Полная версия

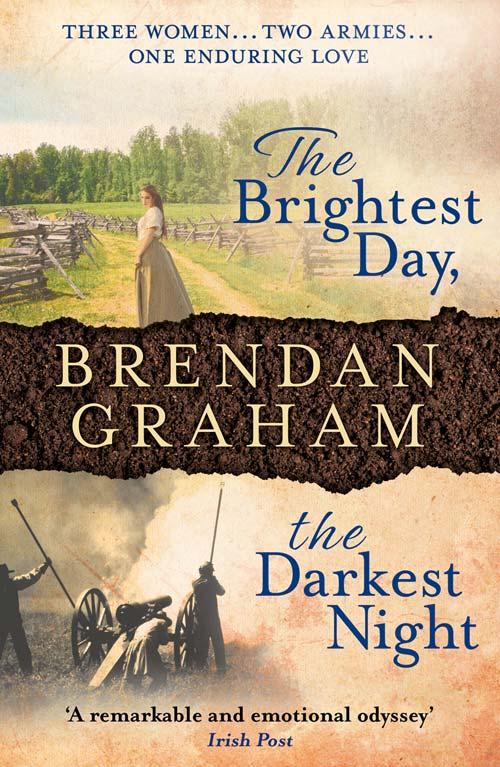

The Brightest Day, The Darkest Night

BRENDAN GRAHAM

The Brightest Day,The Darkest Night

COPYRIGHT

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2005 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Brendan Graham 2005

This edition 2016

Fair-Haired Boy - Words and Music by Brendan Graham © Brendan Graham (world exc. Eire) / Peermusic (UK) Ltd. (Eire)

Praise to the Earth - Words and Music by Brendan Graham © Brendan Graham (world exc. Eire) / Peermusic (UK) Ltd. (Eire)

Ochón an Gorta Mór - Words and Music by Brendan Graham © Brendan Graham (world exc. Eire) / Peermusic (UK) Ltd. (Eire)

Sleepsong - Words: Brendan Graham; Music: Rolf Lovland © Peermusic (UK) Ltd.; Universal Music A/S

Crucán na bPáiste: Words & English Translation: Brendan Graham; Music Trad/Additional Music - Brendan Graham © Brendan Graham (world exc. Eire) / Peermusic (UK) Ltd. (Eire)

I Am The Sky: Poem by Brendan Graham

The Last Rose of Summer - Thomas Moore - A Selection of Irish Melodies, Vol 5 (1813)

Has Sorrow Thy Young Days Shaded - Thomas Moore - A Selection of Irish Melodies, Vol 6 (1815)

Brendan Graham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Source ISBN: 9780006513971

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007387687

Version: 2016-01-19

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

DEDICATION

Mary

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

PROLOGUE

ELLEN

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

PATRICK

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

FORTY-TWO

FORTY-THREE

FORTY-FOUR

FORTY-FIVE

FORTY-SIX

FORTY-SEVEN

FORTY-EIGHT

FORTY-NINE

FIFTY

FIFTY-ONE

FIFTY-TWO

FIFTY-THREE

FIFTY-FOUR

FIFTY-FIVE

FIFTY-SIX

FIFTY-SEVEN

FIFTY-EIGHT

LAVELLE

FIFTY-NINE

SIXTY

SIXTY-ONE

SIXTY-TWO

SIXTY-THREE

ELLEN

SIXTY-FOUR

SIXTY-FIVE

SIXTY-SIX

SIXTY-SEVEN

SIXTY-EIGHT

SIXTY-NINE

SEVENTY

SEVENTY-ONE

SEVENTY-TWO

SEVENTY-THREE

SEVENTY-FOUR

SEVENTY-FIVE

SEVENTY-SIX

SEVENTY-SEVEN

LAVELLE

SEVENTY-EIGHT

SEVENTY-NINE

EIGHTY

EIGHTY-ONE

EIGHTY-TWO

EIGHTY-THREE

EIGHTY-FOUR

EIGHTY-FIVE

ELLEN

EIGHTY-SIX

EIGHTY-SEVEN

EIGHTY-EIGHT

EIGHTY-NINE

NINETY

NINETY-ONE

NINETY-TWO

NINETY-THREE

NINETY-FOUR

NINETY-FIVE

NINETY-SIX

NINETY-SEVEN

NINETY-EIGHT

KEEP READING

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

AUTHOR’S NOTES

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

Half Moon Place, Boston, 1861

Ellen O’Malley opened her eyes.

