Полная версия

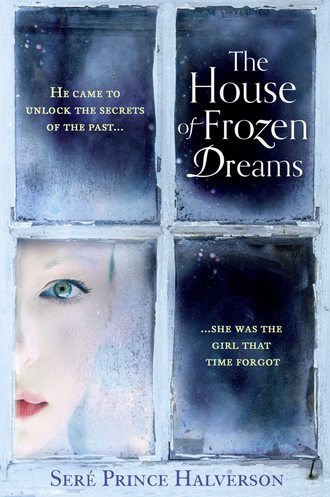

The House of Frozen Dreams

His cellphone was useless; no service. He should turn back. Get in the car and head into town and return tomorrow. But his dad, his mom, Denny—they seemed so close: a slap on his back, an arm around his shoulders, as certain as the cold on his feet, and he shivered from both. He smelled the fire from their woodstove, as if they kept it burning all these years. All around him they said his name in all its variations and tones, so achingly clear: “Kache, honey?” “Oh, Kaa-achemak, there’s my Widdle Brodder …” “Did you hear me, Son? Pay attention.” He heard their snow machines, though there wasn’t any snow, though there wasn’t any them. He didn’t believe in heaven, exactly, but this place was thick with recollections and maybe something more. If their spirits watched him, somehow, from somewhere, didn’t he want to prove he had become capable of more than any of them thought possible? But had he? No. A city boy number-cruncher-turned-couch-potato who wore pretty boots and forgot a decent flashlight would hardly invoke awe. Still. If they were waiting, they’d been waiting twenty years and he didn’t want to make them wait another day.

He made his way through the mud, tripping, sinking, until the full moon rose from behind the mountains. Like a helpful neighbor in the nick of time, it shined its generous gold light through the cobalt sky. A wolf howled, holding a single lonely note in the distance. The scent of spruce and mud and sea kept dredging up the imagined hint of smoke. All those scents had always come together here. Even in the summers, a fire burned in the woodstove.

Now Kache spotted the downed trees clearly without the flashlight, and he walked as quickly as his mud-soaked city boy boots would allow—until the last bend, where he stopped and readied himself for what lay ahead.

It was then, as he stood on the road that was no longer a road, breathing deep, heart hammering, that the realization jarred him. The familiar scent. The spruce, the soaked loamy earth, the sea; yes, yes, yes. But wood smoke? It was too strong, too distinct now, not merely his imagination. It was definitely the smell of wood burning, and coal too.

He edged around the last corner, saw the house through the boughs of spruce and naked birch and cottonwoods. It stood, not a dejected pile of logs, but tall and proud, glowing with warm light.

What?

Who?

Smoke rose straight up from the chimney, as if the house raised its hand. As if the house knew the answer.

SEVEN

Kache stood, staring, the cold mud oozing into his boots and now through his socks. The house stared back as it always had in his mind, glowing with light and life in the middle of the cleared ten acres.

Who in the hell?

Sweating, watching, allowing for the strangest glimmer of hope. Maybe he really had been dreaming, really had been sleeping, and now that he’d finally awoken, life might resume as it had before? Maybe all and everyone had not been lost? Maybe only he had been lost.

In these last two minutes he felt more alive than he had in two decades. Maybe he’d been under some sort of spell, broken at last on this anniversary. His mom would love the mysticism and synchronicity of that.

He shook his head, boxed his own ears. What he needed was common sense. His dad would have reamed him for not grabbing Aunt Snag’s .22 that hung on the enclosed back porch. As much as Kache hated guns, never got himself to actually shoot one, he knew it was crazy to approach the house without carrying one, especially given the lights and smoke. His dad used to say it didn’t matter if you were far to the left of liberal, if you walked by yourself in the boondocks of Alaska, you should carry a gun.

His feet started moving forward anyway. Forward to his old house, his old room. Who in the hell?

Inside, a dog barked. A shadow passed by one of the windows. The shade went down, snapped up again, quick as a wink, then shut. The other shade went down. The soft light behind them off now, replaced with the dark he’d expected to find in the first place.

