Полная версия

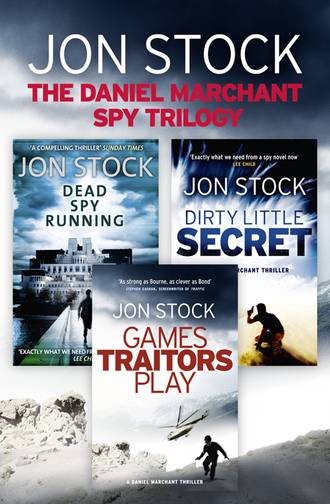

The Daniel Marchant Spy Trilogy: Dead Spy Running, Games Traitors Play, Dirty Little Secret

‘I hope the Americans see it that way. They never liked Stephen Marchant, and they don’t trust Daniel. I think it’s best neither of us mentions the chatter. It might not look too good for him.’

‘OK by me. I shouldn’t have told you anyway. The guys in Colorado Springs thought he was a bloody hero,’ Myers continued, draining his glass. ‘Any chance of kipping at your place for the night? Missed the last train back to Cheltenham.’

‘You can sleep on the sofa,’ Leila said, surprised by his confidence.

As they walked out onto the empty Embankment, looking for a cab, Leila turned to Myers. ‘You never thought it was true, what they said about his father?’

‘No. We would have known. We hear about everything at Cheltenham, sooner or later. It was political, expedient. They didn’t trust him. The PM. Armstrong. The whole bloody lot of them. Not because he was a traitor. They just didn’t understand him. He was old school, not their type.’

‘I sometimes wonder if there really was ever a mole,’ Leila said, looking out across the water towards Legoland, lit up in the night sky like some sort of rough-hewn pyramid.

‘It wasn’t Stephen Marchant, that’s all I know,’ Myers said, momentarily unsteady as he took in her legs. ‘Or his son. I can’t understand why they suspended him. No, Daniel’s one of the good guys. Good taste in women, too.’

Half an hour later, Leila lay on her bed, staring at the ceiling in her Canary Wharf flat, regretting that she had let Myers stay on her sofabed. He was already fast asleep, his body lying as if he had been dropped from a great height, and snoring loudly.

Leila thought again about her mother, how she had sounded on the phone the night before. The doctor who had first suggested a nursing home had told her not to worry, that she must expect her mother to sound increasingly confused, but it was still alarming. Sunday was not a day she usually called her, but the marathon that morning had left her frightened and tired. Alone in her flat, after four hours of questioning at Thames House, she had felt like a child again. When she was younger and needing to talk, she had never turned to her father, who had made little effort to know her. She had always confided in her mother, but now her voice had scared Leila even more.

‘They came tonight, three of them,’ her mother had begun in slow Farsi. ‘They took the boy–you know him, the one who cooks for me. Beat him in front of my eyes.’

‘Did they hurt you, Mama?’ Leila asked, dreading the answer. The confused stories of mistreatment grew worse each time she rang. ‘Did they touch you?’

‘He was like a grandson to me,’ she continued. ‘Dragged him away by his feet.’

‘Mama, what did they do to you?’ Leila asked.

‘You told me they wouldn’t come,’ her mother said. ‘Others here have suffered, too.’

‘Never again, Mama. They won’t come any more. I promise.’

‘Why did they say my family are to blame? What have we ever done to them?’

‘Nothing. You know how it is. Are you safe now?’

But the line was dead.

Leila wanted to be with Marchant now, to hold him close, talk about her mother. If only they had met in different circumstances, other lives. Marchant had often said the same. But their paths had tangled and could never be undone, even though both had learnt to keep a part of themselves back that no one–agents, colleagues, lovers–could ever touch. Marchant, though, was unlike anyone she had come across before. He was driven, pushing himself to the limits of success and failure. Nothing in his life ever happened in half measures. If Marchant drank, he would keep drinking until dawn. When he needed to sleep deeply, he could lie in until midday. And when he needed to study, he would work all night.

She remembered the day, two weeks into their new entrants’ course at the Fort, when she woke early after a fitful sleep. The wind had been blowing in off the Channel all night, and the old windows of the bleak training centre, a former Napoleonic fort on the end of the Gosport peninsula, were rattling like milk bottles on a float. The three female recruits were in a large, shared room on the north side of the central courtyard, while the seven men were in a block of separate bedsits on the east side, overlooking the sea. She went to the window and saw a light. She couldn’t be sure it was Marchant’s, but she pulled on a jumper, wrapped herself in a dressing gown and made her way quietly across the cold stone courtyard.

