Полная версия

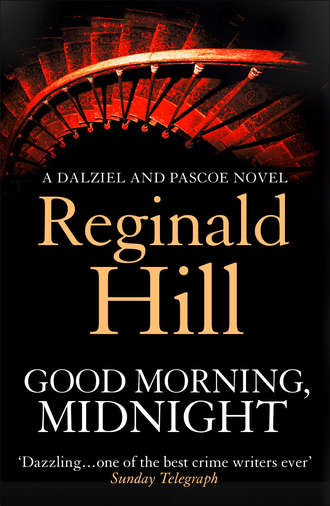

Good Morning, Midnight

He shivered, and this intrusion of meteorology bothered him like the name of the cottage. First the taste of food, now weather …

‘Do you live locally, Mr Hat?’ asked Waverley.

He had a gentle well-modulated voice with perhaps a faint Scots accent.

‘No,’ said Hat. ‘I got lost in the forest.’

‘The forest?’ echoed the man in a faintly puzzled tone.

‘I think Mr Hat means Blacklow Wood,’ said the witch with that nice smile.

‘Of course. And you’re quite right, Mr Hat. As you clearly know, this and one or two other little patches of woodland scattered around the area are all that remain of what used to be the great Blacklow Forest when the Plantagenets hunted here.’

Blacklow again. This time the vibration was strong enough to break the film of ice through which he viewed dreams and reality alike.

Now he remembered.

A dank autumn day … but his MG had been full of brightness as he drove deep into the heart of the Yorkshire countryside with the woman he loved by his side.

One of those small surviving patches of Blacklow Forest had been the copse out of which a deer had leapt, forcing him to bring his car to a skidding halt. Then he and she had pushed through the hedge and sat beneath a beech tree and drunk coffee and talked more freely and intimately than ever before. It had been a milestone in what had turned out to be far too short a journey.

Yesterday he’d driven out to the same spot and sat beneath the same tree, indifferent to the fall of darkness and the thickening mist. Nor when finally he rose and set off back to the car did he much care when he realized he’d missed his way. For an indeterminate period of time he’d wandered aimlessly, over rough grass and boggy fields, till he’d flopped down exhausted beneath another tree and slept.

The fog had cleared, the night had passed, the sun had risen, and he, waking under branches, imagined himself still sleeping and dreaming …

The woman placed the teapot on the table and said, ‘So what brings you out so early, Mr W?’

The man glanced at Hat, decided he was out of it for the moment, then said, ‘I’m afraid I’m the bearer of ill news, Miss Mac. I take it you’ve heard nothing?’

‘Heard what? You know I don’t have any truck with phones or wireless.’

‘Yes, I know. But I thought they might have … no, perhaps not … I’m sure that eventually someone will think …’

‘What, for heaven’s sake? Spit it out, man,’ said the woman in exasperation.

‘Perhaps you should sit down … As you will,’ said Waverley as the woman responded with a steely stare that wouldn’t have been out of place on a peregrine. ‘I heard it on the radio this morning, then rang to check details. It’s your nephew, Pal. It’s very bad, I’m afraid. The worst. He’s dead. Like your brother.’

‘Like …? You mean he …?’

‘Yes, I’m truly sorry. He killed himself last night. In Moscow House.’

‘Oh God,’ said the woman. ‘Laurence, you are again my bird of ill omen.’

Now she sat down.

It seemed to Hat, who had emerged from the depths of his introspection just in time to take in the final part of this exchange, that the soft chirruping of the birds, a constant burden since he entered the kitchen, now all at once fell still.

The woman too sat in complete silence for almost a minute.

Finally she said, ‘This is a shock, Laurence. I’m prepared for the shocks of my world, but not for this. Am I needed? Will anyone need me? Please advise me.’

‘I think you should come with me, Lavinia,’ said the man. ‘When you have spoken to people and found out what there is to find out, then you will know if you’re needed.’

The shock of the news had put them on first-name terms, observed Hat. It also underlined his obtrusive presence.

He stood up and said, ‘I think I should be on my way.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ said the woman. ‘Carry on with your breakfast. I think you need it. Laurence, give me five minutes.’

She stood up and went out. The birds resumed their chirruping.

Hat looked at Waverley and said uncertainly, ‘I really think I ought to go.’

