, photographers, waiters, carhops, fans. His once-promising film career had sputtered—The Kissing Bandit, anyone?—and, after Frank made a wisecrack about one of Louis B. Mayer’s mistresses, MGM gave him his release. On the radio, he was bumped down from Your Hit Parade to a fifteen-minute, B-level show; on TV, CBS just plain dumped him.

He had trouble with his voice—he opened his mouth once at the Copa and couldn’t make a sound come out—and he seemed, further, to have lost his aesthetic way, letting Columbia’s new A&R man, Mitch Miller, talk him into making horseshit records with arrangements scaled wrong for his voice and dog barks thrown in as comic relief. The pathetic fall seemed poetically complete in 1952 when he returned to the Paramount Theater in support of a film of his own (the forgettable Meet Danny Wilson) and couldn’t even fill the balcony, much less stop traffic in Times Square.

Frank had gone from “extra added attraction” to King of the Universe in a couple of years; then, in about the same time span, he couldn’t get a job—and not a few people in the business were glad of it. With his ambition, quick temper, and iconoclasm, he’d done a lot of pissing off in his decade on the scene. His reputation was poison: When Capitol Records president Alan Livingston told his staff that he’d signed Sinatra at terms very favorable to the company, they groaned as one.

Presaging all of this calamity, turning the bobby-soxers against him and making him look like some pathetic pussy-whipped Milquetoast, was his wanton affair with Ava Gardner. Frank had never been faithful to Nancy in even a loose sense of the word, but, like many showbiz wives, she seemed willing to put up with peccadilloes even with such hot numbers as Marilyn Maxwell and Lana Turner. But this thing with Ava was more passionate and public than any of his other dalliances; it might have begun as a meaningless Hollywood fling, but they carried on all over the country throughout 1949, and Frank’s cardboard marriage finally became untenable. In the spring of 1950, he left the pretty Italian girl and the three cute kids that were his P.R. chastity belt. George Evans, enervated and skinny to begin with, bald from defending him, up and died one night after arguing with a columnist about Frank and Ava; he was forty-eight, and his heart had given out.

The affair and subsequent marriage were absurdly tempestuous and about as private as a presidential campaign; Ava was a lioness and Frank was her plaything. She was as promiscuous, lustful, hard-drinking, and profane as he was, and she had the hooks into him but good. She busted his balls mercilessly, running off with bullfighters and making him look like an ass in front of the world. He threatened suicide several times and took two stabs at it—once in Lake Tahoe with pills, once in New York with a razor. His disgrace and comeuppance were complete: Not only was he a has-been as a singer, an actor, and a performer, he was a flop as a cocksman. He was a joke: last year’s punch line.

When he finally managed to crawl out of his hole, then, it was all the more resoundingly triumphant. He achieved it in part through a movie role—Maggio, the pip-squeak private who died horribly at the hands of a bullying sergeant in From Here to Eternity. Throughout the latter half of 1952, Frank campaigned actively with Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn to get the part, and Cohn’s relationship with the Chicago Outfit’s West Coast point man, Johnny Rosselli, assured Frank at least a hearing. He got the job, he did really good in it, he got the Oscar, poof: He was all better. Once considered an overweening interloper in Hollywood, he was suddenly in the spring of ’54 a resilient, dues-paying member of the acting club. He had done the good thing; he had died for his fame and resurrected himself. He made more movies and he had hit after hit; he was even good in some of them.

At the same time, he took a new turn musically. No longer was he the reed-thin, warbling young crooner with a voice like a viola and a closet full of floppy bow ties. Now working for Capitol Records, he was more propulsive and dynamic, his voice richer and deeper—a cello. He was wearing fedoras and stylish suits; he was singing up-tempo about swinging and in dramatic, elegiac tempi about loss.

As in the movies, he seemed to have earned the right to his station; what’s more, as a singer, he expanded the very art form. He cut whole albums of songs built on the same musical ideas—saloon songs, swing numbers, waltzes—and even lyrical ideas: flying, dancing, the moon. Through the decade, he made the greatest pop records in history—one after another, sometimes as many as four a year.

Come 1959, he could look back twenty years and see a punk kid with nothing but ambition to his credit, he could look back a decade and see a big star dumped by the world, or he could look into the mirror and see the most influential and talented popular entertainer of the century.

Now what?