Blinked.

Raised her head.

Waited, watching for the sky.

Soon the sun would come creeping into the corners of Half Moon Place. ‘Like a broom,’ she thought. Sweeping out the dark.

When the sun brushed along the narrow alleyway towards where she sat, she opened her throat, and began singing,

‘Praise to the Earth and creation,

Praise to the dance of the morning sun.’

She sat atop a mound of rubbish, raised from the ground and the sordid effluents that backwashed the alleyway. The mane of red hair that fell from her head to her waist, her only garment. The sailors who frequented the basement dram-houses of Half Moon Place, had rough-handled her, taken her clothes for sport. But no more.

Ellen hadn’t even resisted. Instead, offered prayers for their wayward souls, which hurried them off.

The glasses she missed more. The alley children had stolen them, fascinated by the purplish hue that helped her eyes. Years in the cordwaining mills of Massachusetts had taken their toll. But she was blessed more than most. Without them she could still see the sun and the stars and the moon. The shoe-stitching she could no longer do. She couldn’t blame Fogarty then, the landlord’s middleman, when eventually he put her out for falling behind with the rent. He wasn’t the worst; had stretched himself as far as one of his kind could.

Even in her current situation, any passer-by would have still considered Ellen O’Malley a striking woman. Firm of countenance, fine of forehead and with remarkable eyes. ‘Speckled emeralds,’ she had once been told, ‘like islands in a lake.’ She smiled at the memory. Tall, she sat unbowed by the circumstances in which she now found herself. Her fortieth year to Heaven behind her, a casual onlooker might have placed Ellen O’Malley at not yet having reached the meridian of life. A flattery from which, once, she would not have demurred.

She had only been out the few nights now and the New England Fall had not been harsh. Biddy Earley, whose voice Ellen heard at night, driving a hard bargain with the men of the sea would, in the daylight hours bring her a cup of buttermilk and a step of bread for dipping in it. Part-proceeds of the previous night. Likewise, Blind Mary, all day on her stoop in nodding talk with herself, would bring her a scrap of this or that, or the offer of a ‘gill of gin’. Then, nod her way homewards again, scattering with her stick the street urchins who taunted her.

Still with her song, Ellen reflected on her state. She was, at last, stripped of everything – a perfection of poverty. No possessions, no desires. Life … and death came and went along the passageways of Half Moon Place with such a frequent regularity that her situation attracted scant attention. Nor did she seek it.

‘Into Thy hands Lord, I commend my Spirit.’

Nothing remained within her own hands, everything in His.

It was a wonderful liberation to at last hand over her life. Not forever seeking to keep the reins tightly gripped on it. Death, when it came, would hold no fears for her. Death was re-unification with the One who created her.

She looked down at her nakedness, unashamed by it, her body now shriven of sin, aglow with the light of Heaven. She had been beautiful once, had fallen from grace, and now, was beautiful again; if less so physically, then spiritually at least.

She thought of her children: Mary, her natural daughter; Louisa, her adopted daughter; Patrick, her son and then, Lavelle, her second husband. How she had betrayed them; her self-exile from their lives; her atonement; and finally, now her redemption.

She had been right all those years ago. To unhinge herself from their lives after her affair … keep them free of scandal. Because of her the girls, postulants then, would likely have been driven from the Convent of St Mary Magdalen. With words like ‘the very reason the vow of purity is so highly prized among the Sisters is that, in its absence, it is humanity’s fatal flaw.’ Ellen considered this a moment … how very true in her own case.

And clothes? Clothes were the outer manifestation of the inner flaw – something with which to cover it up. Down all the centuries since paradise lost. Now, her paradise regained, she had no earthly need of them.

‘I am clothed …’ she sang in her song, ‘… the sun, the moon and the stars – finer raiment than ever fell from the hands of man.’

Then she prayed.

‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph, I give you my heart and my soul;

Jesus, Mary and Joseph, assist me in my last agony;

Jesus, Mary and Joseph, may I breathe forth my soul in peace with you. Amen.’

