Полная версия

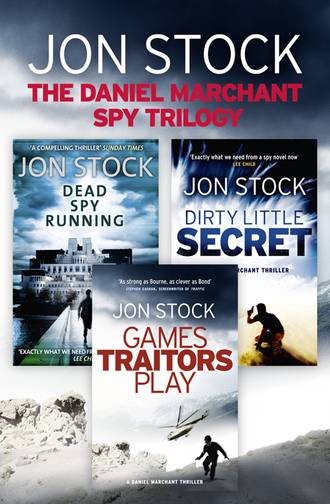

The Daniel Marchant Spy Trilogy: Dead Spy Running, Games Traitors Play, Dirty Little Secret

‘Stay here for an extra day,’ she said quietly, holding him tightly. ‘I’d like that.’

‘What about my ticket?’ he said, slowly unpicking the mother-of-pearl buttons of her shirt. Leila was stepping out of the shower now, hair wrapped in a turban of towel.

‘What about it? I’ve got a friend, she runs a small travel agency not far from here. We send all our guests there. She can change it, she knows everyone up at the airport.’

But David Marlowe didn’t give a damn any more about his ticket, or Daniel Marchant, or Leila, as he eased Monika out of her shirt.

18

Sir David Chadwick had spent a lifetime brokering compromises in Whitehall meeting rooms, but even he was struggling to keep Marcus Fielding and Harriet Armstrong apart.

‘Before this gets referred to the PM, as it will, I need to know exactly what you’re alleging here, Harriet,’ he said, looking across his oak-panelled office at Armstrong, who was on the edge of her seat.

‘The Poles must have been tipped off by someone,’ Armstrong said, glancing at Fielding. He was sitting at a safe distance, equally upright though less on edge. On his lap was a clipboard, covered in a patchwork of blue and yellow Post-it notes. Armstrong had often wondered what Fielding wrote on them. No reminders to bring home dinner for his wife, because he had never had one, a fact that still intrigued her.

‘Marcus?’ Chadwick asked.

‘I think we’re underestimating our friends in Warsaw. The new government’s been looking for a way out of these renditions for some time now. I imagine someone was keeping the airbase under surveillance and decided that they no longer wanted a corner of their country run by America.’

‘Marcus, you rang me about the flight,’ Harriet said. Fielding’s poise riled her. Everything about him riled her: his equanimity, the Oxbridge intellect, those safari suits. And how could someone be ‘celibate’, as he had apparently defined his sexuality to the vetters, explaining that he was simply not interested in sex of any kind, with anyone? Her ex-husband had once accused her of something similar, but she hadn’t consciously chosen to deny him; it had just gone with the long hours.

‘True?’ asked Chadwick.

‘As you both know, we monitor all flights in and out of the UK, particularly ones that file dummy flight plans. To avoid confusion, I suggest that the next time the PM decides to authorise an undeclared CIA flight through British airspace, someone has the courtesy to tell us.’

‘Harriet?’ asked Chadwick, turning back towards her like a centre-court umpire.

‘It was agreed that the Americans could talk to Marchant,’ she said.

‘Talk to him, not try to drown him,’ Fielding replied. ‘And I think we said it should be in this country.’

Fielding’s last comment was addressed to Chadwick, who didn’t care for the look that accompanied it. ‘Oh, come on, Marcus,’ Chadwick said, a nervous smile creasing his pale jowls. ‘It must have felt like home from home, given the number of Poles over here.’

Harriet returned the smile, but Fielding stared out of the window onto Whitehall, watching an empty 24 bus make its way up towards Trafalgar Square. He didn’t have time for cheap jokes about immigrants. He didn’t have time for Chadwick, sitting behind his oversized desk like a child who had broken into the headmaster’s office.

‘So where is he now?’ Fielding asked him.

‘I was rather hoping you’d tell us.’

‘I want my man back alive. That was the other part of our deal.’

‘If you haven’t got Marchant, then who has?’ Chadwick turned back to Armstrong.

‘Spiro flew out to Warsaw this afternoon. They think he’s still in Poland.’

‘He lost him, he can bring him back,’ Fielding said, rising from his seat. ‘I’ve asked Warsaw station to keep a lookout.’

‘Prentice,’ Armstrong said coldly.

‘You know him?’ Fielding was now at the door, clipboard under one arm.

‘Only by reputation.’

‘Quite. One of the best in the business.’

