полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 189, June 11, 1853

These curious materials for history are in the rough and confused state in which they were left by their author, and, to render them available, would require an index to the whole.

The "Remembrances" are in some degree illustrated by Harl. MS. 604., which is a very curious volume of monastic affairs at the dissolution. Also by 605, 606, and 607. The last two belong to the reign of Philip and Mary, and contain an official account of the lands sold by them belonging to the crown in the third and fourth years of their reign.

E. G. Ballard.The Royal Garden at Holyrood Palace.—I cannot help noticing a disgraceful fact, which has only lately come to my knowledge. There is, adjoining the Palace of Holyrood, an ancient garden of the old kings of Scotland: in it is a curious sundial, with Queen Mary's name on it. There is a pear-tree planted by her hands, and there are many other deeply interesting traces of the royal race, who little dreamed how their old stately places were to be profaned, after they themselves were laid in the dust. The garden of the Royal Stuarts is now let to a market gardener! Are there no true-hearted Scotchmen left, who will redeem it from such desecration?

L. M. M. R.The Old Ship "Royal Escape."—The following extract from the Norwich Mercury of Aug. 21, 1819, under the head of "Yarmouth News," will probably be gratifying to your querist Anon, Vol. vii., p. 380.:

"On the 13th inst. put into this port (Yarmouth), having been grounded on the Barnard Sand, The Royal Escape, government hoy, with horses for his royal highness at Hanover. This vessel is the same that King Charles II. made his escape in from Brighthelmstone."

Joseph Davey.Queries

"THE LIGHT OF BRITTAINE."

I should be glad, through the medium of "N. & Q.," to be favoured with some particulars regarding this work, and its author, Maister Henry Lyte, of Lytescarie, Esq. He presented the said work with his own hand to "our late soveraigne queene and matchlesse mistresse, on the day when shee came, in royall manner, to Paule's Church." I shall also be glad of any information about his son, Maister Thomas Lyte, of Lytescarie, Esq., "a true immitator and heyre to his father's vertues," and who

"Presented to the Majestie of King James, (with) an excellent mappe or genealogicall table (contayning the bredth and circumference of twenty large sheets of paper), which he entitleth Brittaines Monarchy, approuing Brute's History, and the whole succession of this our nation, from the very original, with the just observation of al times, changes, and occasions therein happening. This worthy worke, having cost above seaven yeares labour, beside great charges and expense, his highnesse hath made very gracious acceptance of, and to witnesse the same, in court it hangeth in an especiall place of eminence. Pitty it is, that this phœnix (as yet) affordeth not a fellowe, or that from privacie it might not bee made more generall; but, as his Majestie has granted him priviledge, so, that the world might be woorthie to enjoy it, whereto, if friendship may prevaile, as he hath been already, so shall he be still as earnestly sollicited."

These two works appear to have been written towards the close of the sixteenth century. Is anything more known of them, and their respective authors?

Traja-Nova.Minor Queries

Thirteen an unlucky Number.—Is there not at Dantzic a clock, which at 12 admits, through a door, Christ and the Eleven, shutting out Judas, who is admitted at 1?

A. C.Quotations.—

"I saw a man, who saw a man, who said he saw the king."

Whence?

"Look not mournfully into the past; it comes not back again," &c.—Motto of Hyperion.

Whence?

A. A. D."Other-some" and "Unneath."—I do not recollect having ever seen these expressions, until reading Parnell's Fairy Tale. They occur in the following stanzas:

"But now, to please the fairy king,Full every deal they laugh and sing,And antic feats devise;Some wind and tumble like an ape,And other-some transmute their shapeIn Edwin's wondering eyes."Till one at last, that Robin hight,Renown'd for pinching maids by night,Has bent him up aloof;And full against the beam he flung,Where by the back the youth he hungTo sprawl unneath the roof."As the author professes the poem to be "in the ancient English style," are these words veritable ancient English? If so, some correspondent of "N. & Q." may perhaps be able to give instances of their recurrence.

Robert Wright.Newx, &c.—Can any of your readers give me the unde derivatur of the word newx, or noux, or knoux? It is a very old word, used for the last hundred years, as fag is at our public schools, for a young cadet at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. When I was there, some twenty-five or twenty-seven years ago, the noux was the youngest cadet of the four who slept in one room: and a precious life of it he led. But this, I hope, is altered now. I have often wanted to find out from whence this term is derived, and I suppose that your paper will find some among your numerous correspondents who will be able to enlighten me.