Frank was to become such a colossus of American popular culture that it would’ve been crazy in his heyday to think of him as needy. But his heroic Last Honest Man posture always had as a counterpart a little boy’s thirst for camaraderie and love. “I don’t think Frank’s an adult emotionally,” his friend Humphrey Bogart sniffed. Shirley MacLaine was more clinical, calling Sinatra “a perpetual performing child who wants to please the mother audience.”

Never mind all the gruff stuff offstage: The evidence of what was in his heart was in his art. Here was a man who lived amid an entourage that could expand, if he wished it to, to infinity, a man who had virtually every woman he ever desired, a man for whom no material comfort was unattainable; yet his music was at its richest and most intense when he sang piteously about loneliness. His familiar swinging cockiness would be overwhelmed by a gray, anguished fog hovering over a profound, hollow core—the achy soul of the Tender Tough. “I’ll Be Seeing You,” “These Foolish Things,” “Guess I’ll Hang My Tears out to Dry,” “In the Wee Small Hours,” “Angel Eyes,” “What’s New?,” “One for My Baby”—a world of crushed dreams, blasted hopes, distant, impossible romance. People called it suicide music and couldn’t understand why he slowed down every show to perform it—sometimes exclusively. But loneliness was the most vibrant color in his musical palette, and it obviously came from someplace very deep inside of him.

Indeed, he was born to it. He was, of course, an only child—try to name another Italo-American only child of his generation!—and grew up with a yearning for the companionship that his friends, neighbors, and cousins all enjoyed in their homes. The cash and clothing that his mother lavished on him were his first means of acquiring a society: He handed down suits to kids whose friendship he courted; he bought burgers and candy and comic books, cultivating early on a habit of “gifting”—treating the house to drinks or meals or clothes or women or more. The assets Dolly spotted him as a teenager—his wardrobe, his car, his sheet music arrangements, his portable sound system—they were a way for him to get a leg up in show business, true, but they were also a means of being part of a bigger group.

Which is what made it so perfect that Sinatra came into his own as a performer during the big band era, when a singer was by necessity a piece of a large, vibrant whole. The Harry James and Tommy Dorsey bands were like big clubs of chums for him—and he didn’t have to buy his way in, either. He gorged himself on the grand bonhomie that the bands instantly provided him—the card games, hazing, drinking, dreaming, and bonding that he and his fellow musicians engaged in during endless bus rides. He was like a congenital junkie who became addicted with his very first hit. As soon as he’d begun life in that dazzling musical fraternity, he wanted to live no other way.

Witness his recollection of the day on which he left James for Dorsey: January 1940, Buffalo; the James band was headed to Hartford; Frank would briefly visit New York, then join Dorsey in Rockford, Illinois; it was the single big break of his career, and he’d yearned for it and schemed to make it so; still, he struggled through the separation from his bandmates of a mere six months: “The bus pulled out with the rest of the boys at about half-past midnight. I’d said good-bye to them all, and it was snowing, I remember. There was nobody around and I stood alone with my suitcase in the snow and watched the taillights disappear. Then the tears started and I tried to run after the bus.” (This was, keep in mind, a married man with a child on the way.)

Of course, the Dorsey band was to offer Frank the same sort of companionship he enjoyed with James. Moreover, Dorsey himself would come to serve as a hero and model for his young singer; Frank dressed and spoke like him, he studied his famous breathing technique, he even took up his hobby of model railroading. Still, even with the prospect of a new gang of buddies assured him, he arrived in Illinois with the beginnings of his own coterie, a safeguard against ever finding himself staring longingly at the receding taillights of a bus again: Nick Sevano, a Hoboken haberdasher who dressed him, did his errands, and even lived with him and his family when they weren’t on the road, and Hank Sanicola, accompanist, business manager, and, as his girth suggested, sometime thumbbreaker.

Two years later, when the allure of profits and aesthetic freedom drove Sinatra to seek his release from the Dorsey band, he was, once again, bereft of bandmates, so he gathered to his bony bosom a band, of sorts, of his own. He expanded his entourage to include such semiregulars as Mannie Sachs, a Columbia Records executive; Ben Barton, his music publisher and business partner; composer Jimmy Van Heusen; lyricist Sammy Cahn; bruisers Tami Mauriello and Al Silvani; and Jimmy Taratino, a boxing writer whose mob ties eventually formed a costly web for the singer. And he gave them all, guilelessly, a name: the Varsity.