‘And once Marchant’s found?’ Chadwick asked, standing too, sensing another altercation.

‘Then it’s our turn to ask him about Dhar,’ Armstrong replied.

Fielding opened the door to leave.

‘Just make sure we don’t lose him again,’ said Chadwick. ‘Twice would be careless. Thank you, Marcus.’

Fielding closed the door behind him, leaving Armstrong and Chadwick alone.

‘Whatever the differences between you two, I don’t want it affecting operations on my watch, Harriet.’ Chadwick had remained standing.

‘Spiro’s livid.’

‘I’m sure he is. But it should surprise no one that the Service looks after its own. It always has done. Is this Hugo Prentice protecting him?’

‘Quite possibly. We could throw the book at Prentice if we want. He’s had run-ins with Spiro before. He’s had run-ins with everyone. Any other agency would have got rid of him years ago.’

‘I’ll talk to Spiro.’ Chadwick paused, shuffling papers needlessly on his desk. ‘We want this contained, Harriet. The Americans need Marchant back.’

Fielding found Ian Denton, folder in hand, waiting for him in the room outside his office, making quiet conversation with his secretaries. The Chief of MI6 was entitled to three of them: his personal assistant, a letters secretary and a diary secretary. Anne Norman had been PA to the previous four Chiefs, all of whom had valued her brusque phone manner, particularly when taking awkward calls from Whitehall. She had resigned over the Stephen Marchant affair, only to be talked into staying on over a long lunch at Bentley’s with Fielding. A formidable spinster in her late fifties, she was the archetypal bluestocking, except that she always wore bright red tights, usually with red shoes. Fielding had often meant to ask her why, but he was in no mood for small-talk after his meeting with Armstrong and Chadwick.

‘Come,’ he said, walking through to his office. Denton followed, closing the door behind them. ‘What have you got?’

‘Marchant’s with AW,’ Denton said, quieter than ever.

‘And the Americans?’

‘Spiro’s turning Warsaw upside down. Prentice says they won’t find him.’

Fielding hesitated a moment. ‘What about Salim Dhar? Any progress?’

Denton pulled out a sheaf of papers from the folder he was holding. He, like Fielding, lived an ordered life, and he had grouped the sheets into clear plastic files. He handed the top file over to Fielding with the confidence of someone who knew he had done well. It was a printout of an old bank statement.

‘Dhar’s father, his current account in Delhi,’ Denton said. ‘This deposit here was his monthly salary payment from the US Embassy.’

‘And this one?’ Fielding asked, pointing to another payment that had been circled with red biro.

‘As far as his Delhi branch manager is concerned, it was a regular payment from relatives in South India. Paid in rupees from the State Bank of Travancore, Kottayam. Works out at about £100 a month in today’s terms.’

‘Not bad for an administrative officer. You’d expect someone with a job in Delhi to be sending money back to his family in the south, not receiving it. So who was paying him?’

Denton paused for a moment, knowing that he would be blamed in some indirect way for what he was about to say. ‘We’ve followed the financial trail back further.’

‘And?’ Fielding glanced up at him irritably.

‘Cayman Islands, one of the Service’s old offshore accounts.’

‘Christ.’ Fielding tossed the file onto his desk.

‘Set up by Stephen Marchant in 1980.’ Denton pulled out another file, made up of sheets more faded than the first, and handed it to Fielding, hoping that it would become the new focus for his anger. ‘We found this in the FO’s employment files. Seems like the first payment was put through shortly after Dhar’s father was sacked from the British High Commission. There was a small disciplinary hearing, at which various references were read out, including this one from Marchant. He felt very strongly about it, thought the man had been shabbily treated.’

‘So strongly he set him up with an index-linked agent’s pension.’ Fielding pushed his chair back towards the big bay windows that looked across the Thames towards Tate Britain. Denton was still standing. ‘It doesn’t add up. A junior member of the commission’s admin staff–perfectly decent man, I’m sure, but not exactly a high-value intelligence asset. Is there any record of him providing information to the Service?’

‘Nothing so far. For what it’s worth, the monthly payment was roughly equal to the difference between his British salary and his new, lower income from the US Embassy.’

‘Very fair. Except that Marchant didn’t have the authority to set up something like this. Even back then.’

‘It never caught the eye of our auditors.’

‘He always did know how to handle the bean counters. Are the payments still being made?’

‘No. They stopped. 2001.’