T. W. N.Malta.

"A Joabi Alloquio."—Who can explain the following, and point out its source? I copy from the work of a Lutheran divine, Conrad Dieteric, Analysis Evangeliorum, 1631, p. 188.:

"A Joabi Alloquio,A Thyestis Convivio,Ab Iscariotis 'Ave,'A Diasii 'Salve'Ab Herodis 'Redite'A Gallorum 'Venite.'Libera nos Domine."The fourth and sixth line I do not understand.

B. H. C.Illuminations.—When were illuminations in cities first introduced? Is there any allusion to them in classic authors?

Cape.Heraldic Queries.—Will some correspondent versed in heraldry answer me the following questions?

1. What is the origin and meaning of women of all ranks, except the sovereign, being now debarred from bearing their arms in shields, and having to bear them in lozenges? Formerly, all ladies of rank bore shields upon their seals, e.g. the seal of Margaret, Countess of Norfolk, who deceased A.D. 1399; and of Margaret, Countess of Richmond, and mother of Henry VIII., who deceased A.D. 1509. These shields are figured in the Glossary of Heraldry, pp. 285, 286.

2. Is it, heraldically speaking, wrong to inscribe the motto upon a circle (not a garter) or ribbon round the shield? So says the Glossary, p. 227. If wrong, on what principle?

3. Was it ever the custom in this country, as on the Continent to this day, for ecclesiastics to bear their arms in a circular or oval panel?—the martial form of the shield being considered inconsistent with their spiritual character. If so, when did the custom commence, and where may instances be seen either on monuments or in illustrated works?

Ceyrep.John's Spoils from Peterborough and Crowland.—Clement Spelman, in his Preface to the reader, with which he introduces his father's treatise De non temerandis Ecclesiis, says (edit. Oxford, 1841, p.45.):

"I cannot omit the sacrilege and punishment of King John, who in the seventeenth year of his reign, among other churches, rifled the abbeys of Peterborough and Croyland, and after attempts to carry his sacrilegious wealth from Lynn to Lincoln; but, passing the Washes, the earth in the midst of the waters opens her mouth (as for Korah and his company), and at once swallows up both carts, carriage, and horses, all his treasure, all his regalities, all his church spoil, and all the church spoilers; not one escapes to bring the king word," &c.

Is the precise spot known where this catastrophe occurred, or have any relics been since recovered to give evidence of the fact?

J. Sansom."Elementa sex," &c.—Perhaps one of your readers, given to such trifles, will hazard a guess at the solution, if not at the author, of the subjoined:

"Elementa sex me proferent totam tibi;Totam hanc, lucernis si tepent fungi, vides,Accisa senibus suppetit saltantibus,Levetur, armis adfremunt Horatii;Facienda res est omnibus, si fit minor,Es, quod relinquis deinde, si subtraxeris;Si rite tandem quæritas originem,Ad sibilum, vix ad sonum, reverteris."Effigy.Jack and Gill—Sir Hubbard de Hoy.—Having recently amused myself by a dive into old Tusser's Husbandrie, the following passages suggested themselves as fitting Queries for your pages:

Jack and Gill.—

"Let Jack nor GillFetch corn at will."Can the "Jack and Gill" of our nursery tales be traced to an earlier date than Tusser's time?

Hobble de Hoy.—Speaking of the periods of a man's life, Tusser's advice, from the age of fourteen years to twenty-one, is to "Keep under Sir Hubbard de Hoy." Is it known whether there ever existed a personage so named, either as a legend or a myth? And if not, what is the origin of the modern term "Hobble de Hoy" as a designation for a stripling? Bailey omits it in his Dictionary.

L. A. M.Humphrey Hawarden.—Information is solicited respecting this individual, who was a Doctor of Laws, and living in 1494. Also, of a Justice Port, living about the same period.

