Полная версия

You Will See Fire

All that summer, for the priest, the warnings kept coming. One day, returning home, he found someone had hurled a large rock through a window of his house. Another day, a friendly Kenyan contact—a game warden or policeman—came surreptitiously to say, A decision has been made to eliminate you. Another day, he opened a letter that had arrived in his mailbox and found an unsigned threat in Swahili: Utaona moto. You will see fire.

Much later, Francis Kantai, one of his catechists—a young Masai he had enlisted as a helper and a cultural bridge to the local people—would describe the priest’s sudden unease as he opened the letter. What is it, Father? What does it say?

As Kantai recalled, the priest gave a curt reply—I don’t give a damn—and took the letter down the hall to his room and closed the door. The threat was apt. Fire had been the medium of terror in village after village, defenseless thatched-roof huts and wooden hovels transformed into the tinder of infernos across the countryside. Flames took them quickly and completely. Even in his house of brick, there was little protection against a torch in the night.

It’s easy to imagine that the priest sat on his bed and prayed, clutching that note. It’s possible that he brooded, too, on his young Masai catechist, who slept down the hall from him. To many of the priest’s colleagues and acquaintances, why he permitted Kantai’s presence was a mystery. He was widely believed to be a spy for Sunkuli, and he had confessed to burning houses for the police. The priest had repeatedly defended Kantai, had once even smashed a table in rage when his name was impugned.

By this point, however, there were signs that he had begun to distrust Kantai himself. His housekeeper, Maria, told him that Kantai had let Sunkuli’s men into the parish house, into the priest’s room—the place where he allowed no one, the place where he kept his papers.

The priest had asked a Kenyan friend, Can Francis hurt me?

The friend had responded with a Swahili proverb: Kikulacho kimo nguoni mwako.

It meant: The bug that bites one’s back is carried in what one wears.

IN THE THIRD week of August, the rains came and the grass greened, and from his veranda he watched the cows dance.

One of his catechists, Lucas, handed him an envelope.

A letter for you, Father.

The priest opened it. It had been hand-delivered all the way from Nairobi, passed between church assistants. It was a summons from an authority he could not refuse—Giovanni Tonucci, the papal nuncio, the Pope’s representative in Kenya. The priest was to report to him immediately. The matter was apparently urgent, though unspecified.

Kaiser was certain what the meeting would entail. He would be thanked for his years of service in Kenya, and told to return to the United States to take an extended rest. It would mean, he was sure, his departure from the country for good. He would have to obey. Thirty-six years, and now it was over.

What he did in the days that followed would invite the most exacting scrutiny, his actions weighed and analyzed and puzzled over, his phrases parsed, word by word, and subjected to dramatically different readings. After the summons, his mood changed. He wept at Mass. He asked for prayers. He grabbed his duffel bag, then climbed into his truck with his ax and his rosary beads and his Bible and his neck brace and his shotgun, disappearing down the red-dirt road on the half-day trip to Nairobi.

2

THE LAWYER

THE LAWYER’S PHONE started ringing early that morning. They’ve killed Kaiser. He was at home in Ngong, on the outskirts of Nairobi. He felt a chill spread between his shoulder blades. The first details to reach him were vague, secondhand, filtered through a network of informants whose voices were tight with panic. It was August 24, 2000, four days after Kaiser’s departure from his parish house, and his body had been found in a weedy ditch that morning in Naivasha, about forty miles outside the capital. Nobody could determine what had brought him there. People were saying that his head had been blown apart, that his own shotgun lay nearby.

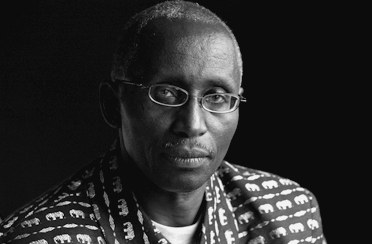

Charles Mbuthi Gathenji was fifty-one, a man of stocky build and medium height. He had a thin mustache, thinning gray-black hair, and sharp cheekbones. He possessed an air of wary circumspection informed by decades on the wrong side of a police state. His eyes were deep-set and heavy-lidded, and his thin, rimless glasses contributed an aura of scholarly gravity, an impression reinforced by his careful, formal English, his accent thickly Kenyan and punctuated with phrases like “It is quite in order.”

