Полная версия

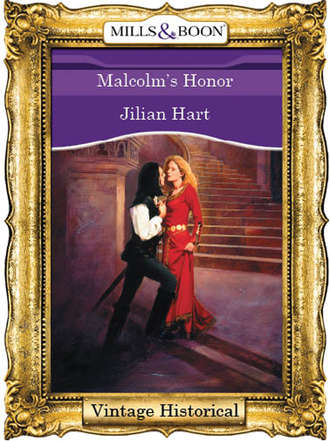

Malcolm's Honor

He heard the censure in that and chose to remain silent. She had returned of her own accord—why, he could not fathom. Surely not to heal a fallen man, one she had not thought twice about kicking like an angry donkey. Yet Malcolm could not deny her touch was tender and her intent to heal sincere. She stitched and cleaned, studied her work, then stitched some more. Beads of sweat dotted her forehead and dampened the tendrils of gold gathered there, curling them, though the night was cold.

He could not deny how hard she worked. And for what? This daughter of a traitor ought to be bound like her father to a tree. She ought to fear for the crimes she faced. And yet she saw only Hugh and uttered commands to the old woman as if she were a king at war.

Light brushed her face, soft as the fine weave of her gown and cloak, stained by travel. ’Twas a pretty face, not beautiful, but striking. She had big, almond-shaped eyes, blue like winter, direct, not coy. Long curled lashes, as gold as her hair, framed those eyes. He admired her gently sloping, feminine nose. And her mouth! God’s teeth, ’twas bow shaped and as tempting as that of the moon goddess herself.

Then Elin sighed, a soft release of air, all emotion, all sadness. Her unblinking gaze collided with his directly; there was no flirting, no shyness, no feminine submission. “I fear there is more damage than I can repair, but the wound, both inside and out, is closed.”

He swallowed. “Hugh will die?”

“There’s no fever yet.” She laid a small hand to the unconscious knight’s forehead. “A fine sign. Now we must pray he is strong enough. I will do all I can.”

“You will, because I command it.” She may have returned of her own volition, but Elin of Evenbough was his prisoner still. He would not fail his king.

A smile tugged at one corner of her mouth, and that defiant chin firmed. “Again you try to terrify me, a woman half your size. Always the valiant warrior.”

Anger snapped in his chest and he held his tongue. She challenged his authority; she rebelled at something deeper. He was, as she said, twice her size and twice her strength. And he had her knife—her last one, he guessed—in his keeping. The only weapon left her was her tongue, and he could withstand those barbs. And if not, he would gag her, as he had her betrothed, the treacherous Caradoc.

“Old woman.” He caught the crone’s gaze, and she trembled at the attention. Though old and stooped, she possessed a strong set to her jaw, too. “See that your charge tends the injured men, mine and those captured. But not her father. Let the man suffer like the men he left to die.”

“Yes, Sir Malcolm. I will see the rebellious one obeys.” Head bowed, she scurried away.

Malcolm stepped away into the darkness. The wee hours of morning meant there would be little, mayhap no sleep for him before dawn. And then another day of raising his sword for the king.

Elin of Evenbough had the freedom to speak as she wished, whether innocent or criminal. But Caradoc was right. Malcolm was a peasant born, a barbarian king’s bastard, and both peasant and bastard he would always be. A savage hired merely because he was useful. Useful until another took his place, his livelihood or his head.

He thought of Caradoc’s threat, thought of the unrest of ambitious knights wanting to lead, thought of Elin’s courage in returning to aid her captors.

Lavender light chased the gray shadows at the eastern horizon. ’Twould be another day without peace, without rest, watching his back for treachery and the road ahead for danger.

The lot of a knight was a hard one, but Malcolm was harder.

“Caradoc!” Elin dropped to her knees before the bound man, neighbor and friend to her father. “I do not believe my eyes. What have you done? Challenged the king’s knights and lost?”

He colored from the collar of his hauberk to the roots of his dark hair. “Aye. Your father—”

“You are in league with my father?” she yelped, lowering her voice so it would not carry to the watchful knight keeping guard. That Giles, he looked untrustworthy, far more threatening than poor spying Hugh had ever been.

“Nay, I am no traitor. I would never turn against the king. I came for you.”

“Me?”

“My future bride.” Triumph glittered in his cold eyes.

