полная версия

полная версияWoman. Her Sex and Love Life

William J. Robinson

Woman / Her Sex and Love Life

This old Oriental legend is so exquisitely charming, so superior to the Biblical narrative of the creation of woman, that it deserves to be reproduced in Woman: Her Sex and Love Life. There are several variants of this legend, but I reproduce it as it appeared in the first issue of The Critic and Guide, January, 1903.

At the beginning of time, Twashtri—the Vulcan of Hindu mythology—created the world. But when he wished to create a woman, he found that he had employed all his materials in the creation of man. There did not remain one solid element. Then Twashtri, perplexed, fell into a profound meditation from which he aroused himself and proceeded as follows:

He took the roundness of the moon, the undulations of the serpent, the entwinement of clinging plants, the trembling of the grass, the slenderness of the rose-vine and the velvet of the flower, the lightness of the leaf and the glance of the fawn, the gaiety of the sun's rays and tears of the mist, the inconstancy of the wind and the timidity of the hare, the vanity of the peacock and the softness of the down on the throat of the swallow, the hardness of the diamond, the sweet flavor of honey and the cruelty of the tiger, the warmth of fire, the chill of snow, the chatter of the jay and the cooing of the turtle dove.

He combined all these and formed a woman. Then he made a present of her to man. Eight days later the man came to Twashtri, and said: "My Lord, the creature you gave me poisons my existence. She chatters without rest, she takes all my time, she laments for nothing at all, and is always ill; take her back;" and Twashtri took the woman back.

But eight days later the man came again to the god and said: "My Lord, my life is very solitary since I returned this creature. I remember she danced before me, singing. I recall how she glanced at me from the corner of her eye, how she played with me, clung to me. Give her back to me," and Twashtri returned the woman to him. Three days only passed and Twashtri saw the man coming to him again. "My Lord," said he, "I do not understand exactly how it is, but I am sure that the woman causes me more annoyance than pleasure. I beg you to relieve me of her."

But Twashtri cried: "Go your way and do the best you can." And the man cried: "I cannot live with her!" "Neither can you live without her!" replied Twashtri.

And the man went away sorrowful, murmuring: "Woe is me, I can neither live with nor without her."

PREFACE

In the first chapter of this book I have shown, I believe convincingly, why sex knowledge is even more important for women than it is for men. I have examined carefully the books that have been written for girls and women, and I know that it is not bias, nor carping criticism, but strict honesty that forces me to say that I have not found one satisfactory girl's or woman's sex book. There are some excellent books for girls and women on general hygiene; but on sex hygiene, on the general manifestations of the sex instinct, on sex ethics—none. I have attempted to write such a book. Whether I have succeeded—fully, partially or not at all—is not for me to say, though I have my suspicions. But this I know: in writing this book I have been strictly honest with myself, from first page to last. Whether everything I have written is the truth, I do not know. But at least I believe that it is—or I would not have written it. And I can solemnly say that the book is free from any cant, hypocrisy, falsehood, exaggeration or compromise, nor has any attempt been made in any chapter to conciliate the stupid, the ignorant, the pervert, or the sexless.

As in all my other books I have used plain, honest English. Not any plainer than necessary, but plain enough to avoid obscurity and misconception.

Science and art are both necessary to human happiness. This is not the place to discuss the relative importance of the two. And, while I have no patience with art-for-art's-sake, I recognize that the scientist can not be put into a narrow channel and ordered to go into a certain definite direction. Scientific investigations which seemed aimless and useless have sometimes led to highly important results, and I would not disparage science for its own sake. It has its uses. Nevertheless I personally have no use for it. To me everything must have a direct human purpose, a definite human application. When the cup of human life is so overflowing with woe and pain and misery, it seems to me a narrow dilettanteism or downright charlatanism to devote one's self to petty or bizarre problems which can have no relation to human happiness, and to prate of self-satisfaction and self-expression. One can have all the self-expression one wants while doing useful work.

And working for humanity does not exclude a healthy hedonism; not the narrow Cyrenaic, but an enlightened altruistic hedonism. And in writing this book I have kept the human problem constantly before my eyes. It was not my ambition merely to impart interesting facts: my concern was the practical application of these facts, their relation to human happiness.