He did not deviate from his daily routine on this day. He put on his suit, picked up his leather briefcase, and steered his Mitsubishi Pajero into the cacophony of the capital’s morning gridlock. He had an appearance at the High Court and some appointments at his office. But the sense of prickly unease that had never entirely left him these past few years was very close now. They’ve killed Kaiser. In recent weeks, under the employ of the Catholic Church, the lawyer had been preoccupied by a case that felt eerily similar—the slaying of an Irish monk named Larry Timmons. The monk, not nearly as well known as Kaiser, had accused a Rift Valley policeman of demanding bribes, and one night the cop had shown up at the mission house—in response to a robbery—and shot him to death. A terrible accident, authorities said, but after all, it had been so dark. Now, three years after the shooting, Gathenji was arguing to bring murder charges against the cop; they were in the thick of a protracted inquest, and his witnesses were slowly dismantling the official narrative.

When Gathenji returned home that evening he turned on the television news and got a glimpse of the scene where Kaiser had been found. There was the priest’s body, with its fringe of white hair, supine in the weeds, clad in light gray slacks, black leather shoes, and a leather jacket. There was his Toyota pickup aslant in a drainage culvert, with a twisted right front wheel. There was the interior of the dirty cab, with the priest’s rosary beads hanging from the steering wheel and the sharp edge of his ax visible under some clutter. There were the dark-suited plainclothesmen and black-hatted officers milling around the truck in the sharp country sunshine. There was the shotgun—wrapped, ineptly and incompletely, in police plastic. There was the large crowd of onlookers massed on a nearby berm, mothers standing with arms crossed and children sitting at their feet in the brownish red dirt, all watching wordlessly and immobile as statuary. There was the sky as it had been that morning, pale blue and clear beyond the towering, slender-branched fever trees, and the road already alive with zooming buses as the body was wrapped and loaded into the back of an official Land Rover.

For the last five years, their lives had been closely linked, the lawyer’s and the priest’s. Kaiser would materialize at Gathenji’s office unannounced, always on a crusade, always in dusty shoes. To call ahead of time would have increased the possibility of being followed. He’d bring in people from his parish who needed legal help. He’d scribble notes on newspapers or whatever was on hand. He’d seek advice on how to build cases against government men, and how to get supplies to refugees displaced by violence.

If the Church remained one of the few institutions in Kenya that had raised its voice against the government, it did so mostly in a carefully hedged and muted way. As a corporate body, it preached reconciliation but rarely went further. The American priest had been an exception: He’d named names, and looked for every opportunity to do it again.

As Gathenji saw it, over their years of working together, their bond had evolved into something more profound than mere friendship. They shared the understanding of two colleagues who knew for a certainty that their work could get them killed. They were brothers in a foxhole.

Temperamentally, they were poles apart. Kaiser had a hard-charging, elbows-out approach, always racing toward the cannon’s mouth. Dogged but not personally flashy, Gathenji was quiet, methodical, and preferred to operate behind the scenes. He had a wife and two children. Despite his high-profile battles with the powerful, he tried to speak through his legal work. He saw no reason to draw more attention to himself than necessary.

Many of his peers had cultivated political connections and made themselves rich. He did not view the law as a stepping-stone for political power; to him, his country’s politics had a rank taste. He wasn’t an editorial writer or a maker of screeds and fiery speeches. He seemed to know everybody but made it a point to avoid social clubs. He would not be found mingling with the nation’s legal stars on a Nairobi golf course. He couldn’t be mistaken for a member of the wabenzi class—the Swahili term for those possessed of a Mercedes-Benz, the badge of arrival. He stayed away from bars and made it a habit to be home on his small farm, with his family, well before sunset.

Much of his work, championing the victims of political violence, carried small financial reward. And so despite being one of his country’s best attorneys, he labored in what he characterized as the lower-middle class. He described himself as a simple man, a working lawyer with a Mitsubishi and, when he could afford it, a clerk. He thought of himself as a foot soldier, and had the instincts of a survivor.