He pressed his back against the old storage barn, took deep breaths and tried to line up his thoughts, which kept ricocheting off each other. He should go back, return in daylight with the gun. Call Clemsky, Jack O’Connell, a few of the others. He licked his palm and made a small circle on the mud-covered window beside him. He peered in. It was dark, and he barely made out the outline of his dad’s Ford pickup. Aunt Snag had even left that, probably driven it home that day from where his dad had parked it by the runway. She should have used it. That would have meant something.

The dog was going nuts now, continuously barking. Kache pushed on the storage barn side door; it wasn’t locked, opened easily. Along the wall he felt for the shovel, the hoe, the rake. He decided on the sharp, stiff-bladed rake. Better than nothing.

Hovering behind a warped barrel, then a salmonberry bush, he tried the back door of the house, knowing it would be locked. He crept along to the first kitchen window, remembering. That window never did lock. He slid it open, pulled himself up on one knee, lowered the rake in first, then jumped down inside with a thud.

The barking stopped, became a whine and growl. He pictured a hand muzzled around the dog’s nose. Kache tried to make himself smaller by crouching, then slipping along the wall. The thought came to him: I am not the intruder here. This is my house. He’d forgotten, taken on the attitude of a thief instead of a protector, and now he stood straight with his rake, as if that would shift the perspective of whoever was upstairs, as if the moment was a black-ink silhouette that changed depending on how you looked at it.

The whining, the growling. Kache could smell his own nerves, so of course the dog could. He ran his hand along the blue-tiled kitchen counter, up to the light switch, flicked on the lights. Nothing had changed. As always the woodstove warmed the large living room, which had once held four rooms before his mom and dad remodeled. The same furniture stood in its assigned places. His mother’s paintings still hung heavily on the thick, chinked walls. Photos of the four of them, baby pictures, wedding pictures, Christmas pictures all lined the top of the piano. He ran his finger along the top; free of dust. Games and books crammed the shelves. Kache fingered the masking tape his mother had sealed along the broken seam of the Scrabble box. He fought urges to throw the rake, to vomit, to leave.

Upstairs, another growl. Kache choked out, “Hello?” He listened. Nothing. “Hello?”

Then, rage. He pounded up the stairs. “Answer me! Answer me!” He flung open doors and flipped on lights to bedrooms that stood like shrines to the dead. All as they’d left it. In his room, a yellowed poster of Double Trouble was still stapled to the wall, Stevie Ray Vaughan still alive and well. As if neither his plane nor Kache’s family’s plane had ever gone down. As if Kache still slept in the bottom bunk and dreamed of playing the guitar on stage.

Under the bed, the dog let out barks like automatic ammunition, scrambling his claws on the wood floor. Kache held out the rake. “Who’s there!” An arm shot out, fist clenched around the handle of Denny’s hunting knife. But even more startling than the knife: the arm, clad in the sleeve of his mother’s suede paisley shirt. The shirt Kache and Denny bought in Anchorage for her birthday, and that she referred to as the most stylish, most perfect-fitting shirt on the planet that had somehow forged its way to the backwoods of Alaska. “Mom?” Kache whispered under the barking dog. “Mom?” he said louder, his eyes filling.

The dog poked his nose out, then was yanked back by the collar. A husky mix. Kache bent down, trying to see through the thick darkness. “Mom? That’s not you?”

The knife retreated and the hand reappeared, unfolded. Not his mother’s hand. It spread, splayed and pressed its fingers on the floor, until a blonde head emerged, and then a face looked up. Not his mother’s face. That was all he saw. It was not his mother’s face, and a new grief slammed him to his knees.

Mom.

Minutes went by before he realized the dog was still barking and this other face that was not his mother’s looked up at him for some kind of mercy, and though he hated the face for not belonging to his dead mother, he saw then, that it was a woman’s face, that it was round, that blue eyes begged him, that lips moved, saying words.

“Kachemak? It is you? You are not dead?”

EIGHT

There had only been one visitor, years before.

Kachemak had caught her so completely unprepared that her heartbeat seemed to be running away, down to the beach, while the rest of her waited.