“’Tis news to me.” She fought to sound unaffected. Surely this man dreamed! By the rood, she would no more marry him than Malcolm le Farouche.

“Your father and I had exchanged words on the matter.”

“We are not betrothed and you know it, Caradoc.” She swiped a clean cloth through the steaming trencher.

“We could be.”

“You only covet my father’s holdings, else you would not risk your life, your freedom and your barony.”

“Your father offered you to me.”

“I am not a cow to be bought and sold.” She brushed at the bloody but shallow cut beneath his jaw. “Look at this wound. Put there by le Farouche’s sword.”

“Loosen my bonds and I will kill him for you. For your honor.”

“Do not do my name that injustice. You would kill him for your uses, not mine, if you could.”

“He defeated me unfairly.”

“Most likely the unfair warrior was you.” Elin knew Caradoc, not by rumor, but from experience. He despised her, as she did him. Worse, she was afraid of him. Hard and dark were his eyes, not lethal like Malcolm’s, but colder still, like a man who killed for pleasure.

As she thought of Malcolm, she looked up and saw him, a fierce knight shrouded in darkness and shadow, standing away from the shivering light of the fire and torch, alone with the night. He had removed his helm, and the wind moved through his long tresses, which were as black as the night. His gaze fastened on hers, and she read his suspicions like a thought in her own mind. As if he were part of her, or she part of him.

Traitor. Malcolm thought her guilty of her father’s crimes. She shivered inside as he strode toward her. He moved like a predator, with silent, powerful strides, until he towered overhead, all tensed male might.

“Do you conspire with this man, this suspected traitor?”

She blanched. “Caradoc is no traitor! Do you accuse every man, woman and child?”

“Silence. I forbid you to speak further with this unworthy lord.” Le Farouche’s lethal look came as a warning.

Yet two different responses sparked to life in her breast. Fear, because she knew Alma was wrong: the fierce knight had his own dark agenda, and Elin knew now to be wary of it. And a light, hot flutter of attraction, because his steely presence stole the very breath from her lungs and stilled the blood in her veins. She fought this response to him. No man of war and killing could attract her. Not even a man this compelling, this beautifully made.

“’Tis just as well, for I will have naught more to do with Ravenwood.” Let le Farouche think she was following his bidding. She had her own reasons for keeping distance between herself and Caradoc. “May I tend my father now that I have treated all other manner of men?”

“You have yet to tend me.” Brows arched across his blade-sharp gaze.

“I refuse to touch the likes of you.” Elin lifted her chin, certain now of the danger she was in. “Even a lowly woman unable to bear weapons has her standards.” She rose.

The fierce knight towered over her, as immovable as a great stone mountain. His mouth twisted when he spoke, mayhap in anger. “Tempt me any further, maid, and I will care naught for your skills to heal, and bind you to a tree like the rest of the traitors.”

“Then bind yourself as well, for you keep to your own agenda in holding captive whomever you come across, be it lord or unarmed woman.” She balanced the trencher so as not to spill it. Curls of steam rose in the chilly dawn air. “I will tend my father.”

“I say you shall not.” His grimace flashed in the waning darkness. “Try me no further.”

“What will you do? Slay me here in the road? ’Tis better than waiting for the same fate in London.” Fear trembled through her, for she was no fool. She heard both anger and truth rumbling in that voice.

“You think I will strike you down?” he roared. “Have I raised my sword to you? Have I struck you? Ravished you? Given you to my men to suit their pleasures?”

She felt small as his wrath filled him, making him seem taller, larger. The air vibrated with his keen male power, and she shivered. “I cannot say you have.”

“Nor will I, on my honor.” He spat the words, and fire-light caught on the steel hilt of his sword, glinting with a reminder of his undefeatable strength. “You have endured no more than being carried from the woods and forced to ride with us. Do you think your betrothed, Ravenwood, would be less cruel?”

“He is not my betrothed,” she declared savagely. If she married the man, ’twould be like ordering her own death. “Never call him that to my face.”

“The maiden warrior is not so easily bent. Do you not fear me?”

He leaned close. She saw the flash of black eyes and white teeth and the hard demanding countenance of a man used to leading battles, of a man used to facing death. She shivered again. “I both fear and loathe you, sir.”

“A true answer, at last. I despise liars, dove. And the company they keep.”

“As do I.”