She followed with the Our Father – in the old tongue Ár n-Athair atá ar Neamh. Then finally, she raised to heaven the long-remembered prayers of childhood.

Afterwards she sang again. The songs she had sung to her own children – nonsensical, infant-dandling songs: aislingi, the beautiful sung vision-poems; and the suantraí, the ‘sleep-songs’ with which she once lullabyed them. Sang to the sun and the teetering tenements of Half Moon Place.

ONE

Convent of St Mary Magdalen, Boston, 1861

‘Half Moon Place …’ Sister Lazarus warned, ‘… is reeking with perils.’ The two younger nuns in her presence looked at each other. Ready for whatever perils the outside world might bring. It was not their first such outing into one of Boston’s less fortunate neighbourhoods. Still, Sister Lazarus considered it her bounden duty, as on every previous occasion, to remind them of the ‘reeking perils’ awaiting them.

‘Now, Sister Mary and Sister Veronica …’ the older woman continued, ‘… you must remain together at all times. Inseparable. The fallen … those women whom you will find there … if they are truly repentant … wanting of God’s grace … wanting to leave …’ She paused. ‘… wanting to leave behind their … previous lives … then you must bring them here to be in His keeping.’

‘Here,’ was the Convent of St Mary Magdalen, patron saint of the fallen of their gender. ‘Here’ the Sisters would care for those women, the leftovers of Boston life. Care for their temporal needs but primarily their spiritual ones.

Sister Lazarus – ‘Rise-from-the-Dead’ as the two younger nuns referred to her – reminded them again that their sacred mission in life was to ‘reclaim the thoughtless and melt the hardened’.

The older nun took in her two charges, still in their early twenties. Sister Mary, tall, serene as the Mother of God for whom she had been named. Blessed with uncommon natural beauty. Most of it now hidden, along with her gold-red tresses, under the winged, white headdress of the Magdalens. And not a semblance of pride in her beauty, Sister Lazarus thought. Oh, what novenas Sister Lazarus would have offered to have been blessed with Sister Mary’s eyes – those sparkling, jade-coloured eyes, ever modestly cast downwards – instead of the slate-coloured ones the Lord had seen fit to bless her with. The older nun corrected her indecorousness of thought. Envy was a terrible sin. She turned her attention to the other young nun before her.

Sister Veronica’s eyes were entirely a different matter.

Sister Veronica did not at all keep her attractive, hazel-brown eyes averted from the world, or anybody in it – including Sister Lazarus. Nor was Sister Veronica at all as demure in her general carriage as Sister Lazarus would have liked. Instead, carried herself with a disconcerting sweep of her long white Magdalen habit. Which always to Sister Lazarus, seemed to be trying to catch up with the younger nun. Unsuccessfully at that!

‘Impetuosity, Sister Veronica,’ the older nun had frequently admonished, ‘will be your undoing. You must guard against it!’

She saw them out the door, a smile momentarily relieving her face. If the hardened were indeed to be melted, these two were, for all such ‘meltings’, abundantly graced. Though Sister Lazarus would never tell them so. Praise, even if deserved, should always be generously reserved.

Praise could lead to pride.

‘There are so many fallen from God’s grace, Louisa,’ Sister Mary said when once out of earshot of the convent. She used the other nun’s former name, the one she had known her adopted sister by for more than a dozen years. Since first they had come out of Ireland.

‘God takes care of His own,’ Louisa replied.

‘And Mother?’ Mary asked, the question always on her mind.

Louisa took her sister’s arm.

‘Yes … and Mother too,’ Louisa answered. ‘We would surely have heard. Somebody would have brought news if something had happened’.

But something had happened.

Life had been good once. Their mother had made their way well in America, educating both herself and them. She had re-married – Lavelle – built up a small if successful business with him. Then it had seemed to all go wrong, the business failing. When a move from their home at 29 Pleasant Street to more straitened accommodation had been imminent, Mary and Louisa had both secretly decided to unburden the family of themselves. To follow the nudging, niggling voice they had been hearing.

‘It almost broke poor Mother’s heart,’ Mary said.

‘Then, do you remember, Louisa, once in the convent, everything silent – just like you?’