‘Why then?’

Denton shook his head. ‘We don’t know yet. But there’s one other thing. We’ve found a second payment Marchant requested after he’d left India. To his driver, one Ramachandran Nair. Same account, gave him a pension of £50 a month.’

‘And we’re still paying him?’

‘Seems so, yes.’

‘Dear God, no wonder we’re always over budget. Do whatever you have to, Ian. I need to know why Marchant was paying Dhar’s father. What was it he did for him?’

19

Hassan was the only asset Leila had ever slept with. It wasn’t usually her style, but at least he was young and good-looking. Most agents were paid, but Hassan had always been an exception, ever since he’d provided her with enough information to thwart an attack on a passenger plane over Heathrow. After that he could name his price, which in his case was hard sex rather than hard cash.

According to Fielding, fragments of intelligence in the wind pointed to some sort of Gulf connection to the attempted attack on the marathon. Word had gone out for all assets, however tenuous, to be harvested for HUMINT. Hassan knew more about what was happening in the Gulf than any Western analyst in Whitehall, drawing on his Wahabi roots to keep informed of the region’s complex terror network. Ostensibly he was a travel journalist, writing for one of the many English-language newspapers in Qatar, but he didn’t need the salary. His family was worth more than MI6’s annual budget, which was why he was asking Leila if she could leave the media awards dinner early and host her first home match.

‘You’ve always played away,’ he said, topping up her glass of fizzy water. The dinner, in the ballroom of the London Hilton, was dry, which was why a herd of Western journalists was migrating steadily to the hotel’s bars. It was a dry affair in other ways, too. There was little cross-cultural mingling, despite the evening’s theme of global unity and despite the best efforts of the MC, a risqué, half-Iranian, half-British female comedian (‘Whenever I tell people my biological clock is ticking, everyone ducks’).

Leila had wanted to find her, say how much she had enjoyed her act, but Leila was acting too. She was attending the evening in the guise of a Gulf-based travel PR, one of her regular operational covers. It was the first time she had used it on British soil, and she felt more nervous than usual.

‘I’ve booked a room here,’ Leila said, wrestling with a sudden urge to join the hacks at the bar. She was used to having sober sex with Hassan, but tonight she felt the need for a drink.

‘Leila, that’s very thoughtful, but do you know what? The Hilton bores me. Hotels bore me. I spend all my life in hotels. Let’s go back to your place. Why not? It’s your first time on home soil.’

Hassan was proposing that she step over a line she had never crossed before. Apart from the security implications of taking an asset back to her home, there were personal issues too. Sex in a hotel room was one thing, but at home, the place where she retreated from Legoland, the sanctuary she returned to after postings abroad? That was different.

‘I’m sorry, Hassan. I’ve paid for the room. And it’s a long way back to where I live.’ But she knew, as soon as she spoke, that she had said the wrong thing.

‘You’ve paid for a room?’ he laughed. ‘So what? I’ll pay.’

She looked away at the myriad of tables, each with its candles and extravagant flower display, spread out across the ballroom floor like an illuminated orchard. She hated not being in control.

‘It’ll be worth it,’ he said, leaning forward to touch her arm. ‘I know who supplied the isotonics.’

Earlier that day, after her final debrief at Thames House, Leila had returned to her desk at Legoland for the first time since the marathon. The building was still buzzing with the attempted attack. In the canteen she noticed the glances, overheard people talking about her with an obviousness unbecoming of spies. The Gulf Controllerate, where she worked, was like a City traders’ pit. There were no flickering international share prices, but the hum of ringing phones and the vast data-analysis charts on the walls, linking hundreds of names across the world, conveyed a similar chaotic urgency. Her line manager said it was even busier than in the days immediately after 9/11.

It had been a relief when Marcus Fielding had called Leila in to his office and asked about Marchant, how she had found him the day before. He had also praised her for the way she had thrown herself back into work, and repeated the need for her to be patient. Marchant, he said, was to be questioned by the Americans, which wasn’t ideal, but he had every confidence he would be back in the fold soon. It was best, though, if he and she didn’t see each other for a few days.

Leila didn’t pursue what he meant by ‘questioned’, for fear of betraying Paul Myers, but there was also something about Fielding’s manner that discouraged further discussion of Marchant. Instead, he wanted her to focus on Hassan, and to find out whatever he knew about the marathon attack. His intelligence had been accurate in the past.