If this book should be instrumental, as I confidently trust it will, in destroying some medieval superstitions, in dissipating some hampering and cramping errors, in instilling some hope in the hearts of the hopeless, in bringing a little joy into the homes of the joyless, in increasing in however slight a degree the sum total of human happiness, its mission shall have been gloriously fulfilled.

For this is the mission of the book: to increase the sum total of human happiness.

W.J.R.12 Mount Morris Park W.,

New York City.

Jan. 1, 1917.

CONTENTS

WOMAN: HER SEX AND LOVE LIFE

WOMAN: HER SEX AND LOVE LIFE

Chapter One

THE PARAMOUNT NEED OF SEX KNOWLEDGE FOR GIRLS AND WOMEN

Why Sex Knowledge is of Paramount Importance to Girls and Women—Reasons Why a Misstep in a Girl Has More Serious Consequences than a Misstep in a Boy—The Place Love Occupies in Woman's Life—Woman's Physical Disabilities.

All are agreed—I mean all who are capable of thinking and have given the subject some thought—that for the welfare of the race and for his own physical and mental welfare it is important that the boy be given some sex instruction. All are not agreed as to the character of the instruction, its extent, the age at which it should be begun and as to who the teacher should be—the father, the family physician, the school teacher or a specially prepared book—but as to the necessity of sex knowledge for the boy there is now substantial agreement—among the conservatives as well as among the radicals.

No such agreement exists concerning sex knowledge for the girl. Many still are the men and women—and not among the conservatives only—who are strongly opposed to girls receiving any instruction in sex matters. Some say that such instruction—except a few hygienic rules about menstruation—is unnecessary, because the sex instinct awakens in girls comparatively late, and it is time enough for them to learn about such matters after they are married. Others fear that sex knowledge would destroy the mystery and romance of sex, and would rob our maidens of their greatest charms—modesty and innocence. Still others fear that sex instruction would tend to awaken the sex instinct in our girls prematurely; would direct their thoughts to matters about which they would not think otherwise; and they argue that the warnings about venereal disease, prostitution, etc., which are an integral part of sex instruction, tend to create a cynical, inimical attitude towards the male sex, which may even result in hypochondriac ideas and antagonism to marriage.

I do not deny that there is a grain of truth in all the above objections. Sex instruction does cause some girls to think of sex matters earlier than they otherwise would, and some girls have been made bitter and hypochondriac, and disgusted with the male sex. But it would not be difficult to demonstrate that it was not sex instruction per se that was responsible for these deplorable results; it was the wrong kind of instruction that was to blame—it was the wrong emphasis, the lurid exaggerations that caused the mischief, and not the truth. In other words, it is not sex information, it is sex misinformation, that is pernicious. And, of course, to this everybody will agree: rather than false information, better no information at all.

But if the information to be imparted be sane, honest and truthful, without exaggerating the evils and without laying undue emphasis on the dark shadows of our sex life, then the results can be only beneficent. And the task I have put before myself in this book is to give our girls and women sane, square and honest information about their sex organs and sex nature, information absolutely free from luridness, on the one hand, and maudlin sentimentality, on the other. The female sex is in need of such information, much more so than is the male sex. Yes, if boys, as is now universally agreed, are in need of sex instruction, then girls are much more in need of it. Why? For several important reasons.

The first reason why sex instruction is even more important for girls than it is for boys is because a misstep in a girl has much more disastrous consequences than it has in a boy. The disastrous results of a misstep in a boy are only physical in character; the results of the same misstep in a girl may be physical, moral, social and economic. To speak more plainly. If a boy, through ignorance, rashly indulges in illicit sexual relations, the worst consequence to him may be infection with a venereal disease. But he is not considered immoral, he is not despised, he is not ostracized, he does not lose his social standing in the slightest degree, and when he is cured of his venereal disease he has no difficulty in getting married. He does not even have to conceal his past sexual history from his wife. But if a girl makes a misstep the consequences to her are terrible indeed; it may not only cost her her health and social standing, she may have to pay with her very life. She runs the risk of venereal infection the same as the boy does, but in addition she runs the risk of becoming pregnant, which in our present social system is a catastrophe indeed. To save herself from the disgrace of an illegitimate child she may have an abortion produced; the abortion may have no bad results, but it may, if performed bunglingly, leave her an invalid for life, or it may kill her outright. If she is so unfortunate as to be unable to get anybody to produce an abortion, she gives birth to an illegitimate child, which she is forced in most cases to put away in an institution of some sort where she hopes and prays it may die soon—and, in general, it does. If it does not die, she has for the rest of her life a Damocles' sword hanging over her head, and she is in constant terror lest her sin be found out. She does not permit herself to look for a mate, but if she does get married, the specter of her antematrimonial experience is constantly before her eyes. After years and years of married life, the husband may divorce her if he finds out that she had "sinned" before she knew him. And unless the husband is a broad-minded man and loves her truly and unless she made a clean breast of everything to him before marriage, her life is continuous torture. But even if the girl escaped pregnancy, the mere finding out that she had an illicit experience deprives her of social standing, or makes her a social outcast and entirely destroys or greatly minimizes her chances of ever marrying and establishing a home of her own. She must remain a lonely wanderer to the end of her days.