When she reached the row of men’s rooms, she knew immediately that it was Marchant’s weak light seeping out from under the old wooden door. She hesitated, shivering. The day before had been dedicated to the theory of recruiting agents. People could generally be persuaded to betray their country for reasons of Money, Ideology, Coercion or Ego: MICE. It had been a long day in the classroom, with only a brief drink in the bar afterwards. Marchant had studiously ignored her then, even though they had been in the same group all day, exchanging what she thought were meaningful glances.

She knocked once and waited. There was no sound, and for a moment Leila thought he must be sleeping; or perhaps he was partying down in Portsmouth and had left the light on as a crude decoy. But then the door opened and Marchant was standing there, in a faded surfer’s T-shirt and boxer shorts.

‘I couldn’t sleep,’ she said. ‘Can I come in?’ Marchant said nothing, but stood to one side, letting her step into the small room. ‘Aren’t you cold? This dump is freezing.’

‘It stops me falling asleep.’ Marchant picked up a pair of trousers that were slung across the unmade bed, dropped them in the corner and sat back down at his desk. ‘Make yourself at home. I’m afraid there’s only one chair.’

Leila perched herself on the edge of the bed. A pile of papers was stacked up on Marchant’s small desk, bathed in a pool of light from a dented Anglepoise. A half-empty bottle of whisky stood next to the papers. For a few moments they were silent, listening to the plangent wind outside.

‘What are you reading?’ she asked. He turned half away from her, flicking through the printed sheets.

‘Famous traitors. You know Ames is still owed $2.1 million by the Russians? They’re keeping it for him in an offshore account, should he ever escape from his Pennsylvania penitentiary. There was no higher calling, just the need for cash. His wife’s shopping bills were more than his CIA salary. So simple.’

‘It’s four o’clock in the morning.’

‘I know.’

‘Why now?’

Marchant turned back to look at her. ‘It’s not enough for me just to pass out of here. I need to fly out of this bloody place with wings.’

‘Because of who your father is?’

‘You heard the instructor yesterday. It’s quite clear he thinks I’m not here on merit. My dad’s the boss.’

‘That sort of thing doesn’t happen any more. Everyone knows that.’

‘He didn’t.’

Marchant turned back to his desk and looked out of the deep, stone-lined window. In the distance, the lights of an approaching Bilbao-to-Portsmouth ferry winked in the dawn light. Beyond it, on the far side of the main channel, he could make out the faint silhouette of the rollercoaster they had all been on two days earlier, as part of a team bonding exercise. Leila stood up, came over to him and started to work his shoulders. It was the first time she had touched him. He didn’t recoil.

‘You should get some beauty sleep,’ she said, close to his ear.

‘I didn’t mean to seem off with you tonight,’ he replied, lifting one hand slowly to hers.

‘You were with your friends, boys together. I should have left you to it.’

‘It wasn’t that.’

‘No?’

He paused. ‘I’m not going to be a particularly pleasant person to be around for the foreseeable future.’

‘Isn’t that for others to decide?’

‘Perhaps. But we’re spending the next six months learning how to lie, deceive, betray, seduce. I’m not sure I want what we might have mixed up with that.’

‘And what might we have?’ Leila asked. Her hands slowed.

Marchant stood up, turned and looked at her. His eyes were anxious, searching hers for an answer she could never give. She leant forward and kissed him. His lips were cold, but they were both soon searching for warmth before Marchant broke off. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, sitting down at his desk. ‘I must finish this tonight.’

‘You don’t sound very determined.’

‘I’m not.’

‘Shall I go?’

‘No. Stay, please. Get some sleep.’ He nodded at the bed.

Ten minutes later, she was tucked up under his old woollen blankets, struggling to keep out the cold, while he continued to read about motives for betrayal. He had bent the Anglepoise lower, to reduce the light in the room. She wondered if he could feel any heat from the lampshade, close to his cheek. The sea air was freezing.

‘What made you sign up?’ he asked, glancing in her direction. She managed a sleepy smile.

‘The need to prove myself, like you. Your father’s the Chief, my mother was born in Isfahan.’

