полная версия

полная версияThrough Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

"That is the right spirit," the other said approvingly. "It is the same with all of us. There is no difficulty in getting recruits, when there is fighting to be done. It is the dull life in camp that prevents men from joining. We have enlisted twice as many men, in the past three months, as in three years before."

So they talked till night fell and then turned in; putting Lisle between them, that being the warmest position.

In the morning the march was resumed in the same order, Lisle again taking his place with the baggage guard. The march this time was only a single one; but it was long, nevertheless. Lisle was able to keep his place till the end, feeling great benefit from the ghee which he had rubbed on his feet. The havildar, at starting, said a few cheering words to him; and told him that, when he felt tired, he could put his rifle and pouch in the waggon, as there was no possibility of their being wanted.

His two comrades, when they heard that he had accomplished the march without falling out, praised him highly.

"You have showed good courage in holding on," one of them said. "The march was nothing to us seasoned men, but it must have been trying to you, especially as your feet cannot have recovered from yesterday. I see that you will make a good soldier, and one who will not shirk his work. Another week, and you will march as well as the best of us."

"I hope so," Lisle said. "I have always been considered a good walker. As soon as I get accustomed to the weight of the rifle and pouch, I have no doubt that I shall get on well enough."

"I am sure you will," the other said cordially, "and I think we are as good marchers as any in India. We certainly have that reputation and, no doubt, it was for that reason we were chosen for the expedition, although there are several other regiments nearer to the spot.

"From what I hear, Colonel Kelly will be the commanding officer of the column, and we could not wish for a better. I hear that there is another column, and a much stronger one, going from Peshawar. That will put us all on our mettle, and I will warrant that we shall be the first to arrive there; not only because we are good marchers, but because the larger the column, the more trouble it has with its baggage.

"Baggage is the curse of these expeditions. What has to be considered is not how far the troops can go, but how far the baggage animals can keep up with them. Some of the animals are no doubt good, but many of them are altogether unfitted for the work. When these break down they block a whole line; and often, even if the march is a short one, it is very late at night before the last of the baggage comes in; which means that we get neither kit, blankets, nor food, and think ourselves lucky if we get them the next morning.

"The government is, we all think, much to blame in these matters. Instead of procuring strong animals, and paying a fair price for them; they buy animals that are not fit to do one good day's march. Of course, in the end this stinginess costs them more in money, and lives, than if they had provided suitable animals at the outset."

Lisle had had a great deal of practice with the rifle, and had carried away several prizes shot for by the officers; but he was unaccustomed to carry one for so many hours, and he felt grateful, indeed, when a halt was sounded. Fires were lighted, and food cooked; and then all lay down, or sat in groups in the shade of a grove. The sense of the strangeness of his condition had begun to wear off, and he laughed and talked with the others, without restraint.

Up to the time when he joined the regiment, Lisle had heard a good deal of the state of affairs at Chitral; and his impression of the natives was that they were as savage and treacherous a race as was to be found in Afghanistan and Kashmir. Beyond that, he had not interested himself in the matter; but now, from the talk of his companions, he gained a pretty clear idea of the situation.

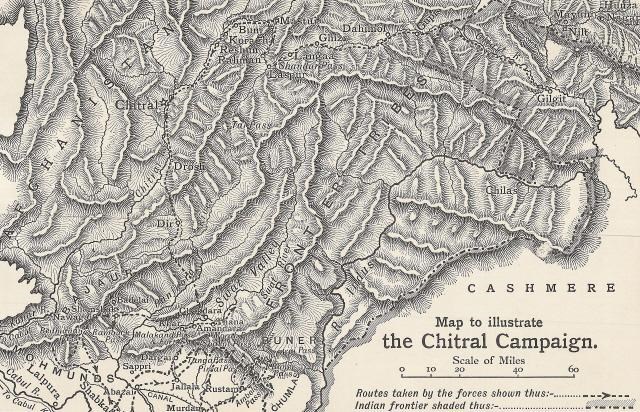

Old Aman-ul-mulk had died in August, 1892. He had reigned long; and had, by various conquests and judicious marriages, raised Chitral to a position of importance. The Chitralis are an Aryan race, and not Pathans; and have a deep-rooted hatred of the Afghans.

