Полная версия

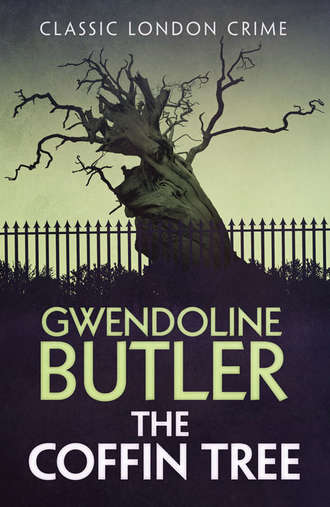

The Coffin Tree

‘We have a problem, Archie,’ thought Coffin, but he did not say it aloud. Instead: ‘I’m not happy.’

‘Who could be?’

‘Felix Henbit had a wife.’ He made it a statement; he had liked Felix but kept his distance.

‘Yes, likewise Pittsy; not long married. Also a sister in Cleveland who seemed a bit remote.’

‘I’d like to meet Mrs Henbit.’

‘I think you should. She’d appreciate it, a nice girl who’s bearing up well. All the usual support groups have been in touch to see how she was getting on.’ Mary Henbit had been bleeding inside but hadn’t let it show too much.

‘I’ll get round there.’ He might take Stella if she ever came home again which he sometimes doubted. She was good on such occasions, other women liked her.

Coffin looked down at his plate of chips. Not my mother, vanishing lady, my mother, you’d be home alone. She’d be long dead now. Or was she? His mother seemed just the sort to read you could live to be a hundred and sixteen and decide to do it. He pushed his plate away; the chips didn’t appeal so much.

The two men talked for a while longer, then Archie Young went off – still flushed with the news of his promotion, and wishing his wife was at home so that he could tell her – soon after the meal was finished. Promotion had come very quickly; he knew he owed a lot to the chief commander, but he also knew he was a good officer.

He didn’t have the older man’s imagination, and sometimes he thought the Big Man let the parameters of his imagination spread a mite too far. He was thinking that now.

Coffin had not told Archie Young all his thoughts even though he trusted him. He never did tell anyone everything. He had seeded the corn and must now await events.

Later, on the day of her interview, while Phoebe prepared herself for it and then went through it and got a hint of her success; and while Coffin sat thinking of his own problem – all this while the fire burned in the rough ground beyond the old Atlas factory.

When did it start? It must have started in the early afternoon because such fires burn slowly. The fire burned the mound of wood and leaves which a sexless figure put together, which he or she had lit and upon which, so a watcher said later, he or she had climbed. Hard to believe and the witness did not have good eyesight. Not climbing, perhaps, but dragged?

First smoke, then flames.

The body burned, the hair smouldered, the body fats caught and melted, the skin crisped.

Phoebe, who knew she had interviewed well, who was sure she had got the job, waited for Coffin to telephone her, and when he did not, tried to telephone him at home. He was not there so she left a message on his answering machine.

Phoebe came back into the picture and Stella returned to the fold on the same day, which was a complication. Both of them left a message on his answerphone.

Flying back today, fondest love, Stella. Get out the champagne. That meant she was in a good mood. Not necessarily forgiving (what was there to forgive, he asked himself), but certainly loving.

Phoebe Astley made her plea. Can you give me a bell? I am staying with a mate who has a place near the Tower. We could meet for a drink. I mean we’d better, hadn’t we? We’ve got to talk.

Coffin smiled wryly as he put down Tiddles’s food and pushed the dog’s nose out of the way. Phoebe always had rotten timing, that was one thing he now recalled about her. Stella, on the other hand, had the impeccable timing of a top actress.

Well, he would ring Phoebe, but in his own time; Phoebe had to learn about timing, and now it was Tiddles and the dog who came first.

He fed them both, washed his hands, because cat food (they both ate cat food, fortunately the dog could not read) smelt.

‘The thing is, Tiddles,’ he said. ‘To be quiet but not furtive.’ He considered the problem while he fed the dog.

‘I know: we’ll go to the Half a Mo.’ He was pleased with Phoebe and his own plans. As he left the interview room – without speaking to her – he had seen her talking to his assistant. She had a carrier bag from Minimal at her feet. Good girl, he had thought. Instinct, that’s what she’s got. Without knowing it, she has started work for me.

