Полная версия

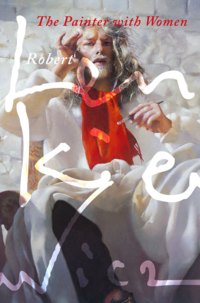

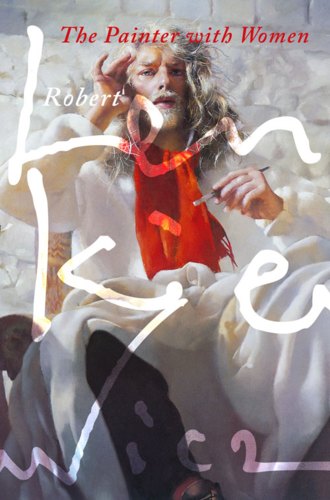

The Painter with Women

The Painter with Women

The Evolution of a Project

Robert Lenkiewicz

Copyright

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by White Lane Press

This edition published by The Friday Project in 2014

Copyright © The Lenkiewicz Foundation Trust

Front cover image: Self-Portrait as St Antony Listening. 1993.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Photographers: Mike Alsford, Dominic Burd, Bjorn Grage, Derek Harris, Anna Navas, Rhona Stokes and the late Philip Stokes. All black and white photographs, unless otherwise stated, are by Dr Philip Stokes. All colour photography is by Derek Harris unless otherwise indicated.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Ebook Edition ISBN: 9780007570096

Version: 2014-11-11

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword by Francis Mallett

The World of Robert Lenkiewicz: ‘The Bloody Chamber’ by Anna Navas

THE DOPPELGANGER 1988–1989

THE WISE MAN AND THE FOOL 1989–1990

MATHIS DER MALER 1990–1991

THE TEMPTATION OF ST ANTONY 1992

ST ANTONY’S CAVE 1993

THE PAINTER WITH WOMEN 1993–1994

Afterword: THE EARTH’S EYE 1994–1995

About the Artist

About the Publisher

Lenkiewicz at work in his Barbican studio, 1992

Foreword

A short while after I opened the New Street Gallery on Plymouth’s Barbican in 1987, Robert Lenkiewicz, with his insatiable curiosity about art and artists, became a regular visitor to the exhibitions. Since my first visit to Plymouth as a student some ten years earlier, I had been an admirer of his work, which had left a lasting, powerful impression, completely different from anything I had encountered at the time in galleries in London or abroad.

I soon asked him if he would be interested in showing some paintings, and he eventually agreed to a small showing of his aesthetic notes with nothing for sale – designed to test, I now realise, the seriousness of a commercial gallery. We hung that show together late one night, the paintings packed tightly into a tiny, blacked-out room. The nature of the explicit subject matter in a provincial city provoked a polarised response in visitors to the gallery; many fascinated, some shocked or even offended – despite a sign posted outside which warned that the local council deemed the show potentially unsuitable for those under eighteen – to which Lenkiewicz had added, ‘This is not the painter’s opinion.’ I began to visit him in his studio on a regular basis and follow the progress of his work at close quarters. Lenkiewicz became an inspiring influence. Like him, the gallery had little money: the raison d’ être was to do something interesting for itself, and survive.

Over the course of the next two years, New Street Gallery staged three exhibitions of paintings for Lenkiewicz’s Project 18 – The Painter with Women: Observations on the Theme of the Double. These were preliminary showings of the full exhibition which was finally exhibited at the International Convention Centre in Birmingham in January 1994 under the auspices of the Halcyon Gallery. These early showings were raw and basic in their presentation: cheap, cramped and claustrophobic – the complete opposite of the large-scale, slickly marketed Birmingham version.

Of all Lenkiewicz’s Projects, The Painter with Women was arguably the longest in the making, and during those six years it underwent significant development. This book charts that evolution through the artist’s own extensive diaries and other first-hand material, in particular the photographs and diaries of his friend, the photographer Dr Philip Stokes.

The Project began, almost inadvertently, as the result of events in Lenkiewicz’s private life, and as a reaction to the negative critical response to his previous Project on local education. The original theme of ‘The Double’, which harked back to earlier ideas about relationships, soon took on new dimensions with Lenkiewicz’s adoption of classical allegories, in particular, that of the monastic St Anthony of Egypt. His research into the St Anthony theme took him from Athanasius’ Life of Anthony and Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece through to more modern interpretations by French writer Gustave Flaubert and, especially, composer Paul Hindemith in his 1935 opera Mathis der Maler. As Lenkiewicz’s identification with his alter ego of Anthony grew, the sub-text of the Project increasingly became a meditation on the artist’s own life.

