Полная версия

Paper: An Elegy

Antonio split the spines of books, spilling leaves of Austen and Cervantes, sheets from Leviticus and Judges, all mixing with the pages of The Book of Incandescent Light. Then Antonio unrolled the wrapping paper and construction paper and began to cut at the cardboard and then fold.

She was the first to be created: cardboard legs, cellophane appendix, and paper breasts. Created not from the rib of a man but from paper scraps.

This magnificent creature rises from Antonio’s cutting table, steps over her exhausted, dying creator, and strides out into the world.

Let us take her hand now and enter the Paper Museum.

A Note on the Paper Used in the Writing of this Book

All my books have really been counterproofs, or offsets, re-marques, like cartoons, those drawings made to the same scale as the grand painting or fresco but which are in fact only preparatory, and which are applied to the wall, and pricked through or indented: a mere outline or image of some greater design.

This book I like to think of not as a cartoon but as like John F. Peto’s ‘Old Scraps’ (1894), a miniature trompe l’oeil. Or a trompe l’esprit.

‘I am typing this book on yellow paper,’ announces the narrator of Stevie Smith’s Novel on Yellow Paper (1936). ‘It is very yellow paper, and it is this very yellow paper because often sometimes I am typing it in my room at my office, and the paper I use for Sir Phoebus’s letters is blue paper with his name across the corner.’ The yellow paper helps distinguish the novel from the work.

Alas, I have adopted no such sensible system.

I have typed on a laptop, and on a desktop. I have read many books: paper books, Kindle books, Google books. I have read articles online, in print journals, and in magazines. I have made copies; I have pressed ‘Print’. I have written notes in margins, and I have written notes, by hand, in notebooks, and on A4 narrow-feint paper. I have organised my notes into folders. I have disorganised my notes in the folders. I have typed sentences, then paragraphs, then chapters. I have printed out these chapters, marked up revisions and corrections in pencil, and then incorporated these changes, and printed out the chapters again. And again. And again. And again. And then finally, I sent the ‘document’ by email to my editor, who suggested further changes. Some of which I ignored. Most of which I ignored. But some of which I incorporated. And all of which required yet more printing, and marking up and correcting, before sending it all off again. And then again. Proofs. More corrections. More proofs. Interminable? Inexplicable.

In total, this book is made from twenty reams of plain white 80 gsm copier paper, fifteen A4 lined, narrow-feint pads, four Moleskine pocket notebooks, six packs of A5 lined index cards, fifty manila folders (green), and three wrist-thick blocks of Post-it notes (assorted colours). I’m sure there are easier ways of writing books.

Too much? Too much. Not enough.

Japanese tissue paper with fine swirls of fibre

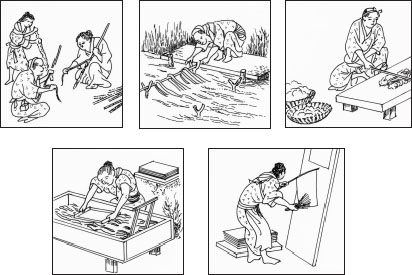

Making Japanese paper:

1 Stripping the bark

2 Soaking the bark in water

3 Beating the fibres to a pulp

4 Placing the paper mould into the vat of pulp

5 Drying and polishing the resulting sheet of paper

You are living, let us say, in Japan, two thousand years ago. You and your family have planted some trees – mulberry trees. The trees grow. You remove some of the branches of the trees and steam them in order to loosen the inner bark. You peel and dry and soak and scrape and rinse the bark. You find this pleasing: it turns the bark whiter and lighter. The fibres of the bark begin to separate. You boil the bark to soften it further, and then you bleach it in the sun. And then you beat it, and you beat it, and you beat it with a wooden beater and then you throw lumps of this bleached bark pulp into a vat filled with water. And then you mix it and beat it again. And again. You now have a vat of grey mush. You take a wooden frame with a sieve-like screen, dip it into the mush, scoop up the frame, tossing off the excess water, and rock it back and forth until you have a nice, smooth, consistent sheet of mush on your sieve. You allow all the water to drain off. Now you have a sort of damp mat of macerated fibre stuck to your sieve. You remove this mat from the sieve, and place it on a wooden board to dry. It dries, and you smooth it and polish it, maybe with some animal fat or maybe just with a stone, anything you can get your hands on to make it shiny and smooth. And then you trim the edges and admire your handiwork. Congratulations. You have produced a sheet of paper.

