Полная версия

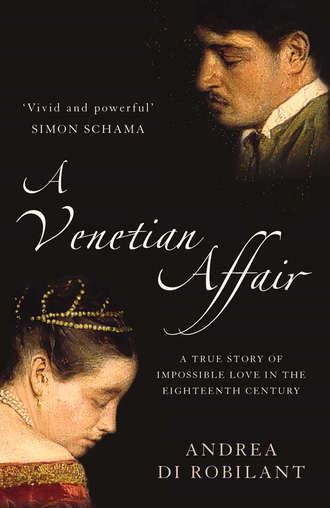

A Venetian Affair: A true story of impossible love in the eighteenth century

“Why should I deny something which at my old age can only go to my credit?”

Andrea had come away from the consul’s rather flustered, not quite knowing whether Smith had spoken to him “truthfully or in jest.” He asked Giustiniana to keep him informed about what she was hearing on her side. “I am greatly curious to know whether there are any new developments.” No one really knew what the consul’s intentions were—whether he was going to propose to Giustiniana or whether he had decided in Betty’s favor. It was not even clear whether he was really interested in marriage or whether he was having fun at everyone’s expense. Giustiniana too found it hard to read Smith’s mind. “He was here until after four,” she reported to her lover. “No news except that he renewed his invitation to visit him at his house in Mogliano and that he took my hand as he left us.”

Andrea feared Smith might be disturbed by the rumors, ably fueled by the Murray clan, that his affair with Giustiniana was secretly continuing, so he remained cautious in his encouragement: perhaps the consul felt he needed more time; his wife, after all, had only recently been buried. Mrs. Anna, however, was determined not to lose the opportunity to further her daughter’s suit, and she eagerly stepped up the pressure.

In the summer months wealthy Venetians moved to their estates in the countryside. As its maritime power had started to decline in the sixteenth century, the Venetian Republic had gradually turned to the mainland, extending its territories and developing agriculture and manufacture to sustain its economy. The nobility had accumulated vast tracts of land and built elegant villas whose grandeur sometimes rivaled that of great English country houses or French châteaux. By the eighteenth century the villa had become an important mark of social status, and the villeggiatura—the leisurely time spent at the villa in the summer—became increasingly fashionable. Those who owned a villa would open it to family and guests for the season, which started in early July and lasted well into September. Those who did not would scramble to rent a property. And those who could not afford to rent frantically sought invitations. A rather stressful bustle always surrounded the comings and goings of the summer season.

Venetians were not drawn to the country by a romantic desire to feel closer to nature. Their rather contrived summer exodus, which Goldoni had ridiculed in a much-applauded comedy earlier that year at the Teatro San Luca,* was a whimsical and ostentatious way of transporting to the countryside the idle lifestyle they indulged in during the winter in the city. In the main, the country provided, quite literally, a change of scenery, as if the burchielli, the comfortable boats that made their way up the Brenta Canal transporting the summer residents to their villas, were also laden with the elaborate sets of the season’s upcoming theatrical production.

Consul Smith had been an adept of the villeggiatura since the early twenties, but it was not until the thirties that he had finally bought a house at Mogliano, north of Venice on the road to Treviso, and had it renovated by his friend Visentini. The house was in typical neo-Palladian style—clear lines and simple, elegant spaces. It faced a small formal garden with classical statues and potted lemon trees arranged symmetrically on the stone parterre. A narrow, well-groomed alley, enclosed by low, decorative gates, ran parallel to the house, immediately beyond the garden, and provided a secure route for the morning or evening walk. The consul had moved part of his collection to adorn the walls at his house in Mogliano, including works by some of his star contemporaries—Marco and Sebastiano Ricci, Francesco Zuccarelli, Giovan Battista Piazzetta, Rosalba Carriera—as well as old masters such as Bellini, Vermeer, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and Rubens. “As pretty a collection of pictures as I have ever seen,”6 the architect Robert Adam commented when he visited Smith in the country.