Later, she was aware of him in bed next to her, holding her for warmth as sleet lashed the windows. She hoped that he was wrong about them, that what they might have could somehow survive the months ahead.

6

Marchant watched from his bedroom in the safe house as the train pulled out from the village for London. He thought again of Pradeep dying on the bridge. For a moment he wondered if one of the two bullets had missed its intended target. Did they mean to shoot him as well as Pradeep? It was the right moment to fire–Pradeep collapsing in his arms–if they weren’t bothered about collateral.

Below him a Land Rover was making its way along the road that ran along the valley. He assumed it was heading into the village, but the driver turned off onto the track that led up to the safe house. It was a tatty, dark-blue Defender, and as it bumped its way towards the house, Marchant could make out the local electricity board’s logo on both sides. Downstairs he could hear movement. His babysitters were stirring, ready to confront the driver, play out whatever cover story they had been given.

Next to the safe house was a small electricity sub-station for the village, enclosed by spiked green metal fencing and with its own orange windsock, billowing gently in the early-morning wind. The compound also housed an old nuclear bunker. A small sign, put up by the local history society, explained that it was used by the Royal Observer Corps during the Cold War, and could house three people for up to a month.

The surrounding area was all fields. Marchant assumed that the Land Rover belonged to the electricity board’s maintenance staff. It must be a routine check on the sub-station, he thought, but as it parked up below his window, he recognised the man who stepped out of the front passenger seat. It was Marcus Fielding, his father’s successor.

From the moment he had joined the Service, fifteen years earlier, Fielding had been marked out as a future Chief. The media had branded him the leader of a new generation of spies, Arabists who had joined after the Cold War and grown up with Al Qaeda. They had learnt their trade in Kandahar rather than Berlin, cutting their teeth in Pakistani training camps rather than Moscow parks, wearing turbans rather than trenchcoats.

‘I don’t suppose anyone has actually thanked you yet,’ Fielding said, as they walked down a path in the Savernake Forest. Marchant wasn’t fooled by the bonhomie. Fielding had always been supportive of Marchant, dismissing his suspension as a temporary setback in the escalating turf war between MI5 and MI6. But the events during the marathon would have tested his loyalty, ratcheting up another notch the tension between the services.

All around them rainwater dripped off the leaves, resonating like polite applause through the trees. Marchant glanced back to where the Land Rover was parked. Two men from the safe house stood quietly at the foot of a monument to George III which rose out of a clearing in the woods.

‘It was quite a show you put on,’ Fielding continued. ‘Saved a lot of lives. The Prime Minister asked me to pass on his personal thanks. Turner Munroe will be in touch, too.’

‘He probably just wants his watch back. MI5 weren’t quite so appreciative.’

‘No, I’m sure they weren’t.’

They walked on together for a while through the ancient wood, watched by its sentinel oaks. Fielding was lean and tall, professorial in appearance, with a high, balding forehead and hair swept back at the sides. His face was oddly childish, almost cherubic. To compensate, he wore steel-rimmed glasses, which added to his donnish air and broke up the expanse of forehead. Colleagues had been quick to dub him the Vicar. He had been a choral scholar at Eton, and it was easy to imagine him still in a cassock and collar. He didn’t drink, nor was he married. Prayer, though, had played little part in his rise to the top.

‘I’m sorry about Sunday,’ he continued. ‘We tried to get you out of Thames House as soon as we could, but, well, you’re not strictly our man at the moment. MI5 insisted you were their guest.’

‘You would have thought I was the one wearing the belt.’

‘Nothing too unpleasant, I hope?’

‘Six hours of amateur Q and A. First they suggested I was helping the bomber, then they thought it was a set-up by MI6 to get my job back. No wonder they didn’t see it coming.’

‘That’s just it, I’m afraid. The whole incident doesn’t reflect well on them. Or on us, to be honest. Everyone had assumed that last year’s attacks were over. No one saw it coming. You’re certain he was from South India?’

‘Kerala, born and bred.’

‘We were all hoping that threat was over. The one person to come out of this with any credit is you, and you shouldn’t have been there.’

‘Can’t it be spun as a general intelligence-led operation?’

‘The media’s not the problem. It’s the PM. He can’t understand why a suspended officer was all that stood between a marathon and carnage. I’m not sure I fully understand either.’