‘Squeeze the pips,’ Fielding had said, in a way that made her doubt his reportedly celibate status. They both knew that she had never filled in a request form for Hassan to be paid, and the matter had never been discussed. Leila thought about that now as she tied Hassan’s hands to the posters of her brass bed. It had shocked her how quickly she had got used to sleeping with a man she didn’t love, and struggled to fancy. She had told Marchant after the first time, but he didn’t want to know. It was her job: they would both have to sleep with other people occasionally, so they should just get on with it. The only reason for them to confide in each other, he said, would be if it meant anything more than sex.

Leila didn’t find it so simple, and was annoyed that Marchant could be so matter-of-fact. She remembered when, towards the end of their six months at the Fort, a female instructor had taken her and the three other women in that year’s intake for a drink one night, to pass on a few personal tips. She expected them all to deal with the health risks themselves. Her advice was solely about the emotional damage that professional sexual liaisons could result in. The key, she had said, was to think of themselves as actors playing out a scene in a film.

Leila tried to imagine the camera crew now, as she looked around her dimly lit flat. Hassan had hinted at less orthodox sex on their last meeting, in Doha, but she had kept their encounter firmly on the straight and narrow. Tonight would be different, something to trouble the censors.

‘Leila, this is wonderful,’ he said, lying face-up on the sheets. He was naked, his wrists and ankles tied securely with scarves to all four bedposts.

‘It’s what they call home advantage,’ she said, picking up two large lit candles she’d been given by Marchant. She walked over to the bed with them. They were both brimming with beeswax, which burned hotter than ordinary candle wax. Still in her underwear, she placed them carefully by the bedside, then went over to her CD player and turned up Natacha Atlas. Outside, the lights of Canary Wharf Tower burned brightly as bankers worked late into the night. For a moment, she longed for a normal job. She drew the souk-bought curtains, sent by her mother, took another scarf from a drawer, and tied it over Hassan’s eyes. He sighed with approval, mouthing a kiss at her. ‘Darling Leila,’ he whispered, but she put her finger to his lips.

‘Ssshh,’ she said, passing him the mouthpiece of the ghalyun, an Iranian hookah that she kept in the flat. Her father had brought it back from Tehran in 1979. As Hassan drew heavily on the mix of tobacco and hashish, she moved up onto the bed, straddling his chest, her back to him. Somehow it was more bearable if she couldn’t see his face. Taking him in one hand, she reached across with the other to the candles on the bedside table.

‘Are you ready?’ she said quietly, working him firmly. She turned and removed the hookah pipe from his mouth.

‘I’ve never been more ready in my life,’ he said.

Hassan, Leila suspected, was a coward at heart, despite the bravado. Too much pain and he would cry for his mother. ‘How brave are you feeling?’ she asked, holding a candle six inches above him, then lowering it to three so the beeswax had less time to cool.

He screamed, as she knew he would, writhing for a few seconds as the near-boiling wax dripped onto his sensitive skin. But his smile returned as the wax hardened. Hassan, she realised, was weirder than she had thought. She caught the smell of his sweet cologne as she dripped more boiling wax onto him. Suddenly his presence in her home was overwhelming. She resented him, her job, the compromising position she found herself in; but then she thought of what they were doing to Marchant, wherever he was, and moved the candle even lower.

Half an hour later, Leila was running out of tricks, and Hassan still hadn’t told her anything. Earlier, in the taxi from Park Lane to Docklands, he had insisted that his information was so potentially compromising, for him and for his country, that he would need something special to round off their home fixture. Only then would he talk.

She placed the hookah back in Hassan’s mouth and told him to inhale deeply. For a moment she feared she had misjudged him, that he might pass out before telling her anything. But Hassan did as he was told, as he had done all evening, and gave her a stoned smile as she went over to her fridge and opened the fast-freeze compartment.

An air steward on a late-night flight back from Abu Dhabi had once told her how to make a man sob with pleasure. He was gay, but he reckoned ‘the Narcissus’ worked for most men. It tapped into their fundamental egos, he said, particularly if they liked blowing hot and cold. Which was why, after Hassan’s initial cries of pain, Leila had moulded the solidifying wax around him. Once it had hardened, she had carefully slid it off and filled it with water. That water had now frozen, and was sitting upright next to a bag of peas. She peeled away the wax, looked at what she had in her hand with some satisfaction, and returned to Hassan in the bedroom.