In 1878 Aman placed Chitral under the nominal suzerainty of the Maharajah of Kashmir and, Kashmir being one of the tributary states of the Indian Empire, this brought them into direct communication with the government of India; and Aman received with great cordiality two missions sent to him. When he died, his eldest son Nizam was away from Chitral; and the government was seized by his second son, Afzul; who, however, was murdered by his uncle, Sher Afzul. Nizam at once hurried to Chitral; and Sher Afzul fled to Cabul, Nizam becoming the head of the state or, as it was called, Mehtar. Being weak, he asked for a political officer to reside in his territory; and Captain Younghusband, with an escort of Sikhs, was accordingly sent to Mastuj, a fort in Upper Chitral.

However, in November Nizam was also murdered, by a younger brother, Amir. Amir hurried to Chitral, and demanded recognition from Lieutenant Gurdon; who was, at the time, acting as assistant British agent. He replied that he had no power to grant recognition, until he was instructed by the government in India. Amir thereupon stopped his letters, and for a long time he was in imminent danger, as he had only an escort of eight Sikhs.

On the 8th of January, fifty men of the 14th Sikhs marched down from Mastuj and, on the 1st of February, Mr. Robertson, the British agent, arrived from Gilgit. He had with him an escort of two hundred and eighty men of the 4th Kashmir Rifles, and thirty-three Sikhs; and was accompanied by three European officers. When he arrived he heard that Umra Khan had, at the invitation of Amir, marched into Chitral; but that his progress had been barred by the strong fort of Drosh. As the Chitralis hate the Pathans, they were not inclined to yield to the orders of Amir to surrender the fort, and were consequently attacked. The place, however, was surrendered by the treachery of the governor. Amir then advanced, and was joined by Sher Afzul.

Mr. Robertson wrote to Amir Khan, saying that he must leave the Chitral territory. Amir paid no attention to the order, and Mr. Robertson reported this to the government of India. They issued, in March, 1895, a proclamation warning the Chitralis to abstain from giving assistance to Amir Khan, and intimating that a force sufficient to overcome all resistance was being assembled; but that as soon as it had attained its object, it would be withdrawn.

The Chitralis, who now preferred Sher Afzul to Amir, made common cause with the former. Mr. Robertson learned that men were already at work, breaking up the road between Chitral and Mastuj; and accordingly moved from the house he had occupied to the fort, which was large enough to receive the force with him.

On the 1st of March, all communications between Mr. Robertson and Mastuj had ceased; and troops were at once ordered to assemble, to march to his relief. It was clearly impossible for our agent to retire as, in order to do so, he would have to negotiate several terrible passes, where a mere handful of men could destroy a regiment. Thus it was that the Pioneers had been ordered to break up their cantonment, and advance with all speed to Gilgit.

Hostilities had already begun. A native officer had started, with forty men and sixty boxes of ammunition, for Chitral; and had reached Buni, when he received information that his advance was likely to be opposed. He accordingly halted and wrote to Lieutenant Moberley, special duty officer with the Kashmir troops in Mastuj. The local men reported to Moberley that no hostile attack upon the troops was at all likely but, as there was a spirit of unrest in the air, he wrote to Captain Ross, who was with Lieutenant Jones, and requested him to make a double march into Mastuj. This Captain Ross did and, on the evening of the 4th of March, started to reinforce the little body of men that was blocked at Buni.

On the same day a party of sappers and miners, under Lieutenants Fowler and Edwards, also marched forward to Mastuj. When Captain Ross arrived at Buni he found that all was quiet, and he therefore returned to Mastuj, with news to that effect. The party of sappers were to march, the next morning, with the ammunition escort.

On the evening of that day a note was received from Lieutenant Edwards, dated from a small village two miles beyond Buni, saying that he heard that he was to be attacked in a defile, a short distance away. He started with a force of ninety-six men, in all. They carried with them nine days' rations, and one hundred and forty rounds of ammunition.

Captain Ross at once marched for Buni, and arrived there the same evening. Here he left a young native officer and thirty-three rank and file while, with Lieutenant Jones and the rest of his little force, he marched for Reshun, where Lieutenant Edwards' party were detained. They halted in the middle of the day; and arrived, at one o'clock, at a hamlet halfway to Reshun.