“Then keep this in mind.” His gaze bored into her, as sharp as any dagger. She stepped back, but he followed, intent upon dominating her as a wolf stalks wounded prey. “I despise your sharp tongue and your rebellious ways, and ’tis clear your father failed to beat you properly.”

“Beat me?” She seethed. What was this? “A knight such as you would surely think violence is the greatest teacher.”

“What I think matters naught. Only how the king judges you. Keep this in mind, fighting dove. I tell no lies to my king. If Edward asks if you fought, if you lacked respect, if you gave any indication you were guilty, then I will tell him what has transpired between us.”

“You would condemn me either way.”

“Nay. Only you have that power.”

She shivered yet again. The threat of such a future felt real for the first time. In Malcolm’s eyes, she could see the grim reality ahead. Would she truly be seated before the king and judged a traitor?

“I am a terrible daughter for certain,” she confessed. Everyone from the lowliest peasant farmer to the highest knight would agree. “But I am loyal. To friend, family and country. Believe me, or condemn an innocent.”

One corner of his mouth quirked. “I am not your judge, Elin of Evenbough.”

“Do you mock me?” There, on his bloody swollen lip, shone the barest hint of laughter. “Does talk of an unjust traitor’s punishment amuse you?”

“Nay.” That humor waned, as silent as the night. “You amuse me—the cruel world does not. Take care in how you act from this moment on. You have tended my men. That will serve you well in the king’s court. I will tell how you worked of your own free will until day’s light without food or water or rest.”

“I came to tend Hugh. I shall not have a dead man on my conscience. I returned to care for his wound, not to prove my innocence or earn a better judgment from the king.”

“You ought to worry about proof, or you will watch your entrails be cut from your body as they draw and quarter you. I have seen enough of such punishment to know it one of the cruelest. You will be alive when they begin butchering you. Remember, innocent or guilty, all that matters is proof of innocence.”

“And I have no proof, no lies to cover, no one to bribe, no way to show I know what my father plotted.”

“You know he plotted?”

“He plots constantly. And as he sits weeping there in the shadows, he still plots a way to escape.” Tears knotted her throat and she fell silent. Anger, fear and an enormous chill of betrayal cloaked her body. What had her father done, involving her in his escape? Had she known he sought to evade the king’s protector, she would have held fast to her bedpost and refused to let go.

Now she would face court. With no way to prove her innocence, save Caradoc, the king’s nephew, trussed up to an oak tree. She could not ask his help. Not from a cheater, a killer and a wife beater. To enlist his aid would mean she would have to agree to his outrageous claims of marriage.

What she needed was a plot of her own. She needed to avoid the king’s court, Caradoc’s influence and the strong sword of Malcolm le Farouche. Already the lavender tint to the horizon began fading to peach. Soon the sun would rise, and they would journey toward London and her fate as a traitor’s daughter.

An idea came to her, and she could not take time to think through the consequences. Being kind to the fierce one would not be easy, though she vowed to do it. For both her life and her freedom. “You bleed, sir.”

“What? No insults? No name-calling? Not ‘sirrah,’ or ‘cowardly knave’?”

Let him mock her. He might be twice as strong, but she was twice as smart. “Nay, I must apologize for my disrespect. You speak truth. I have a rebellious nature, but I have neither the power nor the will to conspire against the king. I will seek to show from this moment forth that I am innocent, and each action will prove this to you and to the king.”

“Well chosen. I will do all I can to aid your cause, for you have given all to tend my wounded men.” The frown faded from his mouth. Though he did not smile, she saw a glimmer of kindness, another puzzle to this man of steel and might. “How fares Hugh?”

“He lives yet.” She selected a clean cloth from the many slung over her shoulder and dipped it into the trencher she held. She stepped close to him—close enough to inhale his night forest and man scent, to feel the heat from his body and see the stubbled growth on his jaw. She dabbed at the cut to his lip and he winced, but did not step away. “Hugh cannot be moved.”

“We cannot remain here.” He gestured with an upturned palm at the road.

“To move your knight is to kill him. He must remain still for the stitched wounds inside to heal. Else I guarantee he will bleed to death. I recall a village not a league from here. It must have an inn. I believe Sir Hugh can travel that far.”

Malcolm caught her hand, his fingers curling around her wrist and forcing the cloth from his face. The power of his gaze, unbending and lethal as the steel sword at his belt, speared her.

“Is this a plot?” he demanded. “Are you attempting to fool me into a trap you and your lover have devised?”