Two factors had a significant impact on the Project: firstly, Lenkiewicz’s decision to collaborate with a commercial gallery for the first time in presenting the full exhibition outside his own premises; secondly, the diagnosis of a serious heart condition, the treatment of which he delayed to meet the exhibition’s deadline. He later explained the consequent result as follows:

There has never been a proper showing of that Project and I feel it will make more sense when shown as a collected whole … At that time I was not very well and was also racing against time for a commercial exhibition which was held in the Birmingham International Convention Centre in 1994. It was the only time I have really compromised, but I did it because I believed that it would raise enough money to purchase these buildings in which the studio and library are housed. That’s not to say that I didn’t present the collection as I wanted under those circumstances. However, the exhibition lacked the proper context for the information. (R.O.Lenkiewicz, 1997. Mallett, F. and Penwill, M. Plymouth: White Lane Press).

As Phil Stokes had foreseen in his catalogue essay, printed independently by Lenkiewicz, the Birmingham exhibition was either ignored by national critics or incurred a kind of superior contempt – condemned, just as Lenkiewicz had ironically predicted from the outset, as further evidence of a lascivious lifestyle. This book aims to challenge that view and elucidate Lenkiewicz’s original intentions, which evolved into a daring and ambitious attempt to link his own radical theory of the physiological basis of human behaviour to the history of Western thought and religion. Even if, for various reasons, it did not entirely succeed, it was nevertheless an extraordinary and heroic achievement.

Francis Mallett, May 2011

Editor’s note: I have used the spelling St Anthony in accordance with common practice. Robert Lenkiewicz usually spelled the anchorite’s name as St Antony.

The World of Robert Lenkiewicz ‘The Bloody Chamber’

‘You must realise that I was suffering from love and I knew him as intimately as I knew my own image in a mirror. In other words, I knew him only in relation to myself.’

Angela Carter

I first walked into Robert Lenkiewicz’s studio on the Barbican in late September 1990. I had no idea what to expect. I had never heard of him and only went in because a friend and I had bumped into some other friends who had just been there. It was one of those places which immediately made you feel as if you had come to the wrong place, as though you had intruded into some private, other world. The contrast between the outside where everyday life was happening and this dark, cavernous interior made a strong impression.

There were what seemed like hundreds of paintings all piled on top of each other, from floor to ceiling, predominantly of women, or so it seemed at the time. My friend and I crept around the edges of the studio not really knowing what to look at first. I was distracted by a conversation that was happening in the centre of the room between a woman and two men. She was telling them that the painter had said he was willing to paint her but she would have to pose naked from the waist up, sitting on his lap. They were speaking in hushed, reverential tones and I remember thinking, ‘How naïve can they be – can’t they see what’s going on here?’ There was something clichéd about the whole scenario; if you were to ask anyone to describe the studio of a typical ‘bohemian’ painter, I was willing to bet that a high percentage would come up with the scene that was playing out in front of me.

Of course, a month later I was sitting on Robert’s lap, naked from the waist up, posing for him. One of the things I soon learned from Robert’s world was that things were almost never what you expected them to be.

It was, and continues to be, too easy to judge Robert’s paintings on the ‘evidence’ of his biography, and The Painter with Women Project is a particular casualty of this. When faced with a painting of Robert and a nude or semi-nude model, it is easy to see it as the slightly boastful representation of the painter with lover, so that when the Project is seen as a whole, it inevitably follows that it must be the proof of a long list of Robert’s lovers.

In the months before first visiting the Barbican studio I had been reading The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter, a collection of re-imaginings of traditional fairytales, told from a feminist perspective. The stories are violent, erotic and disturbing. Angela Carter used them to subvert the old familiar fairytale archetypes and create new and fresh meanings. One of the stories, The Erl-King, resonated very strongly with me when I walked around the studio for the first few times. According to the traditional tale, the Erl-King’s daughter was a malevolent spirit who lived in the forest preying on travellers who were lost. In Carter’s version, it is the Erl-King himself who lures women to his hut, seduces them and turns them into birds. The walls of his forest home are built from the cages of all of the birds he holds captive. One woman though understands what is at risk; she seduces him and makes a plait from his own hair with which to strangle him. A happy ending, but complicated by the fact that she listens to his stories, finds him enchanting, interesting and beautiful, but always with the knowledge that he will reduce her to something less than she is. Robert knew the traditional story and read to me the well-known version by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), put to music by Franz Schubert in 1824, but was amused by my interpretation of it as it related to his studio.