T. Hughes.Chester.

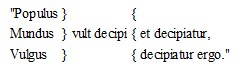

"Populus vult decipi."—

Who was the author of the maxim? which is its correct form? and where is it to be found? It seems to present another curious instance of our ignorance of things with which we are familiar. I have put the question to a dozen scholars, fellows of colleges, barristers, &c. &c., and none has been able to give me an answer. One only thinks it was a dictum of some Pope.

Harry Leroy Temple.Sheriffs of Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire.—Where can any list of the sheriffs for these counties be found, previous to the list given by Fuller from the time of Henry VIII.?

D.Harris.—The Rev. William Harris, B.A., was presented, by Thomas Pindar, Esq., to the vicarage of Luddington, Lincolnshire, on the 7th August, 1722. Mr. Harris died here in June, 1748, aged eighty-two. On his tomb is inscribed,—

"Illi satis licuitNunc veterum libris, nuncSomno, et inertibus horisDucere solicitæ jucunda oblivio vitæ."A tradition of his being a wizard still lingers in the village, and I should be very glad to receive any particulars respecting him. From an inspection of his will at Lincoln, it appears that he used the coat of the ancient family of Harris of Radford, Devon, and that his wife's name was Honora, a Christian name not infrequent about that period in families of the West of England also, as, for instance, Honora, daughter of Sir Richard Rogers of Bryanstone, who married Edward Lord Beauchamp, and had a daughter Honora, who married Sir Ferdinand Sutton; Honora, the wife of Harry Conway, Esq., of Bodrhyddan, Flint; Honora, daughter of Edward Fortescue of Fallapit; besides others.

W. H. Lammin.Fulham.

Replies

BISHOP BUTLER

(Vol. vii., p. 528.)"Charity thinketh no evil;" but we must feel both surprise and regret that any one should, in 1853, consider it a doubtful question whether Bishop Butler died in the communion of the Church of England. The bishop has now been in his grave more than a hundred years; but Warburton says truly, "How light a matter very often subjects the best-established characters to the suspicions of posterity—how ready is a remote age to catch at a low revived slander, which the times that brought it forth saw despised and forgotten almost in its birth."

X. Y. Z. says he would be glad to have this charge (originally brought forward in 1767) sifted. He will find that it has been sifted, and in the most full and satisfactory manner, by persons of no less distinction than Archbishop Secker and Bishop Halifax. The strong language employed by the archbishop, when refuting what he terms a "gross and scandalous falsehood," and when asserting the bishops "abhorrence of popery," need not here be quoted, as "N.& Q." is not the most proper channel for the discussion of theological subjects; but it is alleged that every man of sense and candour was convinced at the time that the charge should be retracted; and it must be a satisfaction to your correspondent to know, that as Bishop Butler lived so he died, in full communion with that Church, which he adorned equally by his matchless writings, sanctity of manners, and spotless life.4

J. H. Markland.Bath.

In reference to the Query by X. Y. Z., as to whether Bishop Butler died in the Roman Catholic communion, allow me to refer your correspondent to the contents of the letters from Dr. Forster and Bishop Benson to Secker, then Bishop of Oxford, concerning the last illness and death of the prelate in question, deposited at Lambeth amongst the private MSS. of Archbishop Seeker, "as negative arguments against the calumny of his dying a Papist."

Than the allegations that Butler died with a Roman Catholic book of devotion in his hand, and that the last person in whose company he was seen was a priest of that persuasion, nothing can be more unreasonable, if at least it be meant to deduce from these unproved statements that the bishop agreed with the one and held communion with the other. Dr. Forster, his chaplain, was with him at his death, which happened about 11 a.m., June 16; and this witness observes (in a letter to the Bishop of Oxford, June 18) that "the last four-and-twenty hours preceding which [i. e. his death] were divided between short broken slumbers, and intervals of a calm but disordered talk when awake." Again (letter to Ditto, June 17), Forster says that Bishop Butler, "when, for a day or two before his death, he had in a great measure lost the use of his faculties, was perpetually talking of writing to your lordship, though without seeming to have anything which, at least, he was at all capable of communicating to you." Bishop Benson writes to the Bishop of Oxford (June 12) that Butler's "attention to any one or anything is immediately lost and gone;" and, "my lord is incapable, not only of reading, but attending to anything read or said." And again, "his attention to anything is very little or none."