For years, he had worked from a respectable fourth-floor office in a tower across the street from the Central Law Courts in downtown Nairobi, but the place had stopped feeling safe a year back; one of Moi’s ministers had moved into the floor below, and Gathenji nervously found himself passing the man’s security detail in the stairway.

Now, in the summer of 2000, he was in semihiding in an old, peeling, out-of-the-way office bungalow on Chania Road in a compound of decrepit trees and flowers. The red-tiled roof leaked when it rained, and the cold days were bitterly uncomfortable. He had removed his name from the telephone book and changed his numbers. He was doing mostly low-level legal work to make a living—most clients had deserted him after his incarceration as an alleged enemy of the state a few years back—and quietly consulting human rights groups on strategies for prosecuting Moi.

To Gathenji, Kaiser’s death had the feel of a classic state-sanctioned hit, carried out by a cadre of professional assassins. It was the work of what he called “Murder, Inc.”—a vast apparatus of spies, security forces, and hit men with links to State House. Could Moi have been brazen enough to kill the American? If so, it meant anyone might be next; it suggested there might be a list the assassins were working from. His own name could plausibly be on it; many of the calls he would receive in coming days were from people concerned for his safety.

The country was two years away from the most important election in its postindependence history, a potential pivot point in East Africa’s rueful political trajectory. There was hope that Kenya’s fragmented ethnic groups might finally do what had seemed impossible before, coalescing long enough to defeat Moi’s machine. The ruler was apparently growing desperate, his grip threatened as never before.

SIX DAYS AFTER Kaiser’s death, as the priest lay in a glass-lidded brass-and-teak coffin under the vault of Nairobi’s Holy Family Basilica, Gathenji sat in the crowded cathedral among Catholic bishops, human rights activists, diplomats, and the priest’s friends and colleagues from across the country. The anger in the air was palpable. Gathenji listened as the papal nuncio—the man who’d issued Kaiser’s final summons to Nairobi—stood before the crowd, extolling the American priest’s crusade for justice and declaring him a martyr to the faith. In life, he’d been a troublemaker, an obstinate and single-minded man who’d railed against the Church’s passivity and clashed with his bishops, his missionary bosses, his fellow priests. Now it was possible to ignore the rough edges and complicated history.

The transformation had been instantaneous: The priest had been rubbed as smooth and flawless as a Masai bead, delivered from his aching body and messy humanity to abstraction, a clear and perfect symbol. After twenty-two years of Moi’s misrule, Kenyans were ready for such a symbol. The president’s face stared from every shilling in their pockets and the wall of every shop they entered—his name was on schools, streets, stadiums—and they had no trouble envisioning his hand steering the American priest to his grave. On everyone’s lips was a litany of political murders, unexplained car wrecks, implausible suicides. Outside the basilica, thousands crammed the streets in mourning and in rage. The American had already become a byword for Moi’s ruthless determination to stamp out dissent, and a rallying cry for the forces gathering against the dictator. Gathenji noticed that the regime had sent no representative to the funeral ceremony.

After the Mass, the priest’s body was loaded into a church van for transport to Kisiiland in the west, where Kaiser had spent decades, and then on to the gravesite in his last parish, in Lolgorien.

Gathenji did not follow the church caravan; there was no telling who might be waiting to ambush him on those long stretches of country road. His association with Kaiser was well known. He believed it best to lie low until facts could be gathered, the scope of the plot uncovered, the killers identified. On this score, there were grounds for hope far beyond what anyone could have expected. A team of FBI agents, summoned by the U.S. ambassador, Johnnie Carson, had crossed the Atlantic to begin investigating. Even now they were fanning out across the countryside, gathering evidence, digging up witnesses.

The ambassador had promised the Bureau’s investigation would be an independent one. To Gathenji and to others, this was a crucial reassurance, since no rational person expected the slightest help from the Kenyan police themselves; it was widely rumored that they’d played some role in the death.

Gathenji was heartened by the FBI’s reputation, by its awesome resources and name for professionalism; the agency had been instrumental in rounding up suspects in the terror bombing of the U.S. embassy in Nairobi two years earlier.

But even now, a piece of not-so-distant history supplied grounds for anxiety. A decade earlier, Moi had invited New Scotland Yard in to investigate the murder of his foreign minister, Robert Ouko, but had curtailed the probe when it pointed to members of his inner circle. The investigation had supplied the illusion of the pursuit of justice while anger abated and memories faded and witness after witness died, some of them mysteriously.