Shortly after starting, they were attacked. Lieutenant Jones, one of the few survivors of the party, handed in the following report of this bad business.

"Half a mile after leaving Koragh the road enters a narrow defile. The hills on the left bank consist of a succession of large stone shoots, with precipitous spurs in between. The road at the entrance to the defile, for about one hundred yards, runs quite close to the river; after that it lies along a narrow maidan, some thirty or forty yards in width, and is on the top of the river bank, which is here a cliff. This continues for about half a mile, then it ascends a steep spur.

"When the advanced party reached about halfway up this spur, it was fired on from a sangar which had been built across the road and, at the same time, men appeared on all the mountain tops and ridges, and stones were rolled down all the shoots. Captain Ross, who was with the advanced guard, fell back on the main body. All the coolies dropped their loads and bolted, as soon as the first shot was fired. Captain Ross, after looking at the enemy's position, decided to fall back upon Koragh; as it would have been useless to go on to Reshun, leaving an enemy in such a position behind us."

Captain Ross ordered Lieutenant Jones to fall back with ten men, seize the lower end of the defile, and cover the retreat. No fewer than eight of his men were wounded, as he fell back. Captain Ross, on hearing this, ordered him to return, and the whole party took refuge in two caves, it being the intention of their commander to wait there until the moon rose, and then try to force his way out.

But when they started, they were assailed from above with such a torrent of rocks that they again retired to the caves. They then made an attempt to get to the top of the mountain, but their way was barred by a precipice; and they once more went back to the cave, where they remained all the next day.

It was then decided to make an attempt to cut their way out. They started at two in the morning. The enemy at once opened fire, and many were killed, among them Captain Ross himself. Lieutenant Jones with seventeen men reached the little maidan, and there remained for some minutes, keeping up a heavy fire on the enemy on both banks of the river, in order to help more men to get through.

Twice the enemy attempted to charge, but each time retired with heavy loss. Lieutenant Jones then again fell back, two of his party having been killed and one mortally wounded, and the lieutenant and nine sepoys wounded. When they reached Buni they prepared a house for defence, and remained there for seven days until reinforcements came up.

In the meantime the 20th Bengal Sappers and Miners, and the 42nd Kashmir Infantry had gone on, beyond the point where Captain Ross's detachment had been all but annihilated, and reached Reshun; and Lieutenants Edwards and Fowler, with the Bengal Sappers and ten Kashmir Infantry, went on to repair a break in the road, a few miles beyond that place. They took every precaution to guard against surprise. Lieutenant Fowler was sent to scale the heights on the left bank, so as to be able to look down into some sangars on the opposite side. With some difficulty, he found a way up the hillside. When he was examining the opposite cliff a shot was fired, and about two hundred men rushed out from the village and entered the sangars.

As Fowler was well above them, he kept up a heavy fire, and did great execution. The enemy, however, began to ascend the hills, and some appeared above him and began rolling down stones and firing into his party. Fowler himself was wounded in the back, a corporal was killed, and two other men wounded. He managed, however, to effect his retreat, and joined the main body.

As the enemy were now swarming on the hills, the party began to fall back to Reshun, which was two miles distant. They had an open plain to cross and a spur, a thousand feet high, to climb. During this part of the retreat an officer and several men were wounded but, on reaching the crest, the party halted and opened a steady fire upon the enemy; whom they thus managed to keep at a distance till they reached Reshun, which they did without further loss.

The force here were occupying a sangar they had formed, but so heavy a fire was opened, from the surrounding hills, that it was found impossible to hold the position. They therefore retired to some houses, where firewood and other supplies were found. The only drawback to this place was that it was more than a hundred yards from the river, and there was consequently great danger of their being cut off from the water.

As soon as they reached the houses they began to fortify them. The roofs were flat and, by piling stones along the edges, they converted them into sangars. The walls were loopholed, the entrances blocked up, and passages of communication opened between the houses. A party of Kashmir volunteers then went down to the other sangar and brought the wounded in, under a heavy fire.