There was certainly an interval between this time (June 12) and "the last four-and-twenty hours" preceding his death, during which, writes Bishop Benson (June 17), Butler "said kind and affecting things more than I could bear." Yet, on the whole, I submit that these extracts, if fully weighed and considered with all the attending circumstances, contain enough of even positive evidence to refute conclusively the injurious suspicions alluded to by X. Y. Z., if such are still current.

J. R. C.MITIGATION OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT TO FORGERS

(Vol. iv., p. 434., &c.)I have asked many questions, and turned over many volumes and files of newspapers, to get at the real facts of the cases of mitigation stated in "N. & Q." Having winnowed the chaff as thoroughly as I could, I send the very few grains I have found. Those only who have searched annual registers, magazines, and journals for the foundation of stories defective in names and dates, will appreciate my difficulties.

I have not found any printed account of the "Jeannie Deans" case, "N. & Q.," Vol. iv., p. 434.; Vol. v., p. 444.; Vol. vi., p. 153. I have inquired of the older members of the Northern Circuit, and they never heard of it. Still a young man may have been convicted of forgery "about thirty-five years ago:" his sister may have presented a well-signed petition to the judges, and the sentence may have been commuted without the tradition surviving on the circuit. All however agree, that no man who ever sat on the bench deserved the imputation of "obduracy" less than Baron Graham. I should not have noticed the anecdote but for its mythic accompaniments, which I disposed of in "N. & Q.," Vol. v., p. 444.

In Vol. vi., p. 496., W. W. cites from Wade's British History:

"July 22, 1814. Admiral William B–y found guilty of forging letters to defraud the revenue. He was sentenced to death, which was commuted to banishment."

The case is reported in The Sun, July 25, 1814; and the subsequent facts are in The Times, July 30, and August 16 and 20. It was tried before Mr. Justice Dampier at the Winchester Summer Assizes. There were five bills against the prisoner for forgery, and one for a fraud. That on which he was convicted, was for defrauding the post-master of Gosport of 3l. 8s. 6d. He took to the post-office a packet of 114 letters, which he said were "ship letters," from the "Mary and Jane." He received the postage, and signed the receipt "W. Johnstone." The letters were fictitious. The case was fully proved, and he received sentence of death. He was respited for a fortnight, and afterwards during the pleasure of the Prince Regent. He was struck off the list of retired rear-admirals. It was proved at the trial, that, in 1809, he commanded "The Plantagenet;" but, from the unsettled state of his mind, the command had been given up to the first lieutenant, and that he was shortly after superseded. This, and the good character he received, were probably held to excuse the pardon.

I now come to the great case of George III. and Mr. Fawcett. I much regret that Whunside has not replied in your pages to my question (Vol. vii., p. 163.), as I could then have commented upon the facts, and his means of knowing them, with more freedom. I have a private communication from him, which is ample and candid. He objects to bring his name before the public, and I have no right to press that point. He is not quite certain as to the convict's name, but can procure it for me. He would rather that it should not be published, as it might give pain to a respectable family. Appreciating the objection, and having no use for it except to publish, I have declined to ask it of him.

The case occurred in 1802 or 1803, when Whunside was a pupil of Mr. Fawcett. He says:

"Occasionally Mr. Fawcett used to allow certain portions of a weekly newspaper to be read to the boys on a Saturday evening. This case was read to us, I think from the Leeds Mercury; and though Mr. Fawcett's name was not mentioned, we were all aware who the minister was."

Thus we have no direct evidence of the amount of Mr. Fawcett's communications with George III. How much of the story as it is now told was read to the boys, we do not know; but that it came to them first through a weekly paper, is rather against than for it.

We all know the tendency of good stories to pick up additions as they go. I have read that the first edition of the Life of Loyola was without miracles. This anecdote seems to have reached its full growth in 1823, in Pearson's Life of W. Hey, Esq., and probably in the two lives of George III., published after his death, and mentioned by Whunside. Pearson, as cited in "N. & Q.," Vol. vi., p. 276., says, that by some means the Essay on Anger had been recommended to the notice of George III., who would have made the author a bishop had he not been a dissenter; that he signified his wish to serve Mr. Fawcett, &c. That on the conviction of H–, Mr. Fawcett wrote to the king; and a letter soon arrived, conveying the welcome intelligence, "You may rest assured that his life is safe," &c.

