Полная версия

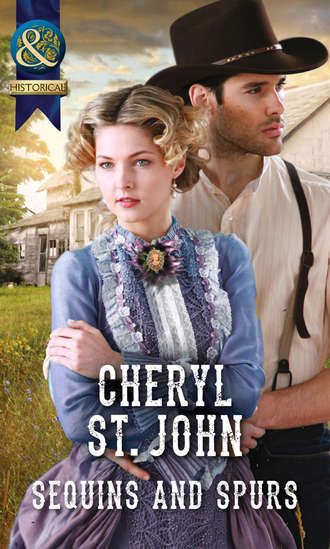

Sequins and Spurs

“My mama always says you can’t learn till you try,” Dugger noted, and gave her an appreciative nod.

The beans were still a little hard. She hadn’t quite figured that out, either. But she could make golden, flaky biscuits with one arm tied behind her back. She’d found honey and poured some into a small jar, which she passed around.

The men didn’t complain a whit about the food, eating as though they’d been served a feast. She got up and poured each of them coffee. “I found a jar of peaches for dessert.”

She had sliced peaches portioned into four dishes when she looked up and noted Nash’s expression. He was looking at the jar with a bleak expression. “Did I do something wrong?”

He shook his head.

“Were these special? Perhaps I should have asked.”

He reached for his dish. “They’re just peaches.”

Dugger finished first. “Thank you for a fine meal, Miss Dearing.”

The others followed his lead and trailed out the back door. The last one to the door, Nash turned back.

She paused in picking up plates and tentatively met his gaze.

“Thanks.” He shut the door behind him.

“That must’ve pained you,” she said to the closed door. She doggedly washed the dishes, wiped the table and hung the towels to dry, before pouring a pitcher of water and heading upstairs, exhausted.

The silent house yawned in the falling darkness. In her mother’s old room, Ruby stripped off her clothing, washed her face and sponged her body before unfolding a cotton gown and dropping it over her head. She touched the fabric, brought it to her face and inhaled, hoping to find a trace of her mother in its clean folds. The scents of lavender and sunshine were pale reminders. She sat in the corner chair and surveyed the room she’d so carefully scrubbed and waxed.

“I’m sorry, Mama.” The silent room absorbed her voice. “I wanted to make it up to you—all the years I was gone. I hoped you’d forgive me and let me try to start over with both you and Pearl.” Ruby let her gaze touch the molding around the ceiling. “If you missed me half as much as I miss you now, I know how bad it was. I’m glad you had Pearl.”

She didn’t want to think about how hard it must have been on her ill mother when Pearl was killed. “Your room looks real pretty. I’m going to get the rest of the house just the way you like it, too.”

When she could no longer keep her eyes open, Ruby stretched out on the bed and fell into an exhausted sleep.

* * *

In the glow of a lantern, Nash opened the stall door and studied the magnificent horse Ruby called the Duchess. It was his job to know horses, and he recognized this breed from a livestock exhibition he’d attended a few years ago. While they weren’t as perfectly proportioned as Thoroughbreds, Barbs were agile and fast, second only to Arabians as one of the oldest breeds in existence. Nash had saved for a long time to buy a Thoroughbred to improve his stock. He knew an expensive horse when he saw one.

Contemplating how Pearl’s sister had come by this one puzzled him to no end. He didn’t know of anyone in the country who bred or sold them. He ran a palm down over the mare’s bony forehead, and she twitched an ear.

Everything he thought he’d known about Ruby Dearing was being turned upside down. Pearl had never spoken ill of her, but Pearl never spoke ill of anyone. A few years after their father had deserted them, Ruby had hightailed it out of their lives as well. What drove a person to leave their family behind and disappear?

He’d been young once, frustrated by his father’s expectations that he work at the mill in hopes of one day taking over. Nash had told his father that he wanted something else—that he wanted to raise horses—but his father had turned a deaf ear. Cosmo Sommerton’s own dream of building a milling operation and leaving it as a legacy kept him from recognizing or appreciating his son’s ambition.

The few times during his youth that Nash had approached his father about going out on his own, Cosmo had become so upset Nash had backed down. He’d still been working at the mill when he was in his twenties. Through church activities he and Pearl had struck up a friendship.

Nash stroked the Duchess’s shiny neck and patted her solid withers. “You’re a beauty, all right.”