He looked older, his face more angled than in the photographs. But he still had the same curly hair, though shorter now, and the same heavy brows. His height—taller than the rest of the family in every photo—also gave him away. He asked her to call the dog off, and so she did, and pulled herself out from under the bed though her arms wobbled like a moon jellyfish. She shoved her trembling hands in her pockets and tried to appear brave and confident.

And yet she felt grateful it was him. She knew that Kache, as the family called him, was a gentle soul. But she also knew it was possible for a man to appear kind and yet be brutal. She fluctuated between this wariness and wanting to reach out and hold him as a mother would a child—even though he was older by ten years.

All this time she’d pictured him a boy like Niko, not a man like Vladimir. And all this time she’d thought him dead. She’d figured it out on her own, but then Lettie had confirmed. “You may as well be here. They’re all gone,” she’d said and snapped her fingers. “And Lord knows they’re never coming back.”

When Nadia asked, “Was it the hunting trip?” because she’d seen a reference to it on the calendar and elsewhere, Lettie nodded and held a finger to her lips while a single tear ran down her worn cheek and Nadia never asked her about it again. They’d had an unspoken mutual agreement not to pry, to leave certain subjects alone.

But now Kache stood before her, older, a grown man who had called her “Mom.” Was Elizabeth alive too?

“Who are you?” he asked. She shook her head. She should have not spoken earlier, should have pretended she did not understand English. But already she’d given herself away. “Look—do you know me?” he said. “You called me by name. You thought I was dead? Do I know you?”

She shook her head again, walked back and forth across the small room, touching chair, lamp, bed as she went. Moving like this, she could turn her head and glimpse him sideways without feeling so exposed face to face. The years had marked him, but he still had a youthful expression, those big dark eyes. Though Lettie had stayed clear of certain topics, Nadia knew so much about the boy: a gifted musician, an awkward teenager who felt out of place on the homestead, who fought bitterly with his father and had been a constant disappointment to him, but whose mother understood him and felt sure he would find his way. Nadia knew when he lost his first tooth (six-and-a-half years old), when he said his first word—moo-moo for moose—(ten months old). How he cried when his mother read him Charlotte’s Web.

“Can you stop pacing?”

She stopped. They stood in the lamplight, he staring at her, she staring down at her slippers. His mother’s slippers. He didn’t know anything—not one thing—about her, not even her name. All these years and years and years nameless, unknown. Only Lettie knew her, and Lettie must be dead. Nadia was afraid to ask.

“What’s your name?” Kache said. “Let’s start with that.”

Leo let out a long sigh and rested his head on his paws, sensing no more danger. How could a dog get used to having another human around so quickly?

Squaring her shoulders, taking a deep breath, she said her name. “Nadia.” She wanted to shake him and call out, I AM NADIA! but she kept quiet, still, erect.

He held out a large hand. “I’m Kache.”

She kept her hands in her pockets and her eyes to the ground, even though part of her still wanted to hug him, to comfort him. She practiced the words in her head, moved her lips, then put her voice to it without looking up: “Your mother is alive?”

“No. She died a long time ago.”

At once the new hope vanished. “Then why do you ask this, if I was your mother?”

“My brother and I gave her that shirt.” She felt her face flush. “I lost my head for a minute. You scared the hell out of me. And I still have no idea who you are.” She looked up to see him cross his arms and take an authoritative stance, then she turned her eyes back to the floor.

It was her turn now to speak. This, a conversation. She was conversing with the boy she thought had died, whose bed she slept in, whose jeans she wore, always belted and rolled up at the cuffs. She had talked to herself, to Leo, to the chickens and the goats and the gulls and the sandhill cranes, to the feral cats, to any alive being, driven by the fear that she might forget how to talk. She hadn’t spoken to another human except for Lettie, four years ago. But here she was, speaking with someone, in English, no less, which is what felt natural to her now after reading nothing but English all this time.

“Nadia.” He nodded as he said it, as if he liked the name.

Her name. It twisted through her, and she hung her head as tears leaked down her cheeks. Soon a sob escaped, and then another. She did not cry often. What was the point? But here she was, crying for every day she hadn’t.