The consul had often invited the Wynnes to see his beautiful house at Mogliano. Now, in the late spring of 1756, he renewed his invitation with a more urgent purpose: to pay his court to Giustiniana with greater vigor so that he could come to a decision about proposing to her, possibly by the end of the summer. Mrs. Anna, usually rather reluctant to make the visit on account of the logistical complications even a short trip to the mainland entailed for a large family like hers, decided she could not refuse.

The prospect of spending several days in the clutches of the consul did not particularly thrill Giustiniana. She told Andrea she wished the old man “would just leave us in peace” and cursed “that wretched Mogliano a hundred times.” But Andrea explained to her that Smith’s invitation was a good thing because it meant he was serious about marrying her and was hopefully giving up on the spinsterish Betty Murray. Giustiniana continued to dread the visit—and the role that, for once, both Andrea and her mother expected her to play. Her anguish only increased during the daylong trip across the lagoon and up to Mogliano. But once she was out in the country and had settled into Smith’s splendid house, she rather began to enjoy her part and to appreciate the humorous side of her forced seduction of il vecchio—the old man. The time she spent with Smith became good material with which to entertain her real lover:

I’ve never seen Smith so sprightly. He made me walk with him all morning and climbed the stairs, skipping the steps to show his agility and strength. [The children] were playing in the garden at who could throw stones the furthest. And Memmo, would you believe it? Smith turned to me and said, “Do you want to see me throw a stone further than anyone else?” I thought he was kidding, but no: he asked [the children] to hand him two rocks and threw them toward the target. He didn’t even reach it, so he blamed the stones, saying they were too light. He then threw more stones. By that time I was bursting with laughter and kept biting my lip.

The visit to Mogliano left everyone satisfied, and even Giustiniana returned in a good mood. Smith was by now apparently quite smitten and intended to continue his courtship during the course of the summer. As this would have been impossible if the Wynnes stayed in Venice, he suggested to Mrs. Anna that she rent from the Mocenigo family a pleasant villa called Le Scalette in the fashionable village of Dolo on the banks of the Brenta, a couple of hours down the road from Mogliano. Smith himself handled all the financial transactions, and since the rental cost would have been high for Mrs. Anna it is possible that he also covered part of the expenses.

Needless to say, Giustiniana was not happy about the arrangement. It was one thing to spend a few days at Mogliano, quite another to have Smith hovering around her throughout the summer. Meanwhile, where would Andrea be? When would they be able to see each other? She could not stand the idea of being separated from her lover for so long. Andrea again tried to reassure her. There was nothing to worry about: it would probably be simpler to arrange clandestine meetings in the country than it was in town. He would come out as often as possible and stay with trusted friends—the Tiepolos had a villa nearby. He would visit her often. It would be easy.

In the meantime Andrea decided he needed to spend as much time as possible with the consul in order to humor him, allay his suspicions, and steer him ever closer toward a decision about Giustiniana. It soon became apparent that the consul, too, wished to keep his young friend close to him. He said he wanted Andrea at his side to deal with his legal and financial affairs but he was probably putting him to the test, observing him closely to see if he still loved Giustiniana. Never before had he seemed so dependent on him. The two of them became inseparable—an unusual couple traveling back and forth between Venice and Mogliano, where Smith’s staff was preparing the house for the summer season, and making frequent business trips to Padua.

Giustiniana was left to brood over her future alone. She complained about Andrea’s absences from Venice and dreaded the uncertainty of her situation. She did not understand his need to spend so much time with that “damned old man.” She felt they were “wasting precious time” that they could be spending together. Yet her reproaches always gave way to words of great tenderness. During one of Andrea’s overnight trips to the mainland with the consul, she wrote:

You are far away, dear Memmo, and I am not well at all. I am happier when you are here in town even when I know we won’t be speaking because I always bear in mind that if by happy accident I am suddenly free to see you, I can always find a way to tell you. You might run over to see me; I might see you at the window…. And so the time I spend away from you passes less painfully…. But days like this one are very long indeed and seem never to end…. Though I must say there have been some happy moments too, as when I woke up this morning and found two letters from you that I read over and over all day. They gave me so much pleasure…. I still have other letters from you, which I fortunately have not yet returned to you—those too were brought out and given a “tour” today. And your portrait—oh, how sweetly it occupied me! I spoke to it, I told it all the things that I feel when I see you and I am unable to express to you when I am near you…. My mother took me out with her to take some fresh air, and we went for a ride ever so lazily down the canal. And as by chance she was as quiet as I was, I let myself go entirely to my thoughts. Then, emerging from those thoughts, I looked around eagerly, as if I were about to run into you. Every time I saw a boat that seemed to me not unlike yours, I couldn’t stop believing that you might be in it. The same thing happened when we got back home—a sudden movement outside brought me several times to the window where I always sit when I hope to see you…. The evening hours were very uncomfortable. We had several visitors, and I could not leave the company. But in the end they did not bother my heart and thoughts so much because I went to sit in a corner of the room. Now, thank God, I have retired and I am with you with all my heart and spirit. This is always the happiest moment of the evening for me. And you, my soul, what are you doing in the country? Are you always with me? Tonnina now torments me because she wants to sleep and is calling me to bed. Oh, the fussy girl! But I guess I must please her. I will write to you tomorrow. Wouldn’t it be sweet if I could dream I was with you? Farewell, my Memmo, farewell. I adore you…. Memmo, I always, always think of you, always, my soul, yes, always.

As the villeggiatura approached, Giustiniana’s anxiety increased. Andrea still spent most of his time with the consul, working for their future happiness, as he put it. But there was no sign that the consul was any closer to a decision. Furthermore, the idea of spending the summer in the countryside deceiving the old man disconcerted her. She grew pessimistic and began to fear that nothing good would ever come of their cockamamie scheme. Andrea was being unrealistic, she felt, and it was madness to press on: “Believe me, we have nothing to gain and much to lose…. We are bound to commit many imprudent acts. He will surely become aware of them and will be disgusted with both you and me. You will have a very dangerous enemy instead of a friend. As for my mother, she will blame us as never before for having disrupted what she believes to be the best plan she ever conceived.” The two of them carried on regardless, Giustiniana complained—she by ingratiating herself to the consul every time she saw him “as if I were really keen to marry him,” thereby pleasing her mother to no end, and Andrea by “lecturing me all day that I should take him as a husband.” But even if she did, even if the consul, at the end of their machinations, asked her to marry him and she consented, did Andrea really think things would suddenly become easier for them or that the consul would come to accept their relationship? “For heaven’s sake, don’t even contemplate such a crazy idea. Do you believe he would even stand to have you in his house or see you next to me? God only knows the scenes that would take place and how miserable my life would become, and his and yours too.”

In June, as Giustiniana waited for the dreaded departure to the countryside, Andrea’s trips out of town increased. There was more to attend to than the consul’s demands: his own family expected him to pay closer attention to the Memmo estates on the mainland now that his uncle was dead. As soon as he was back in Venice, though, he immediately tried to comfort Giustiniana by reiterating the logic behind their undertaking. He insisted that there was no alternative: the consul was their only chance. He argued for patience and was usually persuasive enough that Giustiniana, by her own admission and despite all her reservations, would melt “into a state of complete contentment” just listening to him speak.

Little by little she was beginning to accept the notion that deception was a necessary tool in the pursuit of her own happiness. But the art of deceit did not come naturally to her. When she was not in Andrea’s arms, enthralled by his reassuring words, her own, more innocent way of thinking quickly took over again, and she would panic: “Oh God, Memmo, you paint a picture of my present and my future that makes me tremble. You say Smith is my only chance. Yet if he doesn’t take me, I lose you, and if he does take me, I can’t see you. And you wish me to be wise…. Memmo, what should I do? I cannot go on like this.”

“Ah, Memmo, I am here now and there is no turning back.”

In early July, after weeks of preparations, the Wynnes had finally traveled across the lagoon and up the Brenta Canal and had arrived at Le Scalette, the villa the consul had arranged for them to rent. The memory of her tearful separation from Andrea in Venice that very morning—the Wynnes and their small retinue piling onto their boat on the Grand Canal while Andrea waved to her from his gondola, apparently unseen by Mrs. Anna—had filled Giustiniana’s mind during the entire boat ride. She had lain on the couch inside the cabin, pretending to sleep so as not to interrupt even for an instant the flow of images that kept her enraptured by sweet thoughts of Andrea. Once they arrived at the villa and had settled in, she cast a glance around her new surroundings and had discovered that the house and the garden were actually very nice and the setting on the Brenta could not have been more pleasant. “Oh, if only you were here, how delightful this place would be. How sweetly we could spend our time,” she wrote to him before going to bed the first night.