At sunset the enemy's fire ceased, as it was the month of Ramzam, during which Mahomedans have to fast all day between sunrise and sunset. As night came on the little party took their places on the roofs, and remained there till daylight. By this time all were greatly exhausted for, during their terrible experiences of the previous day, they had had no food and little water.

When day dawned half the men were withdrawn from their posts, and a meal was cooked from the flour that had been found in the houses. A small ration of meat was also served out. During the day the enemy kept up a continuous fire but, as they showed no intention of attacking, the men were allowed to sleep by turns.

After dark Lieutenant Fowler and some volunteers started for the river, to bring in water. They made two trips, and filled up all the storage vessels at the disposal of the garrison. The night passed quietly but, just before dawn, the enemy charged down through the surrounding houses. Lieutenant Edwards and his party at once opened fire, at about twenty yards' range. Tom-toms were beaten furiously, to encourage the assailants; but the tribesmen could not pluck up courage to make a charge and, at nine o'clock, they all retired. During the attack four of the sepoys were killed, and six wounded.

Next night another effort was made to obtain water. Two sangars were stormed, and most of their occupants killed. The way to the water was now opened but, at this moment, heavy firing broke out at the fort; and Lieutenant Fowler, who was in command, recalled his men and returned to assist the garrison.

On the following day a white flag was hoisted, and an emissary from Sher Afzul said that all fighting had ceased. An armistice was accordingly arranged. All this, however, was but a snare for, a few days later, when the two British officers went out to witness a polo match, they were seized, bound with ropes, and carried off. At the same moment a fierce attack was made on a party of sepoys who had also come out. These fought stoutly, but were overpowered, most of them being killed.

The garrison of the post, however, under the command of Lieutenant Gurdon, continued to hold the little fort; and refused all invitation to come out to parley, after the treachery that had been shown to their comrades. The two officers were taken to Chitral, where they were received with kindness by Amir Khan.

The news of this disaster was carried to Peshawar by a native Mussulman officer, who had been liberated, where it created great excitement. As all communication with Chitral had ceased, the assistant British agent at Gilgit called up the Pioneers; who marched into Gilgit, four hundred strong, on the 20th of March. On the 21st news was received of the cutting up of Ross's party, and it was naturally supposed that that of Edwards was also destroyed.

Colonel Kelly of the Pioneers now commanded the troops, and all civil powers; and Major Borradale commanded the Pioneers. The available force consisted of the four hundred Pioneers, and the Guides. Lieutenant Stewart joined them with two guns of the Kashmir battery.

Two hundred Pioneers and the Guides started on the 23rd. The gazetteer states that it never rains in Gilgit, but it rained when the detachment started, and continued to pour for two days. The men had marched without tents. Colonel Kelly, the doctor, Leward, and a staff officer followed in the afternoon, and overtook the main body that evening.

The troops had made up little tents with their waterproof sheets. Colonel Kelly had a small tent, and the other officers turned in to a cow shed. The force was so small that the Pioneers asked the others to mess with them, each man providing himself with his own knife, fork, and spoon, and the pots being all collected for the cooking.

The next march was long and, in some places, severe. They were well received by the natives, whose chiefs always came out to greet them and, on the third day, reached Gupis, where a fort had been built by the Kashmir troops. At this point the horses and mules were all left behind, as the passes were said to be impassable for animals; and native coolies were hired to carry the baggage.

Lisle had enjoyed the march, and the strange life that he was leading. He was now quite at home with his company and, by the time they reached Gupis, had become a general favourite. At the end of the day, when a meal had been cooked and eaten, he would join in their songs round the fire and, as he had picked up several he had heard them sing, and had a fair voice, he was often called upon for a contribution. His vivacity and good spirits surprised the sepoys who, as a whole, were grave men, though they bore their hardships uncomplainingly. He had soon got over the feeling of discomfort of going about with naked legs, and was as glad as the soldiers, themselves, to lay aside his uniform and get into native attire.

The sepoys had now regular rations of meat. It was always mutton, as beef was unobtainable; but it was much relished by the men, who cut it up into slices and broiled it over a fire.