The pub, called Half a Mo by its regulars was placed on the junction by Halfpenny Lane and Motion Street, outside Coffin’s bailiwick and into the City of London.

Small and dark, it had always been popular with those seeking privacy. Coffin had arrested more than one villain there in the old days. Its real name, shown on the board swinging above the door, was the King’s Head, and there was a bearded head wearing a crown and clutching a glass to be seen, although wind and rain had weathered it. Only strangers to the district called it by that name.

The Half a Mo had changed since Coffin’s last visit. It had been brightened up, more lights, more paint, more noise. It had never been noisy, as he remembered it; people had muttered quietly over their drinks. Usually because they were up to no good. Now music blasted from several sources, but, as he reflected, this too was a good protection against conversations being heard.

In fact, he could hardly hear what Phoebe was saying; she had kept him waiting, which just confirmed what he thought about her timing.

She was sitting opposite him, looking bright-eyed and alert, and a good deal thinner than when he had seen her last year in Birmingham, where she had helped him through a difficult patch. She looked thinner, but that might be due to a smart-looking silk dress she was wearing.

‘How are things now?’ She lifted up the gin and tonic which had always been her tipple.

It was a routine question to which no answer need be given.

‘Fine,’ he said. Which was half true and half not true. He had survived a board of inquiry, some hostile media criticism, and been told that he could be sure of a KBE in the next Honours list. Also, he still had a wife, at least he thought so; he would know more about that when he met Stella off the plane tomorrow morning. ‘And what about you?’ Their past relationship meant that there was real feeling in the question.

‘Oh well, as you say, fine …’ She sipped her gin and looked away.

‘I was surprised when you put in for the job.’

‘I heard about it on the grapevine and thought it was one for me … Of course, I didn’t know much about it then, it was just a whisper.’ Now she did know. Or as much as he had told her and as much as she had guessed.

‘What about your husband and the children and the dog – do they like the idea of your working in the Second City?’

Phoebe looked away. ‘Do you like my dress? It’s new, I bought it to celebrate getting the job. I know I have got it; I was tipped the wink.’

‘Come on, Phoebe.’

‘They don’t exist; there is no husband, no children, not even a dog. I made them up. But I expect you know that.’

‘I did check.’ He looked at her without a smile. ‘Why, Phoebe, why?’

She shrugged. ‘Well … I didn’t think I’d ever see you again after you swung into my office that day in Sparkhill, you hadn’t answered my party invitation. You just came in because you wanted help. And you looked so married.’

‘I didn’t know that. I didn’t know being married changed the looks.’

‘Well, it’s changed yours. And for the better, I may add.’

Coffin just stopped himself looking at his reflection in the wall mirror. ‘But you were doing very well in the West Midland force.’

‘You checked that too?’

He was silent.

‘Of course you did, you’re a thorough man, John, always were … I suppose I will have to call you Chief Commander and Sir now.’

‘You needn’t call me anything.’

‘I have called you some names in my time.’

‘Sorry, Phoebe. I expect I deserved them.’

‘I’ll tell you one day how much you deserved them.’

Coffin felt his spirits sinking. ‘I hope we are going to be able to work together.’

Phoebe moved sharply. ‘Will we be? I’ll be heading my own little unit and you are the big boss.’

‘I’ll explain.’

‘Perhaps you had better … When you telephoned in Sparkhill after I applied for the position, I knew you wanted me. I don’t say you fixed getting me the job, although you could have done, but you didn’t do it for love of me, so what else is there?’

First of everyone, she had caught on to the hidden agenda.

‘I knew you were the right person.’ He got up. ‘What about something to eat? The food used to be reasonable here, and I’m hungry.’

When he came back with a plate of sandwiches, Phoebe said: ‘I was surprised when I got a packet of photocopied advertisements from Second City News … A couple of dress shops, a fast food chain, not one I knew, two hairdressers … I didn’t think shops were touting for my custom, and then I remembered a copper who had sent me an advertisement for a new restaurant with the date and time and question mark scribbled on it and I thought, well, I know someone who does that sort of thing. Perhaps when he doesn’t want to commit himself too much.’

Coffin offered her the sandwiches. ‘Cheese or ham?’