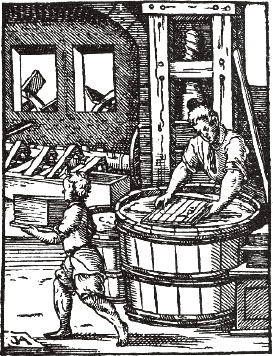

Basically, paper has continued to be made by this method throughout the world to this very day, and seems likely to continue to be made by the same method tomorrow. Compare the ancient Japanese technique to John Evelyn’s description of hand paper-making in seventeenth-century England, for example, from his diary, dated 24 August 1678:

I went to see my Lord of St. Alban’s house, at Byfleet, an old large building. Thence, to the paper-mills, where I found them making a coarse white paper. They cull the rags which are linen for white paper, woollen for brown; then they stamp them in troughs to a pap, with pestles, or hammers, like the powder-mills, then put it into a vessel of water, in which they dip a frame closely wired with wire as small as a hair and as close as a weaver’s reed; on this they take up the pap, the superfluous water draining through the wire; this they dexterously turning, shake out like a pancake on a smooth board between two pieces of flannel, then press it between a great press, the flannel sucking out the moisture; then, taking it out, they ply and dry it on strings, as they dry linen in the laundry; then dip it in alum-water, lastly, polish and make it up in quires. They put some gum in the water in which they macerate the rags. The mark we find on the sheets is formed in the wire.

The details may differ, but the processes remain essentially the same (as indeed did Evelyn’s famous note-taking habit, established at the age of just eleven, and which sustained him over seventy years, through Oxford, a Grand Tour, the English Civil War, Cromwell’s Protectorate, the Restoration, and work on dozens of books and treatises).

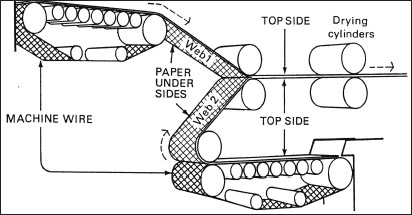

Industrial methods have now largely replaced hand-beating and dipping and drying, with mechanical agitators to beat pulp, and high-pressure jets and conveyor belts to spray it and spread it, and vacuums and cylinders and presses to dry it, and rollers to polish it, but there are still really only three stages in the whole paper-production process: the preparing of the pulp; the forming of the paper on a mould or a mesh; and the drying and finishing. In a modern paper plant, these stages translate into a process that goes something like this. Bales of wood pulp are fed into a hydrapulper, in which the pulp is diluted with water and mixed – think of a hydrapulper as a giant Moulinex, and the pulp as paper-gruel. The porridge-like substance produced – the ‘stock’ or ‘stuff’ – can then be further diluted and undergo further beating, or fibrillation, to cut and break up the fibres of the pulp, and screened to remove impurities, and blended with various additives. Then, and only then, is the stuff ready for the papermaking machine proper. A typical modern machine is mind-bogglingly huge: hundreds of metres long, costing millions, running twenty-four hours a day and capable of producing hundreds of thousands of tonnes of paper every year. The slurry, or stock – which looks like milk at this stage, or at least a kind of thin white water – passes through a ‘flow box’ or ‘head box’, where it is sprayed onto a mesh conveyor belt. As the stock is sprayed, the water drains through the mesh, leaving behind a fibrous mat, just as in the early Japanese hand moulds, only on a massive scale, and at astonishing speed. The stuff then passes through heavy rollers, with more moisture being squeezed and sucked out, and beneath a dandy roll, and through steam-heated drying cylinders and a size press, where sizing is added – the starch that reduces absorbency – and then over the calender, the big iron rollers which polish and glaze the surface of the paper, and finally it passes onto large reels, ready to be cut into sheets or split into smaller reels and packed for despatch to paper merchants and converters who will produce and package the paper ready for you to print out your essential emails and flight boarding details.