‘No need to rush,’ said Waverley. ‘Miss Mac never speaks out of mere politeness. And you do look as if a little nourishment wouldn’t come amiss.’

No argument there, thought Hat.

He sat down and resumed eating his second slice of bread on which he’d spread butter and marmalade to a depth that had the robin tic-ticking in admiration and envy.

Waverley took two mugs from a shelf, and poured the tea.

‘Is there anywhere I can give you a lift to when we go?’ he said.

‘Thank you, I don’t know …’

It occurred to Hat he had no idea where he was in relation to his own vehicle.

To cover his uncertainty, he said, ‘Did you come by car? I didn’t hear it.’

‘I leave it by the roadside. You’ll understand why when you see the state of the track up to the cottage. Miss Mac doesn’t encourage callers.’

Was he being warned off?

Hat said, ‘But she makes them very welcome,’ with just enough stress on she for it to be a counter-blow if the man wanted to take it that way.

Waverley smiled faintly and said, ‘Yes, she has a soft spot for lame ducks, whatever the genus. There you are, my dear.’

Miss Mac had reappeared, having prepared for her outing by pulling a cracked Barbour over her T-shirt and changing her wellies for a pair of stout walking shoes.

‘Shall we be off? Mr Hat, you haven’t finished your tea. No need to rush. Just close the door when you leave.’

Hat caught Waverley’s eye and read nothing there except mild curiosity.

He said, ‘No, I’d better be on my way too. But I’d like to come again some time, if you don’t mind … Sorry, that sounds cheeky, I don’t want to be …’

‘Of course you’ll come again,’ she interrupted as if surprised. ‘Good-looking young man who knows about birds, how should you not be welcome?’

‘Thank you,’ said Hat. ‘Thank you very much.’

He meant it. While he couldn’t say he was feeling well, he was certainly feeling better than he had done for weeks.

They went out of the door he’d come in by. She didn’t bother to lock it. Waste of time anyway with the window left open for the birds.

They went down the side of the cottage, Miss Mac leaning on the stick in her right hand and hanging on to Waverley’s arm with the other as they headed up a rutted track towards a car parked on a narrow country road about fifty yards away.

If Hat had thought of guessing what sort of car Waverley drove, he would probably have opted for something small and reliable, a Peugeot 307 for instance, or maybe a Golf. His enforced absence from work must have dulled his detective powers. Gleaming in the morning sunlight stood a maroon coloured Jaguar S-type.

He said, ‘That lift you offered me, my car’s on the old Stangdale road, if that’s not out of your way.’

‘My pleasure, Mr Hat,’ said Waverley. ‘My pleasure.’

2

the Kafkas at home

Some miles to the south, close to the picturesque little village of Cothersley, dawn gave the mist still shrouding Cothersley Hall the kind of fuzzy golden glow with which unoriginal historical documentary makers signal their next inaccurate reconstruction. For a moment an observer viewing the western elevation of the building might almost believe he was back in the late seventeenth century just long enough after the construction of the handsome manor house for the ivy to have got established. But a short stroll round to the southern front of the house bringing into view the long and mainly glass-sided eastern extension would give him pause. And when further progress allowed him to look through the glass and see a table bearing a glowing computer screen standing alongside an indoor swimming pool, unless possessed of a politician’s capacity to ignore contradictory evidence, he must then admit the sad truth that he was still in the twenty-first century.

A man in a black silk robe sat by the table staring at the screen. He didn’t look up as the door leading into the main house opened and Kay Kafka appeared, clad in a white towelling robe on the back of which was printed IF YOU TAKE ME HOME YOUR ACCOUNT WILL BE CHARGED. She was carrying a tray set with a basket of croissants, a butter dish, two china mugs and an insulated coffee-pot.

Putting the tray on the table she said, ‘Good morning, Tony.’

‘He’s back.’

‘Junius?’ That was the great thing about Kay. You could talk shorthand with her. ‘Same stuff as before?’

‘More or less. Calls himself NewJunius now. Broke in again, left messages and a hyperlink.’

‘I thought they said that was impossible.’

‘They said boil-in-the-bag rice was impossible. His style doesn’t improve.’

‘You seem pretty laid-back about it.’

‘Why not? Some bits I even find myself agreeing with these days.’

‘What bits would they be?’

‘The bits where he suggests there’s more to being a good American than making money.’