The daily rituals of the villeggiatura began every morning with a cup of hot chocolate that sweetened the palate after a long night’s sleep and provided a quick boost of energy. It was usually served in an intimate setting—breakfast in the boudoir. The host and hostess and their guests would exchange greetings and the first few tidbits of gossip before the morning mail was brought in. Plans for the day would be laid out. After the toilette, much of which was taken up by elaborate hairdressing in the case of the ladies, the members of the household would reassemble outdoors for a brief walk around the perimeter of the garden. Upon their return they might gather in the drawing room to play cards until it was time for lunch, a rather elaborate meal that in the grander houses was usually prepared under the supervision of a French cook. Afternoons were taken up by social visits or a more formal promenade along the banks of the Brenta, an exercise the Venetians had dubbed la trottata. Often the final destination of this afternoon stroll was the bottega, the village coffeehouse where summer residents caught up with the latest news from Venice. After dinner, the evening was taken up by conversation and society games. Blindman’s bluff was a favorite. In the larger villas there were also small concerts and recitals and the occasional dancing party.

Giustiniana did not really look forward to any of this. As soon as she arrived at Le Scalette she was seized by worries of a logistical nature, wondering whether it would really be easier for her to meet Andrea secretly in the country than it had been in Venice. She looked around the premises for a suitable place where they could see each other and immediately reported to her lover that there was an empty guest room next to her bedroom. More important: “There is a door not far from the bed that opens onto a secret, narrow staircase that leads to the garden. Thus we are free to go in and out without being seen.” She promised Andrea to explore the surroundings more thoroughly: “I will play the spy and check every corner of the house, and look closely at the garden as well as the caretaker’s quarters—everywhere. And I will give you a detailed report.”

The villa next door belonged to Andrea Tron, a shrewd politician who never became doge but was known to be the most powerful man in Venice (he would play an important role in launching Andrea’s career). Tron took a keen interest in his new neighbors. As an old friend of Consul Smith, he was aware that the death of Smith’s wife had created quite an upheaval among the English residents. Like all well-informed Venetians, he also knew about Andrea and Giustiniana’s past relationship and was curious to know whether it might still be simmering under the surface. He came for lunch and invited the Wynnes over to his villa. Mrs. Anna was pleased; it was good policy to be on friendly terms with such an influential man as Tron. She encouraged Giustiniana to be sociable and ingratiating toward their important neighbor. In the afternoon, Giustiniana took to sitting at the end of the garden, near the little gate that opened onto the main thoroughfare, enjoying the coolness and gazing dreamily at the passersby. Tron would often stroll past and stop for a little conversation with her.

Initially Giustiniana thought his large estate might prove useful for her nightly escapades. She had noticed that there were several casini on his property where she and Andrea could meet under cover of darkness. But thanks to her frequent trips to the servants’ quarters, where she was already forming useful alliances, she had found out that Tron’s casini were “always full of people and even if there should be an empty one, the crowds next door might make it too dangerous” for them to plan a tryst there.

In the end it seemed to her more convenient and prudent to make arrangements with their trusted friends, the Tiepolos: their villa was a little further down the road, but Andrea could certainly stay there and a secret rendezvous might be engineered more safely. Giustiniana even went so far as to express the hope that they might be able to replicate in the countryside “another Ca’ Tiepolo,” which had served them so well back in Venice. She added—her mind was racing ahead—that when Andrea came out to visit it would be best “if we meet in the morning because it is easy for me to get up before everyone else while in the evening the house is always full of people and I am constantly observed.”