Papermaking: the same yesterday, today and tomorrow

A diagram of a papermaking machine

It is an amazing sight to see a modern paper machine in full flow, even now in the twenty-first century: in the nineteenth century it was nothing less than astonishing. Herman Melville, that great nineteenth-century chronicler of astonishment, describes a paper mill in his story ‘The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids’ (1855), in which the narrator visits a mill which is oddly but reassuringly very like a whale, a ‘large whitewashed factory’, ‘like an arrested avalanche’. This vast white beast, which swallows up rags and water and people, is located ‘not far from Woedolor Mountain in New England … By the country people … called the Devil’s Dungeon’. The narrator of the story is a businessman, ‘Having embarked on a large scale in the seedsman’s business’, who is seeking a cheap wholesale source for seed packets. Inside the factory he stands, amazed:

Something of awe now stole over me, as I gazed upon this inflexible iron animal. Always, more or less, machinery of this ponderous, elaborate sort strikes, in some moods, strange dread into the human heart, as some living, panting Behemoth might. But what made the thing I saw so specially terrible to me was the metallic necessity, the unbudging fatality which governed it. Though, here and there, I could not follow the thin, gauzy veil of pulp in the course of its more mysterious or entirely invisible advance, yet it was indubitable that, at those points where it eluded me, it still marched on in unvarying docility to the autocratic cunning of the machine. A fascination fastened on me. I stood spellbound and wandering in my soul. Before my eyes – there, passing in slow procession along the wheeling cylinders, I seemed to see, glued to the pallid incipience of the pulp, the yet more pallid faces of all the pallid girls I had eyed that heavy day. Slowly, mournfully, beseechingly, yet unresistingly, they gleamed along, their agony dimly outlined on the imperfect paper, like the print of the tormented face on the handkerchief of Saint Veronica.

Who could possibly have conceived of such a monster, such a panting Behemoth? A man called Louis-Nicolas Robert could. Like Melville, Robert too saw the pallid faces of the workers in the pallid incipience of the pulp, though where Melville saw agony and torment, Robert saw freedom and liberation. In its very incarnation, by its very originators, the papermaking machine was seen as a metallic necessity, a triumph of technology over man.

Louis-Nicolas Robert, born in Paris in 1761 and nicknamed ‘the Philosopher’ at school, became a soldier in the French army, in the First Battalion of the Grenoble Artillery. Restless and dissatisfied, and with no prospect of promotion, he eventually found himself back in Paris in the very midst of the French Revolution, working as ‘an inspector of personnel’, a classic petit cadre, in a paper mill at Essonnes, to the south of Paris, where he was appalled by the behaviour of the workers, who had become infected with the ideas of the times. Encouraged by his employer, François Didot, Robert began experimenting with plans for a machine that could replace the troublesome papermakers. After much trial and error just such a machine was devised, and on 18 January 1799 Robert was granted a patent for a papermaking machine to make ‘sheets of an extraordinary length without the help of any worker’. Ironically, Robert and Didot then began wrangling between themselves, arguing about money and the patent, but since neither man could afford to make a success of the enterprise alone, Didot called upon his brother-in-law John Gamble, an Englishman, who took drawings and samples of the machine-made paper to London in 1801, hoping to find investors. Gamble got lucky: he managed to persuade a famous, wealthy family of London stationers, the Fourdriniers, to back him, and together they were soon granted an English patent for an ‘Invention for Making Paper’ (‘in single sheets, without seam or joining, from one to twelve feet and upwards wide and from one to forty feet and upwards in length’). The industrial history of papermaking had begun.

Robert’s machine was brought from France in 1802, and the Fourdriniers employed a young man called Bryan Donkin to modify and improve it. Like Robert a genius in the pay of the boss class, Donkin became a kind of consultant inventor who worked out of a factory set up for him by the Fourdriniers in Bermondsey, where he established the first British cannery, was responsible for developing split steel nibs for pens, designed and improved metalworking tools such as lathes and drills, and ended up advising Marc Isambard Brunel in his work on the Thames Tunnel. But the paper machine was his first big break. He set about making a series of improvements to Robert’s prototype, removing the vat from below the wire and eventually replacing the hand-operated crankshaft with a mechanical drive. The first improved Fourdrinier machine was set up at Frogmore Mill in Hertfordshire in 1803, and remains the effective template for all modern paper machines: a moving belt made of wire mesh has stock poured onto it, water drains through the mesh, leaving a fibrous sheet, which is cut into sections and hung out to dry, as indeed were the Fourdriniers, who had poured money into the enterprise and found themselves bankrupt by 1810, having made a net loss on the machine of over £50,000, though years later Parliament granted them some small compensation for ‘being reduced to comparative poverty in the evening of a long life spent in the execution of a great national object’.