The horse nickered. It had been no secret that Pearl and her mother were looking for someone to take over the operation of their farm. They could no longer afford to pay hands to do all the work, and had come to the place where they were forced to sell or combine efforts with another owner.

Pearl had been one of the prettiest young women in the community. She was a sweet thing, devoted to her mother and a volunteer at church. There were plenty of fellows willing to court and marry her, but she hadn’t given anyone the time of day until she and Nash became better acquainted.

Nash had taken his share of girls to local dances, but the idea of marrying one had made his future at the mill less and less appealing. If he had a wife—and most likely a young family—he’d be stuck there forever.

One evening he had shared with Pearl his hopes for having a ranch. After talking to her mother, she’d approached him a few days later with the offer of turning the Dearing farm into a ranch. The land was there, the buildings, even fertile fields for hay and alfalfa. Everything he needed for a start. He’d set aside some savings, which he could use to buy horses.

Nash let himself out of the stall and checked on the mares as he made his way toward the front of the stable.

As he’d pondered it over, knowing without a shadow of a doubt that he wanted that land, he’d considered his father’s reaction. Nash had thought about their future living arrangements—and how everything would be more suitable and proper if he and Pearl married. His father would likely be more tolerant of Nash’s choice if love was involved.

And so he’d proposed, and Pearl had cheerfully accepted. They’d made the best choice for everyone concerned, and Nash had his ranch.

It had been easy to love Pearl. She was kind and loving and never complained, even when he worked long hours and spent nights in the barn with foaling mares. She had Laura for company, and later the children kept her busy.

In his heart, though, Nash sometimes feared he’d cheated her. He’d always planned that there would be time to make it up to her, time when they could take trips and he could lavish attention on her as she deserved.

But the horses always needed his attention. And then Laura had become ill, and Pearl had devoted more of her time to her mother. Nash recalled one evening in particular, when he’d entered the house after dark and Pearl had still been in the kitchen. The sweet smell of peaches hung heavy in the air. A dozen Mason jars sat cooling on the table, and his wife was washing an enormous kettle. She set it on the stove when she’d dried it, and turned to greet him with a weary smile.

“Are you hungry?”

“I ate with the hands.”

“Maybe a dish of peaches then?” One slender strand of hair had escaped the neat knot she always wore, and touched her neck. She tucked it back in place.

“You need your rest.” He stepped close and reached behind her to untie her apron. He hung it over the back of a chair. “Go on upstairs. I’ll bring water.”

The image faded in Nash’s mind. He had more and more trouble remembering their exchanges, especially with Ruby here. Ruby’s vibrant presence overwhelmed his senses.

Was that why he had so much trouble accepting her? Because she made him feel as though he was losing another part of himself? Just by being here she pointed out things he didn’t want to admit.

Ruby had been making a visible effort to ingratiate herself. She had taken some pretty harsh news and done her best with it, all things considered. He couldn’t argue about her right to be here. He didn’t have to approve of what she’d done in the past.

When he thought about the situation like that, he went back over his decisions. What would Pearl want him to do? What would Laura expect? He extinguished the last lantern and looked toward the darkened house.

He owed it to Pearl to give Ruby a chance.

Chapter Six

The following morning, she was awakened by Nash’s voice shouting up the stairs. “Ruby!”

“What did I do now?” she grumbled, climbing out of bed and tugging on a wrapper. She padded to the head of the staircase and looked down. “Good morning.”

He stood in the entryway, looking upward. “Dugger and I are ready to move furniture before we head out to check stock.”

She darted back the way she’d come. “I’ll be right down!”

She had no idea what had changed his mind, but she was thankful. A glance in the mirror made her laugh. Her hair had a life of its own, and mornings weren’t her best. She could only imagine what Nash had thought.

She pulled on one of her mother’s brown skirts and a lightweight shirtwaist, found her shoes and tugged her obstinate hair into a tail.

Dugger handed her a cup of coffee as she landed at the bottom of the staircase. “Nash made a pot. Didn’t know if you like it sweet or not, so it’s black.”

She noted the front door had been propped open with a length of wood. “Black is perfect, thank you.”

She blew on the steaming cup, took a sip and steadied the coffee as she followed him to the parlor.

“How many rooms do you want to do?” Nash asked. “We can carry out the dining room furniture, too, if you like.”