No, Gathenji thought. This investigation was in good hands. The Kaiser case would not be like Ouko’s. The Americans wouldn’t permit themselves to be Moi’s dupes, and they would raise hell if they were trifled with. So seriously was the case being treated in the United States that senators there were taking to the floor of Congress to demand justice for Kaiser.

Gathenji’s day-to-day work representing victims of political violence was dangerous enough, and the Kaiser case promised even deeper hazards. He did not think it prudent to venture too soon to the crime scene in Naivasha, a closely surveilled area with a reputation as a regime stronghold, where the slightest political talk could easily be overheard.

In the weeks that followed Kaiser’s death, he would make discreet inquiries, trying to retrace the priest’s final steps. Mostly, though, he waited. It might not be necessary for him to get involved.

The case felt coldly familiar to Gathenji in a personal way. His father, a Presbyterian evangelist, had been the victim of a politically charged slaying in September 1969, dragged from his home by fellow Kikuyus for refusing to swear an oath of tribal loyalty.

Gathenji, a twenty-year-old student at the time, believed the attack was sanctioned by elements of the Kikuyu-dominated government of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta. No one had ever been punished for his death; there had been no trial, and nothing resembling a real investigation. The experience, more than any other factor, had pushed the young Gathenji into a career in the law, which he perceived as a process—at its best—of ferreting truth from darkness and lending strength to the helpless. He had developed an abiding wariness and a deep-seated distrust of institutions, including ecclesiastical ones.

Charles Mbuthi Gathenji. For the Kenyan attorney who lost his father as a young man, Kaiser’s death had personal echoes. Photograph by Carolyn Cole. Copyright 2009, Los Angeles Times. Reprinted with permission.

Like Kaiser, Gathenji’s father had been an inveterate builder and a tough former soldier who had ignored reported warnings to adopt a more compromising stance. He had suspected that his betrayer would likely be a friend, a church mate, someone scared enough to sell him out.

Kaiser had been aware of the story of Gathenji’s father, of course. During one of their last meetings, the harried priest had invoked the lawyer’s father as a reminder of what they were both fighting for.

Both deaths had had a feeling of inevitability. Both of the dead had seen it coming, clear-eyed, from a great distance.

3

THE COLLAR AND THE GUN

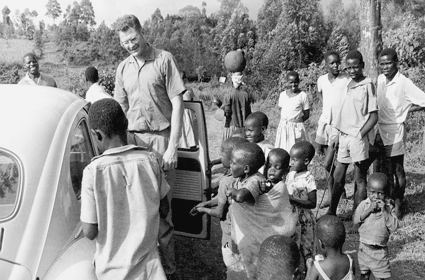

HE ARRIVED IN December 1964, stepping off a freighter into the harsh equatorial sunlight at Kenya’s eastern port of Mombasa, into a country that had just reeled exuberantly through its first year of independence from the British. Across the continent, the apparatus of European domination was being shuffled off, with varying degrees of violence, and the sense of possibility was unbounded. Kaiser was thirty-two years old and just ordained, fair-skinned and squared-jawed, a big-framed man with an army duffel bag under a thick arm. He boarded a prop plane, which carried him over the vast bulge of land toward his first parish in western Kenya. It was his first sight of the country in which he would spend most of his life—the great forests and maize farms and tea plantations, the ice-capped towers of Mount Kenya, the staggering cleft of the Great Rift Valley.

Kaiser’s early years in Kenya seem to have reflected the country’s own mood of hope and possibility. He lived in a cool, high region of softly sloping green hills dotted with huts and little granaries and covered with groves of black wattle trees, eucalyptus, and cypress, grass pastures, and terraced fields. This was the land of the Kisii, or Abagusii, a place the British had declared off-limits to European settlers.

Crowds swarmed to meet the missionary as he settled into a parish with eighteen thousand baptized Catholics and eighteen Catholic schools. Winds from Lake Victoria rustled maize rows that soared above a tall man’s head, and from the high hills of Kisiiland he could glimpse the great gulf. Families tended small farms called shambas, growing tea and coffee, as well as sweet potatoes, finger millet, and corn. Along the narrow dirt roads the women toted heavy kerosene tins of corn kernels to the power mills. Sclerotic little buses called matatus raced by helter-skelter; frequent rains stalled them in thick, impassable mud.