That had always been Fielding’s way: his subjects rarely realised that they were being interrogated, such was his seeming politeness. But just when you had dropped your guard, he hit you hard with a disguised uppercut of meticulous accuracy.

‘Leila signed us up at the last minute. A friend of hers works for one of the sponsors. It was stupid, we hadn’t done enough training. On race day, I saw a dodgy belt and did something about it. I’m beginning to wish I hadn’t.’

‘And you had no warning? You’ve heard that Cheltenham picked up some chatter on the Saturday?’

‘No warning, no.’ There was little point in mentioning Leila, he thought. It would sound wrong, as if she had said more than she had, when in fact she had barely told him anything. It had been a passing remark, no hard information. It worried him, though, that Fielding also doubted that it had been an entirely chance encounter.

‘I couldn’t have done it without Leila,’ Marchant added. ‘You know that?’

‘She did very well. A bright future should lie ahead of her. Ahead of you, too, if that’s what you want.’

Marchant knew Fielding was referring to his behaviour of the past few months, when old demons had broken free again, unchecked by the discipline of intelligence work. Fielding stopped at one of the Savernake’s oldest oaks. Storms had removed the upper boughs, leaving only the trunk, strained and contorted, as if in pain. He bent down to look at the base of the tree, putting one hand to the small of his back. Sometimes his pain was so severe that he would take to lying down in his office, conducting meetings supine.

‘Spring morels,’ he said, pulling aside some brambles to get a better look. Marchant stooped to study them more closely. ‘Exquisite fried in butter.’ Everyone in Legoland knew how seriously Fielding took his food. An invitation to one of his gourmet dinners at his flat in Dolphin Square was better than a pay rise. He stood up again, both hands now pressed against his back, as if he was about to address his congregation. They both stared out across the woods, the sun streaming through gaps in the canopy, forming spotlit pools of limelight on the forest floor.

‘Tell me, are you still committed to pursuing your own inquiries into your father’s case?’

Marchant didn’t like his tone. In a quiet moment at his father’s funeral, two months earlier, Fielding had told him to let his office know if he turned up anything. All he had asked was that he went about his inquiries quietly. Become another whistleblower like Tomlinson or Shayler and he would throw the book at him. His father would have said the same: he despised renegades too. Only once had Marchant lost it, at a pub near Victoria, when an evening had ended in a brawl. A junior desk officer had been dispatched to the police station to release him and smooth things over.

‘Wouldn’t you want to know what happened?’ Marchant replied.

‘I have a pretty good idea already. Tony Bancroft has almost finished his report.’

‘But he’s not going to clear my father, is he?’

‘None of us wanted him to go, you know that? He was a much-loved Chief.’

‘So why did we let MI5 get one over us? There was never any evidence, no proof against him.’

‘I know you’re still angry, Daniel, but the quickest way to get you working again is for you to keep your head down and let Tony finish his job. MI5 don’t want you back, but I do. Once Bancroft is on record saying you pose no threat, there’s nothing anyone can do about it.’

‘But Bancroft won’t clear my father’s name, will he?’ Marchant repeated.

They walked on, Fielding a few yards ahead of him. Marchant had met with Lord Bancroft and his team, answered their questions, and knew that he had no case to answer. He knew his father was innocent, too, but the Prime Minister had needed someone to blame. Mainland Britain had been subjected to an unprecedented wave of terrorist attacks during the past year. Nothing spectacular, but there was enough public fear to keep MI5 on a critical state of alert: electricity sub-stations, railway depots, multi-storey car parks. The evidence soon pointed to a terrorist cell based in South India, drawn from workers who had taken poorly-paid jobs in the Gulf.

The pressure to nullify the threat had grown, but the terrorists always seemed to be one step ahead. Soon the talk was of a mole, high up in MI6, helping the hunted. Daniel’s father had become obsessed with the theory, but he had never managed to prove it, or to halt the bombings. Suspicion had finally fallen on him. When his position as Chief became untenable, the Joint Intelligence Committee, guided by Harriet Armstrong, MI5’s Director General, recommended that he be retired early. The attacks had stopped.

Fielding paused at the point where their path met another. As Marchant joined him, they instinctively looked both ways before crossing, even though the forest was empty. A muntjac deer barked in the distance.

‘Are you still drinking?’ Fielding asked.

‘When I can,’ Marchant said.

‘I’m not sure we can bail you out a second time.’

‘How long will I be kept at the safe house?’