‘Cheese. And then I thought: But, the John Coffin I knew was never anonymous about work.’

‘I’ll take the ham then. Pickle? I remember you liked it.’

‘Not onions though. You have to know someone very well to breathe onion over them. Of course, I do know you well, or I did. I thought: whoever sent those papers to me was nervous. And the John Coffin I knew was never nervous without cause.’

‘I always valued your powers of observation and deduction. You are the right person for what I want.’

‘Yes, but what is it? I am to run a small unit which will communicate with all principal institutions in the Second City. I shall have the rank of chief inspector, which I am glad about, by the way, but not much money to spend.’

Coffin looked about the bar which was crowded, but no one was taking any interest in them in their seat by the window where they could not be overheard.

‘Yes, you will be all that, and the unit and your position were not invented for you, but as soon as your name appeared as an applicant, I decided to make use of you.’

‘Oh, thanks.’

He ignored her sharpness – it was part of Phoebe. ‘Let me explain: large sums of dirty money, money from drugs, and crime, are being put through the City of London banks. We are getting our share. This is seen as threatening and damaging.’

Phoebe, listening, absently popped a pickled onion into her mouth. ‘But I’m not a financial –’ she began.

‘Stop and listen, the financial side is being handled by the Met and the City of London squad working with the Second City fraud experts … We’re only small but I’ve recruited some good brains.’

Phoebe choked on the onion and Coffin stood up to hit her on the back.

‘Oh, come on, Phoebe, listen. You will have two juniors working with you. Your ostensible job will be to liaise with all the institutions in the Second City, you know that, that was your remit.

‘But I am going to use you in another way.’ He moved the dish of onions away so that she could not get at them. ‘Some money is being laundered, here in the Second City. Where, we can guess; from that we can move to guessing by whom, but they are getting help from someone close to us.

‘Two of my young men who were working on it are dead. Felix Henbit and Mark Pittsy. Felix was a clever and resourceful officer; Pittsy was brilliant – he would have gone right to the top. Both of them died in what were supposed to be accidents. The papers that I sent you came to me anonymously. I don’t know if they have a connection, or who sent them but I sent them on to you. Not exactly anonymous; I thought you’d guess they were from me, but I didn’t want to make any comment; I wanted you to take them cold and react.’

Phoebe looked down at her new dress. ‘They took me into Minimal.’

‘That may have been exactly the right thing to do.’

Phoebe remembered some of the other names: Dresses à la Mode, KiddiTogs, Feathers and Fur. ‘You may have to give me a dress allowance if I’m to shop at all of them.’ But probably they were not all as expensive as Minimal; the names suggested different markets, and Feathers and Fur might be quite specialized.

Coffin ignored this; life with Stella had taught him caution when discussing money spent on or for clothes. ‘What we have here is a classic murder puzzle: someone is picking off my men. I don’t think that Felix Henbit or Mark Pittsy died because they had drunk too much; coppers do drink, but those two were careful men. Somehow they were killed.

‘I’m not sure of what the motive is: whether it was because they were close to me, or because they had enemies I know nothing about, but I feel the motive must lie in the financial investigations they were both working on. I want you to investigate their deaths.’

‘Don’t you trust your own men?’

Coffin was silent. ‘I have built a good structure up here. I took over a rambling set of CID and uniformed units and I’ve built up a force with its own identity. But I’ve had to do it on the quick. Of course I trust them but this is murder in my own backyard. I want you to investigate it for me.’

‘I see.’

‘You will have yourself and you will have me.

‘My own feeling is that someone is protecting the machine that is feeding the illegal money into this area. We have a Minder, and I want him or her caught. I want you to identify the Minder.’

Phoebe considered, she knew now what she was taking on. ‘I shall want back up. Leg work, help with interviews …’

‘You’ll get it.’

‘Forensics …

‘You’ll get it. Once we identify the Minder, then we will get the proof.’

Phoebe’s mouth went dry. ‘I never thought I’d hear you put it that way round.’ For the first time, she saw the metal in John Coffin. ‘I think you’d better get me another drink because I see what I am; a kind of stalking horse. If I succeed at all you want, I stand a good chance of getting killed myself.’