The enormous difference in the results of a misstep in a boy and a girl is clearly seen, and for this reason alone, if for no other, sex instruction is of more importance to the girl than it is to the boy.

But there are other important reasons, and one of them is beautifully and truthfully expressed by Byron in his two well-known lines.

Man's love is of man's life a thing apart,'Tis woman's whole existence.Yes, love is a woman's whole life.

Some modern women might object to this. They might say that this was true of the woman of the past, who was excluded from all other avenues of human activity. The woman of the present day has other interests besides those of Love. But I claim that this is true of only a small percentage of women; and in even this small minority of women, social, scientific and artistic activities cannot take the place of love; no matter how busy and successful these women may be, they will tell you if you enjoy their confidence that they are unhappy, if their love life is unsatisfactory. Nothing, nothing can fill the void made by the lack of love. The various activities may help to cover up the void, to protect it from strange eyes, they cannot fill it. For essentially woman is made for love. Not exclusively, but essentially, and a woman who has had no love in her life has been a failure. The few exceptions that may be mentioned only emphasize the rule.

But not only psychically is a woman's love and sex life more important than a man's, physically she is also much more cognizant of her sex and much more hampered by the manifestation of her sex nature than man is. To take but one function, menstruation. From the age 13 or 14 to the age of forty-five or fifty it is a monthly reminder to woman that she is a woman, that she is a creature of sex; and, while to many women this periodically recurring function is only a source of some annoyance or discomfort, to a great number it is a cause of pain, headache, suffering, or complete disability. Man has no such phenomenon to annoy him practically his whole life.

But more important are the results of love-union, of sex relations. A man after a sexual relation is just as free as he was before. A woman, if the relation has resulted in a pregnancy, which is generally the case, unless special pains are taken it should not so result, has nine troublesome months before her, months of discomfort if not of actual suffering; she then has an extremely trying and painful ordeal, that of childbirth, and then there is another trying period, the period of lactation or of nursing and of bringing up the baby. The penalty seems almost too great.

And when the woman is on the point of ceasing to menstruate she does not do so smoothly and comfortably. She has to go through a period called the menopause, which may last one or two years and which may bring discomforts and dangers of its own. Man does not have to go through such a distinct period of demarcation separating his sexual from his non-sexual life. Altogether it cannot be denied that woman is much more a slave of her sex nature than man is of his. Yes, Nature has handicapped woman much more heavily than she has man.

In short, both in view of the fact that sexual ignorance with its possible missteps has much more disastrous consequences for the girl than it has for the boy, and in view of the fact that the sex instinct and its physical and psychic manifestations occupy a much more important part in woman's life than they do in the life of man, we consider the necessity of sex instruction much greater in the case of woman than in the case of man. I do not wish to be misunderstood as underestimating the need of sex instruction for the male—only I consider the need even greater in the case of the female.

Chapter Two

THE FEMALE SEX ORGANS: THEIR ANATOMY

The Internal Sex Organs—The Ovaries—The Fallopian Tubes—The Uterus—The Divisions of the Uterus—Anteversion, Anteflexion, Retroversion, Retroflexion, of the Uterus—Endometritis—The Vagina—The Hymen—Imperforate Hymen—The External Genitals—The Vulva, Labia Majora, Labia Minora, the Mons Veneris, the Clitoris, the Urethra—The Breasts—The Pelvis—The Difference Between the Male and Female Pelvis.

The organs which primarily distinguish one sex from the other are the sex organs. It is by the aid of the sex organs that children are begotten and brought into the world, that the race is reproduced and perpetuated. It is for this reason that the sex organs are also called the Reproductive Organs.