‘You tried that one out on Joe lately?’ she asked casually.

‘You know I did, end of last year when the dust had started to settle after 9/11. There were no certainties any more. We talked about everything.’

‘Then after that Joe said it was business as usual, right?’

‘Not so. You’ve got Joe wrong. He feels things as strongly as me. I don’t see him face to face enough, that’s all.’

‘He’s only a flight away,’ she said gently.

It wasn’t a discussion she wanted to get into. Joe Proffitt, head of the Ashur-Proffitt Corporation, wasn’t a man she liked very much, but she didn’t feel able to speak out too strongly against him. Last September she knew that every instinct in Tony Kafka’s body had told him to head for home, permanently. But with Helen three months pregnant, he’d known how his wife would feel about that. So Tony was still here and, as far as she could detect, Joe Proffitt’s business certainties had hardly been dented at all.

‘Yeah, I ought to go more often. It’s as quick going to the States as it is getting to London with these goddam trains,’ he grumbled. ‘Look at me, up with the dawn so I can be sure to be in time for lunch barely a couple of hundred miles away.’

‘You’ll have time for some breakfast?’ she said.

‘No thanks. I’ll get some on the train. What time you get back last night?’

‘Late. Two o’clock maybe, I don’t know. You didn’t wait up.’

‘What for? You may not need sleep but I do, specially with an early start and a long hard day ahead speaking a foreign language.’

‘I thought it was just Warlove you were meeting?’

‘That’s the foreign language I mean.’ They smiled at each other. ‘Anyway, last night when you rang, you didn’t think there was anything there to lose sleep over. Has anything changed? I’ll get asked.’

‘You think they’ll know already?’

‘I’d put money on it,’ he said.

‘It’s cool,’ she said pouring herself some coffee. ‘Domestic drama, that’s all. Main thing is Helen’s fine and the twins don’t seem any the worse for being a tad early.’

‘Good. Born in Moscow House, eh? There’s a turn-up.’

‘Like their mother. Nature likes a pattern. She wants to call the girl Kay.’

‘Yeah, you said. And the boy?’

‘Last night she was talking about Palinurus. Of course she’s very upset over what happened and later she might get to thinking …’

‘A bit ill-omened? Right. And your fat friend is quite happy, is he?’

‘Copycat suicide, no problems.’

‘Copycat suicide? He doesn’t find that a bit weird?’

‘I think in his line of business he takes weird in his stride. I’m having a drink with him later, so I’ll get an update.’

‘Who was it said an update was having sex the first time you went out?’

‘You, I’d guess. No passes from Andy. He is, despite appearances, a kind man.’

‘Yeah,’ he said, as if unconvinced.

Silence fell between them broken by the distant chime of the old long-case clock standing in the main entrance hall. Though it looked as if it had been there almost as long as the house, in fact it had come later than its owners. Kay had spotted it in an antique shop in York. When she’d pointed out the inscription carved on the brass dial – Hartford Connecticut 1846 – Tony had laughed and said, ‘Real American time at last!’ She’d gone back later and bought it for his birthday. He’d been really touched. It turned out to have a rather loud chime which she’d wanted to muffle, but he’d refused, saying, ‘We need to make ourselves heard over here!’ In return, however, he’d conceded when she resisted his proposal to set it five hours behind Greenwich Mean Time.

Now its brassy note rang out eight times.

‘Gotta go,’ said Kafka. ‘Let me know how you get on with Mr Blobby, if you’ve a moment.’

‘Sure. Tony, you’re not worried?’

‘No. Just like to show those bastards I’m on top of things.’

‘You’re sure they’re not getting on top of you?’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘I don’t know … sometimes you get so restless … last night when I got in you were tossing and turning like you were at sea.’

For a moment he seemed about to dismiss her worries, then he shrugged and said, ‘Just the old thing. I dream I hear the fire bells and I know I’ve got to get home but I can’t find the way …’

‘Then you wake up and you’re home and everything’s fine, Right, Tony? This is our home.’

‘Yeah, sure. Only sometimes I think I feel more foreign here than anywhere. Sorry, no. I don’t mean right here with you. That’s great. I mean this fucking country. Maybe all I mean is that America’s where all good Americans ought to be right now. We are good Americans, aren’t we, Kay?’

‘As good as we can be, Tony. That’s all anyone can ask.’