“What’s wrong? I won’t hurt you, don’t cry …” but she could not stop. She had been so alone, so utterly alone for too many years, more than were possible and now, all changed. Here was someone she knew, someone who now knew her name, knew she was alive, someone who might help her or might turn on her. He touched her arm and she jumped. He stepped back and said again, “It’s okay, I won’t hurt you.”

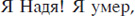

Through the stuttering gasps, more words erupted, but they came in Russian, too loud, almost screams:

NINE

Snag lay in bed, waiting to hear the gravel popping under her truck’s tires, trying not to worry but worrying anyway. Maybe Kache wouldn’t come back. Maybe he’d just drive straight to the airport and take the next flight out. She hoped not. It was so good to have him home, even though he’d brought all their ghosts with him, and now those ghosts plunked down in her room, shaking their heads at her, whispering about how disappointed they were that she hadn’t once gone back to the homestead, at least for the photo albums.

She did have the one photo. Opening the drawer to her rickety nightstand, she pushed aside the Jafra peppermint foot balm. She told her customers how she kept it in that drawer. “Just rub some on every night and those calluses will feel smooth as a baby’s butt.” She never actually said she rubbed the stuff on herself. No one had ever felt the bottoms of her feet, and she reckoned no one ever would. Under the still-sealed Jafra foot balm was an old schedule of the tides, and under that lay a photograph wrapped in tissue with faded pink roses. This was what she was after. She carefully unwrapped it and switched on the lamp, though she almost saw the image well enough in the moonlight.

Bets at the river: tall and slender, wearing those slim, cropped pants Audrey Hepburn wore, a sleeveless white cotton blouse and white Keds. Her hair swept back from her face in a black crown of soft curls. She had red lips and pierced ears, which until then Snag had thought of as slightly scandalous but on Bets looked pretty; she wore the silver drop earrings her Mexican grandmother had given her that matched the silver bangles on her delicate wrist.

Snag remembered handing her the Avon Skin So Soft spray everyone used because mosquitoes hated it. Snag had broken some company record selling bottles of the stuff to tourists. Bets sprayed it on her arms and rubbed it in. Her skin glistened and looked oh so soft.

Bets didn’t look like anyone Snag had ever come across in Caboose, or even Anchorage. Half Swedish and half Mexican, and from Snag’s perspective, the best halves of both nations had collided in Bets Jorgenson. She’d grown tired of her job as an editor in New York City, jumped on a train, then a ferry, and come to visit her Aunt Pat and Uncle Karl, who at the time lived in Caboose. Pat and Karl had asked Snag to take their niece fishing along the river.

That day Bets, clearly mesmerized, seemed content to watch Snag, so Snag was showing off something fierce. Everyone agreed: Snag was one of the best fly fishermen on the peninsula.

Bets sighed, dropped her chin onto her fists and said, “It’s like watching the ballet. Only better.” She drew a long cigarette out of a red leather case, lit it with a matching red lighter, and said she’d never seen a girl—or a boy, for that matter—make a fly dance like that. “It seems the fish have forgotten their hunger and are rising just to join in on the dancing.” She studied Snag late into the day, kept studying her, even after Snag fastened her favorite fly back onto her vest, flipped the last Dolly Varden into the pail, then pulled the camera from her backpack and took the very picture of Bets she now held in her hand. Bets sat on a big rock, legs crossed at the ankles, pushing her dark sunglasses back on her head, biggest, clearest smile Snag had ever seen. That picture had been taken a week and two days before Glenn returned home from Fairbanks and fell elbows over asshole in love with Bets too.

TEN

The woman threw back her head and screamed in a foreign language, then, dragging the dog, ran into the bathroom. She locked the door. Kache pressed his ear against it and asked her to come out but she didn’t answer.

Downstairs on the hall tree hung his old green down parka with the Mt Alyeska ski badge his mother had sewn on the collar. He yanked it on over his lighter jacket.

Outside. Fresh air. Breathe. The moonlight now reflected in a wide lane across the glassy bay, like some yellow brick road beckoning him to follow it. Instead he headed through the stale snow and fresh mud of the meadow toward the trail. He walked fast, puffs of steam marking his breaths like the puffs that sometimes rose from the volcanoes down across Cook Inlet.

He could erupt any moment.

He could do his own screaming.