Louisa nodded, remembering. As a child she had been cast to the roads of a famine-ridden Ireland, her parents desperate in the hope she would fall on common charity and survive the black years of the blight. Six months later Louisa had returned to find them, huddled together; their bodies half eaten by dogs, likewise famished. She had gone silent then. All sound, it seemed, trapped beneath the bones that formed her chest. Nor did she retain a memory of any name they had called her by – not even their own names.

A year later Ellen had found her, taken her in. Though some early semblance of speech had returned in the intervening year, her silence had helped Louisa survive. Drawn forth whatever crumbs of charity a famished people could grant. So she had remained silent. Kept her secret. Afraid, lest once revealed, all kindness be cut off and she condemned, like the rest to claw at each other for survival. She had remained ‘the silent girl’ until they reached America and Ellen had christened her. After the place in which they had found her – Louisburgh, County Mayo – and the place to which they were then bound for, Boston, with its other Louisburgh … Square.

Gradually the trapped place beneath Louisa’s breast had freed itself. Then, in the safe sanctum of the cathedral at Franklin Street she had whispered out halting prayers of thanksgiving.

At the edge of Boston Common, they stood back to let a group of blue-clad militia double-quick by them. The young men all a-gawk at the wide-winged headdresses of the two nuns.

‘Angels from Heaven!’ a saucy Irish voice shouted.

‘Devils from Hell!’ another one piped.

Then they were gone, shuffling in their out-of-time fashion to be mustered for some battlefield in Virginia.

‘I pray God that this war between the States will be quickly done with,’ Mary said quietly.

‘Do you remember anything, Mary – anything at all?’ Louisa asked, returning to the topic that, like her sister, always occupied her mind.

‘Nothing … only, like you, that Mother had once called to the convent, leaving no message … and then those messages left by Lavelle and dear brother Patrick that they had not found her. I cannot imagine what … unless some fatal misfortune has … and I cannot bear to think that.’

Louisa’s mind went back over the times she and her adoptive mother had been alone. That time in the cathedral at Holy Cross when Ellen had tried to get her to speak. How troubled her mother had seemed. And the book, the one which Ellen had left on the piano. Louisa had opened it. Love Elegies … the sinful poetry of a stained English cleric – John Donne. It had shocked Louisa that her mother could read such things – and well-read the book had been.

‘Did you ever see a particular book – Love Elegies – with Mother?’ she asked Mary.

Mary thought for a moment.

‘No, I cannot say so, but then Mother was always reading. Why …?’

‘Oh, I don’t know, Mary, something … a nun’s intuition.’ Louisa laughed it off. Then, more brightly, gazing into her sister’s face, ‘You are so like her … so beautiful … her green-speckled eyes, her fiery hair …’

‘That’s if you could see it!’ Mary interjected.

‘Personally cropped by the stern shears of Sister Lazarus,’ she added. ‘That little furrow under Mother’s nose – you have it too!’

Louisa went to touch her sister’s face.

‘Oh, stop it, Louisa!’ Mary gently chided. ‘You are not behaving with the required decorum. If “Rise-from-the-Dead” could only see you!’

Louisa restrained herself. ‘I am sorry … you are right,’ she said, offering up a silent prayer for unbecoming conduct – and that the all-seeing eye of Sister Lazarus might not somehow be watching.

‘We are almost there,’ was all Mary answered with.

Half Moon Place held all the backwash of Boston life. As far removed from the counting houses of Hub City as was Heaven from Hell. It housed, in ramshackle rookeries, the furthest fringes of Boston society – indolent Irish, fly-by-nights and runaway slaves. None of which recoiled the two nuns. Nor the reeking stench that, long prior to entering them, announced such places. Since Sister Lazarus had first deemed them ‘morally sufficient’ for such undertakings, many the day had the older nun sent them forth on similar missions of rescue. Them returning always from places like this with some unfortunate in tow, to the Magdalen’s sheltering walls.

This was their work, their calling. To snatch from the jaws of iniquity young women who, by default or design, had strayed into them.

‘Reclaim the thoughtless and melt the hardened.’ Sister Lazarus’s words seemed to ring from the very portals of what lay facing them today. Half Moon Place indeed would be a fertile ground for redemption.

‘A Tower of Babel,’ Louisa said, stepping precariously under its archway into a rabble of tattered urchins who chased after some rotting evil.

‘Kick the Reb! Kill the Reb!’ they shouted, knocking into them with impunity.

