Полная версия

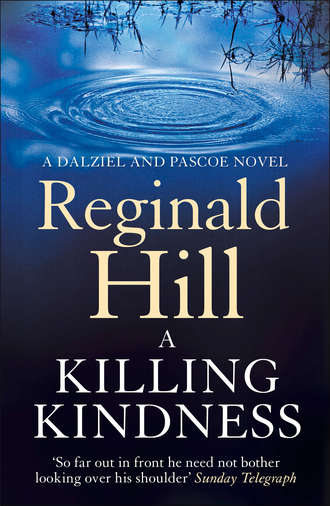

A Killing Kindness

REGINALD HILL

A KILLING KINDNESS

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1980

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Reginald Hill 1980

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN 9780586072516

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN 9780007370252

Version: 2015-06-18

Dedication

For Dan and Pat

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Epigraph

The man that lays his hand upon a woman,

Save in the way of kindness, is a wretch

Whom ’twere gross flattery to name a coward.

JOHN TOBIN: The Honeymoon

Chapter 1

… it was green, all green, all over me, choking, the water, then boiling at first, and roaring, and seething, till all settled down, cooling, clearing, and my sight up drifting with the few last bubbles, till through the glassy water I see the sky clearly, and the sun bright as a lemon, and birds with wings wide as a windmill’s sails slowly drifting round it, and over the bank’s rim small dark faces peering, timid as beasts at their watering, nostrils sniffing danger and shy eyes bright and wary, till a current turns me over, and I drift, and still am drifting, and …

What the hell’s going on here! Stop it! This is sick …

Please. Oh God! Be careful you’ll …

Jack! No!

Ohhhh …

See! Look. The lights … please

… fakery … I don’t want

… lights! Mrs Stanhope, Mrs Stanhope, are you all right?

… auntie, are you OK? Please, auntie …

… thank you, love, I’m a bit … in a minute … did I get …

… vicious blackmailing cow and I’ll see …

‘… picking up lots of forget-me-nots. You make me …’

‘Sorry,’ said Sergeant Wield, switching off the pocket cassette recorder. ‘That was on the tape before.’

‘Pity. I thought she was proving that Sinatra really was dead,’ said Pascoe putting down the sergeant’s handwritten transcription of the first part of the recording. ‘Did you switch off there, or what?’

‘Or what, I think. I had the mike in my pocket, nice and inconspicuous. When I jumped up to grab at Sorby it must’ve fallen out and pulled the connection loose. I’m sorry about all this, sir!’

‘Oh no, you’re not,’ said Pascoe. ‘Not yet. When Mr Dalziel comes through that door with the Evening Post in his hand, that’s when you’re going to be sorry.’

Wield nodded gloomy agreement with the inspector, who now studied his report as if seeking some hidden meaning.

Like all Sergeant Wield’s reports, it was pellucid in its clarity.

Calling on Mrs Winifred Sorby in pursuit of enquiries into the murder of her daughter, Brenda, he had found her in the company of her neighbour, Mrs Annie Duxbury. A short time later, Mrs Rosetta Stanhope and her niece, Pauline, had turned up. Mrs Stanhope was known to the sergeant by reputation as a self-professed clairvoyant and medium. It emerged that Mrs Sorby wished Mrs Stanhope to attempt to get in touch with her dead daughter. The sergeant had been pressed to stay and take part. Agreeing, he had excused himself to go out to his car where he had a small cassette recorder. Concealing this under his jacket, he had returned and joined the women round a table in the dead girl’s darkened bedroom. After a while Mrs Stanhope had seemed to go into a trance and finally started talking in a voice completely different from her own. But only a few moments later the door had burst open and Mr Sorby, the dead girl’s father, had entered angrily and brought the seance to an end.

His fury at his wife’s stupidity had been redirected when he became aware of the sergeant’s presence. He had rapidly found a sympathetic ear for his complaints in the local press and by the time a chastened Wield had returned to the station, Pascoe had already fielded several enquiries about the police decision to use clairvoyance in the Sorby case.

‘His wife’s always gone in for that kind of stuff,’ explained Wield. ‘Sorby’s never approved. Naturally she wasn’t expecting him back for a couple of hours.’

‘Perhaps he’s got second sight,’ grunted Pascoe.

He was examining the transcript again. It had taken Wield nearly an hour of careful listening to sort out the confusion of overlapping voices.

‘Let’s get it straight,’ said Pascoe. ‘Mrs Stanhope in her trance voice. That’s clear. Then Sorby arrives and starts shouting. OK?’

‘Yes,’ said Wield. ‘Next – that’s “Please. Oh God,” etc., is the niece, Pauline. “Jack … no!” – that’s Mrs Sorby.’

‘And this great yell?’

‘Mrs Stanhope coming out of her trance. Then the niece again, Sorby going on about fakery, Mrs Sorby asking Mrs Stanhope if she’s all right.’

‘Which she is. Speaking in her normal voice again, right?’

‘Right. And Sorby again. The niece had jumped up and put the light on. Sorby pushed her aside and looked as if he was going to assault Mrs Stanhope. That’s when I got in on the act.’

‘And the rest is silence,’ said Pascoe. ‘That’s apt.’

‘I wish it had all been bloody silence,’ said Wield. He had one of the ugliest faces Pascoe had ever seen, the kind of ugliness which you didn’t get used to but were taken aback by even if you met him after only half an hour’s separation. The advantage of such an arrangement of features was that it normally blanked out tell-tale signs of emotion. But at the moment unease was printed clearly on the creased and leathery surface.

The phone rang.

It was the desk sergeant.

‘Mr Dalziel’s just come in,’ he said. ‘He’s on his way up.’

The door burst open as Pascoe replaced the receiver.

Detective-Superintendent Andrew Dalziel stood there. A long intermittently observed diet had done something to keep his bulging flesh in check, but now anger seemed to have inflated him till his eyes threatened to pop out of his grizzled bladder of a head and his muscles seemed on the point of ripping apart the dog-tooth twill of his suit.

Like the Incredible Hulk about to emerge, thought Pascoe.

‘Hello, sir. Good meeting?’ he said, half rising. Wield was standing to attention as if rigor mortis had set in.

‘Champion, till I got off the train this end,’ said Dalziel, raising a huge right hand which was attempting to squeeze the printing ink out of a rolled up copy of the local paper.

He pretended to notice Wield for the first time, went close to him and put his mouth next to his ear.

‘Ah, Sergeant Wield,’ he murmured. ‘Any messages for me?’

‘No sir,’ said Wield. ‘Not that I know of.’

‘Not even from the other bloody side!’ bellowed Dalziel. He looked as if he was about to thump the sergeant with the paper.

‘It’s all a mistake, sir,’ interposed Pascoe hastily.

‘Mistake? Certainly it’s a bloody mistake. I go down to Birmingham for a conference. Hello Andy, they all say. How’s that Choker of yours? they all say. Fine, I say. All under control, I say. That was the bloody mistake! You know what it says here in this rag?’

He unfolded the paper with some difficulty.

‘It has long been common practice among American police forces to call on the aid of clairvoyants when they are baffled,’ he read. ‘I leave a normal English CID unit doing its job. I come back and suddenly it’s the Mid-Yorkshire precinct and we’re baffled! No wonder Kojak’s bald.’

Pascoe risked a smile. Lots of things made Dalziel angry. Not having his jokes appreciated was one of them.

The fat man hooked a chair towards him with a size ten foot and sat down heavily.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘Tell me.’

For answer, Pascoe shoved Wield’s report towards him.

He read it quickly.

‘Sergeant.’

‘Sir!’

‘Oh, stop standing there as if you’d crapped yourself,’ said Dalziel wearily.

‘Think I may have, sir,’ said Wield.

This tickled Dalziel’s fancy and he grinned and belched. There had obviously been a buffet bar on the train.

‘How’d it happen you had a recorder in your car, lad? Not normal issue these days, is it?’

‘No, sir,’ said Wield. ‘It’s my nephew’s. It’d gone wonky so I’d been having it repaired.’

‘That was kind of you,’ said Dalziel approvingly. ‘At an electrical shop, you mean?’

‘Not exactly, sir,’ said Wield, uncomfortable again. ‘It’s Percy Lowe who services the radio equipment in the cars. He’s very good with anything like this.’

‘Oh aye. In his own time and with his own gear, I suppose,’ said Dalziel sarcastically.

‘He did a good job on your electric kettle, sir,’ said Pascoe brightly.

Dalziel edged nearer the corner of the desk to scratch his paunch on the angle.

‘Let’s hear what the spirits had to say, then,’ he commanded.

He followed Wield’s transcript closely as the tape was played again.

‘Now that’s what I call helpful,’ he said when it was done. ‘That makes it all worthwhile. Here’s us thinking Brenda Sorby was killed after dark when all the time the sun was shining, and that she was chucked into our muddy old canal that’s so thick Judas bloody Iscariot could walk on it, and all the time it was some nice crystal-clear trout stream!’

‘Sir,’ said Pascoe, but the sarcasm wasn’t yet finished.

‘So all we’ve got to do now, sergeant, is work out the most likely nesting ground for albatrosses in Yorkshire. Or condors, maybe. Wasn’t there a pair seen sitting on a slag heap near Barnsley? That’s it! And these dark-skinned buggers’ll be Arthur Scargill and his lads just up from t’pit!’

Pascoe laughed, not so much at the ‘wit’ as in relief that Dalziel was talking himself back into a good mood. He had known the fat man for many years now and familiarity had bred a complex of emotions and attitudes not least among which was a healthy caution.

‘All right, Peter,’ said Dalziel. ‘This crap apart, what’s really happened today?’

‘Nothing much. House to house goes on, but we’re running out of houses.’

‘And the lad, what about the lad?’

‘Tommy Maggs? I saw him again today while the sergeant was at the Sorbys’. It was just about as useful. He sticks to his story. He’s very uptight, but you’d expect that.’

‘Why?’

‘Well, his girl-friend murdered and the police visiting him twice daily.’

‘Oh aye,’ said Dalziel doubtfully. He glanced at his watch. ‘Well, I’ll tell you what we’ll do,’ he said. ‘How’s your missus?’

Pascoe’s wife, Ellie, was five months gone with their first child.

‘Fine, she’s fine.’

‘Grand,’ said Dalziel. ‘That’s what you need, Peter. A babby around the house. Steady you down a bit.’

He nodded with the tried virtue of a medieval bishop remonstrating with a wild young squire.

‘So if she’s all right, and my watch is all right, the Black Bull’s open and I’ll let you buy me a pint.’

‘A pleasure, sir,’ said Pascoe. ‘But just the one.’

‘Don’t be shy. You can buy me as many as you like,’ said Dalziel.

As he passed Wield, he dug a finger into his ribs and said, ‘You’d best come too, sergeant, in case we move on to spirits.’

He went chuckling through the door.

Pascoe and Wield shared a moment of silent pain and then followed him.

Chapter 2

Brenda Sorby was the third murder victim in less than four weeks.

The first had been Mary Dinwoodie, aged forty, a widow. Disaster had come in the traditional three instalments to Mrs Dinwoodie. Less than a year earlier she and her husband and their seventeen-year-old daughter had been happily and profitably running the Linden Garden Centre in Shafton, a pleasant dormer village a few miles east of town. Then in a macabre accident at the Mid-Yorkshire Agricultural Show, during a parade of old steam traction engines, one of the drivers had suffered a stroke, his machine had turned into the spectators, Dinwoodie had slipped and next thing his crushed and lifeless body was lying on the turf. Five months later, his daughter too was crushed to death in a car accident on an icy Scottish road.

This second tragedy almost destroyed Mrs Dinwoodie. She had left the Garden Centre in the care of her nurseryman and gone off alone. More than three months elapsed before she reappeared. She looked pale and ill but was clearly determined to get back to normality. Ironically it was her first tentative steps in that direction which completed the tragic trilogy.

While the Dinwoodies had made no close personal friends locally, they had not been inactive, their social life being centred on the Shafton Players, the village amateur dramatic group. Mary Dinwoodie had withdrawn completely after her husband’s death, but now, pressed by a kindly neighbour, she had agreed to attend the group’s annual summer ‘night out’. They had had a meal at the Cheshire Cheese, a pub with a small dining-room on the southern outskirts of town. At closing time they had drifted into the car park, calling cheerful goodnights. Mary Dinwoodie had insisted on coming in her own car in case she wanted to get away early. In the event she had stayed to the last and seemed to enjoy herself thoroughly. The other twenty or so revellers had all set off into the night, in groups no smaller than three. And all imagined Mary Dinwoodie was driving home too.

But in the morning her mini was still in the car park.

And a short time afterwards a farm labourer setting out to clear a ditch not fifty yards behind the Cheshire Cheese found her body neatly, almost religiously, laid out amid the dusty nettles.

She had been strangled, or ‘choked’ as the labourer informed any who would listen to him, a progressively diminishing number over the next few days.

But the alliteration appealed to Sammy Locke, news editor of the local Evening Post and ‘The Cheshire Cheese Choking’ was his lead story till public interest faded, a rapid enough process as the labourer could well avow.

Then ten days later the second killing took place. June McCarthy, nineteen, single, a shift worker at the Eden Park Canning Plant on the Avro Industrial Estate, was dropped early one Sunday morning at the end of Pump Road, a long curving street half way down which she lived with her widowed father. Her friends on the works bus never saw her alive again. A septuagenarian gardener called Dennis Ribble opening the shed on his Pump Street allotment at nine-thirty A.M. found her dead on the floor.

She too had been strangled. There were no signs of sexual interference. The body was neatly laid out, legs together, lolling tongue pushed back into the mouth, arms crossed on her breast and, a macabre touch, in her hands a small posy of mint sprigs whose fragrance filled the shed.

There were no obvious suspects. Her father was discovered still in bed and imagining his daughter was in hers. And her fiancé, a soldier from a local regiment, had returned to Northern Ireland the previous day after a week’s leave.

Sammy Locke at the Evening Post read the brief accounts in the national dailies on Monday, looked for an angle and finally composed a headline reading CHOKER AGAIN?

He had just done this when the phone rang. A man’s voice said without preamble, ‘I say, we will have no more marriages.’

Locke was not a literary man, but his secretary, having recently left boring school after one year of a boring ‘A’ level course, thought she recognized a reference to one of the two boring texts she had struggled through (the other had been Middlemarch).

‘That’s Hamlet,’ she announced. ‘I think.’

And she was right.

Act 3, Scene 1. I have heard of your paintings too, well enough; God hath given you one face and you make youselves another; you jig, you amble, and nickname God’s creatures, and make your wantonness your ignorance. Go to, I’ll no more on’t; it hath made me mad. I say we will have no more marriages; those that married already, all but one, shall live; the rest shall keep as they are. To a nunnery, go.

Sammy Locke did not know his Shakespeare but he knew his news and after a little thought he removed the question mark from his headline and rang up Dalziel with whom he had a drinking acquaintance.

Daziel received the information blankly and then consulted Pascoe, whose possession of a second-class honours degree in social science had won him the semi-ironical status of cultural consultant to the fat man. Pascoe shrugged and made an entry in the log book.

And then came Brenda Sorby.

She was just turned eighteen, a pretty girl with long blonde hair who worked as a teller in a suburban branch of the Northern Bank. A picture had emerged of a young woman with the kind of simplistic view of life which is productive of both great naïveté and great resolution. She had told her mother that she would not be home for tea that Thursday evening, and she had been right. After work she was having her hair done, and then she planned to take advantage of the new policy of Thursday night late closing by some of the city centre stores to do some shopping before meeting her boy-friend.

This was Thomas Arthur Maggs, Tommy to his friends, aged twenty, a motor mechanic by trade and an amiable but rather feckless youth by nature. He had got into a bit of trouble as a juvenile, but nothing serious and nothing since. Brenda’s father disapproved of almost everything about Tommy and his circle of friends, but was restrained from being too violent in his opposition by Mrs Sorby, who opined that it was best to let these things run their course. They did, until the night of Brenda’s eighteenth birthday which she celebrated with a party of friends at the town’s most pulsating disco. She returned home happy, slightly merry and wearing a rather flashy engagement ring. Jack Sorby exploded – at Brenda for her stupidity, at Tommy for his duplicity, at his wife for her ill-counsel, at himself for taking heed of it. He subsided only when his threats to throw his daughter out were met by the calm response that in that case she would start living with Tommy that very night.

A truce was agreed, a very ill-defined truce but one which Jack Sorby felt had been treacherously and unilaterally shattered when on that Friday morning only four days later he rose to discover his daughter had not come home the previous night. Once again, all Mrs Sorby’s powers of restraint were called upon to prevent him setting off for the Maggses’ household only a mile away and administering to Tommy the lower-middle-class Yorkshireman’s equivalent of a horsewhipping. Curiously, his genuine if rather over-intense concern for his daughter did not admit any explanation of her absence other than the sexual.

Winifred Sorby had a broader view of her daughter, however. As soon as her husband had left for the local rating office where he was head clerk, she had rung the bank. Brenda was usually there by eight-thirty. She had not yet appeared. At nine, she tried again. Then, putting on a raincoat because, despite the promise of a fine summer day, she was beginning to feel a deep internal chill, she went round to Tommy Maggs’s house.

There was no reply, no sign of life.

The Maggses all worked, a helpful neighbour told her. And, yes, she had seen them all go off at their usual time, Tommy included.

Mrs Sorby went to the police.

The name of Tommy Maggs immediately roused some interest.

At eleven-fifteen the previous night a Panda car crew had been attracted by the sight of an old rainbow-striped mini with its bonnet up and a young man apparently trying to beat the engine into submission with a spanner.

Investigation revealed that it was indeed his own car which had broken down and, despite all his professional ministrations (for it was Tommy Maggs), refused to start. A strong smell of drink prompted the officers to ask how Tommy had spent the evening. With his girl-friend, he told them. She, irritated by the breakdown and being only half a mile or so from her home which was where they’d been heading, had set off on foot.

Had they been in a pub?

No, assured Tommy. No, they definitely hadn’t been in a pub.

But you have been drinking, suggested one of the policemen emerging from the interior of the mini with an almost empty bottle of Scotch in his hand.

A breathalyser test put it beyond all doubt. Tommy was taken to the station for a blood test. His protestations that he had not taken a drink until after the breakdown evoked the kindly meant suggestion that he should save it for the judge. The police doctor was occupied elsewhere looking at a night watchman who’d had his head banged in the course of a break-in and it was well after one A.M. before Tommy was released, a delay which was later to stand him in good stead. By this time it was raining heavily and constabulary kindness was once more evidenced by a lift in a patrol car going in the general direction of his home.

When the police approached him the next day at the Wheatsheaf Garage, his place of work, he assumed it was on the same business and his story came out again – perhaps a little more rounded this time. A quiet romantic drive with his fiancée, the breakdown, Brenda’s departure on foot, his own frustration and the taking of a quick pull on the bottle to soothe his troubled nerves prior to abandoning the useless bloody car and walking home.