En masse, the Varsity hit all the swell spots—nightclubs, saloons, showbiz eateries, and, especially, the Friday night fights at Madison Square Garden, where they mingled with mobsters, Times Square sharpies, and other supernumeraries of the fight game. Grown men actually vied to be admitted to their numbers, but that privilege was rarely granted, and the resultant loyalty of its members was embarrassingly high: When Mauriello was inducted into the service and sent overseas to fight, he gave Frank his golden ID bracelet, which the singer wore with puppy-dog pride.

After the war, the Varsity evolved, with some members resuming their lives without Frank (not always peaceably or voluntarily) and others accompanying him out West, where he had joined the extended family of MGM studios. There was a Softball team—Sinatra’s Swooners, with uniforms and cheerleaders (and Ava Gardner as, ahem, honorary bat girl); there were card games, pub crawls, the works.

But then the spiral that demolished his career began: Divorced, his voice uncertain, his name connected with reds, hoods, and a dozen drunken little fistfights, without a record company, film contract, or agent to call his own, he suddenly didn’t seem like a Sun King anymore. A few steadfast partisans held on; the larger crowd vaporized.

It was a subtle thing: People didn’t so much snub Frank as stop courting him. He couldn’t get tables in the same restaurants, or not the same tables, anyway. He couldn’t round up a poker game or gang of drunks to obliterate a night with him. Early one morning at the dawn of the fifties, Sammy was walking through Times Square, overjoyed with just having been allowed to break the color barrier long enough to schmooze with the big stars at Lindy’s. He passed the Capitol Theater—the place where Frank had once hired him and his dad and uncle when they were still unknown—and lo, there Frank was, walking along with a wounded air.

“Not a soul was paying attention to him,” Sammy recalled later. “This was the man who only a few years ago had tied up traffic all over Times Square. Thousands of people had been stepping all over each other trying to get a look at him. Now the same man was walking down the same street and nobody gave a damn.”

For Sammy, to whom the clubbiness and fame of showbiz were brass rings worth one’s very soul, it was a stunning sight. “I couldn’t take my eyes off him, walking the streets alone, an ordinary Joe who’d been a giant. He was fighting to make it back again but he was doing that by himself, too. The ‘friends’ were gone with all the presents and the money he’d given them. Nobody was helping him.”

There were others who sensed Sinatra’s pain and tried to help. L.A. gangster Mickey Cohen, an admirer of the singer’s (“If you call Frank’s hole card,” he said approvingly, “he’s gonna answer”), tried to rally his spirits by hosting a testimonial dinner for him at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Instead, the sparsely attended event simply underscored Sinatra’s dilemma. As Cohen recalled in his hilarious autobiography, “A lot of people that were invited to that Sinatra testimonial, that should have attended but didn’t, would bust their nuts in this day to attend a Sinatra testimonial. A lot of them would now kiss Frank’s ass after he made the comeback, but they didn’t show up when he really needed them. I don’t know the names of a lot of them bastards in that ilk of life, but I remember the people that I had running the affair at the time telling me, Jesus, this and that dirty son of a bitch should have been here.”

At the time, Frank wasn’t really keeping up with all the snubs—he was far too bewildered by life with Ava and the prospect of resuscitating his career. But he was still Dolly’s boy, and he had to have noticed the slights. And if he’d ever shown himself to be curt and exclusive before bottoming out and being left behind, when he recovered he became more demanding than ever of the loyalty of those he allowed around him. Only the surest would be abided.

Such a one was Humphrey Bogart, the movie god whose blessing upon Frank was one of the lifelines that kept him hopeful that he might someday emerge from the straits in which fate had left him foundering.

In all Hollywood, nobody had a flintier or more enviable reputation than Bogart. An Upper West Side sissy boy who went from playing juvenile walk-ons to psychotic killers, paranoid adventurers, and cynics with soft hearts, he danced just within the boundaries of the game. His drinking, womanizing, and bellicosity never quite made the front pages, his bad-mouthing of bosses never quite stooped to insubordination, and his liberal political beliefs and headstrong independence never quite severed him from the basis of his wealth, fame, and popularity. The one potential faux pas of his life—his affair with starlet Lauren Bacall—was easily cast by studio flacks and gossip mavens as a great May – December romance, especially after the couple wed and started a family.

For a large part of the movie colony, Bogie was a cult hero—a Knight of the True Way. He did his work best by being something that no one else could be: himself. Off-camera, he drank away afternoons in restaurants, went out of his way to upset prigs at parties, cruised the Pacific on his sailboat, and made, with his young wife, a home that offered haven to those very select few in his business who, like him, weren’t fooled for a minute by their own press.