“I would appreciate that. I’ll go take dishes out of the china cabinet.”

He nodded and set to work. Within forty-five minutes, two rooms of furniture had been moved to the porch and the front yard. Her mother’s dishes sat in neat stacks along one wall of the hallway.

“Is there a wagon I can use to bring supplies from town?” Ruby asked Nash before he could leave. “I’ll hitch up my own horse.”

He gave her a hesitant nod. “I’ll move the buckboard out where you can get to it. Might want to introduce your mare to the big bay in the corral. He’s good as the other half of a team. Doesn’t spook easily.”

Because Pearl’s death had occurred when a wagon turned over, Ruby’s question probably stirred up those memories.

“What’s his name?”

Nash gave her a surprised look. “Boone.”

“Thanks.”

He nodded, and he and Dugger headed out.

All morning, Ruby scrubbed and dusted and polished windows. While the wax dried on the floors, she washed up, changed into clean clothing and headed for town. She would much rather have saddled the Duchess and ridden her, but that left the problem of getting things back to the farm. Ranch, she corrected herself.

Fences were in good condition, and the horses in corrals were handsome and healthy. She could see the results of Nash’s hard work everywhere.

Butterflies attacked her stomach as she reached the outskirts of town. She hadn’t been this nervous about going home. There would be a lot of people who remembered her from years ago, and most folks had known her mother and Pearl. As far as Crosby was concerned, Ruby already had a reputation.

One other buckboard sat in front of the mercantile, so she stopped behind it. The bell over the door rang as she entered the store.

“Be right with you!” a man called.

A combination of smells assailed her senses, bringing back vivid memories. Coffee, kerosene, leather and brine combined to transport her to her childhood, when she’d stand beside her mother as Laura made her meager purchases.

Two women, one older, one younger, stood browsing through fabric bolts. Ruby gave the mature one a smile when she looked her way.

“Ruby? Ruby Dearing?” the woman asked.

Ruby nodded, trying to place the face.

The younger one turned at her mother’s exclamation. Ruby did recognize her. “Audra Harper?”

“It’s Reed now, but yes, it’s me.” She laid down the fabric she’d been holding and walked toward Ruby. Her gaze traveled over the skirt that had been Ruby’s mother’s and over her barely restrained hair. “You’re the last person I ever expected to see shopping in the mercantile today.”

Ruby still wasn’t sure of Audra’s reaction to her presence. “I got here evening before last.”

“Do you remember my mother, Ettie?”

“Of course. Nice to see you, Mrs. Harper.”

“Well, I am surprised to see you after all this time,” Ettie said. “How long has it been? Seven years? Eight?”

“About that,” Ruby replied with a nod.

Ettie gave her a sideways look. “Some of us thought we’d see you at your sister’s funeral. Or your mother’s.”

Ruby fished in the pocket of her skirt and pulled out her list. “I didn’t know of their deaths until two nights ago.”

“Shame to lose them both like that,” Ettie said, but Ruby didn’t hear much sympathy in her tone. “Your mother was a wonderful, God-fearing woman. She never missed a Sunday service until she was too weak to ride into town.”

“She always did set store by going to church,” Ruby said simply.

The white-haired man Ruby identified as Edwin Brubeker had finished with his last customer, and now stood listening with interest. She turned and acknowledged him. “Hello, Mr. Brubeker.”

“Hello, Ruby. I would have recognized you anywhere. You haven’t changed a bit, and you strongly resemble your sister.”

“Pearl’s hair didn’t look like that,” Ettie interjected.

“And you’re taller, aren’t you?” Audra asked curiously.

“I wouldn’t know. I haven’t seen her since she was thirteen or fourteen.”

“You’re definitely taller,” Audra assured her, as though it was important that Ruby know.

Wanting to escape their scrutiny now, Ruby handed her list to Mr. Brubeker. “I’ll look around a bit while you put my order together.” She dismissed the women with a brief, “I’m sure we’ll be seeing each other again soon,” and headed for a wall of goods in the opposite direction. She stood looking at small kegs of nails and rows of tools as though they were of extreme interest. She’d wanted a hammer just that morning, so she selected one and carried it to the counter, avoiding meeting anyone’s eyes.

After she’d picked out a few more items, the store owner had her order ready. “On the Lazy S’s bill?” he asked.