The first thing we must do is to become familiar with the structure and location of the sex organs; in other words, we must get a fair idea of their Anatomy.

The female sex organs, also called the reproductive or generative organs, are divided into internal and external. The internal are the most important and consist of: the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, uterus or womb, and vagina. The external sex organs of the female are: the vulva, hymen, and clitoris. Among the external organs are also generally included the mons Veneris and the breasts or mammary glands.

SUBCHAPTER A

THE INTERNAL SEX ORGANS

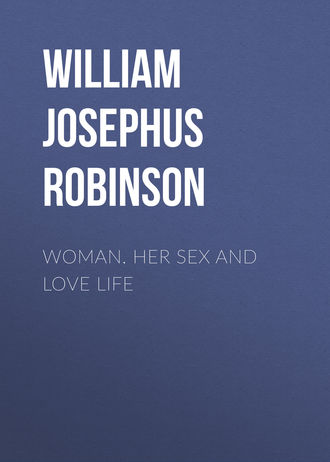

The Ovaries. The ovaries are the essential organs of reproduction. For it is they that generate the eggs, or ova, or ovules, which, after becoming fertilized or fecundated by the spermatozoa of the male, develop into children. Without the ovaries of the female, the same as without the testicles of the male (to which they correspond), no children could be begotten, and the entire human race would quickly disappear from our planet. The ovaries are two in number; they are embedded in the broad ligaments which support the womb in the pelvis, one on each side of the womb. They are of a grayish or whitish pink color, and are about an inch and a half long, three-quarters of an inch wide, and one-third of an inch thick. They weigh from one-eighth to one-quarter of an ounce. Their surface is either smooth or rough and puckered. Think of a large blanched almond and you will have a pretty fair idea of the size and shape of an ovary.

Ovary.

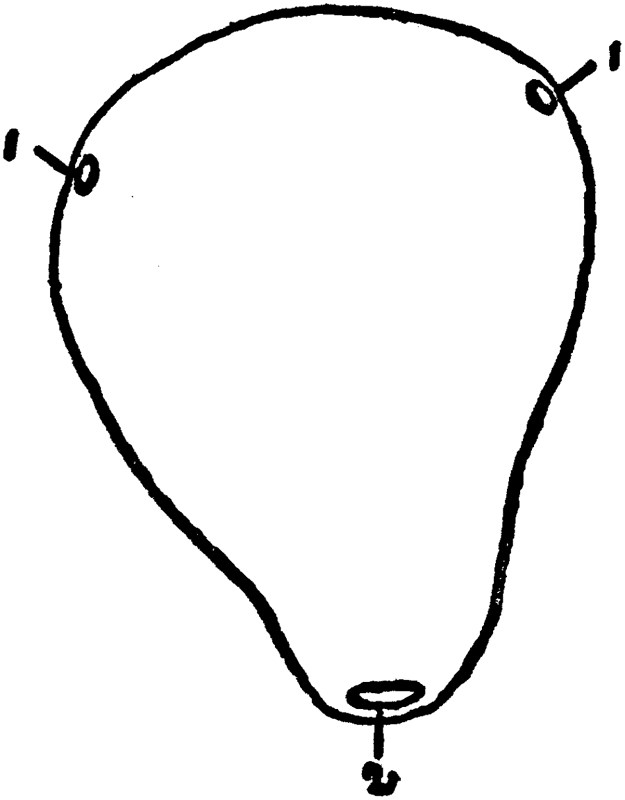

The Fallopian Tubes. The Fallopian tubes (so called from Fallopius, a great anatomist, who discovered them; also called oviducts: egg conductors, because they conduct the eggs from the ovary into the uterus) are two very thin tubes, extending one from each upper angle of the womb to the ovaries; but at their ovarian end they expand into a fringed and trumpet-shaped extremity. The fringes are referred to as fimbria. They are about five inches long and only about one-sixteenth of an inch in diameter; the function of the tubes is to catch the ova as they burst forth from the ovaries and to convey them to the uterus. Taking into consideration the very narrow lumen, or caliber, of the Fallopian tubes, it is easy to understand why even a very slight inflammation is apt to clog them up, to seal their mouths or openings, thus rendering the woman sterile, or incapable of having children. For, if the Fallopian tubes are "clogged" up, the eggs, or ova, have no way of reaching the uterus.