The great national object did not meet, however, with universal acclaim. As it was for the mighty Fourdriniers, so it was for the lowly workers, only more so: the machines stole not their capital but their livelihoods. More and better machines meant that fewer and less-skilled people needed to be employed. The machine became an enemy. During the Swing riots that spread throughout England in 1830 a number of paper mills were attacked – in Norfolk, Wiltshire, Worcestershire and Buckinghamshire. Most of those involved seem to have been members of the Original Society of Papermakers, who were furious and fearful for their futures. But, alas, the riots solved nothing. Several paper manufacturers went out of business, and those workers who were tried and found guilty were transported to Tasmania. The march of the machines continued.

Progress was relentless. The cylinder machine – using a revolving brass cylinder that was part submerged in the pulp vat – had been patented by another Englishman, John Dickinson, in 1809, and on 29 November 1814 The Times became the first newspaper printed on such a machine. In 1820 Thomas Bonsor Crompton was granted a patent for drying cylinders, which meant paper no longer had to be hung to dry. In 1824 John Dickinson was granted another patent – he was, with Bryan Donkin, one of the great paper pioneers – this time for a machine that pasted paper together to form a kind of cardboard. In 1825 the first ‘dandy roll’ was developed, so-called because on seeing it in action workers at the mills apparently exclaimed ‘What a dandy!’ It was used to press watermarks into machine-made paper. A Fourdrinier machine – built by Donkin in England – was set up in America in 1827. In 1830 bleach was introduced into the process of turning rags into paper. In 1840 Friedrich Gottlob Keller, a weaver and reed-binder in Saxony, patented a wood-grinding machine, making mass paper production possible. Christmas cards, photographs, adhesive postage stamps and paper bags all began to be produced during the 1840s and 1850s, and by 1900 there were machine-made cigarette papers, tracing papers, cups, plates, collars, cuffs, napkins, tissues and almost every other imaginable paper product. With the first commercial production of corrugated cardboard boxes around the turn of the century – making it possible for paper safely to send itself to itself by itself – the Age of Paper had reached its zenith.

Watermarks: the equivalent of an artisan’s trade-mark

It all began in China, of course, many years ago, and it continues in China still, where the political, economic and cultural significance of paper can’t be overestimated: traditional prayers are still written on paper and burned; traditional paper kites are still flown; and traditional cut paper is still used to decorate shrines. More importantly, the Chinese paper industry is now booming and grinding in the same way it boomed in Europe and America in the nineteenth century, with a consolidation of production into large-scale mills and a move away from the use of recycled material towards the use of wood pulp (largely imported from Russia) to feed the country’s burgeoning appetite for brand spanking new Western-style packaged consumer goods, mail-order catalogues, newspapers, magazines and paper money. It’s possible, as some scholars have suggested, that paper was not originally a Chinese invention, and that the Khanzadas people, from Tizara in the Alwar district of Rajasthan in India, first made it from cellulose fibres sometime in the third century BC. Or maybe the Aztecs. Or the Mayans. It’s also possible that the Chinese did not invent printing, gunpowder and the compass. But even if they didn’t invent them, they may as well have done: they did invent banknotes, and cannonballs, and manned flight with kites, and numerous astronomical instruments; whether or not they got there first with the four great inventions, they were certainly early adopters. In August 2006 at Dunhuang, in the Gansu province of north-western China, an important town on the ancient Silk Road and the site of numerous archaeological discoveries over the past hundred years, flax paper was discovered that dates back to the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC– 220 AD), meaning that paper may have been in use at least two hundred years before the oft-cited date of 105 AD, when T’sai Lun, the Shang Fang Si, the officer in charge of the Emperor’s weapons and instruments, is said to have first reported its invention.