As Giustiniana diligently prepared the ground for a summer of lovemaking, she did wonder whether “all this information might ever be of any use to us.” Andrea was still constantly on the move, a fleeting presence along the Brenta. When he was not with the consul at Mogliano, he was traveling to Padua on business, visiting the Memmo estate, or rushing back to Venice, where his sister, Marina, who had not been well for some time, had suddenly been taken very ill. Giustiniana might hear that Andrea was in a neighboring village, on his way to see her. Then she would hear nothing more. Every time she started to dream of him stealing into her bedroom in the dead of night or surprising her at the village bottega, a letter would reach her announcing a delay or a change of plans. So she waited and wrote to him, and waited and wrote:

I took a long walk in the garden, alone for the most part. I had your little portrait with me. How often I looked at it! How many things I said to it! How many prayers and how many protestations I made! Ah, Memmo, if only you knew how excessively I adore you! I defy any woman to love you as I love you. And we know each other so deeply and we cannot enjoy our perfect friendship or take advantage of our common interests. God, what madness! Though in these cruel circumstances it is good to know that you love me in the extreme and that I have no doubts about you: otherwise what miserable hell my life would be.

A few days later she was still on tenterhooks:

I received your letter just as we got up from the table and I flew to a small room, locked myself in, and gave myself away to the pleasure of listening to my Memmo talk to me and profess all his tenderness for me and tell me about all the things that have kept him so busy. Oh, if only you had seen me then, how gratified you would have been. I lay nonchalantly on the couch and held your letter in one hand and your portrait in the other. I read and reread [the letter] avidly, and for a moment I abandoned that pleasure to indulge in the other pleasure of looking at you. I pressed one and the other against my bosom and was overcome by waves of tenderness. Little by little I fell asleep. An hour and a half later I awoke, and now I am with you again and writing to you.

Andrea was finally on his way to see Giustiniana one evening when he was reached by a note from his brother Bernardo, telling him that their sister, Marina, was dying. Distraught, he returned to Venice and wrote to Giustiniana en route to explain his change of plans. She immediately wrote back, sending all her love and sympathy:

Your sister is dying, Memmo? And you have to rush back to Venice? … You do well to go, and I would have advised you to do the same…. But I am hopeful that she will live…. Maybe your mother and your family have written to you so pressingly only to hasten your return…. If your sister recovers, I pray you will come to see me right away…. And if she should pass away, you will need consolation, and after the time that decency requires you will come to seek it from your Giustiniana.

In this manner, days and then weeks went by. Eventually, Giustiniana stopped making plans for secret encounters. There were moments during her lonely wait when she even worried about the intensity of her feelings. What was going on in his mind, in his heart? She had his letters, of course. He was usually very good about writing to her. But his prolonged absence disoriented her. She needed so much to see him—to see him in the flesh and not simply to conjure his image in a world of fantasy. “I tremble, Memmo, at the thought that my excessive love might become a burden on you,” she wrote to him touchingly. “… I have no one else but you … Where are you now, my soul? Why can’t I be with you?”

While she longed for Andrea to appear in the country, Giustiniana also forced herself to be graceful with the consul. He called on the Wynnes regularly, coming by for lunch and sometimes staying overnight at Le Scalette, throwing the household into a tizzy because of his surprise arrivals and the late hours he kept. He took Giustiniana out on walks in the garden and spent time with the family, lavishing his attention on everyone. There was no question in anybody’s mind that the old man was completely taken with Giustiniana and that he was courting her with the intention of marriage. Even the younger children had come to assume that the consul had been “tagged” and already “belonged” to their older sister, as Giustiniana put it in her letters to Andrea.

As she waited for her lover, Giustiniana watched with mild bewilderment the restrained embraces between her sister Tonnina and her young fiancé, Alvise Renier, who was summering in a villa nearby. “Poor fellow!” she wrote to Andrea. “He takes her in his arms, holds her close to him, and still she remains indolent and moves no more than a statue. Even when she does caress him she is so cold that merely looking at her makes one angry. I don’t understand that kind of love, my soul, because you set me on fire if you so much as touch me.” She was being a little hard on her youngest sister. After all, Tonnina was only thirteen and Alvise little older than that; it was a fairly innocent first love. But of course every time Giustiniana saw them together she longed to be in the arms of her impetuous lover.