“Lover? You mean Caradoc?” Outrage knifed through her. “What has that addlepated knave told you?”

“Only that he is your betrothed.” Was that amusement she saw flash in his dark eyes?

“As I said, ’tis untrue. He covets my father’s holdings. Seeing him bound like a scoundrel gives me great pleasure.”

Malcolm laughed, the sound rich and friendly this time, not mocking. “You need not tend my wounds, dove. They will heal in time. Day breaks. See to Hugh and prepare him for travel. We will leave him at this inn you know of. If I spy any act of treachery, I will chain you to the wall of the king’s dungeon myself.”

Aye, but you will never be able to find me. Fear trembled through her, and yet she forced a smile to her lips. Her heart thumped with some unnatural reaction to this man of sword and death, dark like the shadows even as the sun rose and brought light to the world.

Chapter Four

A sense of doom settled in Malcolm’s chest as he watched three of his knights lay an unconscious Hugh upon a rickety bed covered in fresh linen. He did not care what the traitor’s daughter predicted. They had brought Hugh here to die.

Malcolm could not stomach how he’d failed the young knight, who’d often proclaimed his eagerness to serve his king and fight beneath the Fierce One’s command. Bitterness soured Malcolm’s mouth.

“I’ll need hot water. You—” Elin pointed a slim finger at one of his men “—see to it.”

“Dove, these are my men to command. Lulach, Hugh needs fresh water. We cannot send the traitor’s daughter for it.”

“True.” Anger burned in resentful eyes, for Lulach, as Malcolm suspected others did, blamed Elin and her father for Hugh’s injuries. “I’ll go, but make no mistake. I’m no criminal woman’s handmaiden.”

Malcolm watched Elin of Evenbough blanch, and saw the denial sharpen her face. She muttered something beneath her breath—and he knew he would have objected had he heard it—then she knelt gracefully at Hugh’s side.

The poor knight’s chances were not good; Malcolm knew this even before she rolled back layers of wool and linen. A neatly stitched gash stretched from Hugh’s ribs to his groin. She bent to study it, her golden hair, with a hint of red, like a flame that caught and shimmered in the sunlight slanting through the open door. She was liquid fire, and when she tilted her face up to meet his gaze, his chest burned as if a firestorm raged there, wicked and untamed.

“I see no sign of fever. Look, no redness marks the edges of the wound.” A measure of joy filled her voice. Not triumph or pride, for Malcolm knew those well enough, but gladness. And her gladness surprised him. “I predict Hugh will live.”

“Do you always predict what you cannot control?”

“What? You doubt my abilities?”

“Aye, I doubt all women.” The girl was too green. She’d not seen death and dying the way he had. A gray pallor clung to the wounded man’s face and took hold, growing stronger as the light shifted and deepened.

“Truly, a man such as you sees naught but dying. What do you know of the living?” She turned her shoulder to him, as if he’d insulted her.

He could not argue. For once the dove was correct.

“Where’s Alma?” Her low voice wobbled a bit.

“I sent her to aid the innkeeper’s wife, who is crippled with joint pain. They are not accustomed to receiving so many men at once. ’Tis a small village, and these roads not often traveled. Only a traitor evading the king’s knights might choose this path.”

“You needn’t remind me of my plight.” Elin bowed her head, searching through the satchel she carried. Crocks clattered together, and the dull clunks and thunks chimed noisily in the somber tension of the air. “Bring me Alma.”

“Nay, dove. If you need assistance, I shall give it.”

“You?” Her eyes widened, and she lifted one corner of her mouth in disbelief. Then, mayhap remembering her vow to behave, she erased that sneer from her delicate lips, pearled with early morning light. “You admit you know naught of healing.”

“I can hold a trencher well enough.” He hid his chuckle behind a cough, amused at her valiant effort not to insult him. Aye, the poor girl was trying, but like an untamed horse facing the prospect of a saddle, she could not hide her unwillingness. “Besides, you are my prisoner. I’ll not leave your side, traitor’s daughter.”

Temper flared in her eyes, glaring like sunlight on water. Her fists curled, but no anger sounded in her voice. She was like any woman, always pretending. “I will honor your offer of assistance, for you are the greatest knight in all the realm.”

“Not so great.” He waited, and although he sensed them, no insults spewed from her sharp tongue. He accepted the trencher of steaming water Lulach handed him. “I’ve seen many manner of men, dove, and not one has been so noble as to bear that title.”