From Dunhuang it is possible to chart the vast westward drift of paper, like a slow-moving landslide. Plotted by significant sites of paper production, and going from right to left, the paper trail flows majestically over about a five-hundred-year period, first from China to Samarkand, and then to north Africa (Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, Fes), before moving on to Europe between the tenth and twelfth centuries (Xativa, Fabriano, Troyes, Nuremberg, Krakow, Moscow). By the fifteenth century pulp tech had even washed up in England: John Tate established the first paper mill in Britain, in Hertfordshire, in 1495. Legend has it – a legend derived from an old Arabic manuscript, Roots of Trades and Kingdoms – that papermaking began its long journey to the west at a battle in AD 751 at the River Talas (Tharaz/Taraz), about five hundred miles east of Samarkand, at which Arab armies, victorious over the Chinese, seized some papermakers as prisoners, who promised to reveal the secrets of papermaking in exchange for their freedom.

True or not, by the end of the eighth century the Sogdian Arabs had certainly taken to papermaking, and paper had taken to them: they had become, like us, paper people. The first paper factory opened in Baghdad in 793–94, and under the Abbasid caliphate, the great Islamic Golden Age, the city became a centre of learning with its own unique paper market, consisting of shops and stalls, fueling and fulfilling the great demand for paper by the city’s artists, philosophers and scientists. By the ninth century paper was being produced in Damascus, in Hama, and in Tripoli, and by the end of the tenth century the skills and knowledge of papermaking, carried by Muslim scribes and texts, had spread through Tunisia, Mauritania and Morocco, arriving in Spain around 950 AD. The production and manufacture of paper, if not its actual invention, might therefore be said to be one of Islam’s many gifts to the West (the word ‘ream’, as the great scholar of Islamic papermaking, Jonathan Bloom, points out, derives from the Arabic word for ‘bundle’). Though it was not a gift that was always warmly received, even by the most foresighted and discerning: in 1221 the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, bald and brilliant, known as the stupor mundi, the wonder of the world, issued a decree declaring that all documents written on paper were invalid; they would not last; they were ephemeral. Some scholars have speculated that the stupor mundi may have been under pressure from sheep and cattle breeders who were fearful of losing the market for parchment. Or maybe Frederick was just not so stupor after all. Either way, the decree came too late: paper was the future. Parchment was yesterday’s news.

So from China to the Arab world, and through the Byzantine Empire into Christian Europe, paper made its slow procession – and slow precisely because hand papermaking was a slow process. It was also cold, hard work: for the vatman, who dipped the mould into the vat, and lifted it out, allowing the water to drain; for the coucher, who removed the wet sheet from the mould and laid it on felt; and for the layman, who stacked and pressed the sheets and hung them to dry, sheet after sheet after endless weary sheet. And this is not to mention all the other equally backbreaking and even less glamorous tasks: before the invention by the Dutch of the so-called Hollander beater in the early eighteenth century there was the shredding and beating of the rags for the pulp; and the dipping of the finished sheets in sizing; and the polishing of the pages by hand, or calendering them between rollers; the eternal smoothing out of ridges and wrinkles. Dard Hunter, who knew papermaking from the inside out, and the outside in – as both a scholar and a practitioner of the craft, and as the founder of his own paper mill, and a paper museum, and the author of one-man books, The Etching of Figures (1916) and The Etching of Contemporary Life (1917), for which he made the paper, and designed and cut and cast the typeface, and etched the pictures and wrote the words – believed that papermakers needed unusually robust constitutions because ‘the constant stooping posture, combined with the heat of the paper stock in the vat, caused them to grow old prematurely … at fifty many of these hard-working craftsmen appeared to have reached the allotted threescore years and ten’.

And yet despite all these hardships, traditions of hand papermaking still survive. Gandhi famously demonstrated papermaking at the 1938 Haripura Congress, and ancient methods of Indian papermaking are still maintained in a town called Sanganer, near Jaipur, where all the paper is chemical-free, sun-dried, unbleached and naturally coloured. In Nepal, hand-made lotka paper is still made from the bark of daphne trees. And in Japan there will always be washi. ‘Why is washi so wholesome?’ asks Soetsu Yanagi, co-founder of the Japan Folk Art Society. ‘When we try to figure it out, we cannot help but think it is because nature is paper’s mother and tradition paper’s father.’ And England? In England, the Exotic Paper Company of Chilcompton, Somerset, makes a paper using elephant dung from Woburn Safari Park.