When I began sitting for Robert and spending more time at the studio, I became much more familiar with the paintings and with what Robert was trying to achieve with Project 18 (The Painter with Women). I found the whole thing troubling as I couldn’t really differentiate between the judgement I had made on my first visit and the ‘reality’ of the paintings as they appeared in increasing numbers as the months went on. It was only after quite some time and having been immersed in the work that I began to see how Robert was intentionally trying to disrupt traditional visual meanings, and the more paintings there were, the more disturbing they seemed. The vivid colours, dramatic lighting, awkward poses, strange compositions, all contributed to a hallucinatory experience which emphasised this idea of the impossibility of seeing the ‘other’ person in front of you. All you could ever hope to see was the representation or manifestation of a collection of expectations, presumptions, hopes and fears; your own fabrications reflected back at you as if by looking in a mirror. His idea was that the ‘other’ didn’t in fact exist, or at the very least they ceased to exist the minute you became involved with them. And the process of sitting for paintings merely reinforced this.

It is an odd experience to allow yourself to be observed in such a passive way by someone else; it is very far from everyday behaviour to sit for a painting in the modern world. My first sitting for Robert was awkward and uncomfortable only for the first few minutes, until he started talking and asking me about, well, about everyday nonsense really. I can remember thinking how peculiar it was that on the inside I was panicking but simultaneously behaving as though this kind of thing happened every day. What I understood was that, in a way, Robert was using me as material to explore something else; that the painting wasn’t really about me at all and as soon as I understood that I stopped worrying about it. It was equally clear that he was using himself at least as much as he was using his sitters; some of whom were friends or acquaintances, and many, of course, were lovers. But the point was always that it didn’t matter who they were as individuals, the creatures in the paintings (including Robert) were ciphers through which an altogether different set of ideas were being explored. He often said that he used himself and others as guinea pigs in an experiment to try to understand the nature of relationships, to look at the ‘falling in love scenario’ and to test his theory that all behaviour had a physiological rather than a psychological basis. His relationships with women were the laboratory for this research, and I know how cold that sounds and I know how peculiar it was but I also know how strangely honest it was. There were few real illusions about Robert’s life, only what Angela Carter would call the ‘consolatory nonsenses’ that allowed everyday interactions to occur with the least amount of discord.

What was most surprising, when The Painter with Women Project was first exhibited in Birmingham in early 1994, was that there still seemed to be a general misconception about the paintings. When seen en masse, I found it impossible to see them as titillating or sexually provocative; rather they were provocative in the truest sense. They were disturbing and discomfiting, creating a genuine sense of unease which placed them firmly outside traditional portraiture and even more firmly beyond a simple biographical interpretation. I’m not sure if the presentation of the exhibition as spectacle somehow sidestepped the bigger issues, in the same way as the drama of the studio interior on the Barbican made it impossible to engage with anything other than the spectacle of a ‘studio’. The paintings need to be seen together, in an environment which allows them space to breathe. It’s only then, I believe, that Project 18 should be judged.

Anna Navas, 2011

Detail, including self-portrait, from the diptych, The Burial of Education, the centrepiece of the 1988 Education Project.

THE DOPPELGANGER 1988–1989

On 1 April 1988, five years after he had embarked upon his seventeenth Project, Robert Lenkiewicz’s large-scale exhibition Observations on Local Education, totalling 150 paintings with over 500 sitters, finally opened in his own studio premises on Plymouth’s Barbican. By his own admission, he had found the Education Project a challenging and depressing experience, which had been reflected in many of the paintings. Aside from notable exceptions such as the virtuoso The Glue Sniffer (sometimes called Syd Sniffing Glue) and the ambitious The Deposition, the mechanical, mundane and repetitious nature of the system he was recording resulted in a substantial number of portraits which were, in Lenkiewicz’s own words, ‘literal and uninspired’. Unusually for Lenkiewicz, these were painted onto white canvas rather than his usual black, reinforcing their close tonal values – grey paintings of the grey people who were in control of the education of this country’s young.

The exhibition had been open for less than a month before Lenkiewicz was questioning the purpose of the whole Project. The opening night had been packed with friends, patrons, family and his usual circle of supporters, but since then it had met with an apathetic response. The number of people visiting the exhibition was already dwindling. The two large volumes of notes, printed at great expense, which chronicled the views of his sitters on the education system, were still piled high, attracting little interest.Neither had the heavily-researched sociological aspect of this Project, or indeed his two previous ones on Sexual Behaviour and Death, done anything to redeem his critical standing in postmodern art circles.

Less than three weeks after its opening, in his diary of 20 April, Lenkiewicz observed:

Education Project very quiet. Little local interest – and of that 90% dull and plain stupid. Must consider the sense of these Projects. So much work – so little interest – and a great deal of vacuous, dilettantish carping. After seventeen massive studies on human behaviour, I should be used to it. Feel a strong leaning towards reclusive hard work for the future only.

A couple of days later, on opening the studio, Lenkiewicz found his problems mounting when he was greeted by the ‘usual Thatcherite bills.’ With no doubt his recent first-hand experience of the cultural state of the nation still in mind, he added, ‘what a crippling abomination that woman and her ruthless philistine crew are.’