A nodding woman, on her stoop, shook her stick after them.

‘I’ll scatter ye … ye little bastards! God blast ye! D’annoyin’ the head of a person, from sun-up to sundown!’

From a basement came the dull sound of a clanging pot colliding with a human skull. A screech of pain … a curse … it all just melting into the sounds that underlay the stench and woebegone sight of the place.

Further along, a woman singing. The snatches of sound attracted them. ‘The soul pining for God,’ Mary said, as the woman’s keening rose on the vapours of Half Moon Place … and was carried to meet them. They rounded the half-moon curve of the alleyway. The singing woman sat amidst a pile of rubbish as if, herself, discarded from life. The long tarnished hair draped over her shoulders her only modesty. But her face was raised to a place far above the teetering tenements, and her song transcended the wretchedness of her state.

‘If not in life we’ll be as one

Then, in death we’ll be,

And there will grow two hawthorn trees

Above my love and me,

And they will reach up to the sky –

Intertwined be …

And the hawthorn flower will bloom where lie

My fair-haired boy … and me.’

It was Louisa who reached her first, hemline abandoned, wildly careering the putrid corridor. Mary then, at her heels, the two of them scrabbling over the off-scourings and excrement. Then, in the miracle of Half Moon Place, breathless with hope, they reached her. As one, they clutched her to themselves.

Praising God. Cradling her nakedness. Wiping the grime and the lost years from her face.

‘Mother!’ they cried. ‘Oh, Mother!’

TWO

They huddled about her, calling out her name, their own names. Begging for her recognition.

‘Mother! Mother! It’s us … Mary and Louisa,’ Mary said, stroking her mother’s head. ‘You’ll be all right now. We’ll take you back with us.’

‘Mary? Louisa? It’s …’ Ellen began.

‘Her mind is altered,’ a voice rang out, interrupting. ‘Too much prayin’ and Blind Mary’s juniper juice,’ the voice continued.

‘We are her daughters,’ Mary said, turning to face the hard voice of Biddy Earley.

‘Daughters – ha!’ the woman laughed. ‘Well blow me down with a Bishop’s fart,’ she said, arms akimbo, calloused elbows visible under her rolled-up sleeves. ‘Oh, she was a close one, was our Ellie. Daughters? An’ us fooled into thinking she had neither chick nor child.’

‘What happened to her?’ Louisa asked.

‘The needle blindness … couldn’t do the stitchin’ no more. But she’s not as bad as she makes out … can see when she wants to!’ the woman answered disparagingly. ‘Fogarty, the landlord’s man, tumbled her out. Just like back home, ’ceptin’ now it’s your honest-to-God, Irish landlords here in America, ’stead of the relics of auld English decency. ’Twould put a longing on a person for the bad old days!’

Ellen, struggling to take it all in, again made to say something.

‘Sshh now, Mother,’ Louisa comforted. ‘Talk is for later. We have to get you inside,’ she said, looking at Biddy Earley.

Reluctantly, Biddy agreed, cautioning that the ‘widow-woman brought all the troubles on herself.’

Mary and Louisa, shepherding Ellen, followed Biddy down into the dank basement where the woman lived.

‘I’ve no clothes for her, mind – ’ceptin’ what’s on me own back,’ she called to them over her shoulder.

Mary would stay with Ellen, Louisa would make the journey back to the convent to get clothes. The Sisters, providential in every respect, always kept some plain homespun, diligently darned against a rainy day – or a novice leaving.

Mary then removed her own undergarment – long white pantaloons tied with a plain-ribboned bow at the ankle. These she pulled onto her mother. Similarly, and aware of the other woman’s stare, she removed as modestly as she could, the petticoat from under her habit, fastening it around Ellen. Biddy, for all her talk about ‘no clothes’, produced a shawl, even if it was threadbare.

‘Throw that over her a while,’ she ordered Mary.

Ellen again started to say something, prompting the woman to come to her and shake her vigorously.

‘Just look at you – full of gibberish … same as ever!’ she said roughly. ‘This is your own flesh and blood come for you, widow-woman! Will you whisht that jabberin’!’

To Mary’s amazement, Biddy Earley then drew back her hand and slapped Ellen full across the face.

‘You wasn’t so backward when you was accusatin’ me o’ stealin’ your book,’ she levelled at Ellen.