‘I think a time’s coming when they can ask a fucking sight more,’ he said.

Abruptly he stood up, removed his black robe and stood naked before her except for the thin gold chain he always wore round his neck. On it was his father’s World War Two Purple Heart, which he wore as a good-luck charm.

‘Pay me no heed,’ he said. ‘Male menopause. I could pay a shrink five hundred dollars a session to tell me the same. Give my best to Helen.’

He turned away and dived into the swimming pool.

He was in his late forties, but his stocky body, its muscles sculpted into high definition by years of devoted weight training, showed little sign yet of paying its debt to age.

He did a length of crawl, tumble turned, and came back at a powerful butterfly. Back where he started, his final stroke brought his flailing arms down on to the lip of the pool and he hauled himself out in one fluid movement.

When he stops that trick, I’ll know he’s over the hill physically, thought Kay.

But where he was mentally, even her penetrating gaze couldn’t assess.

She watched him walk away, his feet stomping down hard on the tiled floor as if he’d have liked to feel it move. When he vanished through the door, she turned the laptop towards her and began to read.

ASHUR-PROFFITT & THE CLOAK OF INVISIBILITY

A Modern Fairy Tale

Once upon a time some cool dudes in the Greatest Country on Earth decided it would be real neat to sell arms to one bunch of folk they didn’t like at all called the Iranians and give the profits from the sale to another bunch of folk they liked a lot called the Contras. At the same time across the Big Water in the Second Greatest Country on Earth some other cool dudes decided it would be real neat to sell arms to another bunch of folk called the Iraqis that nobody liked much except that they were fighting another bunch of folk called the Iranians that no one liked at all. But it didn’t bother the cool dudes in either of the two Greatest Countries on Earth to know what the other was doing because in each of the countries there were people doing that too and as Mr Alan Clark of the second G.C.O.E. (who was so cool, if he’d been any cooler he’d have frozen over) remarked later, ‘The interests of the West were best served by Iran and Iraq fighting each other, and the longer the better.’

But the really amazing thing about all these dudes on both sides of the Big Water was that they were totally invisible – which meant that, despite the fact that everything they did was directly contrary to their own laws, nobody in charge of the two Greatest Countries on Earth could see what they doing!

She scrolled to the end, which was a long way away. Tony was right about the style. Once this kind of convoluted whimsicality had probably seemed as cool as you could get without taking your clothes off. Now it was just tedious, which was good news from A-P’s point of view. Only the final paragraph held her attention.

There was a time when you could argue a patriotic case – my enemy’s enemy is my friend so treat them all the same then sit back and watch them knock hell out of each other – but no longer. Hawk or dove, republican or democrat, every good American knows there’s a line in the sand and anyone who sends weapons across this line had better be sure which way they’re going to be pointing. The Ashur-Proffitt motive is no longer enough. It’s time we asked these guys just whose side they think they’re on.

She sat back and thought of Tony, of his admission that he felt foreign here. Could it be that now that the twins were born, he thought she might be persuadable to up sticks and head west? Funny that it should come to this, that he whose own father had been born God knows where should be the one who spoke of being a good American and going home, while she whose forebears, from what she knew of them, had been good Americans for at least a couple of centuries, could not bring to mind a single place in the States – save for one tiny plot covering a very few square feet – that exerted any kind of emotional pull. OK, so she agreed, home was a holy thing, but to her this was home, all the more holy since last night. Tony would have to understand that.

The script had vanished to be replaced by a screen saver – the Stars and Stripes rippling in a strong breeze.

She switched it off, leaned back in her chair and closed her eyes. Tony was right. She didn’t need much sleep and she’d perfected the art of dropping off at will for a pre-programmed period. This time she gave herself forty minutes.

When she woke, the sun was up and the mist was rising. She stood up, undid her robe, let it slide to the floor, and dived into the pool. Her slim naked body entered the water with barely a splash and what trace of her entry there was had almost vanished by the time she broke the surface two-thirds of a length away.

She swam six lengths with a long graceful breast stroke. Her exit from the pool was more conventional than her husband’s but in its own way just as athletic.

She slipped into her robe. The legend on the back didn’t amuse her but it amused Tony and his bad jokes were a small price to pay for all he’d done for her. But some stuff she needed to deal with herself. Like last night. Something had happened that she didn’t understand. If she could work it out and defend herself against it, she would. But if it turned out to be part of that darkness against which there was no defence, so what? She’d dealt with darkness before.