Nothing, but nothing, rattled Bogart more than the sight of Hollywood kissing its own behind, especially over unproven new talent, and especially unproven male talent that was rooted in alleged sex appeal. So in 1945, when the jug-eared boy singer who made the bobby-soxers wet their pants showed up in town to great foofaraw, Bogart was ready to dismiss him out of hand. They ran into one another for the first time at the Players, the Sunset Boulevard restaurant, bar, and theater owned by Preston Sturges.

“They tell me you have a voice that makes girls faint,” said Bogart, an expert needler. “Make me faint.”

Sinatra stood right up to him: “I’m taking the week off.”

Bogart liked the response, liked the kid. And Frank, of course, saw in Bogart all the things he always wanted to be: aloof, profound, world-weary, slightly drunk, slightly sentimental, romantic, tender, tough, loyal, and proud. (He could take his hero worship too far. Once, when a date of Frank’s declared, in Bogart’s presence, “You sound like Bogie sometimes,” the actor laughed and said, “Don’t remind him, sweetheart, the poor bastard’s trying to kick it!”) He tried to cajole producers into casting him in Knock on Any Door as a tough street kid opposite Bogart’s impassioned lawyer; such was Sinatra’s stock as an actor that the role went to John Derek.

Nevertheless, the two men got into the habit of spending time together whenever the occasion arose, which, given Frank’s hectic schedule of filmmaking, recording, and touring, wasn’t often. In 1949, though, Frank moved his family from Toluca Lake to Holmby Hills, just blocks from Bogart’s house. This new proximity allowed the two stars more frequent contact; soon after moving into the neighborhood, Sinatra organized a guys-only baby shower for Bogart when Lauren Bacall was pregnant with their first child.

The relationship got a little strange. After Frank had left Nancy and the kids, he was still welcome in their house; he would frequently crash on his estranged wife’s couch after nights of bingeing with Bogart, shuttling between the two homes as if, in his mind, they constituted one. “He’s always here,” Bogart told a reporter. “I think we’re parent substitutes for him, or something.” Bacall empathized with Frank’s need for companionship, but Bogart warned her against getting wrapped up in it. “He chose to live the way he’s living—alone,” he admonished his wife. “It’s too bad if he’s lonely, but that’s his choice. We have our own road to travel, never forget that—we can’t live his life.”

In fact, Bogart was one of the few people who were willing to tell Frank exactly what they thought of some of the things he did. There was the time he hosted Sinatra, David Niven, and Richard Burton for a night of drinking on his beloved yacht, Santana. Frank was at a career ebb, and he passed part of the night on deck, serenading yachters on the other boats moored nearby; Bogie grew so irate with Sinatra’s preening performance, recalled Burton, that he and Frank “nearly came to blows.”

There was the time when Frank, riding high on the early reviews for From Here to Eternity, visited his hero in search of approval. “I saw your picture,” said Bogie. “What did you think?” Frank asked. Bogart simply shook his head no.

And there was Bogart’s famous line about Frank’s thin-skinned egoism: “Sinatra’s idea of paradise is a place where there are plenty of women and no newspapermen. He doesn’t know it, but he’d be better off if it were the other way around.”

Still, there was a bond between the two: father-son, mentor-acolyte, king-pretender—somehow the dynamic was agreeable to them both. They both reviled the traditional cant and decorum of Hollywood protocol, they both had deep political concerns for the everyman, and they both loved to needle people, especially the thin-skinned twits their lives as famous performers gave them so many chances to meet. Frank was always welcome in the Bogart home; the Bogarts, in turn, accepted his hospitality when he would want to scoop up a gang of pals and run off for a weekend in the Springs or Vegas.

In June 1955, for instance, he gathered a dozen or so chums, rented a train, and took off to catch Noel Coward’s opening at the Desert Inn (yes, that Noel Coward and that Desert Inn; Vegas was always great with novelties). During that particular spree, legend has it, the group had gotten so deep into its cups that Bacall was startled by their debauched appearance when she caught a gander of them ringside in a casino showroom. She looked around at all the famous flesh—Frank; Bogart; Judy Garland; David Niven; restaurateur Mike Romanoff; literary agent Swifty Lazar and his date, Martha Hyer; Jimmy Van Heusen and his date, Angie Dickinson; a few well-oiled others.