English and Swahili were of limited use here. The Kisii, isolated in the hills for two hundred years, were Bantu speakers whose language was grasped by few outsiders. There were no dictionaries or written grammatical rules. Kaiser set to work mastering the language, and after four months he was conversant enough to hear confessions.

The Kisii were fond of late-afternoon drinking parties, and men clustered together on stools, thrusting three-foot-long bamboo drinking tubes into pots of boiling, gruel-thick beer made of fermented millet and maize flour. The sociable Minnesota priest, invited to partake, confided to friends that he found it awful-tasting but learned how to fake a sip.

John Kaiser during his first years in Kenya, in the 1960s. He lived among the Kisii in the fertile highlands of western Kenya. A stout six foot two, he built churches across the countryside, quick, crude structures of red earth and river-bottom sand, and went up ladders with pockets stuffed with bricks. Photograph courtesy of the Kaiser family.

The huts were windowless, with walls of mud and wattle. All night during the cold months, upward through fissures in the tight grass thatching of the high-coned roofs, filigrees of smoke curled from hearth fires where families huddled, asleep on cowhides scattered across floors of dried mud and dung.

On some levels, the area was as foreign to Kaiser’s native Midwest as it is possible to conceive. Despite the presence of Catholics and Seventh-Day Adventists, most Kisii remained animists steeped in traditional practices. Polygamy was ubiquitous. For a man, the highest ambitions were abundant offspring—the only insurance of personal immortality—and multiple wives, each with her own hut, between which he would rotate. Fecundity was celebrated, the ultimate badge of a woman’s worth, and she was expected to give birth every two years while it was biologically possible. Giving birth to fifteen children was common. The Kisii birthrate, one of the world’s highest, was to Kaiser “a great sign of Divine favour.” Population control he regarded as evil. In Kisiiland, a pregnant woman did not speak of her pregnancy for fear she would appear boastful and invite malevolent envy. Any perceived advantage, in fact, invited envy and witchcraft.

“No one dies without carrying someone on his back,” went one proverb. This reflected a dark vision of invisible forces harrying people to their graves. Everything required a cause, an explanation, especially major calamities. Rancor between co-wives was a given, and a woman who found herself infertile, or who lost a child during pregnancy, inevitably suspected some machination of the women who shared her husband. The wealthy lived in fear of the poor; the poor lived in fear of the very poor; the very poor lived in fear of the wretched. It was understood that for the powerless, the jealous, and the angry, there was no recourse except through magic, and so the community’s most miserable and reviled members—childless, neglected old women, for instance—were often the most feared and vulnerable to murder. The killing of accused witches was common.

Once, Kaiser would recall, he installed a drain under an old woman’s hut, but she remonstrated with him over the shallowness of the ten-foot hole he had excavated. No, she said—they might claw down into the earth and witch me with my used bathwater: the omorogi. These were malign grave-robbing entities in human form, witchdoctors capable of casting a hex on anyone whose clothing, hair, fingernails, or excrement they could lay hold of and boil into a lethal brew.

Against those forces stood friendly diviners who could diagnose frightful omens and determine whether they were a function of witchcraft or, perhaps, of ancestor spirits angry at some slight. Other divines prescribed the proper sacrifices to banish spells, indicating whether the occasion called for the slaughtering of a black hen or a white he-goat. Kaiser viewed these divines as “clever rogues and excellent students of human psychology.” Professional witch-smellers were paid to scour one’s hut and root out the charms hidden in the roof and the walls. Having surveyed the grounds ahead of time and planted the charms, they waited for a crowd to gather, removed the alleged artifacts with a flourish—animal tails, potions, little pots—and dramatically announced that they would identify the witches responsible unless the plots were ceased immediately. Even progressive-minded Christians, lectured at church not to believe in witchcraft, secretly kept potions as a hedge against it. Some converts to Christianity abandoned it to take multiple wives, and some abandoned it in the face of serious illness or death: Confronting such calamities, you took no chances with new and unproven gods like the Nazarene.