Not for one moment did Lisle regret the step he had taken. Young and active, he thoroughly enjoyed the life; and looked forward eagerly to the time when they should meet the enemy, for no doubt whatever was now felt that they would meet with a desperate resistance on their march to Chitral. Fears were entertained, however, that when they got there, they would find that the garrison had been overpowered; for it was certain that against this force the chief attack of the enemy would be directed. The overthrow of Ross and his party showed that the enemy were sturdy fighters; and they were known to be armed with breech-loading rifles, of as good a quality as those carried by the troops.

In the open field all felt that, however numerous the tribesmen might be, they would stand no chance whatever; but the passes afforded them immense advantage, and rendered drill and discipline of little avail.

Chapter 3: The First Fight

And yet, though he kept up a cheerful appearance, Lisle's heart was often very heavy. The sight of the British officers continually recalled his father to his memory. But a short time back he had been with him, and now he was gone for ever. At times it seemed almost impossible that it could be so. He had been his constant companion when off duty; had devoted much time to helping him forward in his studies; had never, so far as he could remember, spoken a harsh word to him.

It seemed like a dream, those last hours he had passed by his father's bedside. Many times he lay awake in the night, his face wet with tears. But with reveille he would be up, laughing and joking with the soldiers, and raising a smile even on the face of the gravest.

It had taken him but a very short time to make himself at home in the regiment. The men sometimes looked at him with surprise, he was so different from themselves. They bore their hardships well, but it was with stern faces and grim determination; while this young soldier made a joke of them.

Sometimes he was questioned closely, but he always turned the questions off with a laugh. He had learned the place where his supposed cousin came from and, while sticking to this, he said that a good fairy must have presided over his birth; information that was much more gravely received than given, for the natives have their superstitions, and believe, as firmly as the inhabitants of these British islands did, two or three hundred years ago, in the existence of supernatural beings, good and bad.

"If you have been blessed by a fairy," one of the elder men suggested, "doubtless you will go through this campaign without harm. They are very powerful, some of these good people, and can bestow long life as well as other gifts."

"I don't know whether she will do that. She certainly gave me high spirits. I used to believe that what my mother said happened to her, the night after I was born, was not true, but only a dream. She solemnly declared that it was not, but I have always been famous for good spirits; and she may have been right, after all."

There was nothing Lisle liked better than being on night picket duty. Other men shirked it, but to him there was something delightful to stand there almost alone, rifle in hand, watching the expanse of snow for a moving figure. There was a charm in the dead silence. He liked to think quietly of the past and, somehow, he could do so far better, while engaged on this duty, than when lying awake in his little tent. The expanse and stillness calmed him, and agreed far more with his mood than the camp.

His sight was keen, even when his thoughts were farthest away and, three times, he sent a bullet through a lurking Pathan who was crawling up towards him, astonishing his comrades by the accuracy of his aim.

"I suppose," he said, when congratulated upon the third occasion on which he had laid one of the enemy low, "that the good fairy must have given me a quick eye, as well as good spirits."

"It is indeed extraordinary that you, a young recruit, should not only make out a man whom none of us saw; but that you should, each time, fetch him down at a distance of three or four hundred yards."

"I used to practice with my father's rifle," he said. "He was very fond of shikari, and I often went out with him. It needs a keener sight to put a bullet between the eyes of a tiger, than to hit a lurking Pathan."

So noted did he become for the accuracy of his aim that one of the native officers asked him, privately, if he would like to be always put on night duty.

"I should like it every other night," he said. "By resting every alternate night, and by snatching a couple of hours' sleep before going on duty, when we arrive at the end of a day's march in good time, I can manage very well."

"I will arrange that for you," the officer said. "Certainly, no one would grudge you the duty."

One night, when there had been but little opposition during the day, Lisle was posted on a hill where the picket consisted of ten men; five of whom were on the crest, while the other five lay down in the snow. The day had been a hard one, and Lisle was less watchful than usual. It seemed to him that he had not closed his eyes for a minute, as he leant on his rifle; but it must have been much longer, for he suddenly started with a feeling that something was wrong, and saw a number of dark figures advancing along the crest towards him. He at once fired a shot, and fell back upon the next sentry. Dropping behind rocks, they answered the fire which the enemy had already opened upon them.