Nash hadn’t said anything about paying for supplies, and she hadn’t thought about it. The least she could do was supply these things. “I’ll pay now.”

Mr. Brubeker’s white eyebrows rose. He looked at the cash she placed on the counter. “My grandson will load the wagon.”

“Thank you.” Audra and Ettie were still hovering near the aisle when she turned to go. “Nice to see you both,” she said.

“What are you doing back in Crosby?” Ettie asked.

“Mother,” Audra chided.

Ruby paused only briefly. “I’m figuring that out. Now if you’ll excuse me.”

Mr. Brubeker’s grandson was a lanky redheaded youth with a charming grin and freckles spattered across his nose and cheeks. He was still loading the buckboard, so she strolled along the street, gazing into the windows of the printer, the barber and a locksmith. A commotion at the end of the block caught her attention and she made sure the Brubeker boy was still loading her purchases before walking toward the gathering.

Next to the livery, a small crowd had formed around the corral, where four horses stood listlessly.

Ruby inched her way closer to the barricade to see the animals. They were all appallingly thin, with splotchy coats, and one in particular, a speckled gray gelding, had bare spots on his hide and ribs showing.

“What’s going on?” she asked the men beside her.

“That fella’s tryin’ to sell those horses, but don’t look like he’s gettin’ any takers.”

She observed silently for a few painful minutes. It was obvious the poor animals were undernourished and neglected. Ruby felt sick at first, but then anger swept over her. “Who do they belong to?”

“See the short bald fella over there? Him.”

She skirted the gathering until she reached the man he’d indicated. “Are those your horses?”

He turned and looked at her. She was an inch or two taller and he had to gaze up. His eyes widened. “Who are you?”

She ignored the question. “These horses haven’t been cared for or fed properly.”

He narrowed his gaze. “Who the hell are you and what would you know?”

“My name’s Ruby Dearing, and it doesn’t take a genius to look at their coats and ribs and see they’ve been neglected.” She glanced around, noting the curious faces of the bystanders. “Isn’t there a law to protect those animals?”

A couple men shrugged.

“Well, little lady. If’n you’re so fixed on the critters, why don’t you fork over the cash to buy ’em and take ’em home?”

Ruby’s skin burned hot. She shot the gathering of men a challenging look. “I’ll buy one if the rest of you will buy one.” She turned back. “How much are you asking?”

“Fifty dollars apiece.”

The man was both cruel and a crook. She looked him in the eye. “You’ll get ten dollars a head and not a cent more. Take it and leave before I find the marshal.” Reaching into the deep pocket of her skirt, she pulled out her coin purse and plucked out paper money. Casting a challenging stare at those around her, she urged, “Don’t let him get away with this. Take a good look at these mistreated animals. Someone has to do something. Buy one of these horses or you won’t be able to sleep tonight for the guilt of not doing what’s right.”

Grumbles arose, but three of the men produced money. One by one they begrudgingly selected their horses, until only one was left standing. Ruby shoved her ten dollars at the seller and marched forward. “What’s his name?”

The man glared at her and stuffed the money into his pocket. “Call the hay-burnin’ bag o’ bones any damned thing you want.”

He turned on his heel and stormed into the livery.

Ruby stroked the gelding’s neck and looked him over. He rolled his eye at her and bobbed his head. Patches of his hide were raw and he had sores on his legs. Her eyes stung at his suffering. The animal’s obvious misery turned her stomach.

Those who remained near the corral watched her. She took the horse’s lead and walked him from the enclosure, hoping he had the gumption to make it back to the ranch.

The buckboard was loaded, so Ruby led the gelding to the trough, let him drink a minute and then tied him to the tailgate. After climbing up to the seat and unhooking the reins, she spoke to the Duchess and Boone. “We’re heading back real slow. This fellow needs a good home.”

Once outside town, she stopped the team, got down to untie the gelding and let him graze in the shade of a tree for a few minutes. Back on the road, she turned and checked on him often as they made plodding progress.

Finally reaching the ranch, she drove the buckboard to the house.

Dugger had seen her approach, and joined her to unload the items. “Where’d the gray come from?”

“I bought him from a man in town.”

“Looks mighty sickly, don’t he? I’m surprised he made it all the way here.”