Who the hell do you think you are? This is MY house. MY clothes. MY mother’s shirt.

How long had she been here, eating, bathing, sleeping, breathing in his memories? And who else? How many others had made his home their own?

At the biggest bend the trail opened to the left, and there, five paces away, the plunge of the canyon. He didn’t go another step. He shivered—partly from the cold, partly from childhood fears.

In the quiet, a hawk owl called its ki ki ki and the canyon answered Kache’s ranting with questions of its own.

YOUR home?

Have you given a rat’s ass about one inch of this land or one log of that house?

Has it occurred to you? That strange woman may be the only reason YOUR home is still standing?

Kache shook his head hard enough to shake his thoughts loose. The canyon obviously didn’t speak to him like that. To prove it, he did what they’d all done a thousand times, whenever they’d arrived at that spot on the trail:

Across the dark, vast crevice he yelled, “HELLO?”

And the canyon answered as it always had, “Hello …? Hello …? Hello …?”

ELEVEN

The front door closing, his footsteps clunk clunking down the porch stairs. She peeled back the curtain to see him cross the meadow. Where was he going? She turned on the bathroom light and stared at her reflection in the medicine cabinet. Her hair was disheveled from climbing under the bed, so she pulled out the elastic band and brushed. Leo lay down at her feet.

Nadia touched her fingertips to her lips. “Hello,” she said to the mirror. Her voice shook. All of her shook. Her throat seared from the screaming. But she did not scream now. She imagined her reflection was Kachemak and she kept her eyes from looking away. It was one thing to talk to plants and animals and quite another thing to have a conversation with a human—with a man.

“I am frightened.” No. “I am fine. Fine. I go now.”

She raised her chin, put her hand to her hair.

“Thank you for letting me stay.”

Her eyes narrowed. “Stay away from me or I kill you.” She placed her fists on her hips. “Son of bitch. Damn you to hell, son of bitch.”

But Kachemak’s mother was Elizabeth. Kind, smart Elizabeth. And this was her Kache. “I apologize. Your mother is not bitch. Your mother is very good. Your grandmother is very good.” She touched her throat. “Kache? Please? You are still good person also?”

TWELVE

The sun pulled itself up over the mountains to the east, casting salmon-tinged light on the range and all across the bay, even reaching through the large living-room windows. Kache sat sipping dandelion root tea with the woman Nadia, she in his mother’s red-and-white-checked chair, he on the old futon. Neither had slept. Only the fire crackling in the woodstove broke the silence between them. She burned coal and wood, which filled the tarnished and dented copper bins next to the stove. She must have collected the coal on the beach the way his family had done. It smelled like home.

The fire popped and they both jumped. “Bozhe moi!” Her hand went to her mouth, her eyes still downward. “Sorry.”

Wait—that language, her accent—Russian?

An Old Believer?

In junior high Kache wrote a Social Studies report on the Old Believer villages. The religious sect had descended from a band of immigrants who’d broken off from the Russian Orthodox church during the Great Schism of the seventeenth century, and later, during the revolution, fled Russian persecution, immigrated to China, then Brazil, then Oregon, before this particular group feared society encroaching, influencing their children. They moved to the Kenai Peninsula in the early nineteen-sixties, beyond the end of the railroad line, past Caboose, then still called Herring Town, and staked their claim to hundreds of acres beyond the Winkels’ own vast acreage.

At first everyone pitied the Old Believers. A child died in a fire and a woman was badly scarred trying to save her daughter. “They’ll never make it through another winter,” locals predicted about the small group of long-bearded men and scarf-headed women. But then a baby girl was born, and the Believers saw the tiny new life as an encouragement from God. In the spring they began to fish and cut timber. They built wood houses, painted them bright colors—blue and green and orange, and more Believers came from Oregon. They built a domed church. Eventually they too divided over religious differences and the strictest of the group ventured deeper into the woods. But both groups lived separated from the rest of the world, exempt from laws other than their own rituals, unchanged since the seventeenth century, which they believed were from God. Back in the Seventies, Kache’s dad said they ignored a lot of the fishing laws, and when the fishermen had a slow year, they often blamed the Old Believers.