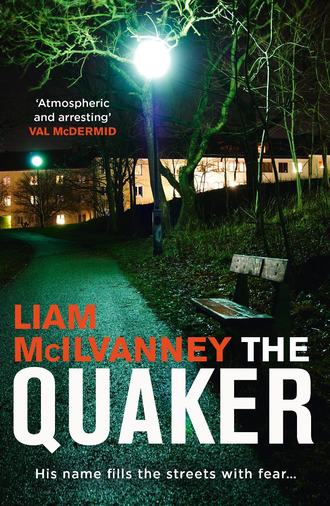

The Quaker

Полная версия

The Quaker

Жанр: детективыисторическая литературасовременная зарубежная литератураполицейские детективысерьезное чтениеоб истории серьезно

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу