Полная версия

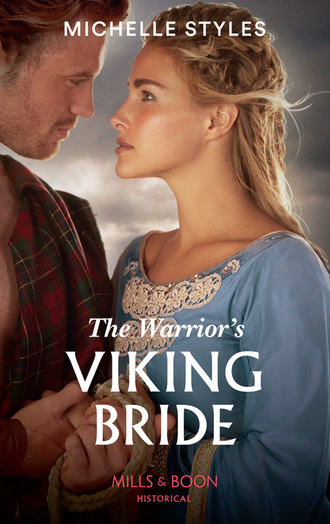

The Warrior's Viking Bride

Her mother hated her talking about it and had once slapped her face when she discovered Dagmar clinging on to the small carved doll Mor had slipped her as they’d parted. The slap had startled her mother and she was instantly sorry, hugging Dagmar and weeping in a dreadful way that she’d never heard before or since. But Dagmar had learned her lesson—she never mentioned her nurse after that and she threw the doll away before her mother spied it again.

‘I’ve no idea,’ she confessed. ‘My Mor was one of the people I left behind when my mother and I departed my father’s lands. I presume she looked after my half-brother. She was a good woman who loved babies. For years, I used to recite her stories in order to get to sleep at night.’

Her throat closed. She could hardly explain how much that woman had meant to her, not to this man. He would only laugh at her. He wouldn’t understand that until the divorce, her mother had been so distracted with the demands of the running the estates and settling disputes, she’d had little time for wiping Dagmar’s tears when she skinned her knee or when her threads tangled or when she woke from bad dreams.

‘No, I’ve no idea what happened to my nurse,’ she reiterated instead. ‘If my mother knew, she kept it to herself.’

‘You’ll soon find out, if you are bothered. Perhaps she will have remained with your father’s family. Perhaps you can do the decent thing and prevail on your father to return her to her kin. She may have a home with my people if her kin have vanished.’

‘I am bothered and it is always best to see what a person desires before making decisions for them,’ she said. ‘You have given me a good reason to look forward to getting to Colbhasa. I thank you for that kindness.’

The Gael grunted.

‘My father must have given you a reason for bringing me back. You must have some idea,’ she said to keep her mind away from the potential reunion with Mor and the fact that she desperately wanted to see her again. She wanted to believe that Mor had been well treated and rewarded for staying with her father. Her mother had forbidden any talk of her previous life when they left the compound on Bjorgvinfjord.

Your life before must be as nothing, keep your face turned to the future.

‘You must ask him when we arrive on Colbhasa. He failed to inform me of the specific reasons, but he is eager to see you and the sort of woman you have become. It was part of the message he sent.’

‘May I hear the precise message?’ She pulled her cloak tighter about her shoulders. ‘I was rude earlier and I apologise. My only excuse was that the battle was about to begin.’

‘It has been overtaken by subsequent events, but here goes.’ The Gael stared out at the marshes, rather than looking at her. ‘Your father requires that you attend him on Colbhasa immediately. He has much to say to you and is eager to see you again after all these years. He wants to see the sort of woman you have become. Do as he requires without delay and all will be well.’

Her mind buzzed. That part of her which had remained a little girl who adored her father wanted desperately for it to be true, that her father had belatedly remembered her and the way they used to be. Just as quickly she remembered the bitter parting—at her stepmother’s urging, he had given them until nightfall to leave his lands or be hunted like wolf’s heads—people who could be slaughtered without having to pay a blood price to their next of kin because they were vermin and not fit to live. Then he’d turned his back on them.

He would want to dictate her future and who she’d marry, but he would soon learn that she was the one who would choose what happened to her. She had earned that right. The Gael would also discover that her fate ran along a different path from the one her father plotted for her, and she looked forward to seeing his face when he realised it irrevocably.

She caught the Gael’s arm. ‘Why does my father want to see the sort of woman I have become? He has another child, a son.’

His eyes blazed and he pulled away from her as if her touch burnt him. ‘His son has died. A snake bite. None could save him. Kolbeinn’s wife claimed it was your mother’s curse. After your half-brother was born, all her other children were either stillborn or died shortly after birth.’

‘Was my brother a robust child?’

‘It doesn’t matter if he was. He is no longer alive.’

Her half-brother, the boy she had never met. The one whose existence had changed hers irrevocably. And now his death was about to change it again, if she allowed it. Her father wanted to secure his legacy. He would certainly have a warrior in mind for her to marry.

She glanced at the Gael and rejected the idea. After what had happened, her father would never risk his chosen bridegroom on retrieving her. This Gael was simply the messenger, the one whose throat she had been supposed to slit. She’d acted like his unwitting executioner.

‘I won’t pretend sorrow.’ Dagmar lifted her chin up. ‘I never knew him. I’m sorry that my father is upset. Tell him that. Tell him that I’ve become a fine and honourable warrior, but I am required elsewhere.’

He inclined his head. ‘You will have the opportunity to tell him that yourself when we reach his hall.’

‘I won’t be seeing him. You may take me back, but it’ll be my stepmother who deals with me. I know who runs that household. Similar sorts of messages have arrived in the past. They were all designed to lure me and my mother into a false sense of security before they attempted to end my life. The messengers all came from my stepmother, rather than my father. Old Alf knew, but how he knew, I couldn’t say.’

Dagmar swallowed hard, remembering how her mother had dispatched one of the messengers and sent the head back—the one who demanded Dagmar make a marriage alliance with a man old enough to be her grandfather, but who had also concealed a knife in his boot.

Her mother had believed that Dagmar should be able to follow her destiny of being a great warrior, rather than being trapped into any sort of marriage.

‘I carried your father’s sword, a parting gift from your father’s current mistress. Old Alf understood its intended meaning.’ A dimple flashed his cheek. ‘He said that he was the only one left who remembered the signal your father had agreed with him.’

‘And how would his mistress know such a thing?’

‘Who knows? She is an older woman.’ The Gael shrugged. ‘I didn’t realise its import myself until I met Old Alf.’

Dagmar clenched her fists. Just when she was starting to feel charitable towards the Gael, he said something so arrogant and short-sighted that it took her breath away. ‘What is it about that particular sword? What is its meaning?’

The tone she used would have her men running for cover, but the Gael dusted an imaginary speck from his cloak as he shook his head as if her antics had no more significance than Mor chasing her tail round and round.

‘Kolbeinn’s wife has died. She lost the will to live when her son died and faded away. I believe the sword signifies that you are no longer in danger.’

Dagmar’s jaw dropped and she staggered back a step, only avoiding falling into a puddle because the Gael’s hand shot out and hauled her back. She shook him off. ‘Dead? My stepmother has perished?’

‘You could see her funeral pyre blazing away across the seas.’

Her stepmother and her son were both dead. The words hammered against her brain. The witch who had featured in her nightmares, the woman who had vowed that she would ensure that Dagmar would not take anything from her children was dead. She no longer had to fear the killers in the night.

‘Forgive me. My head pains me.’ She sank down heavily on a rock and stared at the vast marsh which stretched out in front of her. A faint mist rose off the many pools of water. ‘I can’t pretend anything but joy at the news. She wanted me dead. For the past ten years, I’ve expected an assassin, not a saviour.’

‘Your father wants you alive and with him. Now. I can’t answer for the past.’ He put his hand on her shoulder. To prevent her from running away or to give comfort? Dagmar found that she didn’t care. She drew comfort from it. The last person to touch her like that had been her mother before she’d faced her first battle. ‘Will you come quietly now? Meet him with an open mind?’

‘Does he know about my mother’s death?’ she asked, standing up and moving away from him and the dangerous comfort he offered.

‘He made no mention of it. Kolbeinn kept certain information close to his chest.’

‘Why would he do that?’

‘He has his reasons. Mayhap he wanted rid of a thorn in his side and I was foolish enough to take him up on the offer. I arrogantly considered I could win the wager without too much trouble.’

‘Wagering with my father is unwise.’

Dagmar tapped a finger against her mouth. She could see her father’s reasoning for the wager. He won either way—if she eliminated Aedan mac Connall, he got rid of someone troublesome, but if Aedan returned with her, he gained control of his daughter and his legacy, but it still added up to the end of her dream of independence. He would not understand her desire to stay a shield maiden. He would marry her off to his chosen warrior and increase his own power and prestige. She simply had to figure out a way to get what she desired.

A sudden suspicion made her miss her step. Mor instantly stopped and looked back at her, giving a low woof. The Gael instantly stopped. ‘Why did he choose you, a Gael, and not one of his men? What reason did he give you?’

His eyes grew shadowed. ‘I failed to enquire closely enough it would seem. I was simply grateful of the opportunity.’

‘Why?’ She pressed her hands against her eyes. ‘Surely you have to know the fate of the other messengers. Why risk your life for the promise of gold? You had best tell me all the terms. My father can be trickier than Loki.’

He gave a half-smile. ‘The fate of those other men was hidden from me. We wagered about a debt I owe him. I fulfil the wager and the debt is forgiven. Additionally I get an amount in gold equal to what I owe him if I return with you in the allotted time. He has kept hostages to ensure that I do as he commands. Time marches ever closer to All Hallows.’

Dagmar winced. All Hallows was in a little over a week. She could begin to understand now why this Gael was willing to brave the marshes. ‘What happens if you return with me outside the time?’

‘I lose and become his personal slave and everything I own will belong to him.’

‘How came you to owe him the debt?’

‘It was my brother’s doing. I inherited it when he died.’

‘And you pay your debts.’

‘Being beholden to anyone causes difficulties particularly when they appear with longships, ready to raid.’ His face became grimly set. Dagmar silently cursed her father. Typical of the man. He used others to enforce his will. ‘I will not allow Mhairi or her brothers to remain enslaved.’

‘Who is this Mhairi?’

‘A woman I know.’

‘Your wife?’

‘I’m unmarried, but she volunteered to be a hostage rather than allowing Kolbeinn to make his choice from the women. Her brothers went along to protect her honour. You must admire her courage.’

Dagmar nodded. This Mhairi had sacrificed herself for the Gael with the broad shoulders and the eyes to drown in, even if he refused to admit it. ‘I’d have done that for my mother. This woman has feelings for you.’

He gave a harsh laugh. ‘Mhairi did it for her people, for Kintra, our home, and not for me. She has a deep abiding love for the place and wishes to keep it free from the north. It is what she proclaimed in front of everyone and I’ve no reason to doubt her.’

She nodded again, seeing the sense of it but also knowing there was something that the Gael kept back. Once she had found that out, she’d use it. Right now, without a weapon to defend herself and an army searching for her, she required a protector. One man and his dog. The odds were less than brilliant, but she needed someone on her side and that someone had to be the Gael Aedan mac Connall.

‘My father wants me alive?’ she asked, hardly daring to believe it after so many years. It was only down to her stepmother’s death, but it was more than she had expected. She silently vowed that she would make him see that she would lead the life she had chosen, rather than following whichever path he had chosen.

‘Yes, he does. Very much so. Remember he arranged that sword signal with your friend to keep you safe.’

‘Good to know.’ Dagmar held out her hand. ‘I accept your protection. We travel together once the marshes finish. I will not allow others to be enslaved while I go free.’

He put his fingers about hers—sure and strong. She felt safe as if someone had thrown a warm blanket over her. Dagmar rapidly withdrew her hand.

‘How fares your head?’ he asked. ‘It must hurt like the devil.’

‘It aches as though someone hit me with a very hard object, but I can keep going. I learned a long time ago that the world does not wait for my aches. There are far more important considerations than my discomfort.’

The Gael...no...Aedan mac Connall grunted. It would be easy to start liking him. ‘Good.’

‘We have miles to go before we can sleep,’ she said quickly before she made a fool of herself and confessed how hard trudging through this ghost land was for her. She had to trust this Gael and his dog would find a way out and trust came hard for her as well.

* * *

Aedan glanced back at Dagmar. Her face was pale and intense. Against all expectation, she had trudged through the marsh with barely a murmur. She was far tougher than any other woman he’d ever encountered, and he included Mhairi and his former sister-in-law, Liddy, in that group.

Liddy possessed a different sort of courage, one which he had not fully appreciated until after his brother fell in battle as he single-handedly charged the enemy line and the truth about the boating accident where his niece and nephew were drowned had been revealed. And he’d never thought much of Mhairi until she’d volunteered to be a hostage. But she had done so without shedding a tear or hesitation, declaring that her faith would keep her safe until he had completed his quest. To his eternal regret, he hadn’t appreciated the depth of her feeling for Kintra until that moment.

‘We will stop at the hut. I passed it when I travelled to the east. We still have a long way to go.’

She shaded her eyes and squinted. ‘Are you sure it is there?’

‘I can make out the outlines. We can stop and beg some food.’

‘Steal it, you mean.’

Aedan shook his head in mock despair. ‘Typical Northern response.’

‘You were the one who stole the horse.’

‘That was different.’

She gave a pointed cough. ‘Different how?’

‘There wasn’t time to seek the owner and ask permission,’ Aedan said between gritted teeth. This infuriating woman had a way of twisting things and getting under his skin.

She gave a brilliant smile which transformed her features. His breath caught in his throat. There was something about the hazy light, the damp cloud of golden curls and her smile which did strange things to his insides. His body, which had seemed encased in ice since his former fiancée Brigid’s betrayal, was starting to thaw rapidly. ‘I am very glad you did.’

A strand of her hair touched his fingers. He cleared his throat. ‘The hut. It is where we stop tonight.’

‘I’ll race you.’

‘Mind the oozing mud.’

He caught her arm and prevented her from slipping and falling. A jolt of awareness coursed through him. He released her abruptly.

‘Having come this far, I’ve no wish to lose you to a sink hole.’

She put her hand over where he had held her. Her eyes grew wide. ‘I didn’t see it. I guess I need a protector in more ways than one.’

‘Next time look before you race off.’

Her laugh rang out over the marshes. ‘Now you sound like my old nurse. She used to be always hauling me back from one thing or another.’

‘It has been a long day.’ A long day was reason enough for his unexpected reaction to her. Kolbeinn wanted his daughter back. More than likely to marry her off and secure his legacy. He would want his daughter untouched. Aedan gritted his teeth. There would be more repercussions for his people if he gave in to this attraction for her and he had already caused them enough sorrow. He had to focus on the important things. Mhairi had sacrificed herself without hesitation or expectation. He should be thinking about her and making her his wife, instead of desiring this infuriating witch of a woman. But Mhairi had never sent his blood racing like this shield maiden did.

‘You have done well.’

‘High praise indeed,’ she said drily.

* * *

Dagmar’s stomach gave a loud rumble when they reached the hut, reminding her that it had been some time since she had last eaten. Dead grasses and leaves were blown against the door and the roof exhibited a gaping hole. Closer inspection revealed that the far wall had tumbled down.

‘Shelter for the night,’ Aedan said. ‘Better than sleeping completely out in the open with the rain and midges for company.’

She hated that her dismay must have shown on her face and that he was being kind. Aedan mac Connall was a far easier proposition to hate when he was being officious. ‘It makes it easier that no one is here. No awkward questions. No half-truths to remember.’

‘Sit with Mor by the hut. I will fetch supper.’

‘Oh, you can magic it up out of thin air, can you?’

‘I’m a man of many talents.’ He gave a bow and set off.

Mor flopped down at Dagmar’s feet. When Dagmar made a move to go into the hut, she gave a low growl and shook her head.

‘Shall we be friends? I could use a friend.’ Dagmar held out her hand again. ‘Without you, I’d have been lost.’

The dog gave a cautious sniff before settling her head on her paws.

‘Your master is right,’ Dagmar said, leaning back against the wall and allowing the pale sun which cautiously peeped through the mist to warm her face. She had forgotten what it was like simply to sit. Ever since her mother had died, she had not had a moment to spare. ‘Going through the marshes saves us time. Olafr will suspect that we are making for my father’s, though. The question is—does he realise that I am my father’s sole heir now? Had my mother confided in him about the sword signal? Could it be something he hid from me? Thinking that I’d marry him? He certainly seemed perturbed by your master’s appearance.’

Mor exhaled a loud breath of air which Dagmar took for a ‘yes, you idiotic human’ noise.

She had made the mistake of underestimating Olafr before. She could not afford to make that mistake again. Olafr remained her most potent enemy now that her stepmother was dead.

There was a possibility that Olafr would show up on Colbhasa and spin a convincing tale, something her father would believe and put her in danger, but that was a problem for the future.

Reaching her father was her best hope of long-term survival. Once there, she could make him see that she was equal to any of his warriors, that she could fight for his felag. Marriage to some unknown warrior with more muscles than brains was not inevitable. She could demonstrate to her father that her mother had kept her promise and had ensured her child could compete with the best warriors. Then she could wreak revenge on Olafr. And after that was done, she’d find the peace she’d sought. Some day she would sit with the sun warming her face and nothing more pressing to worry about than harvesting the crops.

‘You needn’t fear, you know. I’ll go to Colbhasa, but I’ll find a way to make the sort of life I want.’

‘Talking to yourself or the dog?’ Aedan reappeared carrying several trout.

Her stomach rumbled. She hated to think how long it had been since she’d had a proper meal.

‘That was fast.’

‘It is easy when you know how to fish. A line and hook is all I require. Simple.’

‘A man of many hidden talents.’

‘An old family secret.’ He turned his back and busied himself with the fire.

‘Have you passed it on to your children?’

‘I don’t have children.’ The tone of his voice had become chipped from ice.

Dagmar frowned. Aedan definitely didn’t like talking about himself. She should leave it, but it was like a sore that she could not stop prodding. ‘Am I keeping you from your bride? Your intended? Is that who Mhairi truly is? It would be like my father to do that as he likes to get his own way.’

‘No. There is no bride. Mhairi lives on Kintra. It surprised me that she even volunteered to be a hostage. I’d not have thought she had it in her, but she obviously did. I’d never considered her as wife material.’

‘Why not?’

Aedan concentrated on building the fire. Why not?

It was a question his people and his priest kept asking. His excuses were wearing thin—first Brigid, his betrothed, the woman he’d loved as a young man, had died, ostensibly while she visited relations. To the world he had grieved, but he and his brother had been the only ones to understand the full extent of her betrayal. Then there was no hurry because his brother had married and had two children. And that marriage had proved little better than his parents’.

Then there was the mess his brother had left behind after he perished in battle which had had to be sorted, but lately the murmurings had grown, particularly his need to provide an heir. Without an heir, Kintra would go to his distant cousin and many doubted if Sean would manage to hold out against the Northmen in the same way as Aedan had, but Aedan wanted something more than a duty-bound marriage doomed to failure.

‘I’ve my reasons,’ he said as he felt Dagmar’s eyes boring into him. ‘Are you married? Before the battle, I had wondered about Olafr and you. He has the sort of looks women usually find irresistible. My brother was the same with women forever buzzing about him.’

‘I’d have sooner married a viper than him.’ Dagmar’s brows lowered and her mouth became a thin white line. She used a pointed stick to draw a line in the dirt. ‘Olafr was my mother’s lover, not mine. Old Alf told me that I should have banished him after he asked for my hand in marriage before the ashes on my mother’s pyre had even gone cold. But I thought he could be useful with his ability to charm Constantine’s court. What a fool I was!’

Deep within him, something rejoiced. Aedan suppressed it. Who she married was none of his business. His business was getting her back to her father so the hostages would be released and his people could prosper. Dagmar was forbidden to him. Aedan inclined his head. ‘I beg your pardon. He simply made it seem as though you two were as one.’

‘Apology accepted. Olafr could charm the birds out of the trees. The ladies certainly twittered about him. He was better at dealing with Constantine and his advisors. I can be too abrupt at times. I dislike fools and see little reason to hide my thoughts.’

‘I hadn’t noticed.’

Her answering laugh rang out, before her face became full of serious intent. ‘My father must accept that I will follow my own chosen path and have no intention of marrying to please him or anyone else.’

‘Indeed.’ Aedan hid his smile. There was little point in explaining that her father would be seeking a son-in-law to rule his lands and command his ships. Dagmar would have little choice but to obey. He would be interested to hear of the clash between father and daughter when it occurred, but please God, make it after he returned to Kintra.

She leant forward. ‘Being a warrior is what my mother trained me for. She believed a woman could and should be a man’s equal. She distrusted marriage and considered that it sapped a woman’s strength.’

‘Did she train you well?’

‘Warfare has been my way of life ever since we left my father’s compound in the north country. I inherited my mother’s felag because she considered me a worthy successor, not because I was her daughter. I’ve an eye for strategy and forward planning. Why should a woman be treated differently than a man?’