‘Turn over,’ she said, unfastening his hand ties. It was time to find out what he knew about the marathon.

20

Spiro didn’t like the CIA sub-station in Warsaw. He didn’t like the coffee, he didn’t like the tired, 1970s hellhole of an embassy in which the Company was housed (an opinion confirmed when his driver took him past the glistening new premises of the British Embassy), but most of all he didn’t like the station chief. By rights, Alan Carter should have been fired years ago. He had messed up over the Agency’s post-9/11 rendition flights to Stare Kiejkuty, a programme based on tight cooperation between the CIA and the WSI. Its basis was total denial, but word had got out, and Spiro blamed Carter.

Now he had messed up again. Marchant’s release was in danger of sparking a three-way diplomatic row between Poland, America and Britain. Poland’s new prime minister had already been in touch, saying it had been a case of mistaken identity. His office had received reports of a Westerner at the remote airport, and a team of special forces had been sent over to take a look. When the Poles had come under fire, they had returned the compliment, and the detainee escaped. Spiro had never heard such bullshit, but there was nothing he could do. His allies in WSI were becoming increasingly powerless, and the protocol simply didn’t exist for lodging a complaint about a deniable project such as Stare Kiejkuty, particularly as it was meant to have been shuttered.

Spiro looked around at the bank of screens in the dimly lit room at the back of the US Embassy, a team of five junior officers keeping their heads down as he made his displeasure clear.

‘Do we have eyes at the airport?’ he barked at Carter.

‘We’ve picked up a feed from CCTV in immigration,’ Carter said. ‘We’ll see him if he’s got a passport.’

‘And the Brit Embassy?’

‘Still trying. It’s pretty secure over there.’

Unlike here, Spiro thought.

‘We’re also live at the station, and most of the city’s malls,’ said another officer.

‘What have we got on him?’ Spiro asked.

A photo of Marchant and Pradeep, running side by side in the marathon, was projected onto the wall in front of the computers. In the foreground, Turner Munroe, the US Ambassador to London, was clearly identifiable.

‘Close to his target, wasn’t he?’ Spiro said. ‘Too fucking close.’

‘Sir,’ one of the youngest officers asked tentatively, looking up at Carter for support. ‘Shouldn’t London be helping us on this one?’

‘Don’t even go there,’ Spiro snapped. ‘We’re flying solo, that’s all you need to know.’ He turned to Carter. ‘Where else might Marchant be heading? Krakow? The border? Why are we so sure he’s coming to town?’

‘We have an asset in a village four miles south of Stare Kiejkuty. He says an unmarked military truck drove through the village on the main road to Warsaw at fifteen hundred hours. Our guys at the airbase raised the alarm at twenty hundred last night, approximately five hours after Marchant was freed.’

‘Five friggin’ hours? What were they doing? R and R in the waterboarding pool?’

‘Sir, they had been drugged, bound and gagged by the Poles–they were Grom, elite special forces. It’s a credit to their training that they managed to free themselves at all.’

‘Is that right? Well, it isn’t a credit to your training that we have no fucking idea where Marchant is now.’

‘We’re into the city police’s traffic cameras,’ another officer announced, hoping to bail his boss out of trouble. They worked hard for Carter, and didn’t like to see him humiliated.

‘Screen one,’ Carter said. A moment later, black-and-white images of slow-moving traffic were being projected onto the main wall.

‘Gridlock,’ Spiro said. ‘Just like Route 28 after a Red Sox game.’

‘If the truck was coming into Warsaw, it would have entered the city on the Moscow–Berlin road,’ Carter said, looking over his junior colleague’s shoulder at the computer screen again. He was avoiding eye contact with Spiro as much as he could. The screen was split into three sections: the main traffic image, a city map, and a database displaying a list of camera positions throughout the city. ‘Switch to camera 17,’ Carter said. The junior officer scrolled down the list.

A new image, less grainy than the first, was projected onto the wall. The queue of traffic leaving the city was moving slower than the cars arriving.

‘How long does it take to get from Stare Kiejkuty to Warsaw by truck?’ Spiro asked.

Carter nudged the junior officer, who looked at his map again and zoomed out from the city to an image of the north of the country. A route highlighted in red wormed its way almost instantly from the airbase to Warsaw.

‘Two hours fifteen,’ Carter said, reading from the screen.

‘Can you get us into traffic archive?’ Spiro asked him.