“In this we agree.” She tapped herbs into the water, her gaze avoiding his. “Do you think the king will believe Caradoc’s claim?”

“I cannot say. The king has a mind of his own, though he’s known to be fair. It depends on your father. Whether he chooses to speak the truth, or if he is swayed by Caradoc’s false promises to help save him.”

“Caradoc, aye, he is my fear.” She dipped the cloth into the trencher, leaning close. Her delicately shaped mouth frowned as she worked, and with it her entire face. Soft lines eased across her brow and crinkled at the corners of her eyes. His gaze flickered across the cut of her lips.

Aye, she was young, far too spirited for his taste and much too soft. Yet his chest tightened, and air caught with a painful hitch between his ribs.

“Caradoc is a man of much weakness, many lies,” he admitted.

“What? You believe me? That I am not betrothed to him?” Her measuring gaze latched on to his.

He could see the intelligence in those eyes, the thoughts forming behind them. “I know the like of Ravenwood far too well. I’ve seen many brutes of that ilk.”

“He’s nephew to the king.”

“Aye. I’m well acquainted with that fact.”

Hugh murmured, as if fighting to awaken. Malcolm reached for his hand so the young knight would know he was not alone. But Elin’s fingers were already there, and her compassion glimmered, as unmistakable as the steady glow of sunlight into the dim room. Hugh quieted, and she continued her work bathing his wound.

“Then he will awaken?”

“Aye.” She cast Malcolm a mischievous smile, quick and fleeting. “You doubt my knowledge, but you’ll soon see. Hugh will live.”

“Then he’ll owe his life to you.”

“Nay, to Alma. She pecked like a troubled conscience until I had to return to aid him.”

But Malcolm knew the truth when he saw it. “Nay, I think you returned to aid your betrothed.”

She sparkled with humor. “Go ahead, tease. You shall see what a sacrifice I made in returning, once you spend an entire day with Caradoc. Your knights are likely to behead him just to stop his insults.”

“Does he cast an insult more sharp than yours?”

She almost laughed, and with the sunlight alive in her fiery curls, she was transformed before his eyes into a nymph of beauty and mischief. “I admit I studied Caradoc’s skill, for although I hate the man, I do admire his foul temper.”

“’Tis a skill you practice then? Like wielding a sword?”

“Aye. I am a woman who does both.”

He laughed. How this girl-woman amused him. He’d not been amused by much in more years than he could count. He handed her a fresh bandage when she gestured for one. “Caradoc is trussed up in the stable under guard. At last report, he still had his head.”

Elin gazed at Malcolm with that fire flickering in her eyes, as mesmerizing as a mirage in the desert, when heat and earth and imagination created illusions. “Will the king judge me innocent of treason, but condemn me in marriage to his nephew?”

“’Tis more likely than Edward deciding to have you hanged, drawn and quartered.” A warning twisted in Malcolm’s guts and prickled along the back of his neck. “As long as you continue to prove your innocence to me, you will live.”

“You are not my judge.”

“Nay, but I am your jailer.”

But not for long. Elin thought of the dried oakwood tucked into a pouch in one of her herb crocks. Even a small amount of the berry could render a grown man ill for hours. Ill enough to allow her escape.

Malcolm caught hold of her hand, his big callused fingers rough and strangely fascinating as they covered hers. “Quit your worries, dove. Edward will be pleased that you saved young Hugh’s life.”

For a brief instant she saw behind the heartless eyes, to the ghost of the man he must have once been before he turned killer and traded his soul for the coin it would bring.

’Twas almost a shame she’d have to poison him. But death or marriage to Caradoc? She would not go quietly toward either darkness.

“The crone is serving Giles and the prisoners in the stable. The innkeeper’s wife could not do it.” Lulach settled on the bench and quickly drained the tankard of ale. “I must hurry, ere the old woman begins a plot to free the traitors.”

“Rest and eat, the crone will cause no trouble.” Malcolm took his eating knife from his belt. “’Tis the younger one we must watch.”

“She is a witch, that one. Able to defeat us with her spells and powers.”

“Nay, she’s no sorceress. Look how she works.” He gestured to the young woman emerging from the kitchen, steaming trenchers in hand, her fine wool mantle shivering around her slim thighs with every step she took.