The final straw appeared to come with an article in The Times, covering the arts scene in the city to mark the four hundredth anniversary of the Spanish Armada. Lenkiewicz was classified with Beryl Cook, whose retrospective was then being staged at Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, as ‘two rather eccentric characters’, without any reference at all to his Education exhibition. In the following day’s diary (28 April), Lenkiewicz commented:

Tiresome trivialising of my work in the context of Bernard Samuels’ [Director of Plymouth Arts Centre] witterings about Plymouth’s ‘two eccentric artists’ – Beryl Cook and myself. Such a dim-witted article. Would much rather have not been mentioned than be in such silly company. No mention of Education Project – usual drivel. I get used to it. Seventeen of them now; all strangely invisible. They can never be re-staged – seems so odd that such intense activity and enquiry attracts carping trivia and nothing else.

This was immediately reinforced by Plymouth City Museum’s refusal ‘under all circumstances’ to display the Education Project poster, despite thirty seven of their staff sitting for one of the largest paintings in the exhibition. Lenkiewicz seemed to be growing resigned to it:

They are too busy with their Beryl Cooks and [Spanish] Armada bullshit to notice real labour and inquiry. After seventeen Projects I now feel almost completely invisible – and indeed it is quite pleasant really.

During the following weeks Lenkiewicz turned his interest to redesigning and reorganising his ever-expanding library with little time spent painting in the studio. At the request of a Devonport tenants’ association, he took some time out to create a large mural which featured the local residents with their MP Dr David Owen, ironically titled The Ascension into Heaven. Started on 16 May, it was officially unveiled at the beginning of August and completed shortly afterwards.

Ria as Janus. 1988. Oil on canvas, 60 × 138 cm

The original painting of Ria measured 190 × 138 cm before Lenkiewicz later cut down the canvas.

Determined to rethink his future in the light of recent experience, Lenkiewicz’s next intended Project on ‘The Family’ had been put on hold, although a few paintings from this period bear an inscription of ‘Project – Family’ on the reverse. Eventually, it was in early summer in his personal life where a new, intense passion finally began to refuel his creative energies, stimulating a return to the more private enquiries into the nature of the ‘love relationship’, which had been the prime focus of earlier Projects.

In his diary entry of 6 June, he had sensed ‘something begins’. By 23 June, he had ‘treated and sized three large canvasses black’. Before the end of the month, the first paintings in a new, as yet unspecified, series were underway with both painter and model reflected in a mirror. Two of the models, Yana Trevail and Janine Pecorini, were regular models, but his newest sitter, Benedikte Esbenson, had brought back powerful early memories of ‘her look-a-like Ria [Ney-Hoch]’, Lenkiewicz’s first adolescent love at the Hotel Shem-tov, the Hampstead home for Jewish refugees run by his parents. A painting of Ria which soon followed showed her Janus-like with two heads facing opposite directions, one uncannily like Benedikte. In Roman mythology, Janus faced simultaneously into the past and the future.

The Painter with Monca and Reuben. 1988. Oil on canvas, 157 × 161 cm

The Painter with Karen and Thaïs. 1988. Oil on canvas, 137 × 90 cm

A theme began to emerge as Lenkiewicz worked intensively on the paintings. On 5 July, his notes record:

Yana – do painting. Few painters can have done what I do in the way that I do it. Again she sat – heroically – worked very hard, made strong ‘Double’ study – the beginning of a series.

This was followed the next day with:

Janine – slowly talked her into sitting for a ‘Double study’. Worked, worked, worked so hard. Lively, sensual study.

The creative energy was returning and the ideas soon followed:

7 July – Much thought on theme of the ‘Double’ – the ‘Doppelgänger’ schlemazzle. Took from my shelves the studies by Timms/Irwin/Guerard/Rogers/Keppler/Vinge/Rank and Miller. Will re-read most of it and make sense of possibilities where the theme ‘Painter with Women’ is concerned.

In July, Lenkiewicz’s friend, the photographer Dr Philip Stokes visited Plymouth and recorded in his diary:

He [Lenkiewicz] told me too that the subject of the double, the ‘doppelgänger’, had interested him much lately, and that he was working on a small, intermediate exhibition around that theme. It would contain images largely of himself and other people, mainly women, and people would look at it as mere confirmation of their belief in his irremediable prurience. Since it is to be small as well as difficult, Robert wondered if he might hive it off into a small gallery somewhere, probably in New Street; thus avoiding unnecessary interruptions to the ‘Family’ Project.

The first paintings in the ‘Double’ series in Lenkiewicz’ studio in 1988 show (left to right): The Painter with … Janine Pecorini, Karen and Thaïs, Patti Avery.