The Greek name for the Fallopian tube is salpinx (salpinx in Greek means tube). An inflammation of the Fallopian tube is therefore called salpingitis. (A salpingitis has the same effect in causing sterility in the female as has an epididymitis in the male.) Salpingectomy is the cutting away of the whole or of a piece of the Fallopian tube (corresponds to vasectomy in the male).

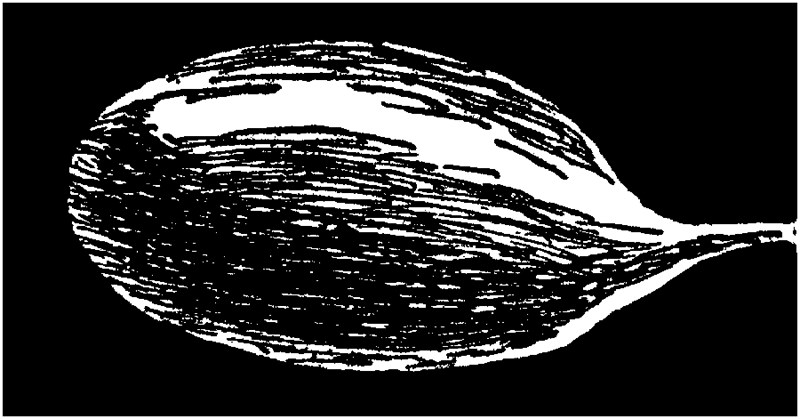

1. Openings into the Fallopian Tubes. 2. Mouth of the Womb.

The Uterus. The uterus or womb is the organ in which the fertilized ovum, or egg, grows and develops into a child. It is a hollow muscular organ, about the size of a pear, with thick walls, capable under the influence of pregnancy of great expansion and growth. The broad part of the pear is called the body of the uterus; the lower narrow part is called the neck of the uterus, or cervix. The uterus in the adult girl or woman is about three inches long, two inches broad in its upper part and nearly an inch thick. It weighs from an ounce to an ounce and a half. When the uterus is in a pregnant condition, it increases enormously, both in size and in weight, as we will see in a future chapter. The cavity of the uterus is somewhat triangular in shape; at each upper angle is the small opening communicating with the Fallopian tube; the upper portion of the uterus is called the fundus; the external opening of the womb, situated in the center of the cervix, is called the mouth of the womb, or the os, or external os.

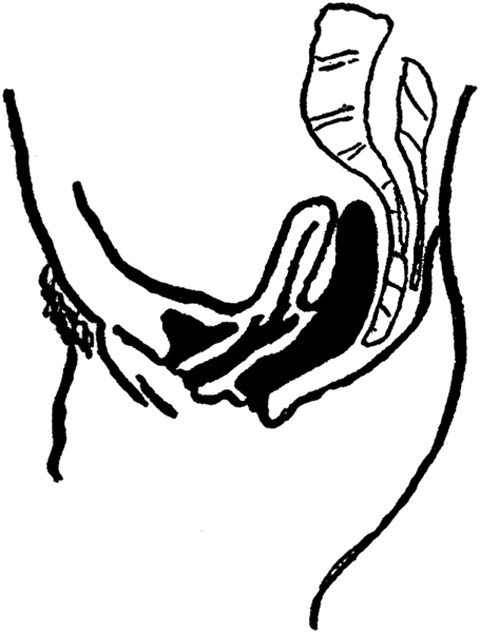

The uterus is situated in the center of the pelvis, between the bladder and the rectum. It is supported by certain ligaments, the chief of which are the broad ligaments; but, on account of general weakness, too hard physical labor, or lifting heavy weights, the ligaments may stretch, and the uterus may sink down low in the vagina, and we then have the condition known as prolapse of the womb. Or, the womb may turn forward, when we have a condition of anteversion. If the womb is bent (or flexed) forward on itself the condition is called anteflexion. If the womb is turned backwards, the condition is called retroversion; if it is bent or flexed backward upon itself the condition is called retroflexion. An extreme degree of anteversion or anteflexion, or retroversion or retroflexion, may interfere with impregnation, as the spermatozoa may find it difficult or impossible to reach the opening of the womb—the external os.