‘It’s for your own security. Someone out there’s not happy you thwarted their attack.’

They walked on together, both at ease with the forest’s noisy dampness. ‘There are no surprises in what I’ve read of Bancroft’s report, no moles uncovered,’ Fielding said, as they began on a loop back towards the car. ‘It’s not Tony’s style, not why he was appointed. Just a summing up of what happened on your father’s watch and a measured assessment of whether anything more could have been done. There were too many attacks, we all know that.’

‘And someone had to take the bullet.’

‘The PM’s a former Home Secretary. He was always going to favour MI5 over us.’

Marchant had heard all this before, but he knew from Fielding’s manner that he was holding something back.

‘Unfortunately, the Americans have been pushing for more, day and night, trying to establish that it was conspiracy rather than complacency on your father’s part. We’ve resisted, of course, but the PM is indulging them. And now it seems they’ve persuaded him to hold back on the report’s publication, saying the CIA have something specific.’

‘On my father? What?’

‘How much do you know about Salim Dhar?’

‘Dhar?’ Marchant hesitated, trying to think clearly. ‘On the shortlist for masterminding last year’s UK bombings, but no evidence to link him directly. Always been more anti-American than British. It’s a while since I read his file.’

‘Educated in Delhi, the American school, then disappeared,’ Fielding said. ‘The Indians arrested him two years later in Kashmir, and banged him up in a detention site in Kerala, where he should be now. Only he isn’t.’

‘No?’

‘He was one of the prisoners released in the Bhuj hijack exchange at the end of last year.’

It wasn’t his region, but Marchant knew the incident had been an almost exact copy of the Indian Airlines hijacking at Kandahar in 1999. Then, Omar Sheikh had been released, amid much international condemnation. It was never made public who was freed at Bhuj.

‘AQ must have rated him,’ Marchant said, wondering where his father fitted in.

‘We had Dhar down as a small-time terrorist until Bhuj. They wanted something spectacular in return for his freedom. Within a month, Dhar was launching RPGs into the US compound in Delhi.’

Marchant had read about the attack, in the blur of grief. It had taken place just after his father had died, before the funeral. Nine US Marines had been killed.

‘What’s this got to do with my father?’

Fielding paused before answering, as if in two minds whether to proceed. ‘The Americans would very much like to find Salim Dhar. After Delhi, he went on to attack their compound in Islamabad, killing six more US Marines And now the CIA has established that a senior-ranking officer from MI6 visited Dhar in Kerala shortly before he was released in the hostage exchange.’

Marchant looked up. ‘And they think it was my father?’

‘They’re working on a theory that it was, yes. I’m sorry. There’s no official record of any visits. I’ve checked all the logbooks, many times.’

Marchant didn’t know what to think. It wouldn’t be unusual for the local station head from Chennai, say, to bluff his way into seeing someone like Dhar, but it would be extremely unorthodox for the Chief of MI6 to make an undeclared visit from London.

‘In the context of MI5’s own inquiries, I’m afraid it doesn’t look good,’ Fielding added. ‘There are those who are convinced that Dhar masterminded the British bombings, despite his preference for killing Americans.’

‘What do you think?’ Marchant asked. ‘You knew my dad better than most.’

Fielding stopped and turned to Marchant. ‘He was under a lot of pressure last year to clean up MI6’s act. The talk at the time, remember, was all about an inside job, infiltration at the highest level by terrorists with some sort of South Indian connection. Even so, why talk to Dhar personally?’

‘Because he couldn’t trust anyone else?’ Marchant offered. For whatever reason, he knew that it must have been an act of desperation on his father’s part.

‘The good news is that details of this visit haven’t crossed Bancroft’s desk yet, and they might never,’ Fielding said. ‘His job was to draw a line under your father’s departure, not to open the whole affair up again. He’ll need to be sure of the evidence before presenting it to the JIC, and there isn’t a lot at the moment.’

‘Is there any?’

‘Dhar’s jailer, the local police chief in Kerala. Someone blackmailed him to gain access to Dhar. It had all the hallmarks of an old-school sting.’

‘Moscow rules?’

‘Textbook. Indian intelligence found the compromising photos hidden in the policeman’s desk drawer. They were taken with one of our cameras. An old Leica.’ He paused. ‘The last time it was checked out was in Berlin, early 1980s. Your father never returned it.’