It is not stated that this was "private and confidential:" if it was, Mr. Fawcett had no right to mention it; if it was not, he had no reason for concealing what was so much to his honour, and so extraordinary as the king's personal interference in a matter invariably left to the Secretary of State for the Home Department. If, however, Mr. Fawcett was silent from modesty, his biographers had no inducement to be so; yet, let us see how they state the case. The Account of the Life, Writings, and Ministry of the late Rev. John Fawcett: London, 1818, cited in "N. & Q.," Vol. vi., p. 229., says:

"He was induced, in conjunction with others, to solicit the exercise of royal clemency in mitigating the severity of that punishment which the law denounces: and it gladdened the sympathetic feelings of his heart to know that these petitions were not unavailing; but the modesty of his character made him regret the publicity which had been given to this subject."

The fifth edition of the Essay on Anger, printed for the Book Society for Promoting Religious Knowledge, London, no date, has a memoir of the author. The "incident" is said not to have been circulated in any publication by the family; but "it was one of the secrets which obtain a wider circulation from the reserve with which one relator invariably retails it to another." That is exactly my view. Secrecy contributes to diffusion, but not to accuracy. At the risk of being thought tedious, I must copy the rest of this statement:

"Soon after the publication of this treatise, the author took an opportunity of presenting a copy to our late much revered sovereign; whose ear was always accessible to merit, however obscure the individual in whom it was found. Contrary to the fate of most publications laid at the feet of royalty, it was diligently perused and admired; and a communication of this approbation was afterwards made known to the author. It happened some time afterwards, a relative of one of his friends was convicted of a capital crime, for which he was left for execution. Application was instantly made for an extension of royal favour in his behalf; and, among others, one was made by Mr. Fawcett: and his majesty, no doubt recollecting the pleasure he had derived from the perusal of his Essay on Anger, and believing that he would not recommend an improper person to royal favour, was most graciously pleased to answer the prayer of the petition; but as to precisely how far the name of Mr. Fawcett might have contributed to this successful application must await the great disclosures of a future judgment."

The reader will sift this jumble of inferences and facts, and perhaps will not go so far as to have "no doubt."

Whunside tells me, that about 1807 he employed a bookbinder from Halifax; who, on hearing that he had been a pupil of Mr. Fawcett, said he had seen two copies of the Essay on Anger, most beautifully bound, to be sent to the king.

The conclusion to which I come is, that Mr. Fawcett sent a copy of the Essay on Anger to the king; that the receipt of it was acknowledged, possibly in some way more complimentary than the ordinary circular; that a young man was convicted of forgery; that Mr. Fawcett and others petitioned for his pardon, and that he was pardoned. All the rest I hold to be mere rumours, not countenanced by Mr. Fawcett or his family, and not asserted by his biographers.

H. B. C.U. U. Club.

MYTHE VERSUS MYTH

(Vol. vii., p. 326.)Mr. Keightley's rule is only partially true, and in the part which is true is not fully stated. The following rules, qualified by the accompanying remarks, will I trust be found substantially correct.

English monosyllables, formed from Greek or Latin monosyllabic roots,

(1.) When the root ends in a single consonant preceded by a vowel, require the lengthening e.

(2.) When the root ends in a single consonant preceded by a diphthong, or in more than one consonant preceded by a vowel, reject the e.

1. Examples from the Greek:—σχῆμ-α, scheme; λύρ-α (lyr-a), lyre; ζών-η (zon-a), zon-e; βάσ-ις, base; φράσ-ις, phras-e; τρόπ-ος, trop-e. From Latin, ros-a, ros-e; fin-is, fin-e; fum-us, fum-e; pur-us, pur-e; grad-us, grad-e. Compare, in verbs, ced-o, ced-e.

Remarks.—This rule admits of a modification; e.g. we form from ζῆλ-ος zeal (the sound hardly perceptibly differing from zel-e); from ὥρ-α (hor-a), hour; from flos (flor-is), flower and flour (the long sound communicated to the vowel in the other words by the added e, being in these already contained in the diphthong). Add ven-a, vein; van-us, vain; sol-um, soil, &c.; and compare -ceed in proceed, succeed, formed from compounds of ced-o. Some, but not all, of these words have come to us through the French.