In any case, it was trivial alongside the thing that had happened that she did understand. The birth of Helen’s twins. Most dawns were false but you enjoyed the light even if you knew it was illusory.

Whistling ‘Of Foreign Lands and People’ from Schumann’s Childhood Scenes she walked back through the door into the house.

3

a nice vase

By ten o clock that morning, with the curtaining mist raised by a triumphant sun and the brisk breeze that cued the wild daffodils to dance at Blacklow Cottage rattling the slats on his office blinds, Pascoe was far less certain about his uncertainties.

Dalziel had no doubts. His last words had been, ‘Tidy this up, Pete, then dump the lot on Paddy Ireland’s desk. Suicides are Uniformed’s business.’

He was right, of course, except that his idea of tidiness wasn’t the same as Pascoe’s, which was why on his way to work he diverted to the cathedral precinct where Archimagus Antiques was situated.

The closed sign was still displayed in the shop door, but when he peered through the window he saw someone moving within. He banged on the window. A woman appeared, mouthed ‘Closed’ and pointed at the sign. Pascoe in return pressed his warrant against the glass. She nodded instantly and opened the door.

‘I didn’t know what to do,’ she began even before he stepped inside. ‘It was on the news, you see, and I didn’t know if I should come in or not, but David said he thought I should, not to do business, but just in case someone from the police wanted to ask questions, which you clearly do, so he was right, and he’d have come with me but he felt he ought to go round to see poor Sue-Lynn, and I would have gone with him only it seemed better for me to come here.’

She paused to draw breath. She was tall, well made and attractive in a Betjeman tennis girl kind of way. As she spoke she ran her fingers through her short unruly auburn hair. Breathlessness suited her. Early twenties, Pascoe guessed, and with the kind of accent which hadn’t been picked up at the local comp. She was dressed, perhaps fittingly but not too becomingly, in a white silk blouse and a long black skirt. She looked tailor-made for jodhpurs, a silk headsquare and a Barbour.

‘I’m DCI Pascoe,’ he said. ‘And you are …?’

‘Sorry, silly of me, I’m babbling on and half of what I say can’t mean a thing. I’m Dolly Upshott. I work here. Partly shop assistant, I suppose, but I help with the accounts, that sort of thing, and I’m in charge when Pal’s off on a buying expedition. Please, can you tell me anything about what happened?’

‘And this David you mentioned is …?’ said Pascoe, who’d learned from his great master that the easiest way to avoid a question was to ask another.

‘My brother. He’s the vicar at St Cuthbert’s, that’s Cothersley parish church.’

Which was where the Macivers lived, in a house with the unpromising name of Casa Alba. Cothersley was one of Mid-Yorkshire’s more exclusive dormer villages. The Kafkas’ address was Cothersley Hall. Family togetherness? Didn’t seem likely from what he’d gathered about internal relationships last night. Also it was interesting that the brash American incomers should occupy the Hall while Maciver with his local connections and his antique-dealer background should live in a house that sounded like a rental villa on the Costa del Golf.

‘And he’s gone to comfort Mrs Maciver? Very pastoral. Were they active churchgoers then?’

‘No, not really. But they are … were … very supportive of church events, fêtes, shows, that sort of thing, and very generous when it came to appeals.’

What Ellie called the Squire Syndrome. Well-heeled townies going to live in the sticks and acting like eighteenth-century lords of the manor.

‘Miss Upshott,’ said Pascoe, cutting to the chase, ‘the reason I called was to see if you or anyone else working in the shop could throw any light on Mr Maciver’s state of mind yesterday.’

‘There’s only me,’ said the woman. ‘He seemed fine when last I saw him. I left early, middle of the afternoon. It was St Cuthbert’s feast day, you see, and David, my brother, has a special service for the kids from the village school, it’s not really a service, their teacher brings them over and David shows them our stained-glass windows and tells them some stories about St Cuthbert which are illustrated there. He’s very good, actually, the children love it. And I like to help … Sorry, you don’t want to hear this, do you? I’m rattling on. Sorry.’

‘That’s OK,’ said Pascoe with a smile. She was very easy to smile at. Or with. ‘So you don’t know when Mr Maciver left the shop?’