The entire cavity of the uterus is lined by a mucous membrane;1 this mucous membrane is called the endometrium (endo—within; metra—uterus). An inflammation of the endometrium is called endometritis. It is the endometrium that is principally concerned in menstruation—that is, it is from it that the monthly discharge of blood comes.

The Vagina [vagina in Latin—a sheath]. The vagina is the tube or canal which serves as a passage-way between the uterus and the outside of the body. It extends from the external genitals or vulva to the neck of the womb, embracing the latter for some distance. It is a strong, fibromuscular canal, lined with mucous membrane. It is not smooth inside, but arranged in folds, or rugæ, so that when necessary, as during childbirth, it can stretch enormously and permit the passage of a child's head. The length of the vaginal canal is between three and five inches, but it is in general much more capacious in women that have borne one or more children than in those who have not borne any.

Near the vaginal entrance are situated two small glands; they are about the size of a pea, and secrete mucus. They are called Bartholin's glands; occasionally they become inflamed and give a good deal of trouble.

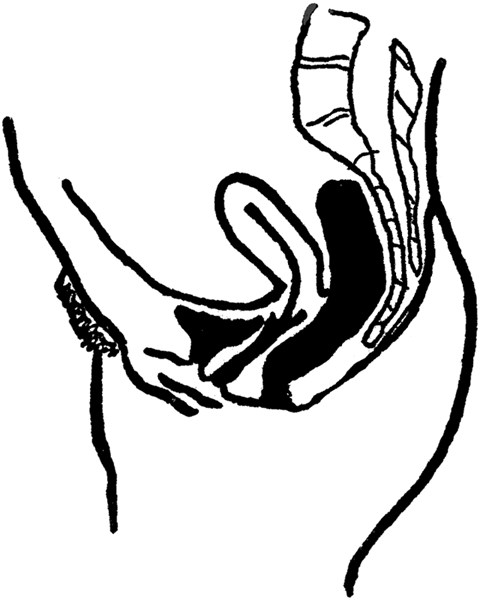

Anteversion of the Uterus.

Anteflexion of the Uterus.

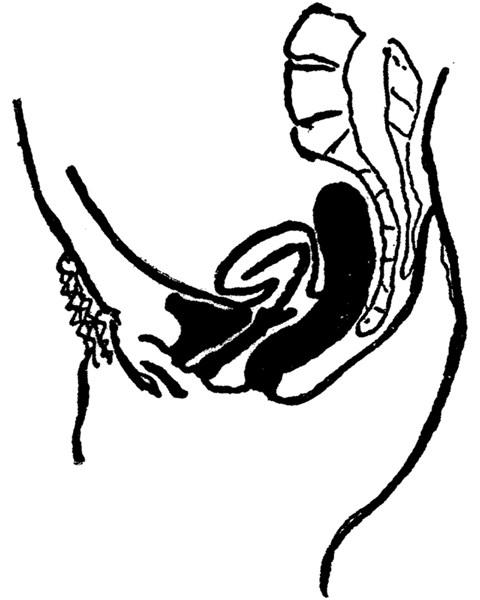

Retroversion of the Uterus.

Retroflexion of the Uterus.

The Hymen [hymen in Greek—a membrane]. The external opening of the vagina, in virgins, that is, in girls or women who have not had sexual intercourse, is almost entirely closed by a membrane called the hymen. The vulgar name for hymen is "maidenhead." The hymen may be of various shapes, and of different consistency. In some girls it is a very thin membrane, which tears very readily; in others it is quite tough. On the upper margin or in the center of the hymen there is an opening which permits any secretion from the vagina and the blood from the uterus to come through. In rare cases there is no opening in the hymen, that is, the vagina is entirely closed. Such a hymen is called imperforate (not perforated). When the girl begins to menstruate, the blood cannot come out and it accumulates in the vagina. In such cases the hymen must be opened or slit by a doctor. In some cases the hymen is congenitally absent; that is, the girl is born without any hymen. While the hymen is usually ruptured during the first intercourse, it, in some cases, being elastic and stretchable, persists untorn after sexual intercourse. It will therefore be seen that just as the presence of the hymen is no absolute proof of virginity, so is the absence of the hymen no absolute proof that the girl has had sexual relations, She might have been born without any hymen, or it might have been ruptured by vaginal examination, by a vaginal douche, by scratching to relieve itching, or by some accident.