When he came back with her drink, she noticed he had got one for himself too and it looked strong. Good, at least he cared something for her. ‘I almost wish I hadn’t put in for the job.’ She looked down at her new black dress, the colour of which now seemed uncomfortably appropriate.

‘Phoebe, why did you apply? The truth now. I want you for this job, confirmation has to go through channels, but I’d like you here now. Only I need to know why you wanted to come.’

The drink lessened the dryness in her mouth. ‘Oh well, you might as well know: I put away a rough type with a long record who threatened to get me personally, if you know what I mean … He comes out about now. Could be out already. I thought I’d be better off down here in the Smoke where he wouldn’t have the contacts.’

Coffin considered. ‘Doesn’t sound like you, Phoebe.’

She looked out of the window. ‘Well, there was a sort of an affair.’

‘Ah, yes, that would complicate matters. So it got personal … He still wants you?’

There was a long pause. ‘It wasn’t quite like that. You see the affair, such as it was, was not with him but his wife.’

‘Now I am surprised.’

‘It was something that just seemed to happen … I wasn’t too happy, neither was she, poor girl, but for me, it was a mistake.’

‘Only not for her?’

Phoebe nodded. She was thinking about Rose with sadness and liking, but not love, not physical love. ‘No. I’m afraid I treated her badly. You might be surprised to learn that treating their lovers badly is not the prerogative of men.’

Stella herself could not have delivered a shrewder blow. ‘So you’ve run away?’

‘I’ve run away. Don’t we all?’

As they talked, the fire had been quenched and the blackened shrivelled body found; from one hand an unburnt finger stuck up as if in accusation.

The inhabitants of this particular area were few – a small terrace backed on to the open ground – moreover, they had among them the eccentric figure of Albert Waters who had built a small replica of Stonehenge in his back garden and who was now erecting the Tower of Babel in the front. They took it for granted that this fire was something to do with him.

He was into suttee now.

2

A quiet buzz sounded in Coffin’s pocket. ‘Damn! I’ve been summoned.’

‘Still attached to your bleeper?’ said Phoebe.

‘As ever.’ He also had a portable telephone but he preferred a call such as this and then to go to his car phone. More protected.

Phoebe raised an eyebrow, a sceptical gesture she should have denied herself when she knew how much she was going to depend on him. ‘I thought with your new eminence you would have given that up.’ He wasn’t a man who minded being laughed at, not as much as most men, but you couldn’t go too far. In the past she often had.

He stood up. ‘I must go to the car. How did you get here?’

‘I walked.’ I was on the verge of going too far, she thought, I must remember, I must remember.

‘I’ll give you a lift back.’ To where you are staying, he meant, wherever that was.

She would have known his car from any other man’s as soon as she looked at it. Nothing flamboyant: a good dark-coloured Rover, you could tell he had some money; he hadn’t had once, but always bought the best he could afford whether it was a car or a coat. No litter in the car, but a neatly folded raincoat on the back seat with a pile of road maps. He liked to know where he was going. She had used to wonder why he didn’t carry a compass as well. Not a joke to make now. He was quieter and more controlled than he had been once, gentler perhaps, but in a grim mood. He was angry.

In the car he listened to Archie’s voice. ‘I don’t know if you want to come, but you need to know. A body on a bonfire, looks deliberate.’

Phoebe watched and listened as Archie poured out his words. There was a faint scent on the air: Stella, she thought, her scent, and was horrified to feel a stab of jealousy. She was wearing Giorgio herself: strong, assertive and sexy and she had better give it up because if you want to be anonymous, and professionally this might be wise at the moment, then this was not the scent to wear. People remembered it. What Stella’s scent was, she could not recognize.

‘Is it still burning? Under control? But the body? Yes, I get it.’

Whatever Superintendent Young had to say did not please the chief commander because Phoebe saw him frown.

‘Right, I’m coming. I want to take a look for myself.’ He turned to Phoebe. ‘You’d better come along too. There is a fire and a body and it doesn’t look like an accident. And an old man I know seems to have something to do with it.’

He looked at Phoebe’s smart dress. ‘Will you risk that? You can never tell when you go to an incident.’

‘I’ll risk it … Did you notice – no, I don’t suppose you did – that the large woman on the committee was wearing another version of this dress in red?’

‘That was Geraldine, she always wears red when she’s on the warpath.’