“Me, too.” She untied the gelding and led him toward the stables.

Nash appeared at the corner of the building and faced her with feet planted. “What are you doing?”

“I’ve brought home a horse.”

“I can see it’s a horse. What’s it doing here?”

“I bought it.”

“You paid for that animal?”

“He was in a bad situation, and I wasn’t going to leave him behind.” She stroked the horse’s withers and stepped nearer his head to rub his bony brow.

Nash’s expression didn’t reveal his thoughts. He looked at the horse for a long moment. “You’ve taken on a big job.”

“He’s had a hard life. I’m going to take care of him.”

“And just how do you plan to do that?”

“Well, feed him, first off. I’ll give him plenty of oats and water.”

Nash shook his head. “Can’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“This horse is malnourished. He’s not used to eating. Feeding him as you would any other horse would kill him.”

A bolt of concern rocketed through Ruby’s chest. “I let him eat grass on the way home!”

Nash’s expression softened. He visibly relaxed his shoulders. “Grass is fine. Hay, too. But no hard grains. You’ll have to start feeding him slowly, making mash like wet slop at first.”

“Out of what?”

“Soybean meal, linseed meal. It’ll have to be ground until his stomach and intestines get used to it.”

“Ground. Could I use the coffee grinder?”

“Don’t see why not.” Nash watched her stroke the animal’s neck. “Bring him inside, then get the grinder. I’ll show you.”

Nash didn’t know what to make of this woman bringing home a badly neglected horse. It seemed she’d made herself right at home—and she was; he couldn’t deny it. The land was legally hers. The agreement between him and her mother had been a verbal one. At the time Laura had been weak, but they’d all assumed Pearl would be here to retain the property and house.

Watching Ruby with the horse, recognizing her instinctive need to help the animal, played havoc with Nash’s knowledge of the woman. What was a footloose and fancy-free honky-tonk singer doing caring about the fate of an abused animal? He didn’t like this chip in his already polished opinion.

She headed for the house and returned carrying a big wooden coffee grinder with a cast-iron crank.

“Take the drawer out and set it over a pan in the back there,” he told her. “I’ll take him to a stall.”

Nash led the docile horse away, and Ruby did as he asked. When he returned he scooped soybean meal into a bucket and scooted it toward her. She cranked while he went for a pail of linseed meal.

When she changed hands, he realized her arm must be growing tired, but she was relentless. “Let me do the linseed,” he offered.

“I can do it,” she insisted.

“We still have the rugs and furniture to put back,” he reasoned. “I can do this faster.”

She relented, but knelt close to do all the scooping.

After several minutes of silence he looked at her. “I have to ask. How did this horse purchase come about?”

“I was waiting for Mr. Brubeker’s grandson to load the things I bought, and I saw a gathering at the livery. I was curious, so I walked over. A man had four horses he was trying to sell. They were all skinny and their coats were in bad shape. This one was the worst.”

“And so you bought him?”

She tucked her hair behind her ear, glanced away, but then looked back at him. “Yes. I couldn’t watch that man any longer, and I couldn’t let him get away with mistreating those animals.”

“What about the other horses?”

“Some of the men there bought them.”

Getting to his feet, Nash studied the ill-treated animal and tried to picture the scene, but couldn’t. He certainly didn’t fault Ruby for her compassion, but she’d taken on a big job. “This should be enough food to last a few days. We’ll make a pailful at a time. Want to dip water?”

“Sure.” She got to her feet and soon returned, lugging a full pail.

Nash got a long wooden stick from the tack room and together they poured water and stirred. “Real thin,” he told her. “Then you have to let it stand and expand for a few minutes before you feed it to him. Otherwise it’ll swell in his belly.”

While they waited he went for a salt block and set it in the stall. At the front of the stable Dugger could be heard unharnessing the horses.

At last Nash carried the pail in for Ruby, and together they watched the animal lower his head to the slop and eat.

“And he can have grass, too?” she asked.

“Hay, grass, alfalfa,” Nash said. “You can’t let him out in the pasture for a couple of weeks. His intake has to be moderate until he’s doing well with this.”

She met Nash’s eyes. “You sure know a lot about how to take care of him. I would have done it all wrong and caused him harm.”

Her comment flustered Nash, but he didn’t let on. “Tomorrow you can wash him down. Then treat those sores.”