Phoebe blinked. ‘And was she?’

‘She must have been. Powerful lady, Geraldine. Keep on her right side if she comes your way.’

‘And will she?’

‘Can’t tell. She knows the district pretty well. I think she may even know old Waters, the man who seems to have something to do with this new body.’

‘It doesn’t connect with that other business?’ She would always refer to the problem in this elliptical way from now on. ‘Only connect,’ E. M. Forster had said; he ought to have been a detective, she thought.

‘I hope not, or the whole thing will be even crazier than it is now, but who knows, he’s a strange man, but no, I don’t see a connection … Superintendent Young is there and he is one of the people you’ve got to know.’

And to get on with, Phoebe interpreted this as meaning. ‘I know something about him already. I know he worked with you before you came here, that he’s got a good record, that he’s done two courses at Saxon Police College, and always come out among the first half dozen, but that he always says his wife is the clever one.’

Coffin started the car. ‘You have done your homework.’ But he had expected no more of her and would have done the same himself in her place. She had perhaps demonstrated to him the range of her contacts, which interested him, and made him wonder who was using whom in this new appointment.

‘I’ve met his wife, by the way.’

‘How was that?’

‘Oh, just by chance, at a meeting in Birmingham University: she was the guest speaker.’

‘Interesting, was it?’ He was guiding the car through the traffic which was unexpectedly heavy on this hot evening where the going down of the sun had not lowered the temperature much. He glanced at Phoebe’s dress, there wasn’t much of it, so she was luckier in the heat than he was.

He didn’t believe for one minute that she had met Alison Young by chance; she had gone to the meeting on purpose, part of her pre-planning.

‘Yes, it was interesting.’

Archie Young was not himself an interesting speaker although it was well worth listening to what he had to say. He got his facts right.

He turned left at the traffic lights, leaving the busy main road through the Docklands behind him and driving into a side street lined with small houses with neat front gardens: Palgrave Drive. Beyond Palgrave Drive was Frances Street which was less neat, and from Frances Street he drove down the poetically named Golden Alley. Golden Alley was not neat at all since several old cars and various abandoned shopping trolleys had been left there to rust, next to a gas cooker of antique appearance.

‘We are in Swinehouse now and you’d better get to know it.’ He was driving slowly. ‘When can you start?’

‘I’ve already asked for a transfer. I have some leave. Straight away, if you want.’

‘It’ll have to be unofficial, but that suits me; I want you here, working for me, quietly.’

‘OK. Suits me too.’

‘Where will you live?’ The car was bumping over cobbles. The only good thing about Golden Alley was that it was short, it led into Brides Street. Every time Coffin came this way, he thought that if a modern Ripper got going (and praise be, it would not be in his time and his bailiwick) it would be in Brides Street. Brides Street was narrow, lined with houses in which people lurked rather than lived.

‘I’ll look around. Rent something till I sell my place in Edgbaston.’ She looked out of the window with interest. There seemed to be property for sale and to let around here. And she had not forgotten Eden Brown’s invitation: she liked Eden and it would be interesting to start off with her. She did not anticipate staying, she’d need her own place in the long run. But Eden was clearly quite a girl.

You could smell the fire now.

Brides Street wound its way into Fashion Street where, by contrast, the houses were pretty and well painted. Coffin came this way at irregular intervals to visit an interesting old inhabitant called Waters who had built Stonehenge in his garden. The neighbours had complained, so he removed his Henge, stone by stone, and built a pyramid in the back instead with an attempt at the Tower of Babel. His pyramid had a little door and Mr Waters lived in it himself when he felt like it, as did several itinerant cats and an old urban fox.

Behind Fashion Street was a stretch of rough ground in which Albert Waters sometimes operated and where he had once built a mini earthwork that he called Waters’s Way. Beyond the now weed-overgrown earthwork, lay the Swinehouse football ground.

In the rough ground, was the fire.

A fire engine, an ambulance and several police cars blocked their way. A small crowd was penned behind a police barrier.

‘I smelt a fire burning when I was shopping,’ said Phoebe.

‘Yes, Calcutta Street, where you were, is parallel with Fashion Street but nearer the river. The wind must have been blowing your way. It’s a funny district, I’ve smelt some weird smells there myself, almost as if the past had caught alight and was burning.’